Media | Articles

At Your Next BBQ, Tip Your Chef’s Toque to Henry Ford, Who Helped Popularize Charcoal Briquets

While there are those of us, like Hank Hill, who prefer “clean burning propane,” there are plenty of backyard barbecuers that would rather do their grilling over hot coals, specifically charcoal briquets. If you’re wondering how that is an appropriate topic for an automotive site, it’s because charcoal briquets were in great part popularized by Henry Ford.

Aha, you may think, so that’s why the brand is called Kingsford. In fact, that’s not the case; there was actually a person named Kingsford for whom the brand is named, though the company that is now known as Kingsford originally did market its products under the Ford brand.

In 1890, 20-year-old Edward G. Kingsford married Mary Flaherty of Iron Mountain, Michigan, a town in the state’s Upper Peninsula on the border with Wisconsin. “Minnie” Flaherty was a first cousin to Henry Ford, who then worked for the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit. While Ford was working for Thomas Edison during the day while developing his Quadricycle motorcar by night, Kingsford was making a career out of the north woods as a timber “cruiser” and logger and selling timber and real estate across the U.P.

The two men had a camaraderie, both being hardworking and industrious sorts. Over time they became fishing and hunting buddies, as Ford developed a love for northern Michigan. Ford would sometimes use Kingsford as a sounding board or advisor to get opinions outside of Ford Motor Company management in Dearborn.

In 1908, the year that the Ford Model T was introduced, Edward Kingsford was granted distribution rights for Ford automobiles for the entire Upper Peninsula and northern Wisconsin, opening up a number of dealerships. As Model T production soared, selling over a million cars in 1919, Ford Motor Company’s need for wood rose proportionately. While the automobile is seen as a product of the industrial age, something made of iron and steel, early cars used a lot of wood. The body panels may have been steel, but those panels were mounted on wooden frames. Floorboards, dashboards, and spokes for wooden “artillery” style wheels consumed trainloads of wood. It’s estimated that every Model T used about 100 board-feet of lumber in its construction.

Henry Ford believed in vertical integration. In time, he owned iron mines, steel mills, rubber plantations, and just about anything needed to make the components for the Model T. It was natural for him to look north, where he hunted with his cousin by marriage, to source his own wood. Kingsford was appointed Ford’s agent in the U.P. and placed in charge of the Michigan Iron, Land & Lumber Company, which Ford set up to oversee his Northern Michigan operations. That company was absorbed by Ford Motor Company in 1923.

Eventually, Ford owned as much as a half-million acres of mostly hardwood forests, including the entire town of Pequaming, where he and Clara, Mrs. Ford, had a 14-room “cottage” overlooking a bay on Lake Superior. Pequaming was also the location of a large Ford lumber mill, as was L’Anse, located a few miles south. On Ford land adjacent to Iron Mountain, the automaker built an even larger facility for processing the wood from those mills into the aforementioned components, which eventually employed as many as 7000 workers. In time, an assembly line was set up in the Iron Mountain facility for the production of the bodies for “woodie” station wagons. That was converted to manufacturing military gliders during WWII. Near the Ford facility, housing for workers was constructed, and the land and the Ford operations were eventually incorporated as the town of Kingsford, in honor of its founder.

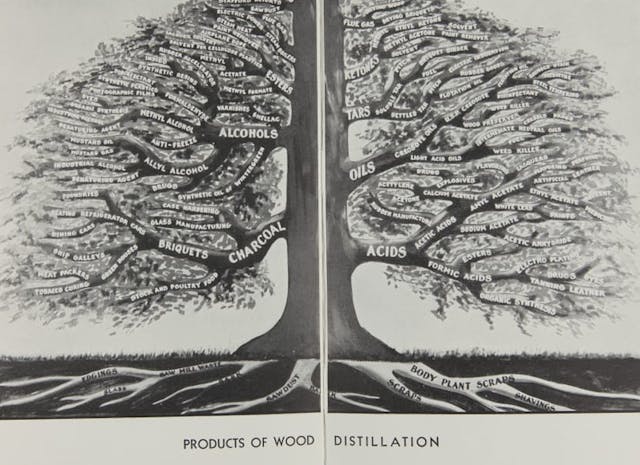

Henry Ford was a personally frugal man and his company reflected that. The millwork operations in Iron Mountain generated an enormous amount of waste wood and sawdust, up to 400 tons per day. While some of that was used to fire boilers operating in the facility, the Michigan Iron, Land & Lumber Co. built a five-story carbonization and distillation factory for extracting usable chemicals from the wood waste. Employing the Stafford-Badger wood distillation process, developed by Orin Stafford, a University of Oregon wood chemist, the plant produced tars, pitches, methyl alcohol antifreeze, ethyl acetate used in making faux leather for rooftops, and other alcohols used in paints.

When everything else was extracted from the wood, what was left was lump charcoal—about 100 tons of it per day. It could be used as a fuel, but there was a limited market. Enter the “charcoal briquette.” First patented in 1895 by W.P. Taggart, it was marketed as a “Lump of Fuel.” It wasn’t for backyard grilling but rather was sold as a safer, hotter, and more easily temperature-controlled alternative for wood stoves. An Ellsworth Zwoyer of Pennsylvania bought Taggart’s patent and set up the Zwoyer Fuel Company, with a couple of factories in upstate New York and Massachusetts, but he never managed to achieve national distribution, though regional and local competitors popularized the concept.

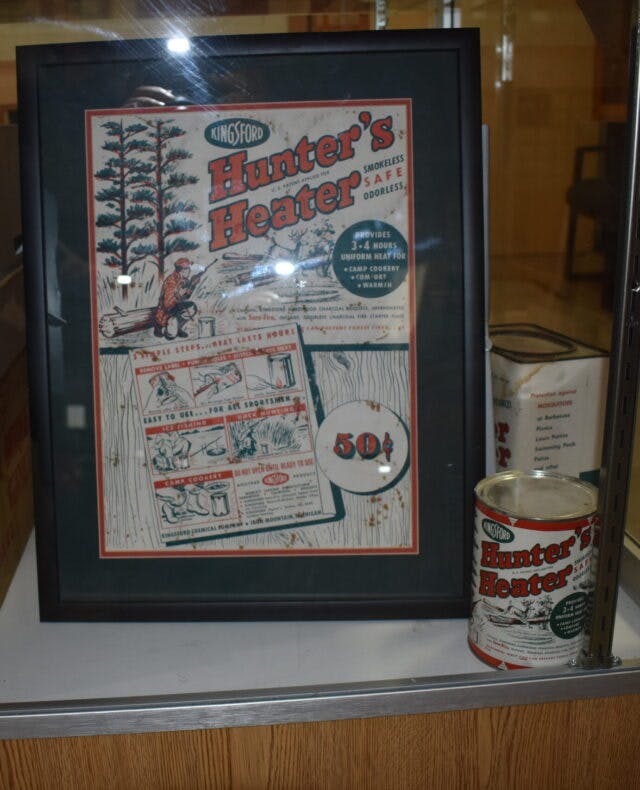

By the time Ford’s Iron Mountain operations were getting going, Orin Stafford had developed his own method for making “lumps of fuel,” joining powdered lump charcoal, tar, and starch under heat and pressure, creating what he called charcoal “briquettes.” Ford licensed the process, shortened the name to briquets and started selling them nationwide through Ford dealers. Though advertised as the “Fuel of a Hundred Uses,” the primary use of the briquets seems to have been what they are used for now, cooking food over a grill. In fact, alongside the bags of briquets, Ford also sold small grills in three sizes—for $1, $2, and $3 each—and complete “Picnic Kits.” Wooden excelsior was sold as fire starter. Ford also sold a “Hunter’s Heater,” essentially a quart can (as was used for motor oil) that was filled with briquet pieces. The idea was that you used a can opener to cut vents into it, lit the charcoal, and heated your general area with it, or cooked over it; no extra charge for the carbon monoxide.

After the end of World War II, American suburbs grew, a company named Weber introduced its own grills, and backyard barbecues became popular. In 1951, a group of investors bought Ford Charcoal and persuaded grocery chains to carry its products. Perhaps to distinguish the new company from Ford, the company was renamed Kingsford Chemical Company, in honor of E.G. Kingsford, although neither he nor his descendants apparently had anything to do with the business.

Both Edward and Minnie Kingsford died in 1943. The Iron Mountain charcoal briquet factory was closed in 1961, attributed to rising labor costs. Today the Kingsford brand is owned by the Clorox corporation and it continues to process about a million tons of scrap wood into charcoal briquets annually.

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Ford did overland camping trips that would be very daunting to most today, probably used the briquets? There was interesting photos at the Edison house in Florida, but it was years ago that I visited. I do recommend it though –the workshop was cool.

I’m not so sure Ford’s camping trips were so daunting. The “Vagabonds” as Ford, Thomas Edison & Harvey Firestone called themselves, brought along a truck full of supplies and a crew of workers to take care of things when Henry got tired of splitting wood for the camera crew that they also brought along. Info on Ford’s camping trips here:

https://www.hagerty.com/media/automotive-history/how-henry-ford-advocated-for-public-road-building-until-he-wanted-to-join-a-fancy-camping-club/

https://quizzclub.com/trivia/who-invented-and-patented-the-american-form-of-charcoal-briquette5a80c78a349f4cd89b09662a96bb2d31/answer/1925138/

Thanks for the link. The story there says that Zwoyer invented the charcoal briquet, but W.P. Taggart obtained a design patent on a “lump of fuel” in 1895 that looks pretty much identical to the shape of charcoal briquets. The sources that I found say that Ellsworth Zwoyer licensed that patent. Zwoyer’s earliest patent is from 1900 and is a process patent for a machine to make “artificial fuel”. His other patents are mostly for machines to making briquets. As mentioned in the article, the formula for making charcoal briquets as Ford made and Kingsford still makes, was developed by Orin Stafford, a University of Washington chemist.

What an interesting read. I’ve worked with manufacturing businesses whose processes involved by-products that generated a nice side revenue once they discovered there was a market for them. A good industrialist finds a way to use everything possible, minimize waste, and maximize profits.

A very good read on this history of the charcoal briquette. I did not know there was a direct Ford connection to it.

Ah, Ed Kingsford, another member of the delightful band of Henry’s vicious anti-Semites.

I didn’t come across any sources that indicated that Kingsford was anti-Semitic. It wasn’t like he was Ernest Leibold, the guy behind “The International Jew” in Ford’s newspaper, the Dearborn Independent. Not everyone in Henry’s circle was a Jew-hater. His son Edsel seems to have been a decent man and his grandson and namesake Henry Ford II was quite friendly to the Jewish community. The Deuce, met with David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, when he visited the U.S., and opened up an assembly plant to build Escorts in Nazareth.

Henry Ford wasn’t a Nazi or an exterminationist. He did business with Jews like Albert Kahn, his main architect, and sent every leading Detroit clergyman a Model T to use every year, including Leo Franklin, Ford was a farm boy with a farm boy’s fantasies and prejudices. He divided the Jewish world into “good Jews” the ones he knew, like Kahn, and the nefarious bankers of his fevered imagination.

I sometimes think Henry Ford was an idiot-savant. He was brilliant, but in a very limited range, but outside that range he was bat-guano nuts. A great man because of the way he changed the world, but not a good man.

I didn’t have a clue about the link between the town of Kingsford and the briquet until a few years ago. Drove a semi load of used tires to a building there to be shredded. Building at the time was being used by a waste hauler. The building was used back in the day for charcoal production