Media | Articles

Before It Went Into Aviation, Rolls-Royce Built a One-off Balloon Car

Coachbuilding in the prewar period was all about what the British call “horses for courses.” In other words, a distinguished and demanding buyer would purchase a rolling chassis for speed and reliability, and then order a custom body suited to the type of expected use. Something swishy and chauffeur-driven, meant to flex on your fellow hoi-polloi? That’ll be a town car bodywork, only really suitable for rolling up to the red carpet. Or perhaps it’d be slippery Brooklands-style aerodynamics for the steely-eyed, tweed-clad tillerman. Or you could, you know, get something to carry your hot air balloon around.

Yes, really, a pre-war balloon car. And when we say pre-war, the roots here stretch back to Edwardian times, prior to The Great War that would cut short the lives of so many sons of aristocratic houses. It was a time when the dawn of aviation and the rise of the automobile were tightly linked, when the fastest man in the world was a guy on a hilariously dangerous airplane-engined motorcycle. And it was a time when Charles Rolls, co-founder of Rolls-Royce, was deeply interested in bags of hot air—just not those who were his cousins.

The Honorable Charles Stewart Rolls was one of those larger-than-life characters that, had a novelist invented him, would be considered too odd to be believable. He was the third son of an actual Baron, and his was a noble family with a strong military tradition and the rather excellent motto, Celerias et Veritas (speed and truth). Pretty good slogan for a car company, don’t you think?

Chas Rolls was a lanky six foot five, smoked like the Flying Scotsman at full speed, and was a vegetarian. He had almost no time whatsoever for the snobbery of his well-heeled relatives, was acerbic of wit, and was so obsessed with engines that he picked up the nickname “dirty Rolls,” because he was so often covered in oil and grease.

Educated at Eton and Cambridge, he might well have gone on to be a great industrialist. The third sons of great houses often have quite a lot of time on their hands, as they are not often the chosen heir, but in fact, the Rolls lineage would end with him and his brothers, the eldest of them dying of wounds suffered at the battle of the Somme and Charles’ life cut short by the pursuit of his passions rather than war.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

A racing cyclist while at Cambridge, he bought his first car at the age of eighteen, having to travel to France to do so. That car, a Peugeot, is thought to have been the first automobile in the Cambridge area, and when he drove it back to his family home, it was one of only three such vehicles in Wales. This was the era of the Locomotive Acts, where top speeds were highly regulated, and Rolls co-founded the Automobile Club of Great Britain to campaign for less restrictive roads.

He was something of a daredevil, and in 1903 set the unofficial land speed record, hitting a heady 83 mph in Dublin, Ireland (Ireland having less draconian speed laws at the time). The timing equipment was not properly validated, so Rolls didn’t get his name officially on the, er, rolls. At this time, he also began importing cars from Belgium and France into the U.K. as a way of paying for his automobile racing.

The famous meeting with Henry Royce happened on May 4, 1904. Royce was from a completely different background than Rolls, a commoner who hawked newspapers as a child and apprenticed at fourteen to The Great Northern Railway. He’d bought an early French automobile second-hand, taken it apart, and made a number of improvements. Just one month prior, he’d created a two-cylinder car of his own construction, and it was this that captured Rolls’ attention. They formed a partnership immediately.

By this time, Rolls was already an accomplished aeronaut. He was a co-founding member of the Royal Aero Club, and in 1903 had won the Gordon Bennett gold medal for the longest flight time in a balloon. Even as he was pressing for speed on the ground, he had his head quite literally in the clouds.

In 1906, Rolls-Royce presented the model that would cement the company’s early reputation: the 40/50 hp, better known later as the Silver Ghost. With a durable six-cylinder engine, this car would adventure all over the world, sold to the Maharajahs of India, fighting guerilla tactics in the desert with Lawrence of Arabia, or being pressed into service as a fighting armored car.

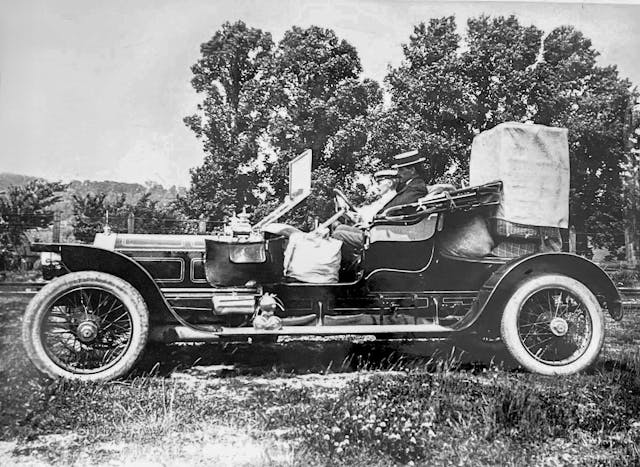

In 1908, Rolls had the 70 hp 40/50 chassis number 60785 sent to the well-regarded H.J. Mulliner coachbuilding company, and fitted with a unique body. Officially a roadster style, it featured a large rear platform for storing the wicker basket of a small hot air balloon, and even had patent leather flexible rear fenders to make loading and unloading the basket much easier. It quickly picked up the unofficial name of the Balloon Car.

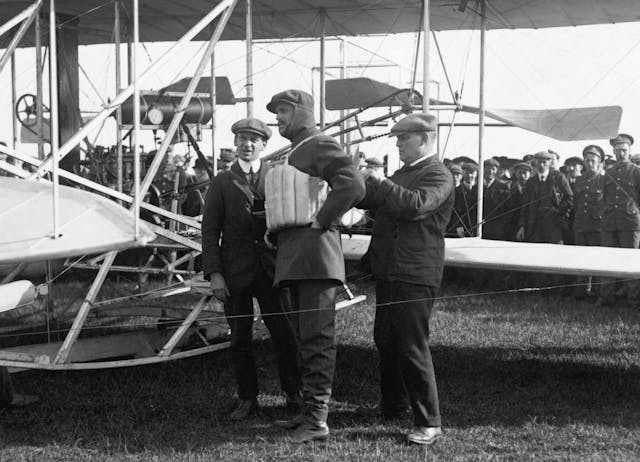

The car was used as support in several flights, but Rolls himself soon turned away from ballooning to heavier-than-air flying. He hosted the Wright brothers on a visit to the U.K., then later purchased himself a Wright Flyer, racking up more than 200 sorties in short order. In 1910, he became the first person to overfly the English channel there-and-back again, landing in Dover to cheering throngs of thousands.

Sadly, only one month later, his fragile biplane disintegrated in midair during a flying competition, plunging to earth. Rolls was killed instantly, the first British person to die because of an airplane crash, and one of only about a dozen aviation pioneers to have lost their life at the time.

The Balloon Car itself was sold on, but went missing in the early 1920s. It may be lurking in some British shed somewhere, waiting to be found. In the meantime, various replicas have been built of it, the most faithful of them commissioned by noted Rolls-Royce collector Millard Newman. For a time, one of these was on display at the Harrah collection in Reno, Nevada.

Rolls-Royce itself went into the aviation business in 1914 as a result of the outbreak of war, and today produces many jet engines for the commercial aviation industry. Last year, it built the world’s largest jet turbine, dubbed UltraFan, good for a staggering 85,800 hp.

You’d have to think Charles Rolls would approve of the fact that companies bearing his name provide excellence both on the ground and in the sky. And perhaps someday, some wealthy client will ring up their local Rolls-Royce dealer to say, “I’m sure the Cullinan is fairly practical, and the Phantom extended exudes plenty of presence—but what do you have that’ll haul my hot air balloon around?”

Great article, Brendan – as per usual. Great story with a sad ending. I am sure Royce carried on the tradition Rolls and he started, but there is always the ‘what if…’.

Why do I now need to “Accept Cookies” with every new article??

EXTREMELY ANNOYING. So much so that it takes away the joy of reading Hagerty!!!

Very cool car. I like how the back end flows out. Looks like it would work great for carrying more than just balloons back in the day.

Great article! A fancy pick-up. :>)

Contrary to popular belief, hoi polloi means the common people, not the upper class, and is usually meant in a disparaging way. Hardly the sort of people who bought custom-bodied automobiles. It’s also not hyphenated.