Media | Articles

Catching a Fifth Avenue double-decker bus ride into the past

New York City’s Fifth Avenue Coach Company was the Cadillac of American bus companies for nearly five decades, from at least 1906 until 1954. It was popular, profitable and quick to adapt to new ideas. It attracted skilled designers and administrators worldwide, who exported their talents to other major U.S. cities—particularly Chicago.

Most memorably, the company ran 160 “Queen Mary” streamlined double-decker buses along its namesake Fifth Avenue from 1936–53. The buses’ rear-engine, low-floor design was so revolutionary that it’s still being copied today. Each bus traveled an estimated 1,000,000 miles in service.

Fifth Avenue Coach Company’s genesis is peculiarly American. In 1885, Fifth Avenue was bordered by huge mansions—“Millionaire’s Row”—occupied by such families as the Astors, Vanderbilts, and Whitneys, all of whom were determined to prevent trolleys or subways from being built in their front yard. They threw considerable weight behind New York City’s decision to ban anything but buses on the main thoroughfare.

The Fifth Avenue Transportation Company was established in 1885. Fares were set at 10 cents—double that of other bus companies—and cynics observed that the real purpose was to transport servants to church on Sundays and keep out the riff-raff. Handicapped by competitors’ 5-cent tickets and the fact that most people on the avenue had their own carriages, the company lingered until 1895, when it failed and was reformed as the Fifth Avenue Coach Company.

The new company operated horse-drawn buses until 1907 (after unsuccessful trials of electric units in 1899), then British- and French-designed gasoline-powered double deckers until World War I cut off the supply. Converting to American-built Brill buses, the company prospered after the Great War. It steadily expanded its routes and reported carrying 51 million passengers in 1921, up 8.5 million from the year before.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Fifth Avenue Coach executives were in demand elsewhere; key figures were hired at the Chicago Motor Coach company, which also used double-decker buses. Yellow Cab magnate John Hertz had taken over the Chicago bus company in 1922, when he was selling 95 percent of the taxis in the U.S. Hertz expanded into buses, then in 1925 sold the Yellow Coach Company to General Motors, which took over bus manufacture.

Height issues discouraged the use of double-decker buses in the U.S., since much bridge construction preceded their arrival. It was initially solved by open-top buses, then ingenious dropped floors with front engines tilted downwards to lower drivelines.

However, in 1934 a breakthrough design appeared from engineer Dwight Austin, who brought his rear-engine “angle-drive” or “V-drive’ technology from Pickwick Coaches in Long Beach, California. In 1928, Austin developed luxury overnight “Nite Coaches,” which foresaw first-class air travel in all but speed and flight. Pickwick filed for bankruptcy in 1932 and Austin was looking for work.

His Chicago and New York double decker buses were revolutionary. The conventional front-engine 1300 Series buses they replaced carried 56 passengers—23 on the lower deck and 33 on the upper deck. Austin’s low-loader 720 and 735 models could carry 72 passengers—31 on the lower deck and 41 on the upper level.

Austin’s design was developed for his 10-foot-high, 35-foot-long Nite Coach, then tested in a single-decker Greyhound bus. It placed a 174-horsepower, 707-cubic-inch GM gasoline engine transversely at the rear. The automatic transmission was located on the left side of the engine, and the driveline was only about 6 feet long, angled to a central differential on the solid rear axle. The engine’s location meant it could be rolled out and replaced in a single work shift, says Motor Bus Society Chairman Jim Gilligan, a lifetime bus industry executive.

The 720 and 735 double-decker buses were 33 feet long and all-aluminum. Due to their size and streamline design, they were immediately tagged as “Queen Marys” for the famous Blue Riband ocean liner. Thanks to the rear-mounted engine and transmission, the frame could be dropped between the axles, and the overall height of the low-roof 720 was only 12 feet, 11.5 inches. Fifth Avenue Coach ordered 60 of the low-roof 720 buses from 1936–38, while the Chicago Motor Coach Company bought 100 of them, since they would fit under the city’s elevated railways. Fifth Avenue Coach also bought 100 high-roof 735 models, which were 13 feet, 5.5 inches tall, creating 68 inches of headroom upstairs (as opposed to a restrictive 63 inches), and they were used on routes with no height restrictions, like Riverside Drive.

Passengers embarked at a door behind the right front wheel and dismounted at the rear, while a wide staircase led upstairs on the left side, behind the driver. The buses were designed to be driver-only, but that proved to be impractical. A New York union contract required conductors until December 1946, and when they were removed, passengers had to pay as they entered. Loading slowed so much that tickets had to be sold on the sidewalk in advance, and the Queen Mary’s days were numbered.

In 1954, Fifth Avenue Coach was taken over by the New York City Omnibus Corporation, and the flagship Queen Mary buses were retired. They plied their trade in Manhattan for almost 20 years, each covering 1,000,000 miles and wearing out three engines and five transmissions before they were sidelined. Like the Supersonic Concorde airliner, they were never significantly uprated.

London’s Routemaster dimensions were similar to Austin’s 720 and 735 designs, but the Queen Marys were 3 feet longer (at 33 feet total) and managed to accommodate about 10 more passengers. Austin’s aluminum construction shaved off 5000 pounds from the equivalent English design, and his 707-cu-in GM gasoline engine produced 60 more horsepower than the 600-cu-in British diesel. GM’s automatic transmission was also far simpler—a two-speed automatic.

The design of the rear-engine Model 720 and Model 735 bus was rediscovered 20 years later in London—surely the cradle of double-decker bus design. Sadly, the rear-engine Leyland Atlantean was less efficient and less reliable than the older American design. The last Atlantean was withdrawn in 1986, while conventional AEC Routemasters persisted until 2005.

A small number of Atlanteans were tested in New York City in 1976, but they proved to be a) too tall for Fifth Avenue at 14.5 feet, b) unable to cope with New York’s potholes, and c) lacked efficient air conditioning. They lingered until 1980.

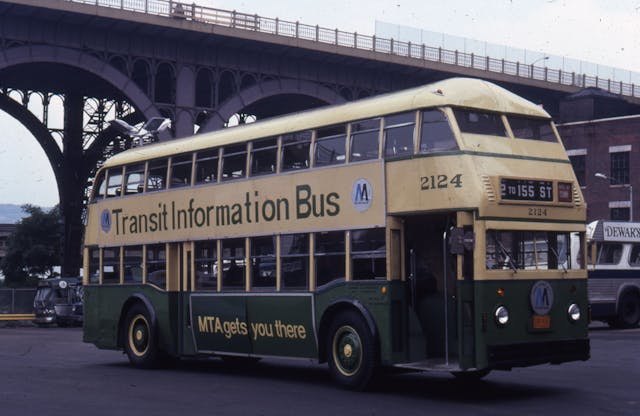

London Transport’s Routemaster is considered the classic double-decker bus. A total of 2876 were built, of which 1280 survive today. Tragically, few Queen Marys survive. The final 735 bus produced, no. 2124, is nicely restored in its cream-over-green livery and provides sentimental cruises down Fifth Avenue on special occasions, but there is little trace of the remaining 159 New York City streamliners. The fate of Chicago’s 100 low-roof 720s is equally murky.

Motor Bus Society records traced 735 no. 2094 to the Long Island Auto Museum, then the Harrah Collection in Reno, Nevada, and finally to Mark Smith in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, in 1985. Two other 735s—nos. 2097 and 2124—were sold to Bornscheuer Bus Co. on Long Island, then no. 2097 went to tour operator Chicago Motor Coach Co. It was last reported owned by London Limos of Wilmette, Illinois.

Meanwhile no. 2124 went to the Washington Square Inn in New York, then the Manhattan and Bronx Surface Transit Operating Authority in 1969. It is now preserved by the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority. Bornscheuer Bus Co. also bought no. 2013, which is derelict in Farmingdale, Long Island. No. 2015 has been preserved in the National Museum of Transportation in St. Louis.

Apart from New York and Chicago in the 1930s and ’40s, double-decker buses are relative novelties in American cities. Davis, California; San Luis Obispo, California; and Las Vegas run a few on specific routes, while Los Angeles and San Francisco use them for longer commutes.

Unconventional Seattle employs 89 English-built Dennis double-decker buses in outlying areas. The city also has an 80-year love of trolleybuses, which could switch from electric power downtown to diesel gasoline power in the suburbs. The latest advances in battery technology suggest Seattle was on the right track.

New York City still has occasional trials of double deckers, most recently under British-born Andy Byford, who was president of New York City Transit Authority from 2018–20. In 2018, a test program brought an enormous 81-passenger, 10-wheeled Dutch Van Hool double decker to the city, but again the idea didn’t catch on and Byford returned to London.

These days, no. 2124 is the only Queen Mary likely to be seen at work. On special occasions, the NYCTA runs the very last 735 on its original routes. If you’re in Manhattan on the right day, you might just hop a ride into the past.

For your information, one of the Fifth Avenue Queen Mary’s sat parked near some warehouses in Santa Clarita, California until the early 2000’s. I assume that it had been used as a movie prop. I am not sure a out it’s condition. I tried to get close to it to photograph the bus but the facility’s guard chased me away and offered me no information about the bus and what it was doing parked in Santa Clarita,California.