Media | Articles

BMW’s most significant engine didn’t have six cylinders

Today’s car enthusiasts adore BMW’s remarkable inline sixes (L-6s), but it’s worth recalling that these engines descended from one of the world’s most astute L-4 designs.

After WWII allies bombed their factories to smithereens, German makers needed a decade or more to rejoin the car business. In 1960, following the failure of the Bayerische Motoren Werke’s attempt to return Germans to the road with Isetta-designed microcars, the company was bailed out of bankruptcy by industrialists Harald and Herbert Quandt. (With assets topping $39 billion, the Quandts are still Germany’s wealthiest family.) That rescue enabled another go in 1962 with a range of small sedans BMW called its New Class.

Engine chief Alexander von Falkenhausen was tapped to design the New Class powerplant. Certain that larger, more powerful engines would be essential to fulfill BMW’s aspiration—cars aimed at aufsteigers (social climbers)—von Falkenhausen unceremoniously rejected the 1.3-liter displacement he was assigned. Instead, he convinced his bosses that 1.5 liters was the appropriate starting size, with room for growth to 2.0 liters absolutely essential. This wisdom ultimately paid dividends neither von Falkenhausen nor his BMW colleagues could have imagined.

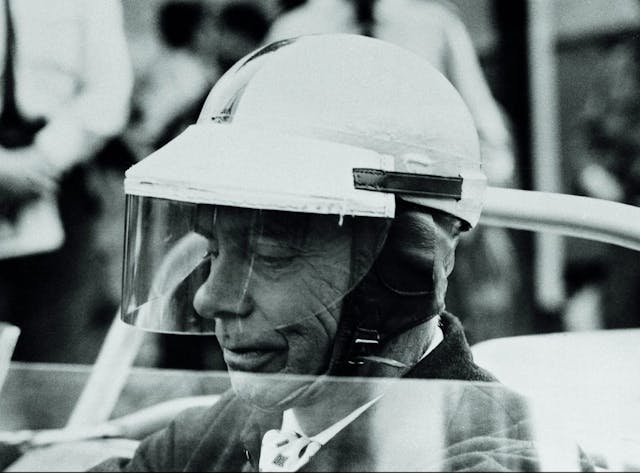

Von Falkenhausen—later dubbed BMW’s Baron—joined the Werke in 1934 as a racing motorcycle rider and designer upon graduating from Munich’s Technical University, where one of his professors was aircraft genius Willy Messerschmitt (who later became a leading German armament manufacturer). Von Falkenhausen earned victories in the 1936 and 1937 International Six Day Trials using an experimental rear suspension, which convinced BMW to approve that feature for series motorcycle production. In preparation for WWII, he worked on sidecar applications and armored vehicles, including a tank powered by BMW’s nine-cylinder radial aircraft engine.

After the war, von Falkenhausen won the 1948 German Sports Car Championship driving a BMW 328 and other home-built cars. His own AFM race car manufacturing enterprise failed in spite of his decent Formula 2 finishes in 1952 and ’53 (against Cooper, Ferrari, and Maserati), prompting his return to BMW in 1954. After three years onboard, he became head of engine development.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Defying BMW’s prewar tradition of powering its cars with L-6s, von Falkenhausen selected an L-4 design for his M10 engine to maximize the New Class cars’ cabin space. BMW had ample experience with aluminum for aircraft and motorcycle engines, but von Falkenhausen picked cast iron for the block for two reasons. Though iron weighs nearly three times as much as aluminum per unit volume, it’s 50 percent stiffer. And, unlike aluminum, the iron bore surfaces would be durable without liners or expensive surface treatments—important considerations for a carmaker striving to get back on its feet.

Von Falkenhausen did select aluminum for the cylinder head before that was common practice. One notable exception was Chevy’s Beetle-inspired Corvair, which had aluminum crankcase and head components. Bolt-on parts such as the M10’s front cover, intake manifold, and clutch housing were also aluminum.

A key von Falkenhausen achievement was convincing company superiors that a forged-steel crankshaft supported by five main bearings was a necessary expense. His bosses would have preferred a simpler cast-iron crank carried by three bearings to cut costs. In addition, von Falkenhausen extended the sides of his block (a.k.a. skirts) well below the centerline of the crankshaft to enhance the stiffness of the engine and transmission assembly. A more rigid powertrain combo minimizes flexing at high output levels, thereby reducing noise, vibration, and harshness in the car’s cabin.

Bottom-end rigidity is crucial in any engine with performance aspirations because the crankshaft—a long, kinked rod with each offset mated to a connecting rod—effectively serves as the powerplant’s legs. At high rpm, significant flexing can trip the engine, resulting in the car equivalent of a broken leg.

Tapping his decade of motorsports success, von Falkenhausen configured the M10’s valvetrain with a chain-driven overhead camshaft opening two valves per cylinder via rocker arms. Hemispherical combustion chambers and a bore significantly larger than the stroke provided room for large valves, aiding volumetric efficiency (flow in and out of the engine) at high rpm, thereby raising power without harming fuel economy.

Canting the block 30 degrees from vertical lowered both the New Class’s hood and its center of gravity. Doing so necessitated a specially shaped oil pan.

The resulting M10 1.5-liter with an 82-millimeter (3.23-inch) bore and 71-millimeter (2.80-inch) stroke delivered 80 horsepower at 5700 rpm and 87 lb-ft of torque at 3000 rpm, potent figures for a small engine in the early ’60s. The torque curve was nearly flat from 1750 to 4850 rpm. BMW’s new L-4 weighed about 350 pounds, only 100 pounds more than the VW Beetle’s 40-hp, 1.2-liter flat-four.

Car and Driver first experienced the M10 in its review of a 1963 BMW 1500, calling that boxy four-door “an extremely pleasant and sensible automobile capable of outperforming more powerful cars, including some two-seaters.”

After progressing through 1.6- and 1.8-liter editions, BMW launched its 2.0-liter 114-hp 2002 two-door on a 2-inch-shorter wheelbase for 1968, moving Car and Driver to religious fervor. Reviewer David E. Davis, Jr., rated this BMW “the best $2850 sedan in the cotton-picking world,” and told readers to turn their hymnals to page 2002 to “sing two choruses of Whispering Bomb” (the 2002’s nickname). A 1970 road test of a 2002 equipped with a four-speed manual transmission reported 0–60 mph in 9.6 seconds and a top speed of 111 mph. What BMW had wrought here was the seminal compact sport sedan.

Replacing the M10’s single-barrel carburetor with twin Solex two-barrel side-drafts brought 20 more horsepower and a ti suffix to the 2002’s nameplate. In 1972, fuel injection arrived, raising output to 140 horsepower and changing the model designation to 2002 tii. (The 2002 ti wasn’t imported to the U.S.)

For combustion to occur, gasoline must be vaporized and mixed with air. Unlike carburetors, which simply add liquid drops to the airstream, injection atomizes the fuel into microdroplets that quickly vaporize when exposed to cylinder-head heat. The 2002 tii’s Kugelfischer system was timed to squirt a precise dose of fuel into each intake port in synch with the opening valve.

In general, longer intake manifold runners enhance low-rpm torque due to resonance effects that ram more air into the combustion chamber. Shorter, less restrictive runners increase high-rpm output. While electronically controlled fuel injection had been introduced in the early ’70s to meet tightening exhaust-emission requirements, BMW was late to join that party. The strictly mechanical Kugelfischer system added 26 horsepower, trimmed precious tenths off the 0–60-mph time (9.0 seconds), and added a few mph to top speed.

The M10 L-4 powered more than a quarter-million cars by 1970, becoming so dear to BMW that Austrian architect Karl Schwanzer was commissioned to configure its new Munich world headquarters as four round office towers. Instead of resting on the ground, these 22-floor cylinders are supported by a low-key center structure. A nearby bowl-shaped building resembling a cylinder head houses the company museum. Following four years of construction, BMW’s striking headquarters opened just before the start of the 1972 Summer Olympic games.

The following year at the Frankfurt auto show, BMW presented a 2002 Turbo, the brand’s first car equipped with a boosted engine. The KKK turbocharger teamed with Kugelfischer injection hiked output to a hearty 170 horsepower. Unfortunately, BMW’s timing could not have been worse. Mere weeks after the Turbo’s debut, OPEC switched off the taps, plunging the world into the first oil crisis. Only 1672 Turbos were manufactured, distinguishing that 2002 as one of the rarest and most prized BMWs.

A new 320i, code-named the E21, replaced the aging 2002 in 1976, the year von Falkenhausen retired from BMW. (He died in 1989 at 92.) The faithful M10 carried on in 2.0-liter form in this first 3 Series, now fed by Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection, a more sophisticated but still purely mechanical system. Emissions controls dropped output to 110 horsepower. That plus 300 or so pounds more curb weight resulted in the 320i’s 10.5-second run to 60 and a 108-mph top speed (clocked by Car and Driver).

In the late ’70s, turbo kits were all the rage to counter the evil effects of emissions controls. Reeves Callaway, a Connecticut motorsports entrepreneur, created an ingenious bolt-on turbo kit for BMW’s 320i in 1977. This $1200 package, distributed through aftermarket specialists Miller & Norburn, worked quite nicely, trimming 2 full seconds off the quarter-mile elapsed time and adding 17 mph to the 320i’s top speed. Callaway went on to turbocharge several other cars, including factory-fresh Chevy Corvettes dropshipped to his installation center. His tuning businesses located on both coasts thrive to this day.

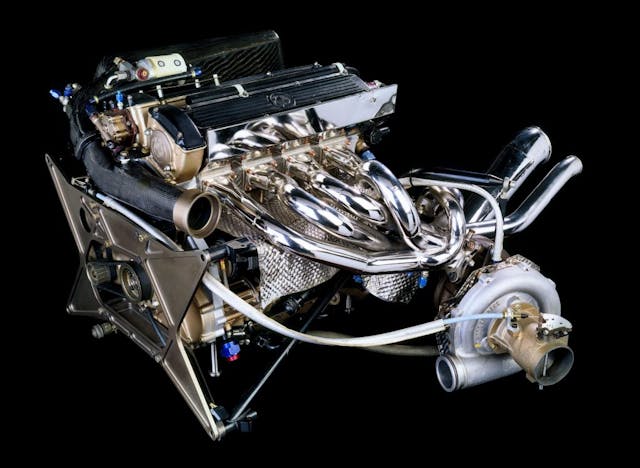

BMW’s venerable M10 also played a pivotal role in motorsports. Von Falkenhausen’s stout 1.5-liter L-4 was relabeled M12/13, bored and destroked to 2.0 liters, equipped with tougher titanium connecting rods, and fitted with a gear-driven twin-cam 16-valve cylinder head for Formula 2 competition, where it produced 300 horsepower. The new head designed by Ludwig Apfelbeck had hemispherical combustion chambers and an unusual radial intake-exhaust-intake-exhaust valve array intended to generate swirl in the cylinder, which enhanced exhaust-valve cooling.

Valve stems poked out the top of each combustion chamber like coronavirus spikes. Intricate rocker arms opened the valves and exhaust pipes sprouted out both sides; intake ports were atop the head between the camshafts. In spite of its complication, BMW’s M12/13 dominated Formula 2, winning six championships in March cars between 1973 and 1984.

In 1982, BMW progressed to Formula 1 with the only engine in the series derived from a mass-produced block. Nelson Piquet had an auspicious start, winning the Canadian Grand Prix in a Brabham powered by a 1.5-liter aggressively turbocharged M12/13 boosted to 640 horsepower. Simplicity versus the twin-turbo V-6s raced by Ferrari and Renault proved to be the M12/13’s secret weapon. Piquet won the World Drivers’ Championship in 1983, the first for any turbocharged single-seater.

By 1986, engineers had tuned this screamer to an awesome 1400 horsepower for qualifying, an intelligent guesstimate because BMW lacked a dynamometer capable of measuring such lofty outputs. That said, there’s little doubt that the BMW turbo M12/13 was the most powerful Formula 1 engine ever to race. During five seasons, it helped earn 15 pole positions, 14 fastest race laps, and nine victories in the hands of Brabham, Arrows, and Benetton drivers.

One snippet of lore shared by Britain’s Ridgeway Racing Engines is that M10 blocks were requisitioned from road cars that had logged 60,000 or more miles to rid their castings of residual internal stresses. The blocks were allegedly seasoned outdoors for several months and occasionally urinated on to infiltrate their cast iron with nitrides for added strength. (Urine contains urea, a hydrogen-nitrogen-oxygen compound, and treating iron with nitrides is a common means of increasing surface hardness.)

In 1987, BMW introduced its fresh M40 L-4, ushering the venerable M10 into retirement. Let the record show it served magnificently for more than a quarter-century, supplying dependable power to 3.5 million BMW automobiles.

Clearly, the visionary von Falkenhausen had wielded a magic wand designing an engine that endured a 17-fold power increase—from its 80-hp beginning to 1400 in F1 qualifying trim. And when BMW needed a potent L-6 to power its upmarket sedans in the late 1960s, the astute von Falkenhausen created fresh 2.5- and 2.8-liter M30 L-6s the most expeditious way possible—by simply tacking two more cylinders onto his celebrated M10. With von Falkenhausen’s brilliance calling the engine-design shots, BMW was off and running with new L-6s that earned lasting admiration from car enthusiasts.