Media | Articles

Alberta, Michigan: Henry Ford’s Northwoods Fordlândia

You may have heard about Fordlândia, Henry Ford’s hubristic attempt to start a prefabricated company town and rubber plantation in the Amazon rainforest of Brazil to supply Ford Motor Company with rubber, getting around a British monopoly on natural rubber. Planned for 10,000 residents, construction on Fordlândia was begun in 1926. The town included American-style houses, a school, hospital, library, and hotel as well as recreational facilities including a swimming pool, a playground for children, and a golf course for the adults. Residents were expected to live their lives the way Henry Ford expected them to live.

The plan began with great fanfare with the Brazilian government granting the automaker approximately 5000 square miles of land for the project, but Mr. Ford abandoned his eponymous Brazilian town less than 10 years later in 1934.

While the notion of a “company town” today seems quaint, archaic, and even exploitative, they were not uncommon in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and Fordlândia was not Henry Ford’s only attempt to create a self-contained Ford community. Interestingly, he also located another Ford company town in another remote forest, far from the nearest city. It was, however, a bit closer to FoMoCo headquarters in Dearborn than Brazil. Alberta, Michigan, located northwest of Marquette in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, is about 500 miles from Detroit. Unlike Fordlândia, which became a ghost town, Ford’s Alberta operations continued for decades, and the small community that he built there still exists—as does the sawmill that Ford built there to employ the town’s residents.

It was natural for Henry Ford to look north for wood. Michigan is well known as the location of the Motor City, but less well known is the fact that Michigan was the leading U.S. producer of lumber from 1860 to 1910. By the turn of the 20th century, over 160 billion board-feet of lumber was harvested from Michigan forests. That’s a lot of White Pine. (I use the term harvested rather than logged because much of the state’s forest was clear-cut.) While northern Michigan is heavily forested today, with four national forests there is very little *old-growth timber left.

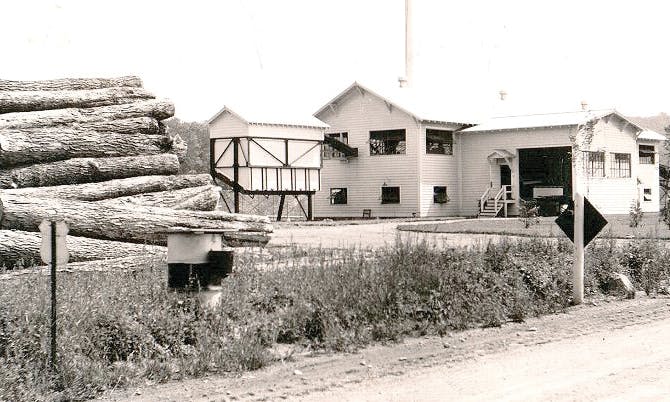

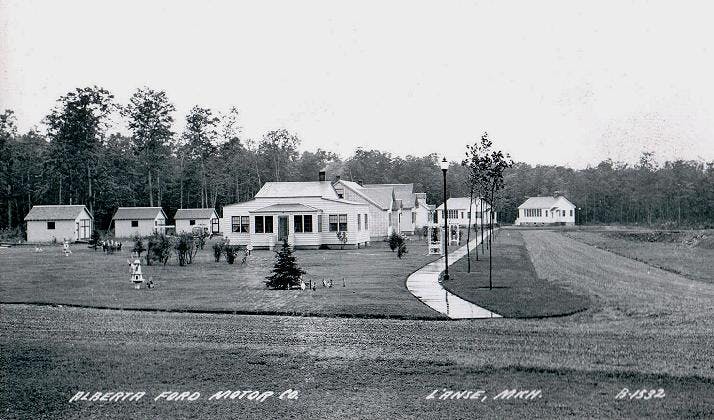

Ford had massive land holdings in the U.P. for his lumbering operations that supplied the wood needed to build Ford cars. It’s estimated that each Model T required about 100 board-feet of lumber in its production, and wood was also needed for “woodie” station wagon bodies, as well as crates for Ford-produced parts. To supply that lumber, Ford Motor Company had large, industrial-scale sawmills in Pequaming and L’Anse in the U.P. as well as a wood processing factory in Iron Mountain that employed as many as 7000 workers. The sawmill at Alberta, in contrast, was a much more modest operation, and the town was only planned for hundreds of people, not thousands, with lots platted out for just 70 homes, only 12 of which were completed. Also more modest than Fordlândia was the fact that Ford named Alberta not after himself but after the daughter of his head of northern Michigan operations.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

So why did Henry Ford build Alberta if he didn’t really need it’s lumber output? The answer is in the archives of Michigan Technological University, to which Ford Motor Company donated the mill and town in 1954 when production at the sawmill stopped. MTU continued to operate the sawmill as part of its forestry and lumbering programs and turned the town into a conference center. The archives of the town show that, like Fordlândia, it was as much a social experiment as it was an industrial operation. Alberta was part of Henry Ford’s “Village Industries” program. In the 1920s and ’30s, he set up about 30 small factories for making small parts and tools, mostly at mill and dam sites on rivers in small towns in Michigan (Ford was a fan of hydroelectric power, which he called “white coal”). Ford was a farm boy at heart and part of his idea was to provide seasonal employment for farmers so they would not be in financial risk of losing their farms.

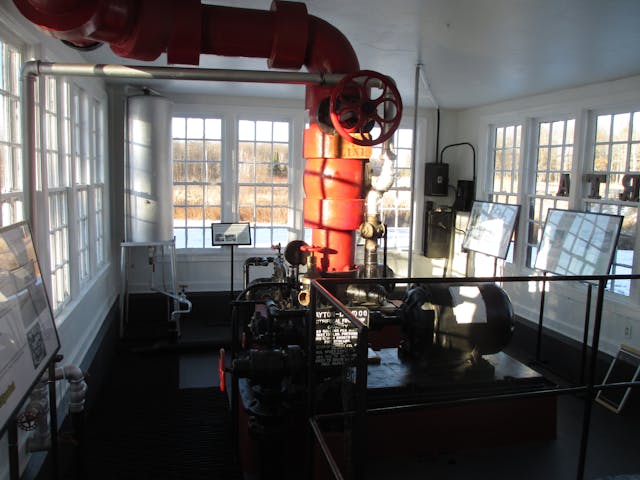

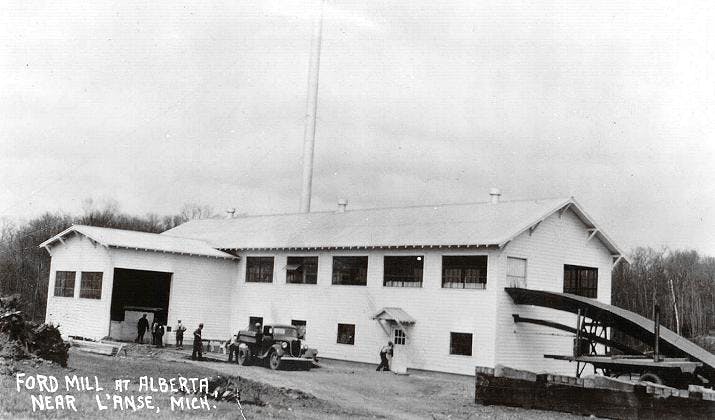

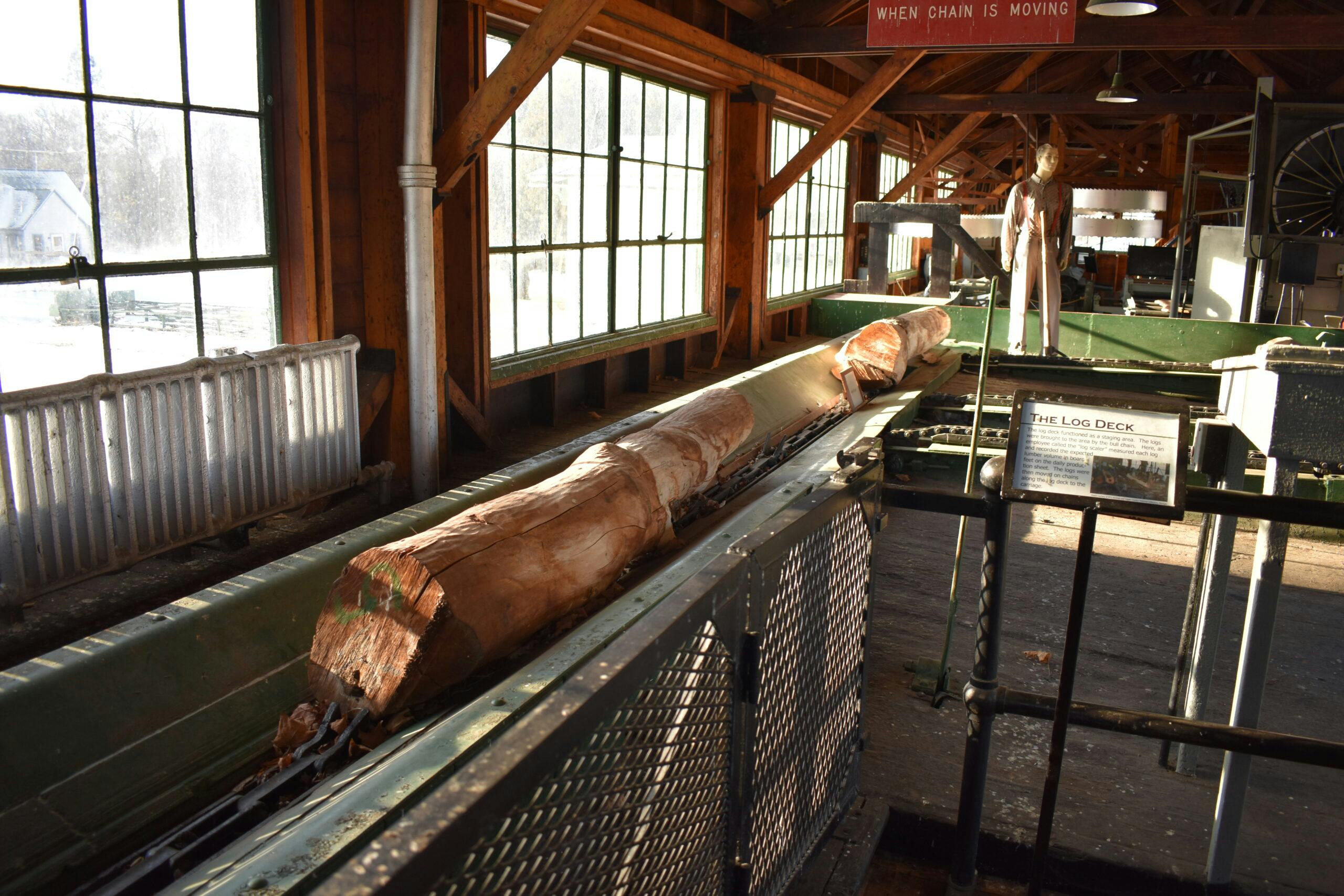

Unlike most of the Village Industries sites, which were often repurposed mills, Ford built Alberta from the ground up. He had the Plumbago Creek dammed to create a 20-acre lake for supplying the sawmill and town with water. A large metal sign with the Ford script logo still sits on the north bank of the lake, a waymark for northbound visitors on their way to the Huron Mountains or “copper country” in the Keweenaw Peninsula . The sawmill, pumphouse, and town were located on the other side of US-41. In addition to the town residents’ need for water, the pumphouse supplied water for the sawmill’s boilers (the mill originally ran on steam power but was later converted to electricity) and for the small, heated holding pond used to convey logs into the mill.

Coincidentally, the sawmill at Fordlândia is one of the few original structures there that still stands, so that’s another commonality between the two sites. Another similarity is that for someone who was raised on a farm, Henry Ford wasn’t very good at picking places to grow things, as you’ll learn below.

Unlike Fordlândia, however, Alberta is not a ghost town. All of the original structures are intact and the little town still has residents. Three-quarters of the homes that Ford built are long-term rentals, while the remaining four domiciles are used to house conference center visitors or lodgers looking for an alternative to hotels or Airbnbs.

The sources agree that Alberta was named after the daughter of the manager of Ford’s Upper Peninsula operations, but it’s not entirely clear if that was Frank Johnson, or his predecessor, Edward Kingsford, who built Ford’s large factory in Iron Mountain.

The sawmill started operations on September 1, 1936. When operating at full capacity, while modest compared to Ford’s other three U.P. sawmills, the Alberta mill could produce 14,000 board-feet-per-day of hardwood and more than 20,000 board-feet-per-day of softwood that was used in the manufacturing of Ford automobiles. However, the first lumber that was milled there didn’t go into making Ford cars but was rather used to build the first houses in Alberta. A small neighborhood was constructed, including sidewalks and streetlamps. Two small schoolhouses were also constructed.

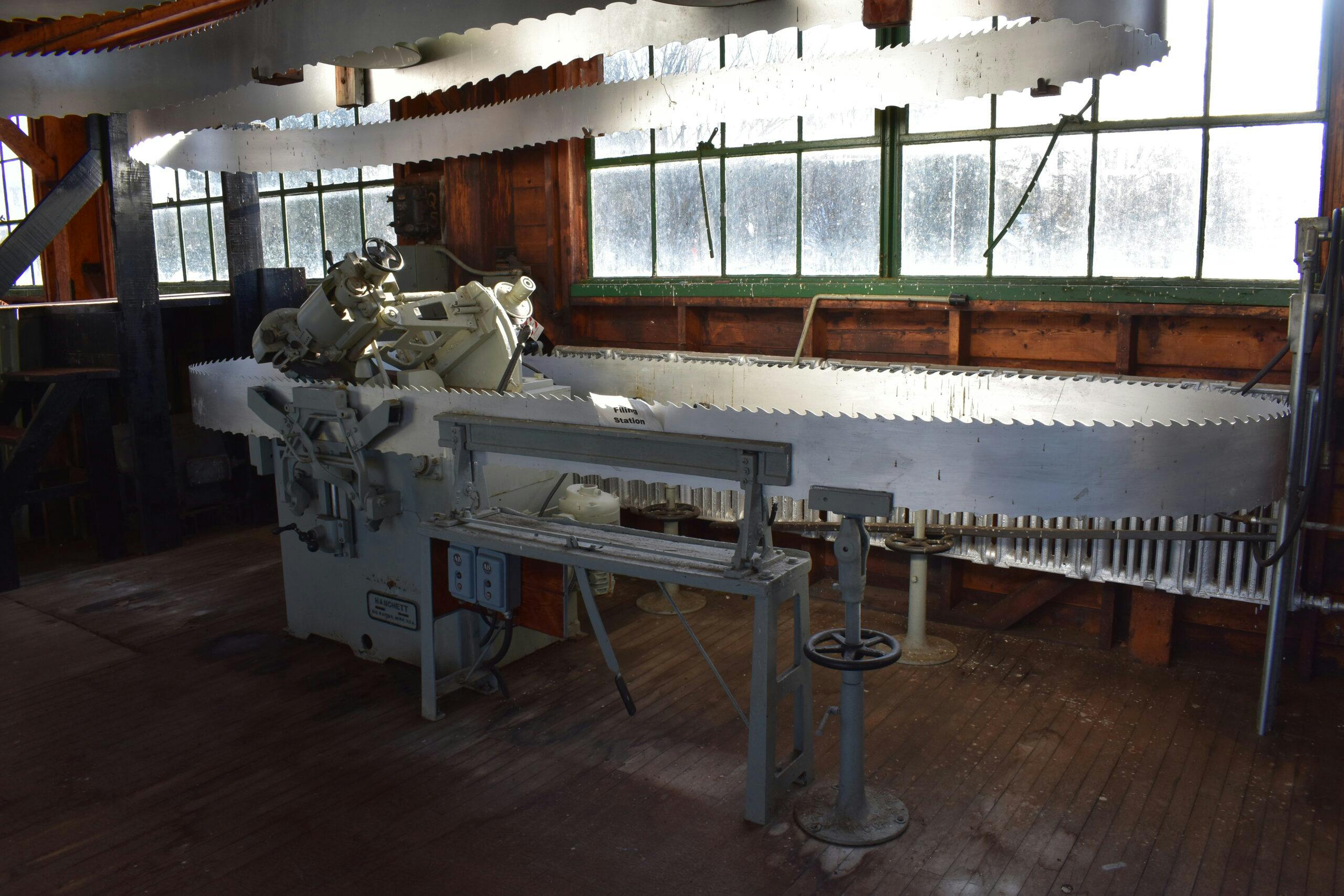

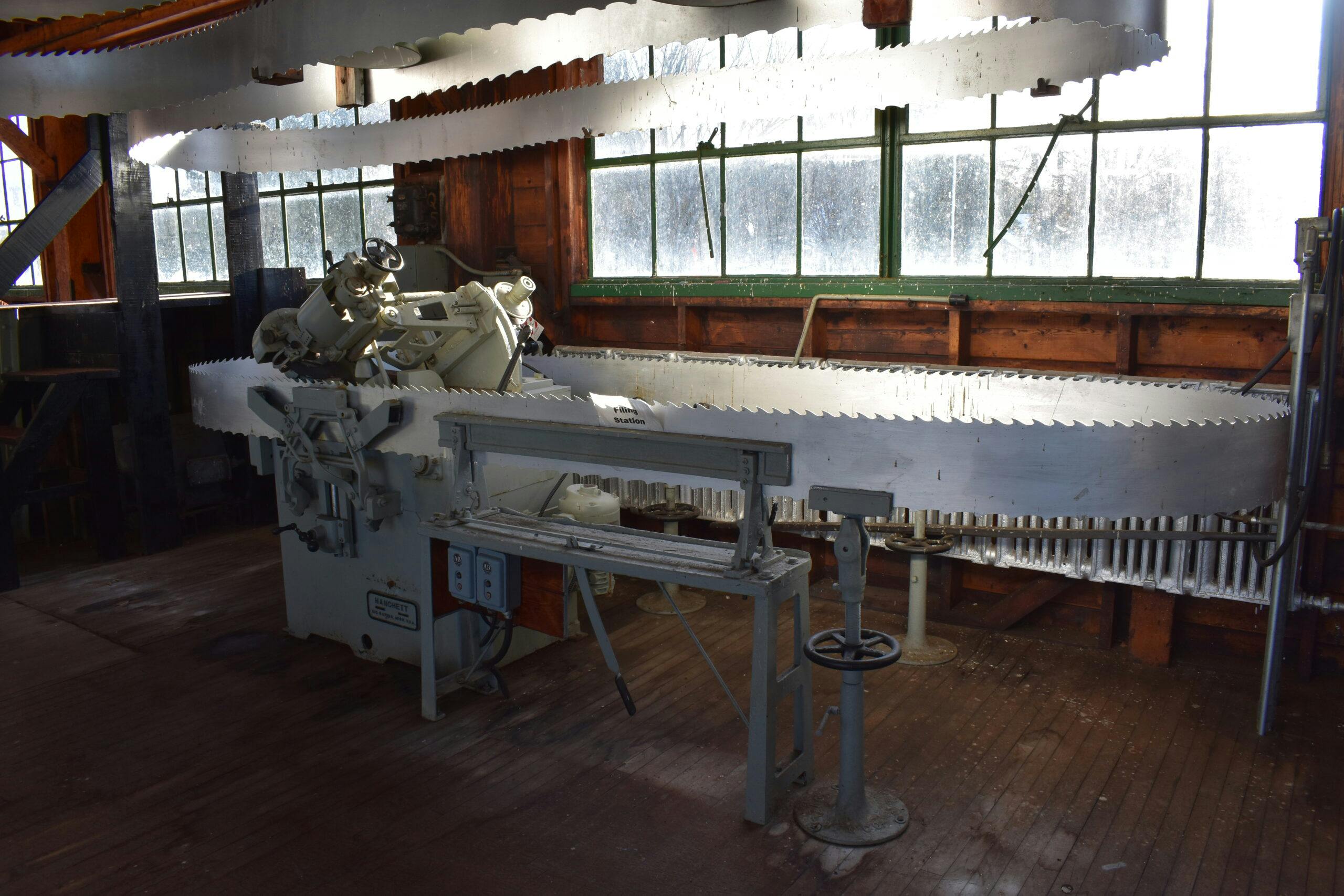

As with Ford’s other northern Michigan lumbering operations, the Alberta sawmill recycled. Bark, trimmings, and scrap wood were used to fire the boilers that heated the holding pond and originally provided steam power, and a clever gravity-fed system collected virtually all of the sawdust that was created, and a conveyor belt carried it from the mill’s basement to the boilers. That system not only kept the mills relatively clean, it also helped prevent fires from the highly flammable saw dust and powder.

Ford wanted Alberta to be a self-contained town, but it could never achieve that goal because it lacked the things that make a town. Oddly, for a company town, there were no stores, not even the kind of company-owned store that contributed to company towns’ exploitative reputation. Though they were likely planned, a church, bank, clinic, or post office never existed in Alberta either. Residents had to leave Alberta to buy basic goods, cash their paychecks, receive treatment from a doctor, or mail a letter.

Ford allocated some of his timberlands to the Alberta project. The idea was that each worker would have access to a 60-acre woodlot that they would log to supply the mill with timber, as well as a smaller two-acre plot for farming food. That way the workers would have the job security of winter logging, summer farming, and working in the mill. Henry also wanted the public to see a working mill and his ideal community. Period signs for the facility adjacent to US-41 say “Visitors Welcome.”

As with many of Henry Ford’s plans (like the backup diesel generators the Village Industries plants used when hydro power wasn’t sufficient) things didn’t work out as planned. It quickly became obvious that the mill workers could not produce enough logs from their woodlots to keep the mill operating all year, and Ford Motor Company started using outside suppliers and its own logging operations to feed the Alberta facility. As for farming, just as Fordlândia’s location wasn’t ideal for growing rubber, the Alberta area’s soil had trouble sustaining food production, and Northern Michigan’s huge deer population feasted on what little could be grown.

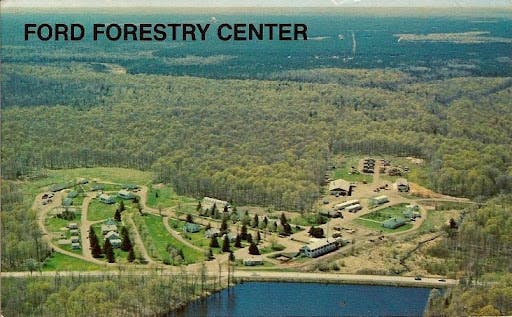

By the time domestic automobile production resumed in 1945, after the end of WWII, the use of wood in car production had plummeted. While Ford continued to build “woodie” station wagon bodies at Iron Mountain, the company had little need for the Alberta sawmill’s output. Also, Alberta’s patron, Henry Ford himself, passed away in 1947. As with other Village Industries sites, it was his pet project, and it didn’t really matter if it was profitable for Ford Motor Company or not—at least while he was still alive. By 1954, Alberta had lost both its need and its patron, and Ford closed the mill on June 30th of that year. Five months later, the Ford Motor Company deeded the sawmill, houses, schools, and over 1700 acres of forest to the Michigan College of Mining and Technology in Houghton, now Michigan Technological University. Michigan Tech renamed the site the Ford Forestry Center and built additional structures. Today, Alberta houses the school’s experimental research station, educational laboratory, learning center for MTU’s School of Forestry and Wood Products, and a small conference center. The sawmill continued to operate as a learning laboratory for decades.

In 1997, Ford Motor Company donated $100,000 to be used to restore the mill as a museum and interpretive center for the public, reviving one of Henry Ford’s original plans for the site. A consortium of MTU faculty and staff, retired Ford employees, and local sponsors started the restoration project and prepared exhibits, however because of possible liability and the state of the sawmill’s lighting, walkways, and electrical systems, the facility doesn’t meet current year standards for visitor safety and the museum is closed to the public.

Though Ford stopped operating the mill in 1954, Alberta, unlike Fordlândia, never became a ghost town. All of the original Ford structures are still intact and in use. While the museum is closed to the public, there is a gift shop with memorabilia available for purchase in the adjacent pumphouse.

The sawmill is also closed to the public, but Ford Center operations manager Jim Tolan graciously gave Hagerty access, along with a personal tour, so that we could collect photos and video.

In 2022, MTU announced that it was considering tearing down the old sawmill, as the building is starting to deteriorate from the elements. Though the main building with post-and-beam construction is still structurally sound, “good bones” as they say, there are a couple of leaks in the metal roof and it could use a sensitive restoration. Reopening the museum is probably not practical, as it would require substantial period-incorrect renovations to meet current standards for visitor safety but it would be a loss to history if the facility was demolished. Old industrial sites typically get redeveloped so there are very few still-extant pre-WWII factories whose buildings are in original condition, let alone still being fully functional with all machinery intact. Besides being an important artifact of general industrial history, the Ford Alberta Sawmill sits at the nexus of what have likely been the two most important industries in Michigan’s state history, lumber and automobiles.

The announcement about the possible demolition galvanized a coalition of activists, including students, faculty, and staff at MTU, area residents, and Michigan history buffs that so far has persuaded the university to put off any immediate plans to tear down the mill.

If you’d like to visit Alberta, it’s about 60 miles west of Marquette and about 70 miles north of Iron Mountain.

*If you’re in northern Michigan and you’d like to see some of the remaining old-growth forest that fed mills like Alberta’s, much of what remains has been preserved in state and national parklands and is accessible to visitors.

Guess it’s my mid-century Midwestern childhood, but I love that old architecture.

And that would be Kingsford, as in the charcoal briquets…which is a whole ‘nother story…

Yes, technically the Iron Mountain facility was in an unincorporated area adjacent to town that was later named Kingsford, after Henry Ford’s main man in the UP. We covered the charcoal briquets story here: https://www.hagerty.com/media/automotive-history/at-your-next-bbq-tip-your-chefs-toque-to-henry-ford-who-helped-popularize-charcoal-briquets/

This looks like a cool place to visit, but it sounds like it’s a little bit off the grid.

It sounds like a good idea but half-baked. It would be cool to see it in operation as a museum.

I knew about Ford’s Iron Mountain operation, but Alberta is a new one for me. Incidentally, Henry’s manager for operations in the UP, Edward Kingsford, should be a familiar name if you barbeque….yep, that’s the charcoal briquette company that was started to use some of the scrap left from Ford’s lumbering/milling operations. Old Henry didn’t waste a thing! Some of us are old enough to remember those Kingsford charcoal bags contained actual scraps of charcoaled wood, not pressed briquettes as we have today.

https://www.hagerty.com/media/automotive-history/at-your-next-bbq-tip-your-chefs-toque-to-henry-ford-who-helped-popularize-charcoal-briquets/

I would like to speak with the author. I live in Santarém. Ford’s company arrived here in 1928, and after that fordlandia. I believe the author knows that, but that happens sometimes.

The Brazilian operation is covered in “Fordlandia, The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City” by Greg Grandin, copyright 2009.

The nanny state strikes yet again. Preserving history and modern day “safety” standards rarely line up. Just have anyone that visits sign a waiver saying they assume all responsibility for any sort of mishap that can happen when going to someplace like this. Problem solved. People get to enjoy what was.

I was at the Ford Center in the summer of 2023 for a climate change symposium. It was and is a magical place, with so much original equipment in place that it’s easy to imagine a century washing away and the place struggling along in its heyday. Off the beaten path, yes, but well worth it.

I hear the mill could be rehabbed for about a million dollars. Who reading this has connections to a foundation or some such that could make that happen? Must be someone.