Media | Articles

After 45 years, Alvis is recreating its cars using original blueprints

Most entrepreneurs who dabble in the de-mummification of long-dead car brands abide by an unwritten law: Every company that returns to life must specialize in high-end luxury vehicles with multi-million-dollar price tags and electric powertrains. England-based Alvis is an exception to that rule.

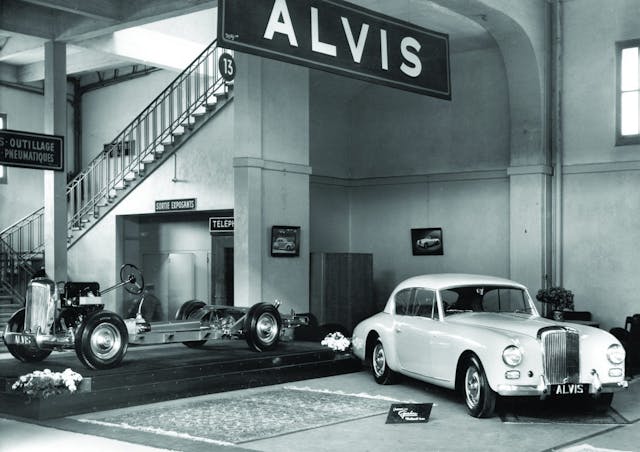

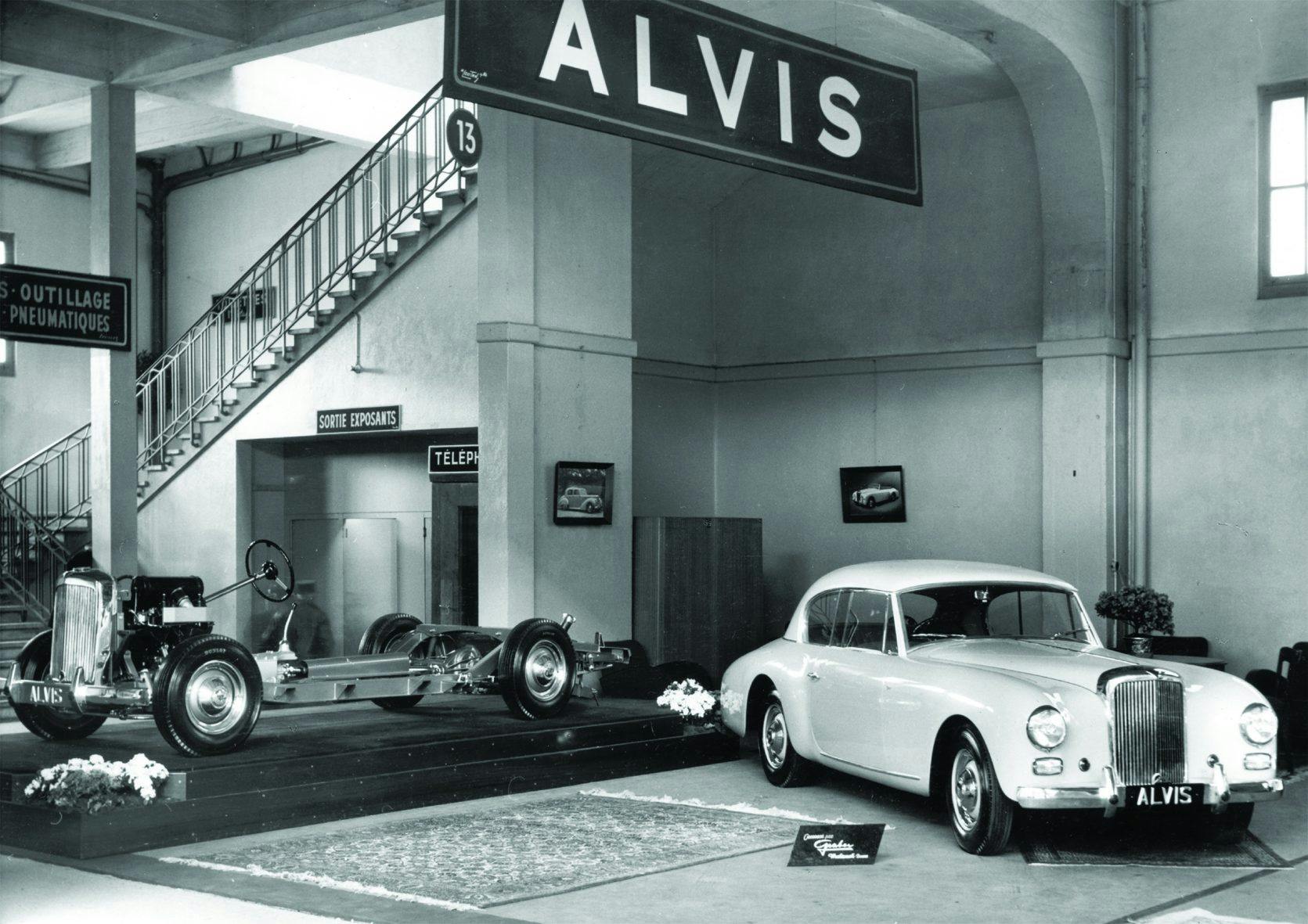

In its heyday, Alvis peddled some of the quickest, most innovative cars ever to turn a wheel on British pavement. Most notably, it offered front-wheel drive and a supercharged engine in the late 1920s. The company shut down unceremoniously in 1967, and Alan Stote resurrected it to make the same cars the brand offered when it was alive. He’s using decades-old blueprints and, when possible, original parts.

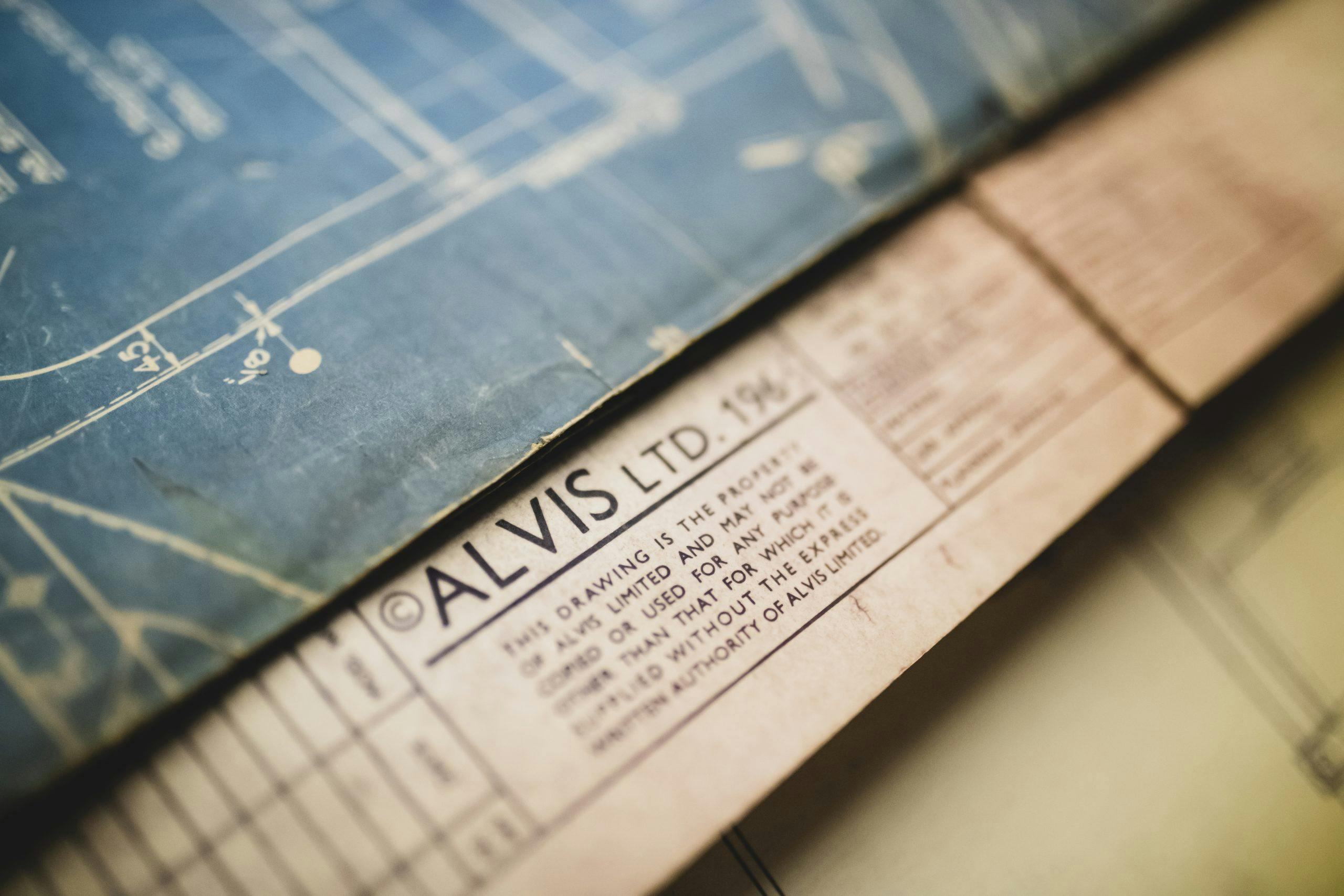

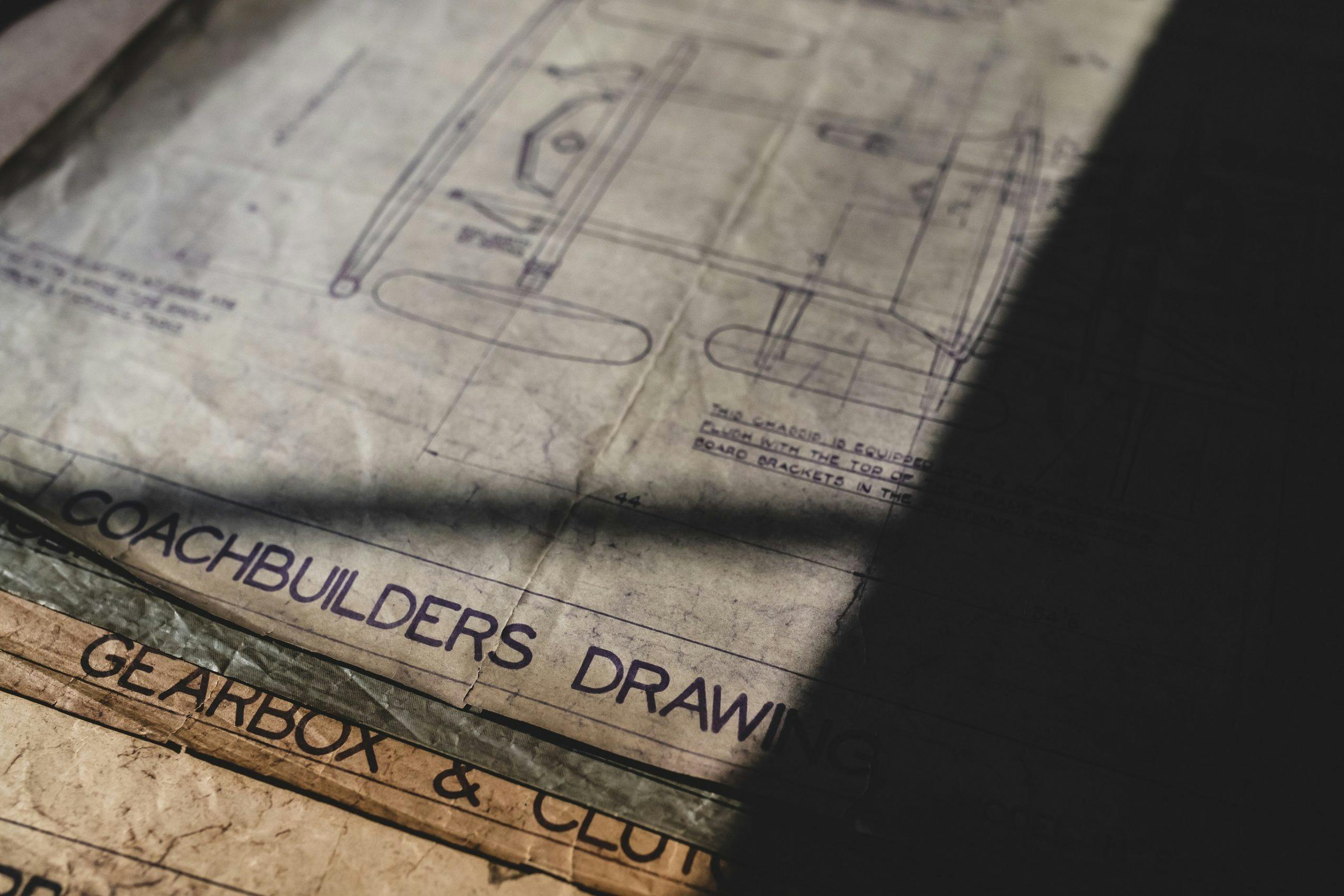

“Alvis was great at record-keeping. It had a very large drawing office. For every car it made, it produced a detailed sheet of every component that went into it. We have all of these in our archives,” Stote tells me, his voice brimming with pride. He has access to 20,000 original drawings, plus a huge stock of neatly-organized original parts built as spares decades ago and never used. In 2012, he saw this mass of heritage as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to build a limited number of continuation cars.

Customers can choose whether to begin a build with a donor car (either one they already own or one supplied by Alvis) or to start from scratch. Existing vehicles keep their original registration date; new builds are titled in the year they’re finished. From there, enthusiasts have many à la carte options to choose from, including different body styles, paint colors, and upholstery types. Some models are recreations of prewar cars, like the Vanden Plas, while others are rooted in the 1960s, like the Graber.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Alvis needed to make a few concessions in the name of safety and emissions regulations. Its modern-day builds gain a collapsible steering column, seat belts, disc brakes, and fuel injection, though fitting the last feature didn’t require altering the engine. It was simply a matter of designing the system. “When we finish the car, you can’t really distinguish any of those features,” Stote points out. The customization largely ends there; customers can’t request a Bertelli coupe powered by a 1000-horsepower Hellephant engine, though Alvis is open to the idea of fitting modern creature comforts like air conditioning.

Recreations of cars made before WWII use a 4.4-liter straight-six; newer models are fitted with a 3.0-liter straight-six. Both engines are emissions-compliant in the United Kingdom.

The amount of original parts used in each build depends on the car. Broadly speaking, the older the car is, the less likely Alvis is to have parts for it. “In the 1960s, there weren’t many components left in stock that would have fitted cars from the 1920s and the 1930s,” Stote explains, adding that decades of supplying parts to Alvis owners around the world also depleted the supply. Parts that fit cars designed in the 1960s are easier to come by. “There are substantial quantities of post-war parts for the three-liter cars.”

The firm doesn’t have a foundry, so it relies on outside companies to manufacture parts when needed. It makes the bodies in-house, however. That arrangement is the exact opposite of how Alvis once operated; it used to make its own mechanical parts and source bodies from coachbuilders in England and abroad. Every car is hand-assembled from start to finish, a process that requires up to 5000 hours of labor and can take up to two years depending on the body selected and the options added by the buyer. Customers are invited to participate in the building process by dropping by the workshop to check on their car-to-be.

Alvis only builds to order; it doesn’t want to amass an inventory of unsold cars. It’s currently working on its seventh and eighth continuation cars, and it has three additional orders to fill after it finishes them, which is enough work to see it through 2023. Pricing starts at about 250,000 British pounds, a sum that converts to approximately $312,000, but the final figure varies greatly depending on the configuration.

At this rate, it will take some time before Alvis runs out of original parts. When it does, engineers will dive into its vast archives, find the blueprint that corresponds to the missing component, and build it. Stote is happy with the company’s current two-chassis range, and he’s not planning on following the path blazed by Morgan, which used its illustrious heritage as a foundation on which to build a full range of cars.

“There’s no need to design our own idea of an Alvis. Numerous coachbuilders made bodies for Alvis over the years, so there’s a wide catalog to choose from. That’s the legacy it left us,” Stote concludes.

It currently distributes cars in Europe and in Asia. The American market is on its radar, too, but Alvis first needs to find and train a local agent capable of handling distribution and aftersales support.