Media | Articles

Chevrolet’s 409 is a fine way to celebrate 4/09

The ninth of April marks a special place in our hearts, for it is a day in which we commemorate one of Chevrolet’s more famous powerplants: the 409! Before we knew what to call it, the infamous big-block bubble-top Chevys were the foundation of what would eventually lead to the muscle car movement. But to get to where the Bowtie brand’s first big-block came from, we have to start in 1955, with the development that led to its initial offering with the 348-cubic-inch W-series.

The vehicular excess of the ’50s had shown Chevrolet engineers that the humble small-block was being taxed by ever-heavier new models. Especially in the heavier-duty trucks, the engineers wanted more power than the 265-cu-in, and later 283-cu-in, mouse motor could muster without excessive RPM and wear. They needed something bigger.

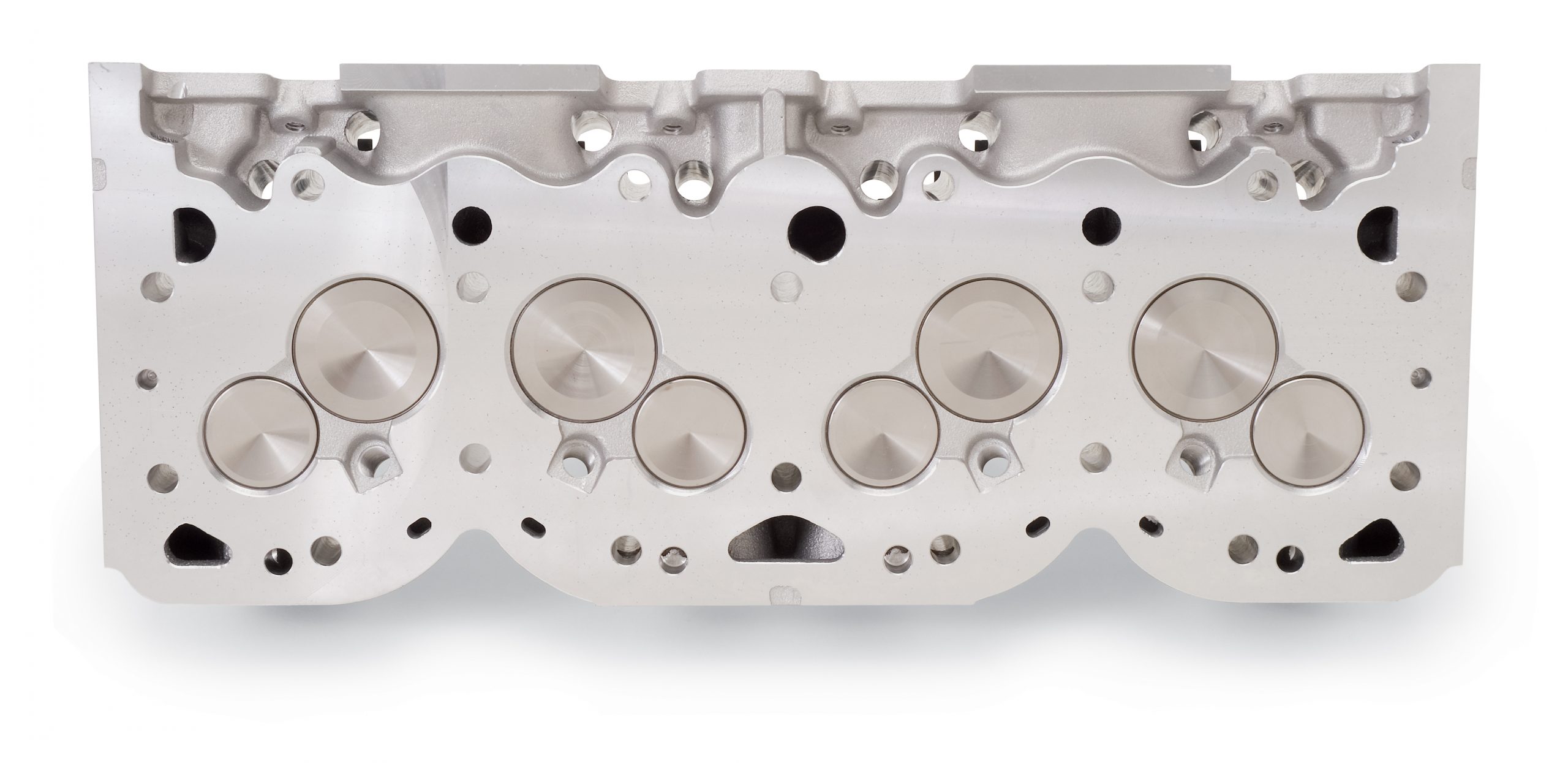

Many of the W-motor’s most iconic traits came out of necessity for Chevrolet. It wanted the new big-block to serve a number of applications, meaning that it would need different compression ratios for the different engine packages. To save on expensive cylinder head tooling, the W-motors instead used a 74-degree deck—as opposed to the traditional 90 degrees— to create the space for the combustion chamber in the block while the heads were machined flat. This meant that instead of retooling the cylinder heads with different-sized combustion chambers before they were cast in molten iron, the compression ratios could be easily changed by using pistons with different dome volumes to create the final combustion chamber volume in the angled deck. The resulting 16-degree wedge-shaped combustion chamber between the head and piston was efficient for its day. When combined with a 4.125-inch bore and 3.25-inch stroke, it gave the motor the low RPM grunt demanded by buyers when it was introduced in 1958 as the 348-cu-in Turbo-Thust series of engines. Underneath the famous scalloped valve covers were staggered valves, which help keep the big-block as compact as possible.

Horsepower ranged from 250–350 by the end of its production run, thanks in part to the iconic 3×2 progressive carburetor setup with three two-barrel Rochesters. These things began to fly off the shelves with four-speeds and positraction differential tacked onto the order sheet as the new big-block found itself as a tool at the track in the Impala SS. By 1961, however, Chevrolet had finally done what it always does to its best ideas: added more cubic inches.

The 409-cu-in big-block was born with an additional 1/4-inch of stroke (3.5-inch total) and another 3/16-inch in the bore for 4.312-inch slugs. GM eventually designed a new engine block for the 409 with thicker cylinder walls, warning that boring the 348 block led to cracks. This increase in bore also unshrouded the exhaust valves, no longer necessitating the notch seen in the 348’s smaller-diameter combustion chamber, and it gave Chevrolet a real fire-breather for the racers. The heads were essentially the same, but the valvetrain received several minor updates to beef it up for increased spring pressures and hotter cams. The 409 hit the streets with a stout 360 horsepower with the base single-four barrel carb, and 380 hp with a dual-quad setup. It would receive minor changes in 1962 as the engine found its groove in NHRA and stock car racing—including much-needed larger valves—and some random kids from Hawthorn decided that the hi-po 409, with a dual-quad, four-speed, and positraction backing it, was worth singing about. And it wasn’t just Chevrolet that had its fun with the W-motor, but also Pontiac. Well, Pontiac-Canada, which carried its own models that rode on Chevrolet chassis with Chevrolet drivelines, but wore Pontiac’s own unique sheet metal and badging, including the “Super-Flame” branded Chevy 409s.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Thankfully, the 409 backs up its lore with some brutal accomplishments. The Z11 package, Chevrolet’s answer to its lighter competition, became a wicked sleeper success when it was introduced. The 427-cu-in masterpiece kept the 409’s bore but increased the stroke to 3.65 inches. The new rotating assembly managed to squeeze out a 13.5:1 compression ratio, and when fed by the dual-quad Carters on a new aluminum intake manifold stamped out 430 hp and 435 lb-ft of torque. This would be the swan song of the W-motor, as its next-generation replacement was already throwing punches in racing as the infamous Mystery Motor.

While its role was transitional in Chevrolet engine development, the W-motor’s mark on the world has been everlasting thanks to its rapid escalation of performance as we entered the ’60s. The now inescapably venerable 409, four-speed combo is an icon in the beams of Pomona as it was on the banks of Daytona. For Chevrolet, it ushered in an era of big-cube performance and trickle-down engineering that will probably never be seen again.

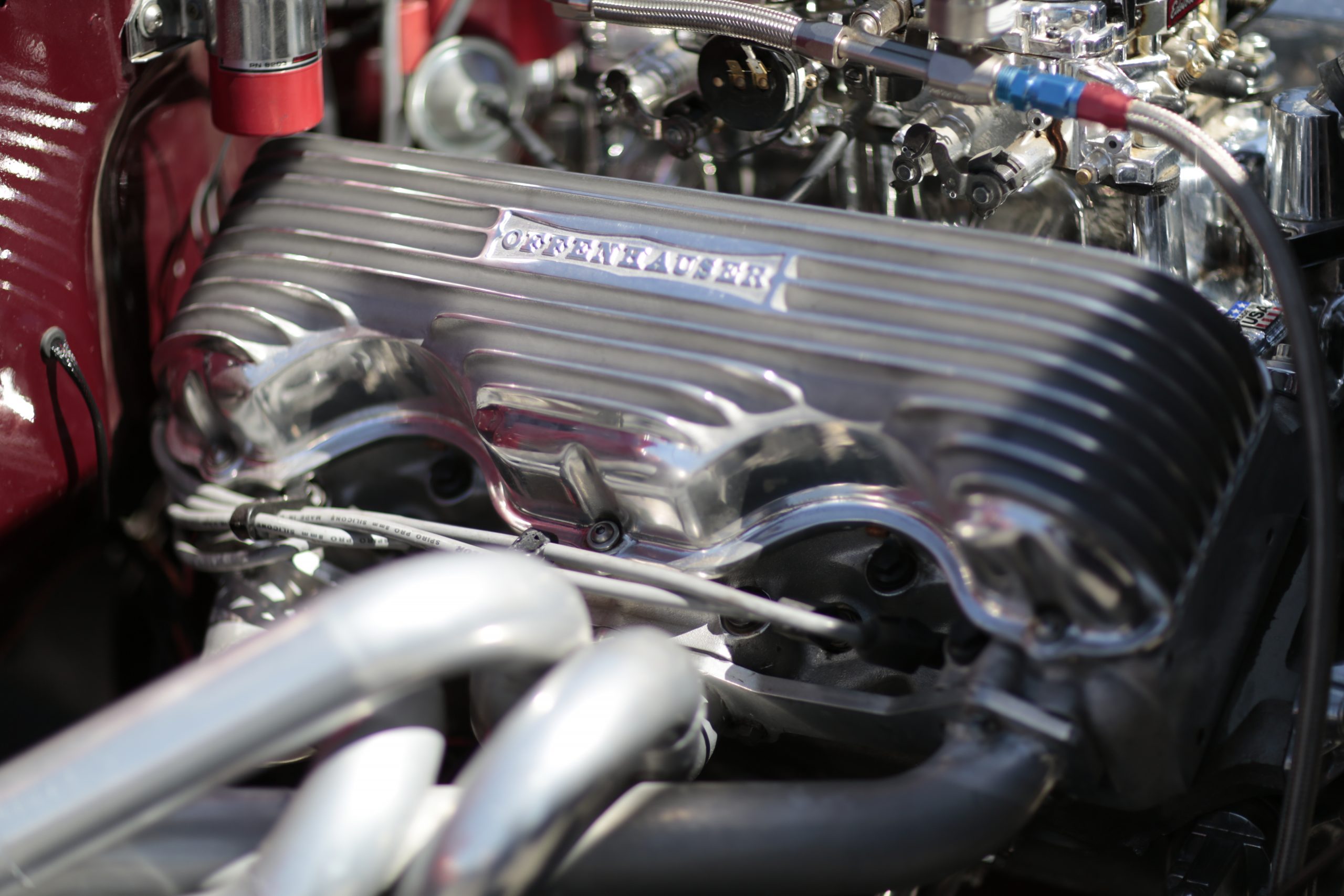

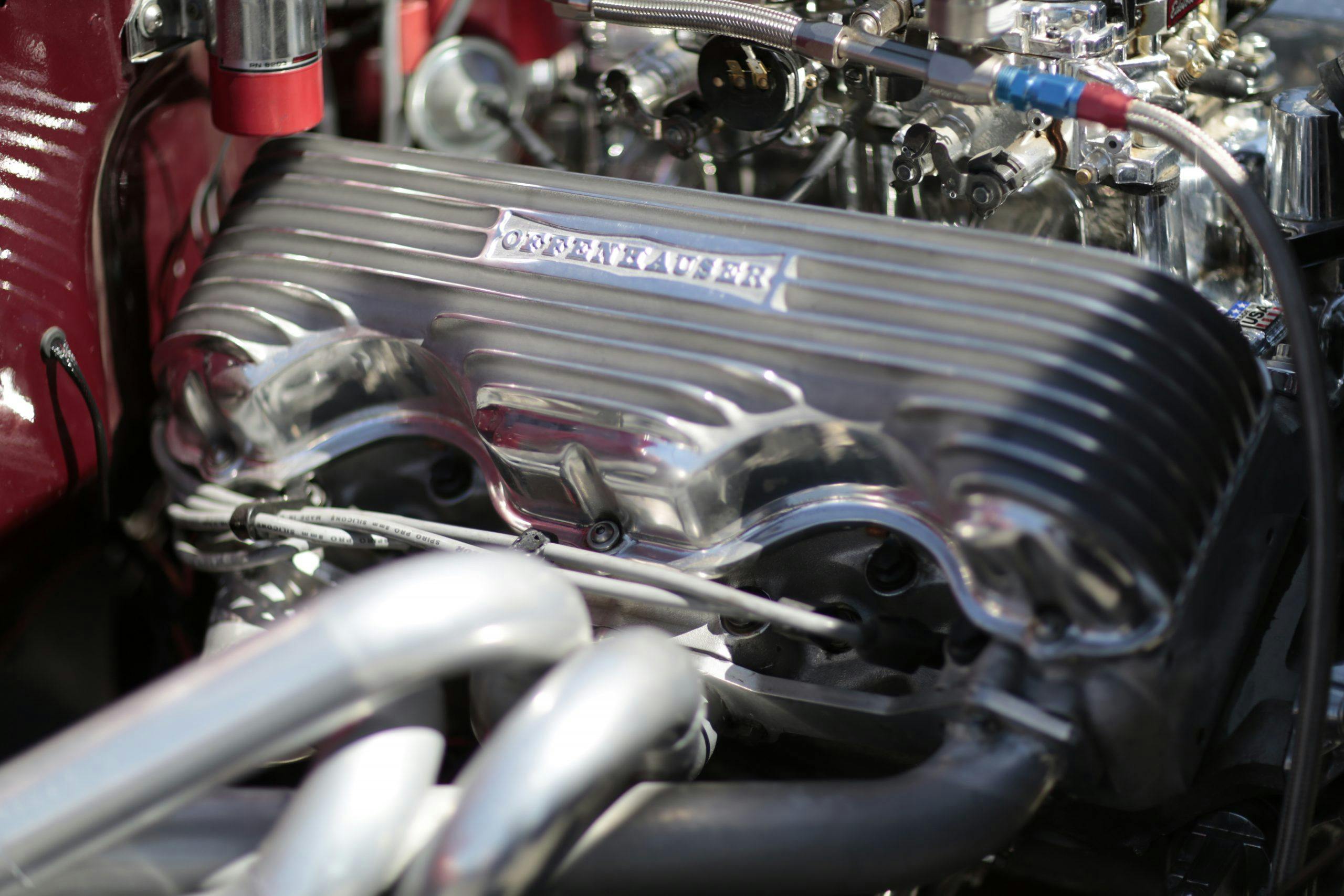

So the next time you see those upside-down W valvecovers between the fenders, you’ll know a little more about Chevrolet’s first big-block.