Media | Articles

11 eclectic vehicles celebrating Saab and Volvo history

Though the name Saab has been unceremoniously confined to the automotive attic, its heritage lives on at the brand’s official museum in Trollhättan, Sweden. Run by knowledgeable, dyed-in-the-wool enthusiasts, including a few that worked for the brand in its heyday, it’s home to dozens of prototypes, concepts, race cars, and regular-production models that tell the Saab story from start to finish.

We’re lucky (and thankful) that it still exists; liquidators planned to close the museum and sell off the collection one piece at a time to satisfy creditors after the carmaker’s bankruptcy in 2012. The city, the Saab AB defense company, and the Marcus and Amalia Wallenberg Memorial Trust all stepped in to save it.

Volvo’s official museum in nearby Gothenburg is inevitably bigger than Saab’s for a couple of reasons. First, it’s better funded, because the brand whose heritage it showcases still survives. Second, Volvo simply has more chapters in its story; Volvo released its first production car, the ÖV4, 22 years before its Swedish rival.

Walking through the Saab Car Museum feels like taking a stroll through a history book written for car geeks, while the Volvo Museum has a family-friendly flair to it. Both are equally fascinating, because Saab and Volvo share an openness that’s unusual in the automotive industry. If a model exceeded sales expectations, it’s in the museum. If it sold poorly, there’s a spot for it, too. Neither brand is ashamed to shine light on its past for enthusiasts willing (and able) to make the trip.

While most travel plans are on hold across the globe, here are 11 of the most intriguing cars—and one boat—from both museums. They may just inspire you to add another destination to that post-pandemic bucket-list …

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

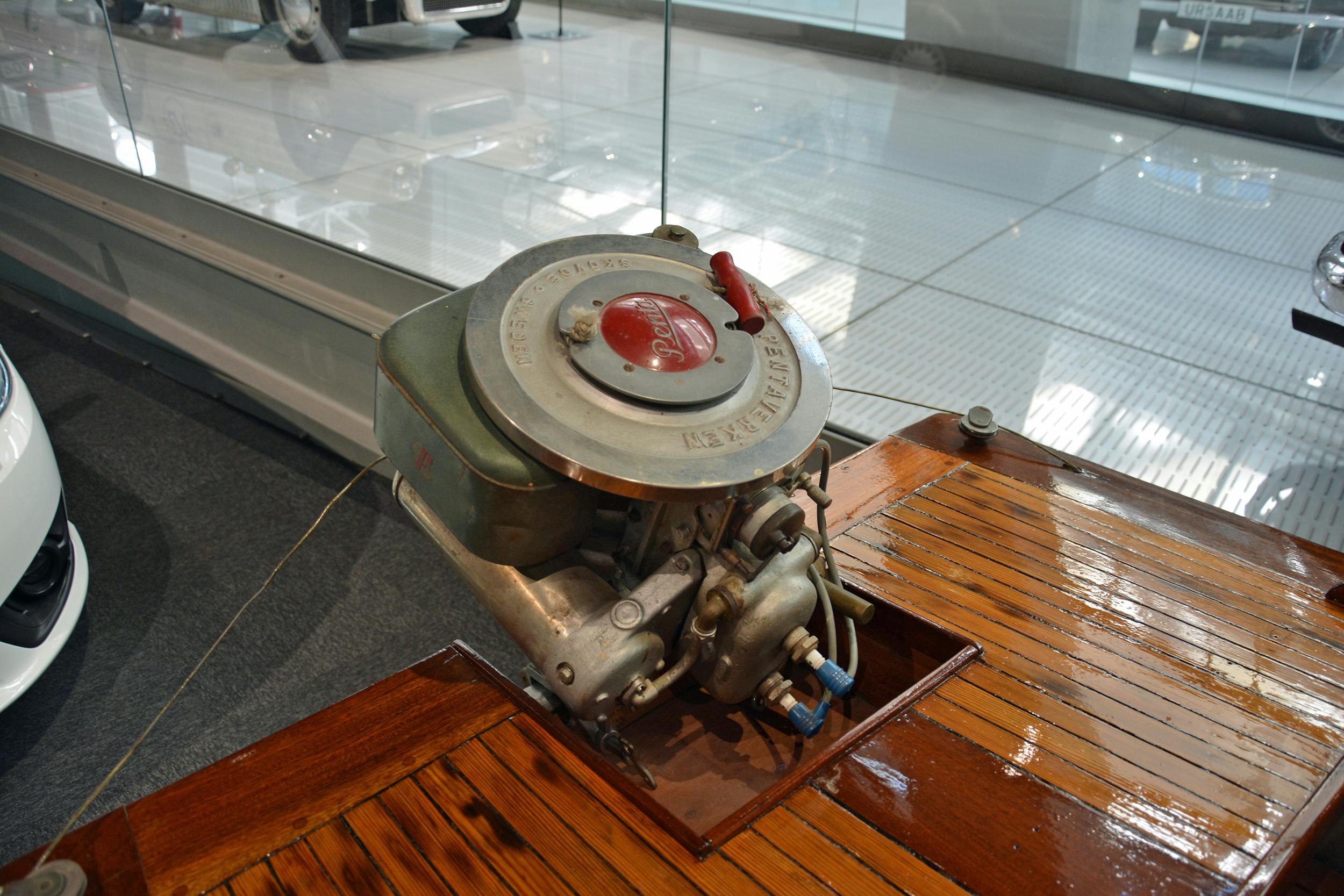

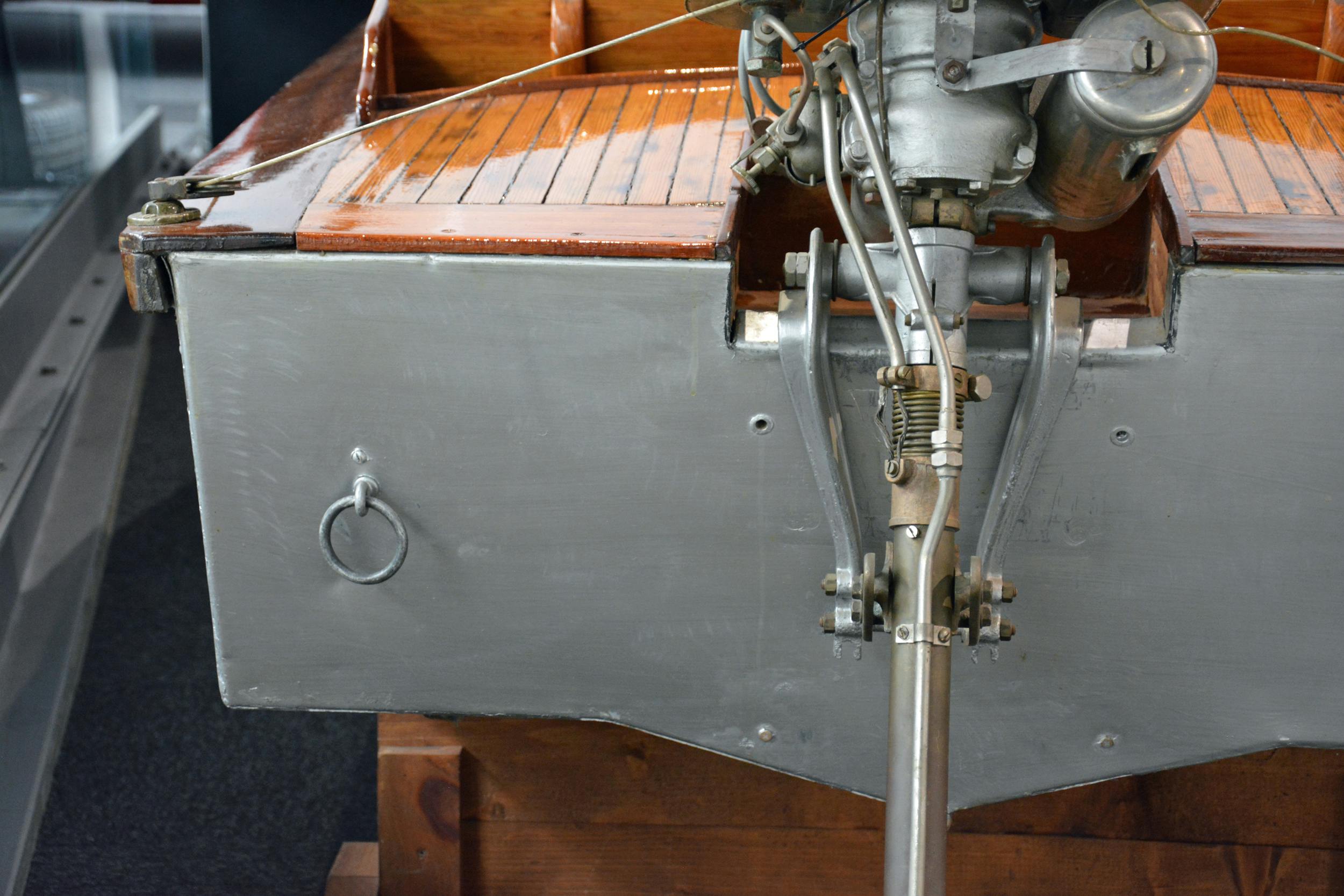

1947 Saab Bruksbåt

When demand for aircraft plummeted after World War II, Saab desperately sought to enter other sectors of the transportation industry to keep its factory open and avoid laying off workers. The beleaguered company concluded it could easily apply plane-building techniques to boat manufacturing. Demand was theoretically there; Sweden has thousands of miles of coastline and a countryside dotted with picturesque lakes.

Built in 1947, the model shown here is called Bruksbåt, which indicates it’s a utility boat aimed largely at professional users. The hull is made with riveted aluminum, just like a plane’s fuselage, and its deck is lined with wood. (Saab likely outsourced the woodwork to a local company.) Power came from an air-cooled, two-cylinder outboard engine sourced, somewhat ironically, from Volvo’s Penta division.

Saab’s boats were absolutely lovely to look at but less enjoyable to take on the water—partly because they were prone to corrosion. The company learned building a boat like a plane wasn’t as straightforward as it had first appeared. Saab made about 250 boats of various sizes before calling it quits to focus on cars.

The example pictured here, named Saalina, has been treated to a full restoration. Notably, the steering wheel is not the original unit.

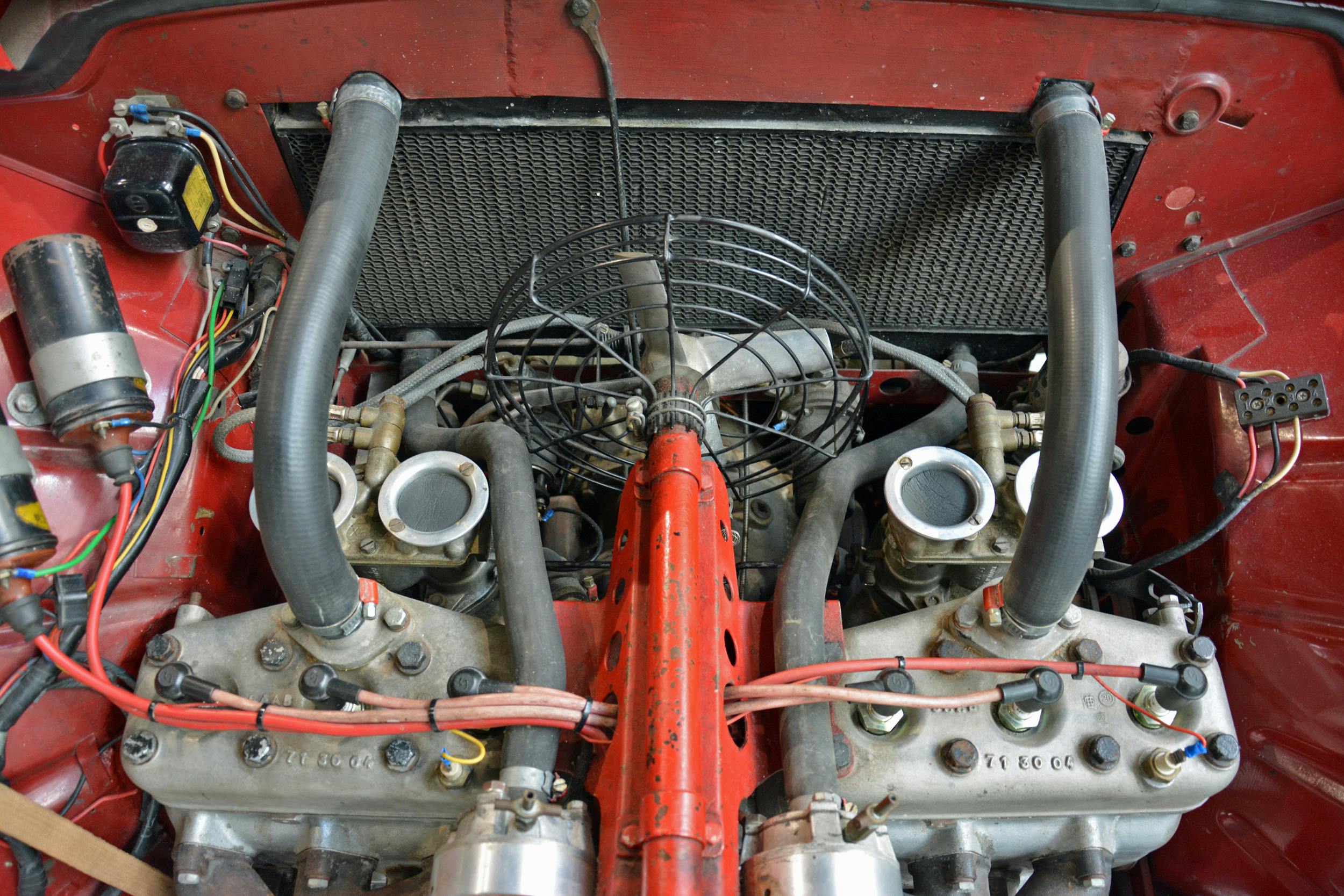

1959 Saab 93 Monster

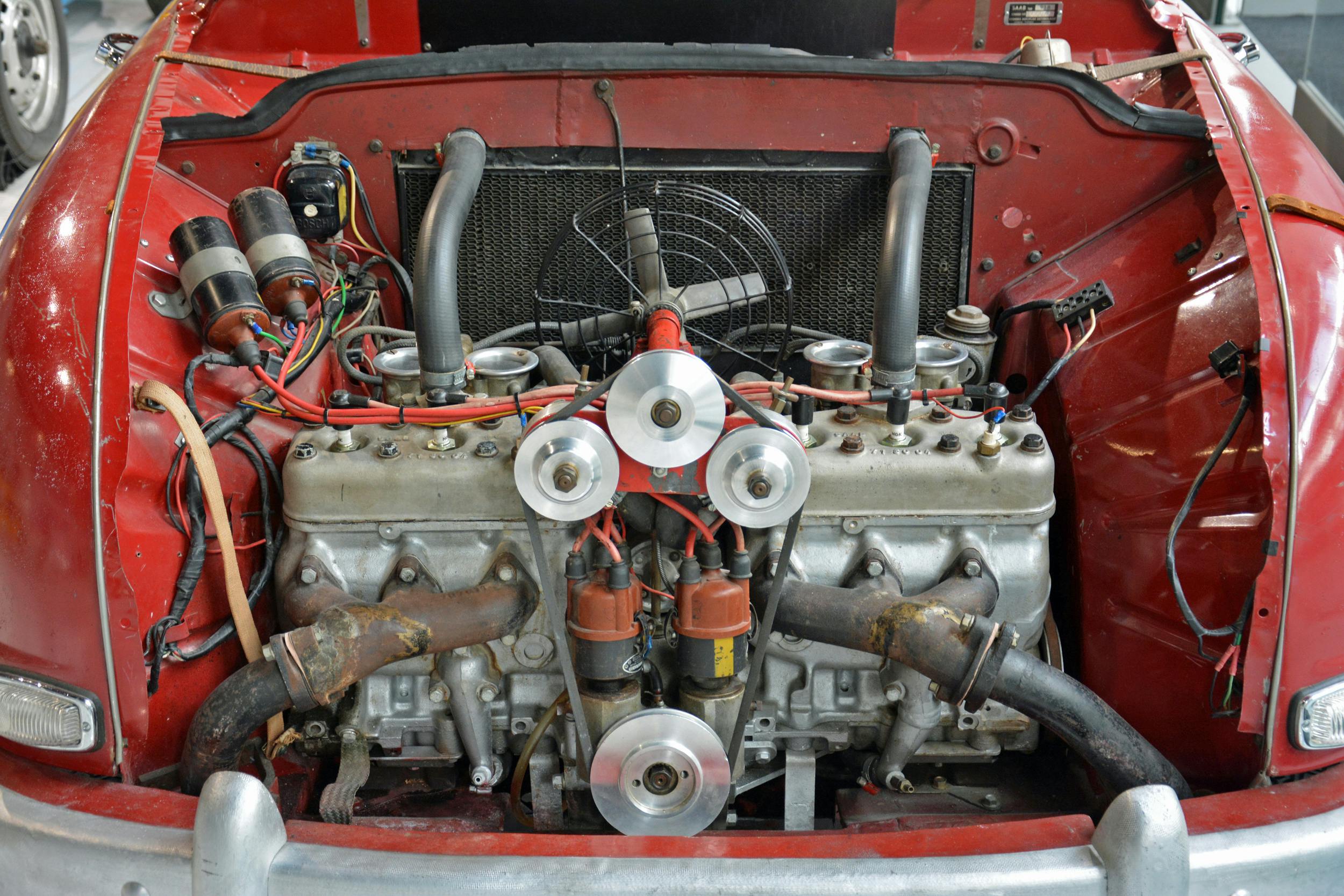

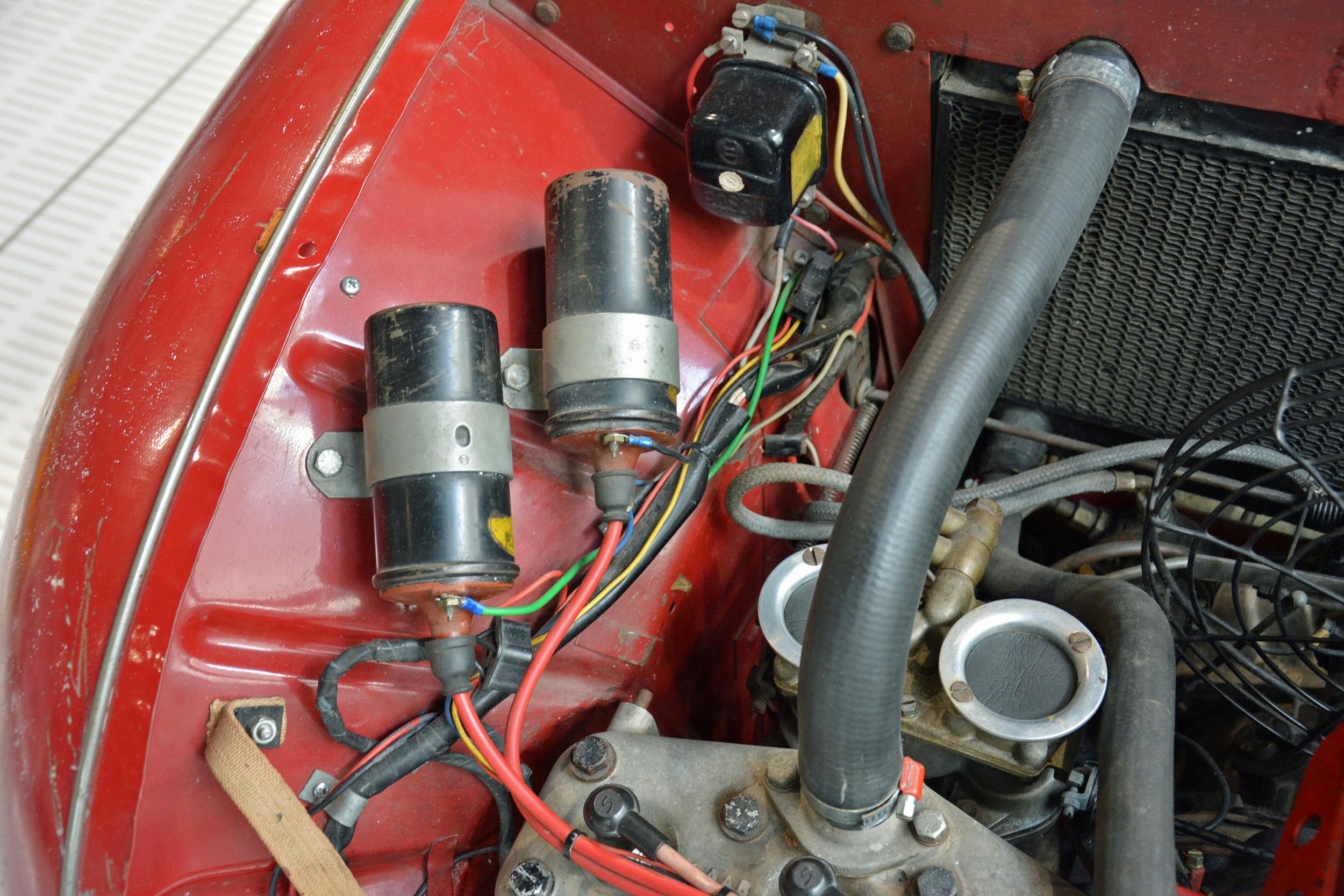

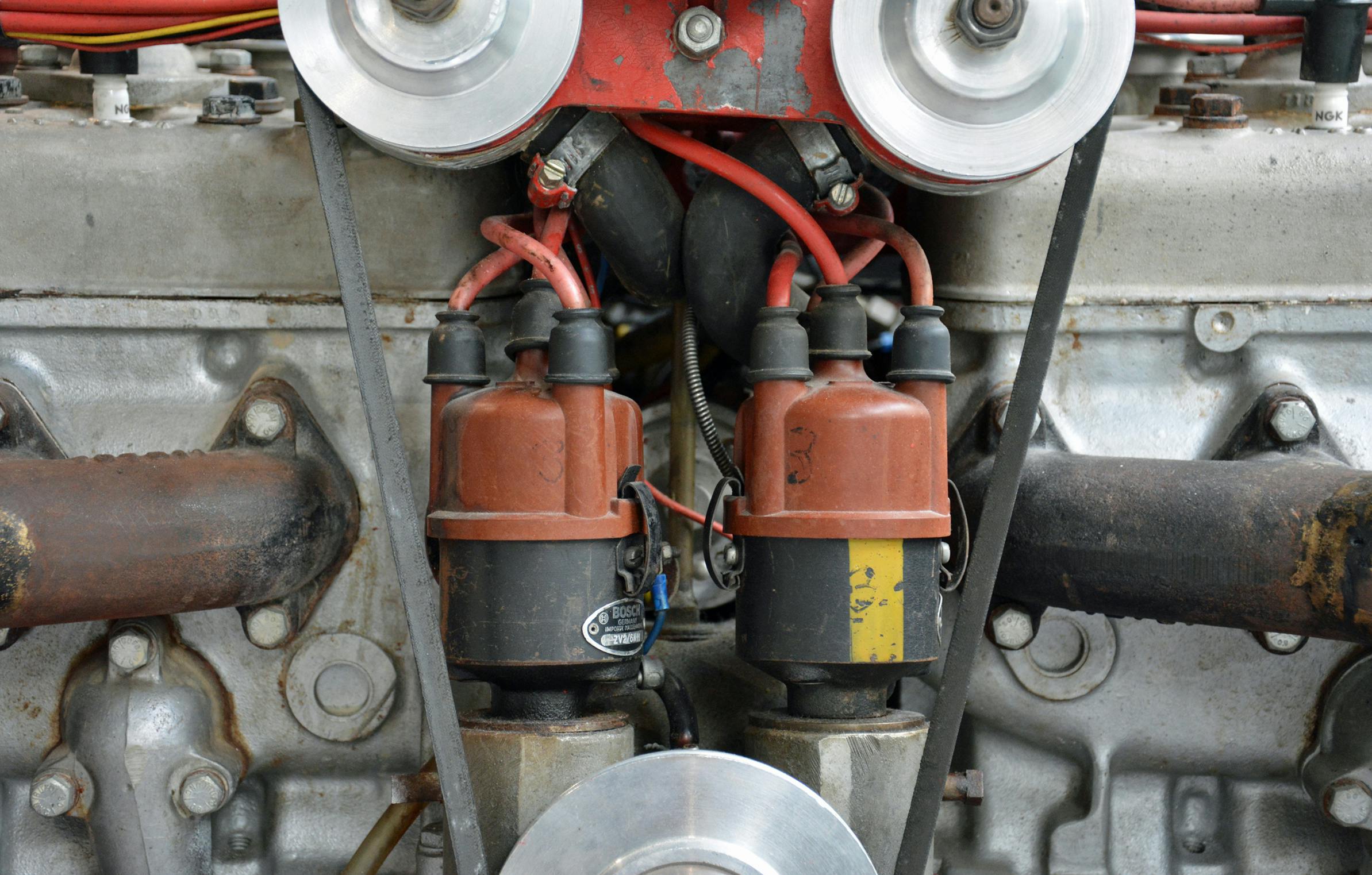

In 1959, motorsports-obsessed Saab wanted to build a more powerful race car without starting from scratch. Engineers took a 1959 Saab 93, the only model Saab made at the time, and began by stripping almost every part of the interior to save weight. That was the easy part; figuring out what engine to use was far more difficult. The only one in its stable was the three-cylinder, two-stroke unit that every 93 came with. Executives weren’t opposed to sourcing an engine from another automaker, but they ultimately decided to keep the design in-house so engineers fused a pair of triples to create a straight-six.

The end result was a 1.5-liter six-cylinder mounted transversely (and rather snugly) between the 93’s front wheels. It used two coils, two distributors, two double-barrel carburetors, two side-exit exhaust systems, and two water pumps connected to a single radiator installed right in front of the firewall. The engine made 138 hp—a considerable increase over the standard 93’s 38-horse output—and spun the front wheels via a column-shifted four-speed manual transmission.

Saab called the 122-mph prototype Monstret (or Monster) and promptly put the car through its paces in the Swedish countryside. It must have sounded like a chorus of six wailing leaf blowers. Historians disagree about Saab’s reasons for canceling the Monster project. Some argue the company wasn’t able to convince a sanctioning body to allow a 93 with such a Frankensteined engine. Others claim the powertrain was far too complicated to fine-tune; it was infamous for creating a massive amount of torque steer and destroying transmission pinions. In hindsight, it’s probably that both sides are partially correct. In any case, Saab continued racing with tamer cars, and its need for speed led it to experiment with turbocharging.

1974 Saab 98

Saab built the 98 prototype in 1974 as it experimented with the idea of applying the Combi Coupe treatment to the 96. From the tip of the front bumper to the B pillars, the 98 looked just like the two-door sedan on which it was based. Beyond that, its roof line gently sloped into a generously-sized hatch that was more upright than the 99’s but far less utilitarian-looking than the 95 wagon’s. It also gained one-piece rear side windows—had the 98 reached produced, this feature would certainly have delighted back-seat passengers.

There were no mechanical changes; everything under the hood, including the Ford-derived V-4 engine, came from the 96. It was the same story inside, where the 98 even wore a 96 emblem on its dashboard.

Adding a hatchback like the 98 to the Saab range would have been relatively cost-efficient, and the 98 would have slotted neatly between the 96 and the 95 (though not numerically). However, executives axed it because they didn’t think enough motorists would buy it. Odds are they were also hesitant to invest any money into a new variant of a car that was originally launched in 1960 and whose days were evidently numbered—especially considering Saab was already beginning to prepare the 99’s successor.

1980 Saab 96 V4

Saab’s aging 96 carried on alongside the far more modern 99 for 12 years as a cheaper entry-level model. It finally retired in 1980, 20 years after its introduction, but its basic design traced its roots to the 92—the company’s first car, released in 1949. You can recognize late-model examples of the 96 were recognizable by their big plastic bumpers on both ends, larger front turn signals compared to earlier cars, and square headlights framed by a plastic grille. Saab also redesigned the rear lights, and some variants came with a plastic spoiler right above the rear license plate. Buyers could order the soccer-ball-style alloys, too.

Finland-based Saab-Valmet built the final 96 (pictured) on January 8, 1980. Shortly after rolling off the assembly line, it received a sticker to identify it as number 730,607 and the final 92-derived car. Race car driver Erik Carlsson drove it over 450 miles from the Finnish city of Nystad to Saab’s museum in its hometown of Trollhättan—a trek that included a trip on a ferry—with a journalist. It’s still there today.

1985 Saab EV-1

Don’t let the name fool you: the Saab EV-1 was in no way related to the battery-powered coupe General Motors aborted in 1999. Saab’s EV-1 wasn’t even electric. The Experimental Vehicle #1 concept made its debut at the 1985 Frankfurt Motor Show as a rolling demonstration of Saab’s latest innovations. It showcased the advancements the company planned to put into its cars as it looked towards the 1990s.

The sleek, wedge-shaped body hid a platform sourced from the 900. Though it retained the quirky hatchback’s turbocharged, 2.0-liter four-cylinder engine, Saab gave the four-pot a generous bump to 285 horsepower. Saab quoted a 5.7-second sprint from 0–60 mph—putting the EV-1 four-tenths of a second behind a Porsche 911 Carrera—and an impressive 168-mph top speed.

The EV-1’s front and rear ends were made using a bump-resistant Kevlar-aramid composite. Its doors were manufactured with a blend of fiberglass and carbon fiber—especially exotic in the 1980s, when you rarely saw carbon fiber outside a race track. The greenhouse was almost fully transparent, so a solar panel integrated into the roof powered the climate control system to keep the four-seater cabin comfortably cool—even if the coupe remained parked in the scorching sun for hours on end. On paper and in person, the EV-1 stood out as the most exotic car Saab had ever shown to the public.

It’s not difficult to imagine a car like the EV-1 positioned as the Sonett’s spiritual successor and pegged at the top of the Saab range. However, there’s no indication it was ever a candidate for production.

1987 Saab 900 T16 Rallycross

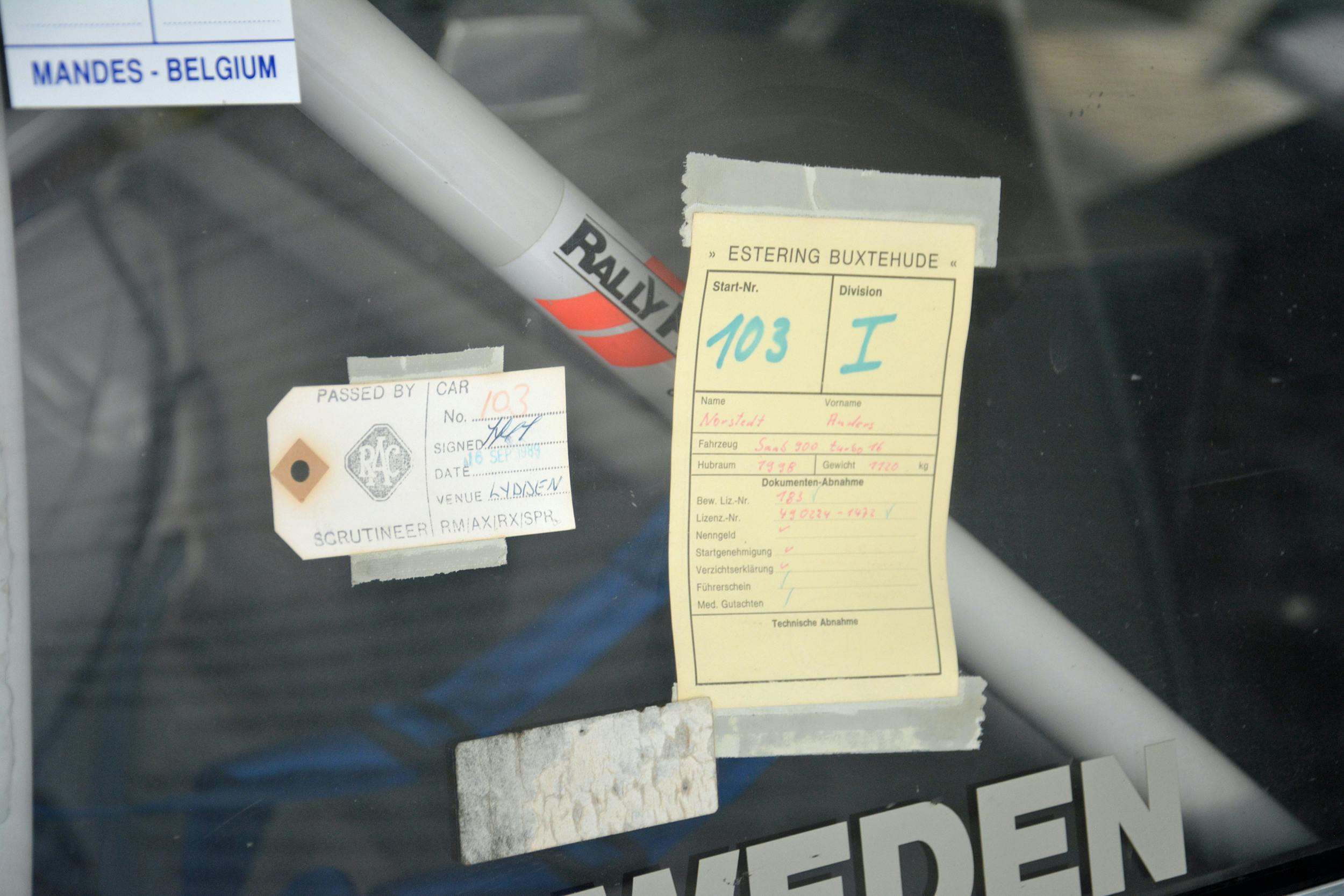

Saab’s best-known rally cars are the 96, which won the Monte-Carlo twice in the hands of Erik Carlsson, and the 99, driven to victory in the Swedish Rally in 1977 and 1979 by Stig Blomqvist. The 900 is better remembered as a high-performance family car, but it brought home its fair share of trophies, too. Anders Norstedt, a fireman from the town of Uppsala, won the European Rallycross championship in a modified 900 in 1984, ’85, and ’86. The car shown here is the T16 Norstedt raced in the series in 1987.

The 99 taught Saab much about building victorious rally cars, and the 900 was closely related to it; Norstedt and his team drew on that experience to convert a quick, spacious commuter into a serious racer. The team stripped the 900 of its lights and most of its interior to minimize weight. Its 16-valve, 2.0-liter four-cylinder engine was turbocharged to 230 hp (55 more than stock) and bolted to a close-ratio, four-speed manual transmission. (Curiously, the standard car’s five-speed-labeled shift knob remained.) The cavalry traveled through a limited-slip differential before reaching the front wheels. Norstedt also added fender flares, alloy wheels provided by Ronal, and additional gauges in the cabin.

While this proven formula worked wonderfully for years, Norstedt’s winning streak was broken by a similarly-modified Volvo 240 Turbo driven by Per-Ove Davidsson. He finished third in 1987 and ’88.

1956 Volvo Sport

The little-known 1956 Sport is an immensely significant milestone in Volvo’s history. The Sport is the company’s first sports car and the svelte coupe laid the groundwork for the P1800 released five years later. It’s also Volvo’s first, last, and only car with a fiberglass body. Then-CEO Assar Gabrielsson commissioned its development after taking a trip to the United States in 1953, likely inspired by cars like the Chevrolet Corvette. California-based Glasspar designed the body and taught Volvo how to build it.

Volvo sat the trim fiberglass body on a tubular steel frame and ensured that the Sport would live up to its name with a 1.4-liter four-cylinder, which sent 70 horsepower to the rear wheels via a three-speed manual transmission. The Sport weighed just 2292 pounds and could reach almost 100 mph, an impressive figure at the time. That’s a blast in the Nevada desert, but it’s probably terrifying on roads that meander through elk-infested forests.

Head-turning design and admirable performance numbers weren’t enough—the Sport completely flopped. Volvo managed to sell only 67 examples in 1956 and ’57, according to its archives. The fiberglass body made it immensely expensive to build and Swedish enthusiasts regularly surrounded by snow weren’t interested in a two-seater roadster; a coupe would have sold better because it would have kept its occupants warm and dry year-round.

If you’ve ever wondered why the gorgeous P1800 was never offered as a convertible from the factory, the ill-fated Sport is the answer.

1972 Volvo VESC

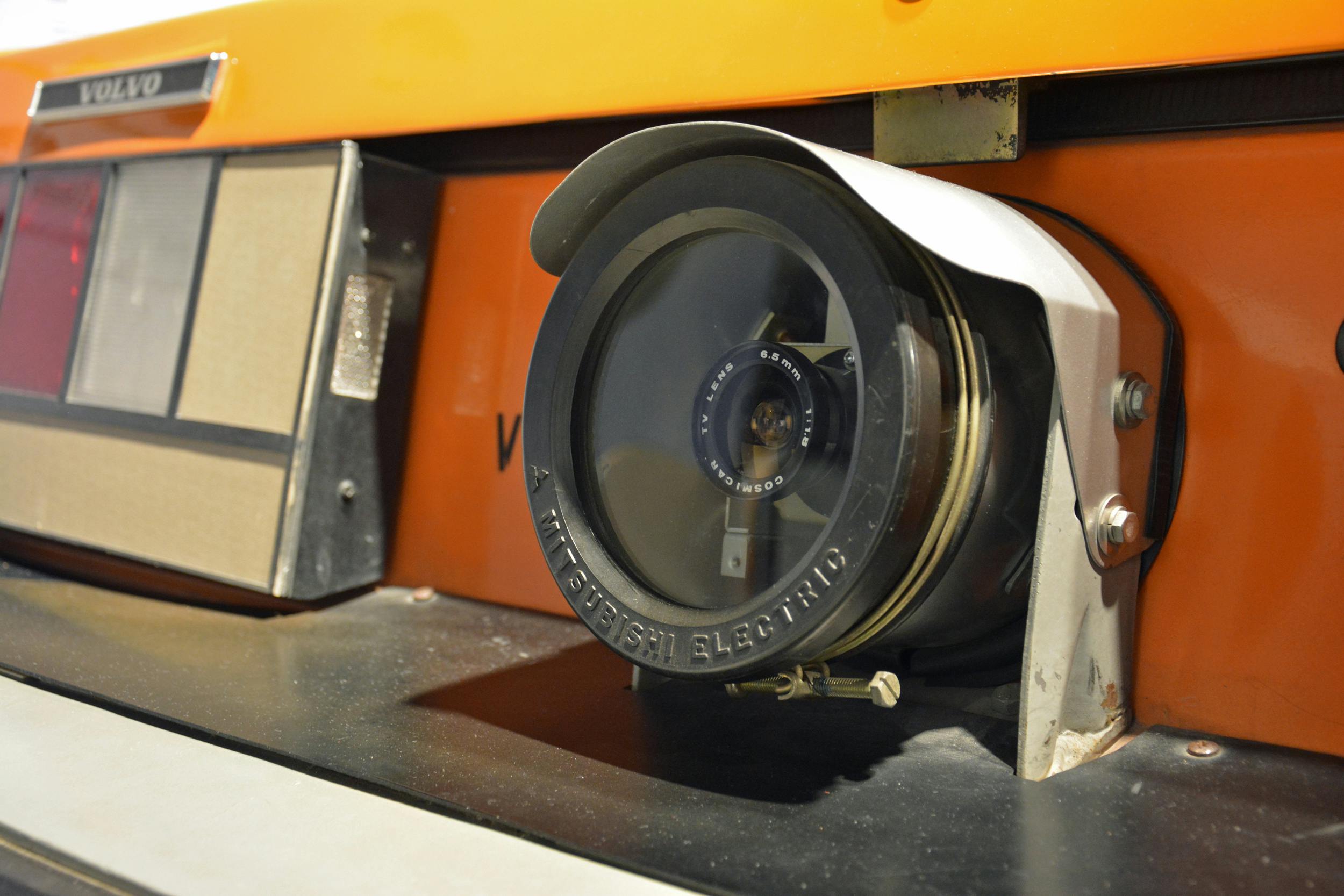

Volvo channeled its decades-long obsession with automotive safety into a prototype named Volvo Experimental Safety Car (VESC), built in 1972. Introduced to puzzled gazes at that year’s Geneva Motor Show, the VESC represented a family-friendly four-door sedan designed with an unwavering focus on safety. The VESC was equipped with automatic seat belts, a rear-view camera that sent its footage to a TV-like screen embedded in the center console, airbags, a collapsible steering column, ABS brakes, and an integrated roll cage. Its park bench-sized bumpers weren’t pretty, but they theoretically allowed the four occupants to survive a head-on collision with another car at 50 mph.

The hood was painted black, race car-style, to reduce glare. It covered a fuel-injected, 2.0-liter four-cylinder engine bolted to a four-speed manual transmission. Engineers even added a catalytic converter, which Swedish law didn’t make mandatory until 1989. These advancements came at a cost: The VESC weighed about 3200 pounds, and bringing it to production would have been extremely expensive. Volvo built and tested just three VESC prototypes.

Though the VESC was never fully realized, some of its safety features, like the oversized bumpers, were engineered into the popular 200 series launched globally in 1974.

1981 Volvo 242C

Bertone helped Volvo turn the 264 sedan into a luxurious coupe named the 262C that would proudly sit atop Volvo’s range. A total of 6622 examples were built from 1977–81, and approximately 75 percent of the production run was exported to the United States. Only about 200 units remained in Sweden.

The coupe displayed in Volvo’s museum is one of four examples custom-built for former company CEO Pehr G. Gyllenhammar. It is painted red, a color not offered to regular customers, and its name is slightly misleading. In Volvo-speak, 262C denotes a 200-series model with two doors, a six-cylinder engine, and a coupe body (as opposed to a two-door sedan). However, the standard PRV V-6 seemingly didn’t sweep Gyllenhammar off his feet, so he requested a 2.2-liter four-cylinder turbocharged to 180 horsepower, 50 more than America-spec cars offered in 1981. This particular Volvo, therefore, should be called the 242C.

1983 Volvo LCP 2000

Though you probably associated the catchphrase “the future of mobility” with autonomous, electric pods, the term is far from new. In the late 1970s, Volvo was already experimenting with ways to build eco-friendly cars that were light and efficient. The Light Component Project (LCP) prototype it unveiled in 1983 showed what a four-seat coupe could look like in the 2000s. Volvo built the LCP using advanced materials such as aluminum, magnesium, plastic, and carbon fiber instead of steel, so it tipped the scale at a mere 1550 pounds.

The LCP was even more fascinating under the hood. Volvo cooked up a turbocharged, 1.4-liter three-cylinder that could run on diesel, palm oil, or canola oil, which might have made its exhaust fumes smell like those of a Belgian fry shack. The 66-hp triple, paired with the featherweight, sleek body, sent the LCP to a top speed of 111 mph.

Volvo made four LCP prototypes (the example displayed in the company’s museum is the last one) to gather data about lightweight materials, but its intention was never to mass-produce the model or anything resembling it. Similar to the VESC, the LCP was exorbitantly expensive to morph into a production car and the business case failed.

1990 Volvo 480 Convertible

The evanescent Sport kept Volvo away from the convertible body style for decades. About an hour north of Volvo’s Gothenburg headquarters, Saab had discovered that American buyers had an insatiable appetite for drop-tops, and it was sending every 900 Convertible it could build across the Atlantic. Robert Koch, design director of Volvo’s Dutch division (which traced its roots to DAF), convinced his Swedish colleagues to give the segment another shot in order to gain a bigger share of the American market.

The Bertone-built 780 would have made an excellent convertible, but Koch started instead with the 480, Volvo’s Renault-powered entry-level model. It was developed and manufactured in Holland, so he was likely more familiar with it than with the big, Swedish-Italian 780. Plus, the 480 was marketed as a zippy performance model designed to lure younger buyers into showrooms, so its personality was well-suited to losing a lid. The transformation was relatively minor; the concept looked like a 480 from the rocker panels to the beltline. Above that, the pocket-sized coupe received a folding top and a tonneau cover, above where the rear seats once were. Koch chose to power it with a 1.7-liter four-cylinder turbocharged to 120 hp.

The members of Volvo’s top brass liked it, but they had one complaint: it wasn’t safe enough. Koch and his team added a roll bar at the last minute to appease them. The end result wasn’t a pie-in-the-sky design study, and it looked ready for production. Sadly, however, it never saw the light at the end of an assembly line. The unfavorable exchange rate between the United States and Sweden led Volvo to cancel its plans to sell the standard 480 on American shores, so bringing a hypothetical convertible version became prohibitively expensive. It didn’t help that some of the suppliers who contributed to the project filed for the bankruptcy shortly after the drop-top made its debut. Motorists seeking a top-less Swedish car had to visit a Saab dealership until Volvo unveiled the 850-derived C70 at the 1996 Paris Motor Show.

Have an eccentric Swede of your own? Drop us your story in the comments below.