Media | Articles

Chrysler’s ill-fated Turbine program went way beyond the iconic Ghia car

At the dawn of a new era, when space travel was becoming a possibility and jet-age automotive styling was all the rage, Chrysler engineers began to explore turbine power as an alternative to piston engines. It was the beginning of a 30-year deep dive that resulted in the iconic 1963 Chrysler Turbine—and so much more.

Beginning in 1953 and continuing into the early 1980s, Chrysler was relentless in its pursuit of a turbine-powered car that was both fuel-efficient and on-budget. It fell short, obviously, but the massive effort wasn’t for naught. Lessons were learned and legends were made. Like the Ghia-bodied Turbine car that became the public face of the program.

Last week, one of only nine surviving examples (chassis #99123)—one of two in public hands—was sold through Hyman Ltd., snatched up after lingering on the market for all of 72 hours. The sale price was not revealed, but it was easily into the seven figures. Even then, the money was well spent.

“It’s the ultimate dream car for a museum or an event or an individual, because it made such a dramatic impact on automotive history, and you’ll have to wait a very long time for another chance to own one,” says Dave Kinney, publisher of the Hagerty Price Guide. “There’s no such thing as paying too much for something if it’s the object of your desire. And, in terms of investment, it will continue to grow in value, much like rare metals.

“When an appraiser is asked to value a car that’s one of a kind or one of a very few, you’re looking for specific things to compare it to. Mechanical innovation would be on the list … and attractive jet-age styling, rarity, and the impact it made when it was new. Obviously, this one is off the charts in all those areas … And when you start looking for comparisons, where do you look? A steam-powered car? A rocket car? A B.A.T. car? It’s pretty difficult—maybe even impossible.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Consigner Mark Hyman refused to reveal the price of the car or the identity of the buyer, but he says ownership “won’t be a secret for long. I can tell you it’s going to a museum, and I wouldn’t want to steal any thunder from their announcement.”

The fact that the Turbine car sold so quickly was not surprising. “This is one of the most significant post-war automobiles ever built,” Hyman says. “It’s a really nice original car. The paint is nice, the interior is immaculate, and it runs and drives well. It’s just a really nice car.

“I knew who the potential buyers were; I just didn’t know which one would be willing to buy it at this time and at this price,” Hyman adds. “I’m happy it isn’t going behind closed doors, never to be seen in public again. It’s going to a really good home. They’ll give it the importance and attention it deserves, and people in the U.S. will be able to see it and appreciate it.”

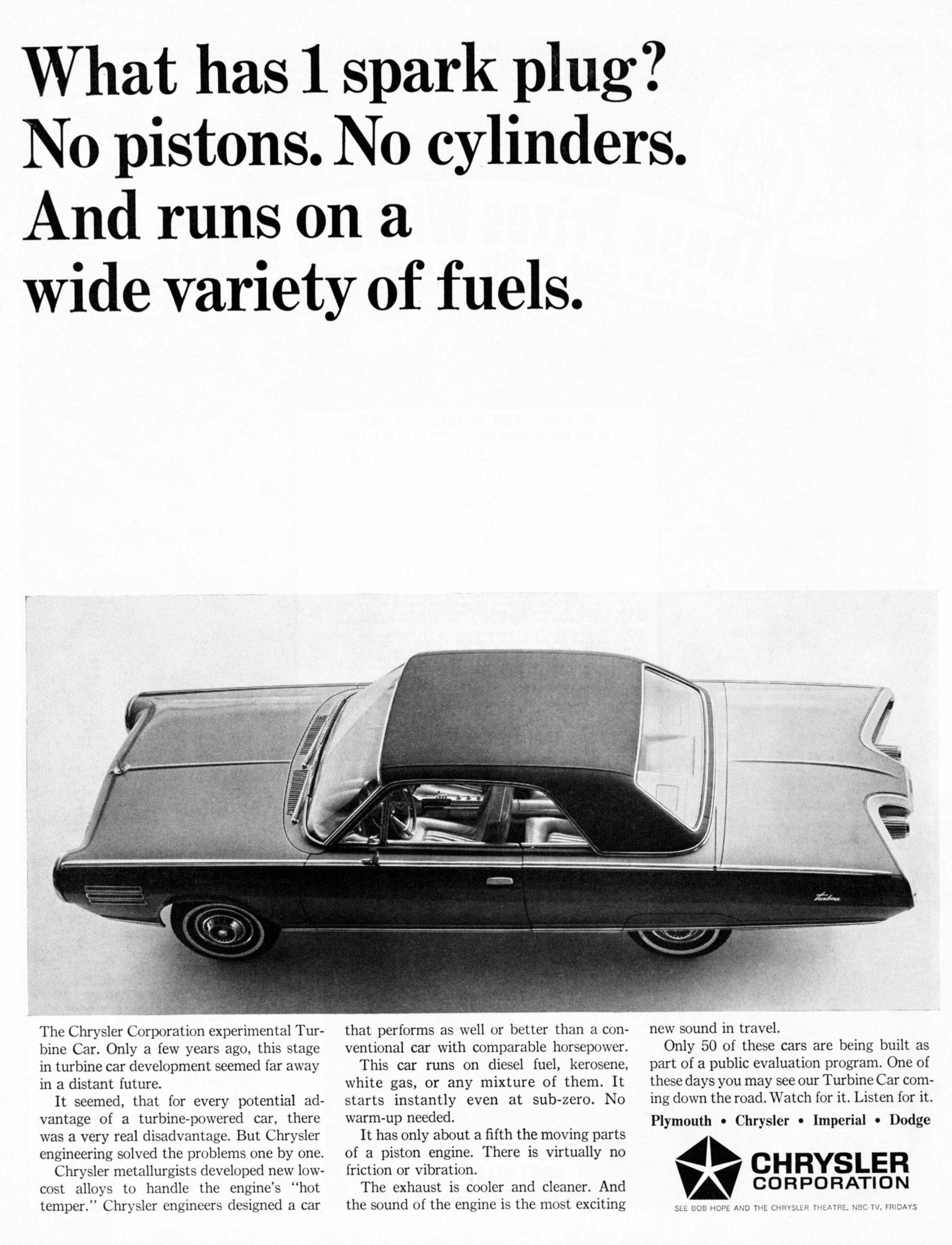

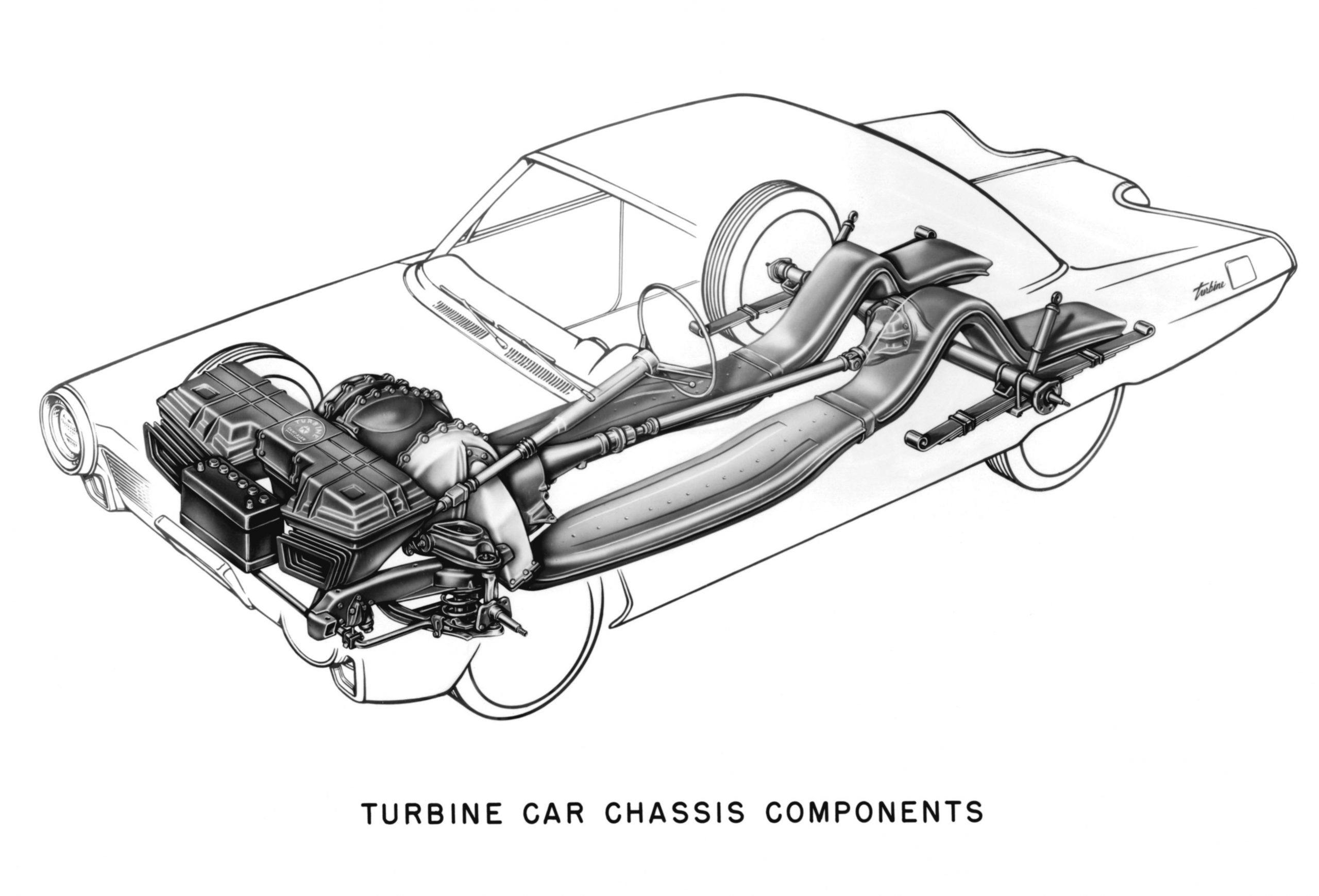

Chrysler’s connection to turbine power began during World War II, when its engineers worked to create a turboprop engine for the U.S. military. In 1953, eight years after the war ended, Chrysler turned its attention to developing the gas turbine engine for automobiles. The engine’s incredible soundtrack aside, a turbine offers many advantages: relative simplicity (roughly half the parts of a piston engine), less wear (no reciprocating components), exceptional power-to-weight ratio, less engine vibration, and near-silent operation. Plus, it can run on basically any combustible liquid—including kerosene, peanut oil, even tequila (but not leaded fuel, as it leaves mineral deposits on the components). The turbine has its share of drawbacks, however: a lack of engine braking, high fuel consumption, high heat, and acceleration lag.

It was up to Chrysler to accentuate the positive and diminish the negative.

Chrysler’s first turbine-powered car was a 1954 Plymouth, followed by a turbine ’56 Plymouth that successfully completed a 3020-mile cross-country road test. That experience fueled a new generation of turbine engine that was more powerful, compact, and efficient than ever before. Still, most people didn’t notice Chrysler’s efforts until 1963, when the company rolled out its most recognizable version.

Styling was done in-house, overseen by the new design chief Elwood Engel, but Chrysler contracted with Ghia in Turin, Italy, to build the bodies. Shipped to Michigan and mated to a bespoke chassis, 55 Chrysler Turbines were built. The first five “prototypes” varied in color and trim, but a fleet of 50 followed, wearing identical metallic bronze paint, black vinyl roof, and bronze interior.

To gauge feasibility and generate publicity, Chrysler loaned “the famous 50” to private individuals around the country, and from 1963–66 a total of 203 people drove a Turbine car for three months and evaluated its performance. The results were promising. The cost of building the cars, however, was not.

“A mid-range vehicle in the 1960s cost about $3000, and the turbine engine alone cost $10,000 or more to manufacture,” says Brandt Rosenbusch, manager of historical services for Stellantis North America (parent company of Chrysler). “It just made no sense. To ramp up an entire plant to build 100,000 a year wasn’t realistic.”

When the loan program ended, the cars were returned to Chrysler, which kept three. Six more were deactivated and given to museums—delivered with a crated turbine engine and transmission for display. The rest were sent to a Detroit scrapyard and destroyed.

Rosenbusch, who manages Chrysler’s corporate archives and its collection of 365 historic vehicles (including some AMC products), says that although it is difficult to watch the Turbine cars being destroyed, the reasoning behind the decision is understandable.

“Like every other auto company, Chrysler didn’t want prototypes out on the road,” he says. “They were famous cars; they had their life. We didn’t want them to end up on a used car lot or have somebody pull out the turbine engine and put a 318 in one or a Hemi in one—and people would. So, while it’s a horrific video for anyone who cares about automotive history, the process was definitely justified.”

Rosenbusch says Chrysler still owns two of the Turbines; the third was sold to Jay Leno after the Walter P. Chrysler Museum closed about a decade ago. The other six were given to the Detroit Historical Museum, The Smithsonian Institution, The Henry Ford, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles (now the Petersen Automotive Museum), the Museum of Transportation near St. Louis, and the Harrah Collection Museum in Reno, Nevada. At the time, Bill Harrah owned one of the largest automotive collections in the world, but following his death in 1978, most of his 1450 vehicles were auctioned off. That included 1963 Chrysler Turbine chassis #99123, the car recently sold by Hyman Ltd., which was originally purchased by Domino’s Pizza founder, former Detroit Tigers owner, and noted car collector Tom Monaghan.

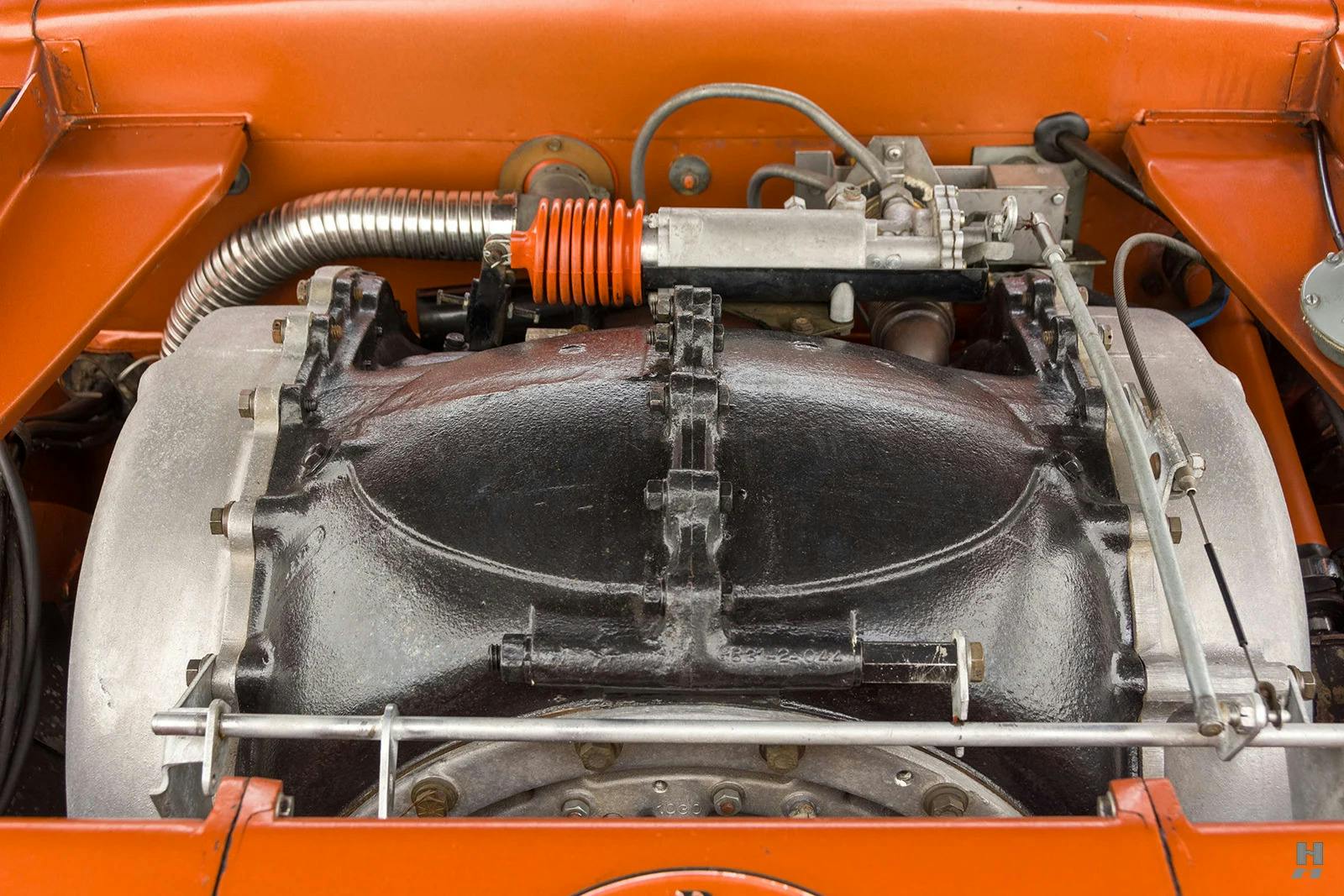

Monaghan sold the Turbine to Frank Kleptz in the late 1980s. It wasn’t running at the time, but in the late ’90s or early 2000s, Kleptz enlisted the help of GE Engine Services to rebuild the engine and make it operational. The turbine makes a modest 130 hp and 425 lb-ft of torque, idles at 18,000–22,000 rpm, and has a comfortable cruising speed of about 70 mph. It remains one of a handful of operational ’63 Turbines.

Beautifully well-preserved in its original condition, chassis #99123 wears its original tires and color-keyed wheel covers. Styling features include three large dash gauges, a stylish center console with unique controls and levers, taillights that look like jet burners, and a horizontal twin exhaust.

Leno showcased his Chrysler Turbine in a 2012 episode of Jay Leno’s Garage, and the video includes some fascinating archival footage and a detailed explanation of how the turbine works. Among the interesting tidbits: the Turbine’s starting procedure. “Turn off engine if temperature exceeds 1600 degrees,” the instructions say. “Engine temperature should begin to drop within two minutes and should stabilize near 1400 degrees within five minutes. Engine must be below 1500 degrees before attempting to move or flameout will occur.” In addition, Leno demonstrates the engine’s lack of vibration by placing a glass of water on top of the cover. The liquid barely shivers.

Rosenbusch says collectors like Leno and author Steve Lehto have helped dispel myths about the Turbine, a practice he also takes seriously. For instance: The car’s exhaust does not get hot enough to burn the ground. The majority of the ’63 Ghia-bodied Turbines were not destroyed “to avoid being hit with import tariffs.” And the ’63 models were not the last of the Chrysler turbine cars.

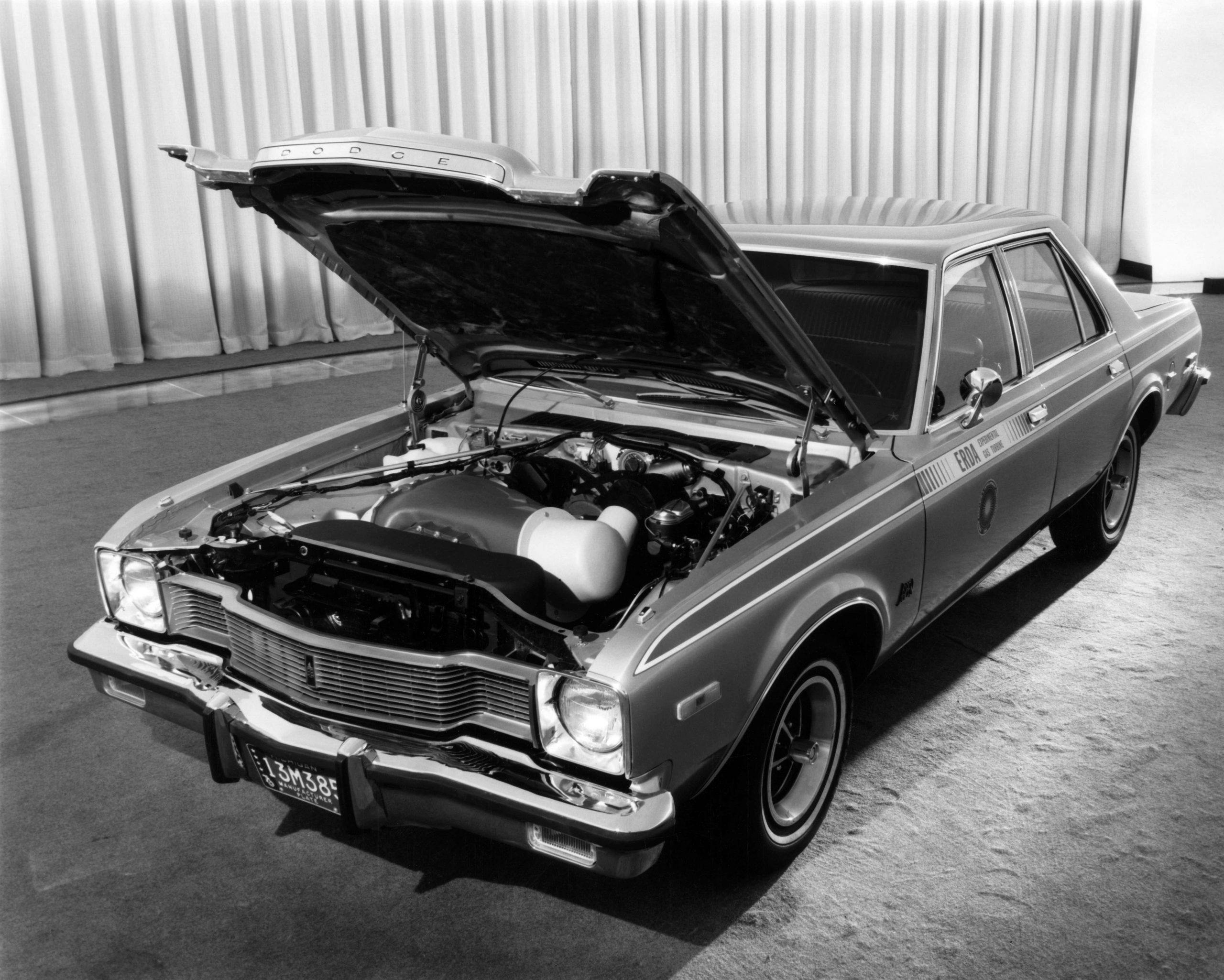

“We went through seven different generations of the turbine engine,” Rosenbusch says. “Most people think the classic Ghia-bodied turbine cars were the only ones we ever produced, but we also put turbine engines in cabover trucks and pickup trucks and Aspens and Volares. There was a constant running turbine car all those years. At the end we worked with the Department of Energy, mostly for funding, but we just never met those set goals.”

The last two cars in the program were a 1978 Chrysler LeBaron and an ’81 Dodge Mirada, both of which the government held onto after the program ended. In the early 1990s, longtime Chrysler turbine mechanic George Stecher spent the final two years of his career looking for those cars. “We owe a lot to George. He eventually found them sitting in a parking lot of a nuclear power plant in Ohio,” Rosenbusch says. “So we picked them up and now they’re in our collection.”

The LeBaron and Mirada are unrestored, but Rosenbusch hopes that some of the former engineers who worked on the turbine project will return and help work on them again. “I think they’re enjoying retirement more than they enjoyed working on turbine cars,” Rosenbusch jokes, “but hopefully we can coax them into coming back for a bit. Even if we don’t get them running, we hope to at least make them displayable.”

Of course, a running turbine car is always the best kind of turbine car. “Whenever we take one out, people just flock to them,” Rosenbusch says. “My wife enjoys going to shows just to see people’s reaction when we start one up. Once you see one and hear one, you never forget it, that’s for sure.”

Forty years after Chrysler halted its turbine engine program, might today’s emphasis on alternative power bring another starry-eyed believer willing to put additional time, effort, and money into the technology? Rosenbusch isn’t optimistic.

“We’ve probably seen the end,” he says. “The M1 Abrams tank runs on a turbine engine, but it has the backing of the entire U.S. Army, which is the kind of massive support you need.

“I think the alternative power sources and alternative-fuel vehicles that companies are turning to now, I think that’s the future. We spent 30 years working on turbine engines, but we never cleared the hurdles that we needed to clear in order to make it relevant going forward. I think it’ll probably stay right where it is.”

The reason most were destroyed is that the bodies were import taxed based on their value, which was high due to the fact that they were hand made. Chrysler destroyed them so they didn’t have to pay the tax.

Chrysler must have had enough money to pay the Tax like anyone does

As this article and Lehto’s well-researched book indicates, that’s not the case. They were destroyed for legal liability reasons.