Media | Articles

Spin Doctor: 100 years ago, one man proved turbocharging’s worth

Following the invention of the gasoline and diesel internal-combustion engines at the end of the 19th century, engineers concentrated on raising power output. In 1885, Gottlieb Daimler of Germany experimented with a crankshaft-driven supercharger. In 1905, Alfred Buchi of Switzerland, and in 1916, Auguste Rateau in France, independently patented devices then known as turbo-superchargers. What we now call turbocharging utilizes the same principle: recycle waste exhaust energy to spin a compressor boosting intake pressure, and power output rises accordingly.

Were it not for World War I, this technology might have languished in labs for decades. Enter General Electric engineer Dr. Sanford Moss. In 1918, he was tapped to employ turbocharging to diminish horsepower losses resulting from flying through thin air at altitude.

Moss, born in 1872, studied steam turbines in his University of California mechanical engineering classes. His master’s thesis proposed replacing locomotive piston engines with smoother gas turbines. His doctoral thesis at Cornell, dubbed “The Gas Turbine, An Internal Combustion Prime Mover,” piqued the interest of General Electric executives interested in powering their electric generators with turbines. In 1903, Dr. Moss was hired by GE to serve as the company’s resident turbine expert.

During World War I, German aircraft engine builders BMW, Maybach, and Mercedes built fighter-plane engines featuring monstrous piston displacements and high compression ratios, to offset the losses from breathing thinner air at altitude. Those engines employed three throttle levers opened progressively to keep the engine from imploding at sea level, and they successfully climbed to 20,000 feet.

In France, engineer Rateau turbocharged a Renault aircraft engine toward the same end. His work increase climb rate and top speed by 15 percent. To keep America competitive in the global fight, turbocharger experimentation began in the same period at the U.S. Army Air Service’s McCook Field, in Dayton, Ohio. William Durand, chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (a NASA progenitor), who was familiar with Moss’s turbine expertise, petitioned GE to reassign him to Ohio.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

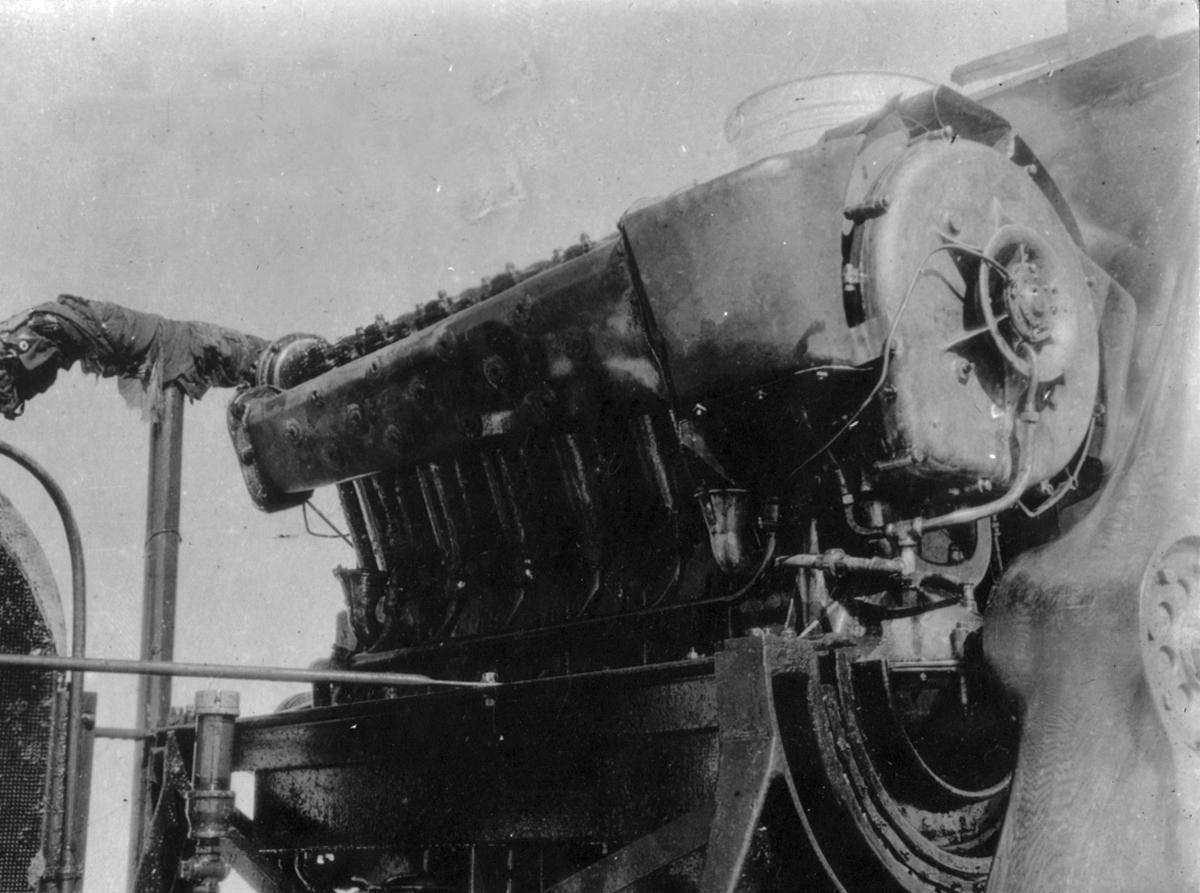

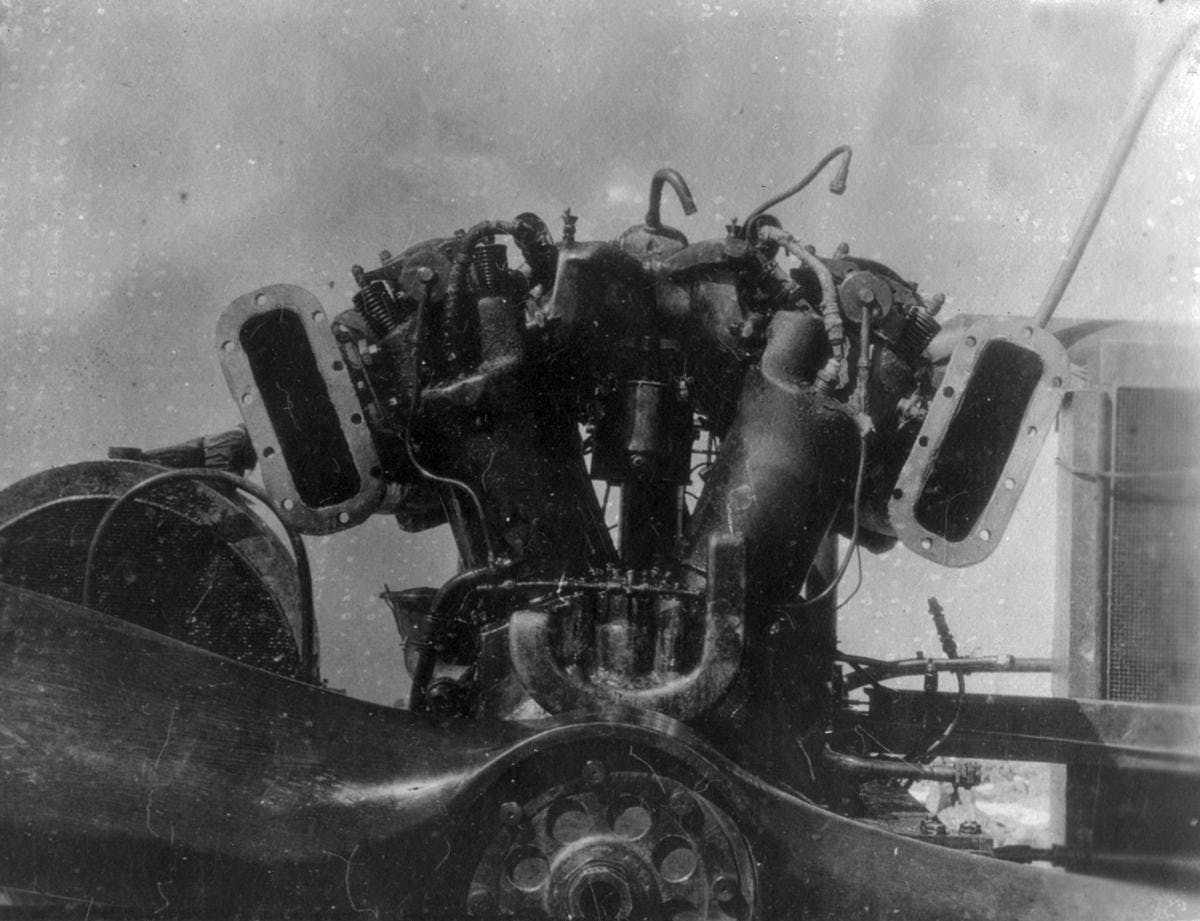

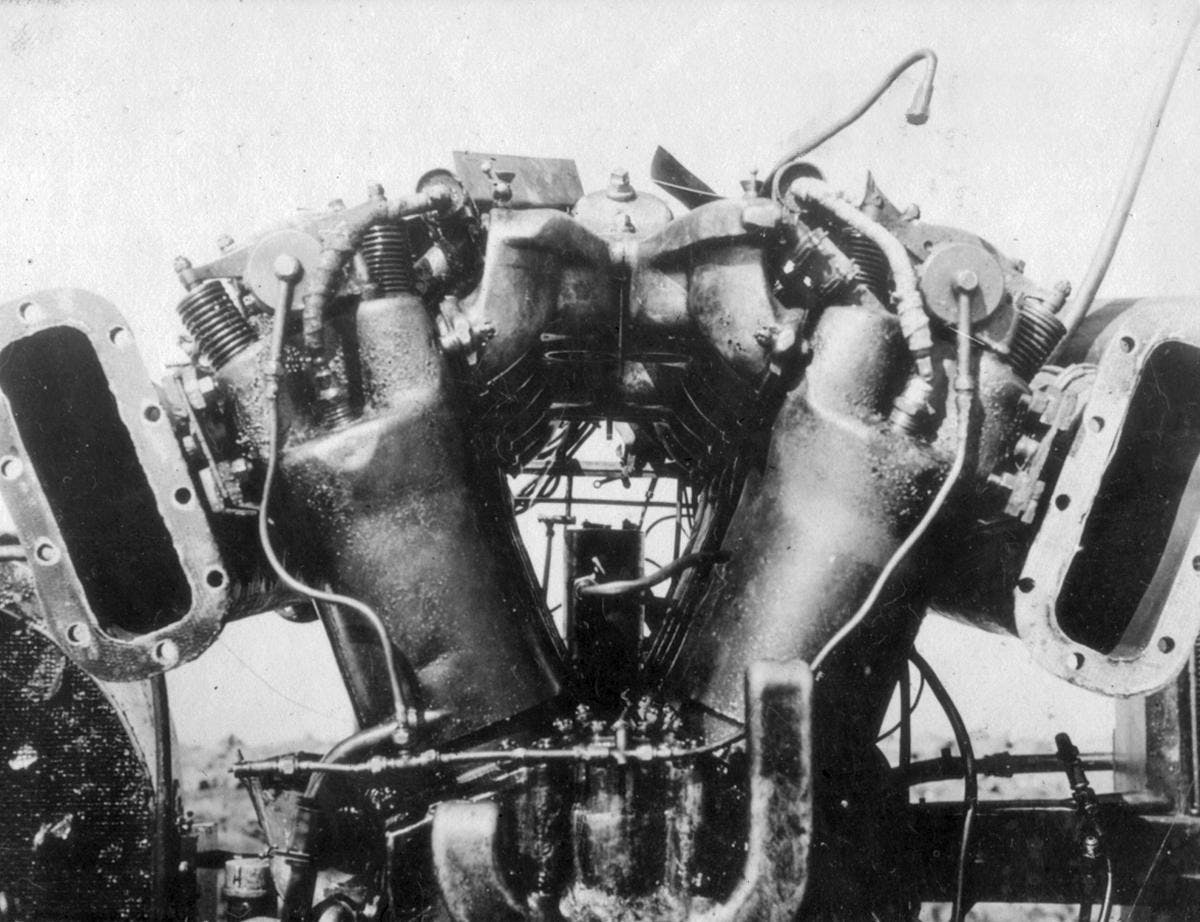

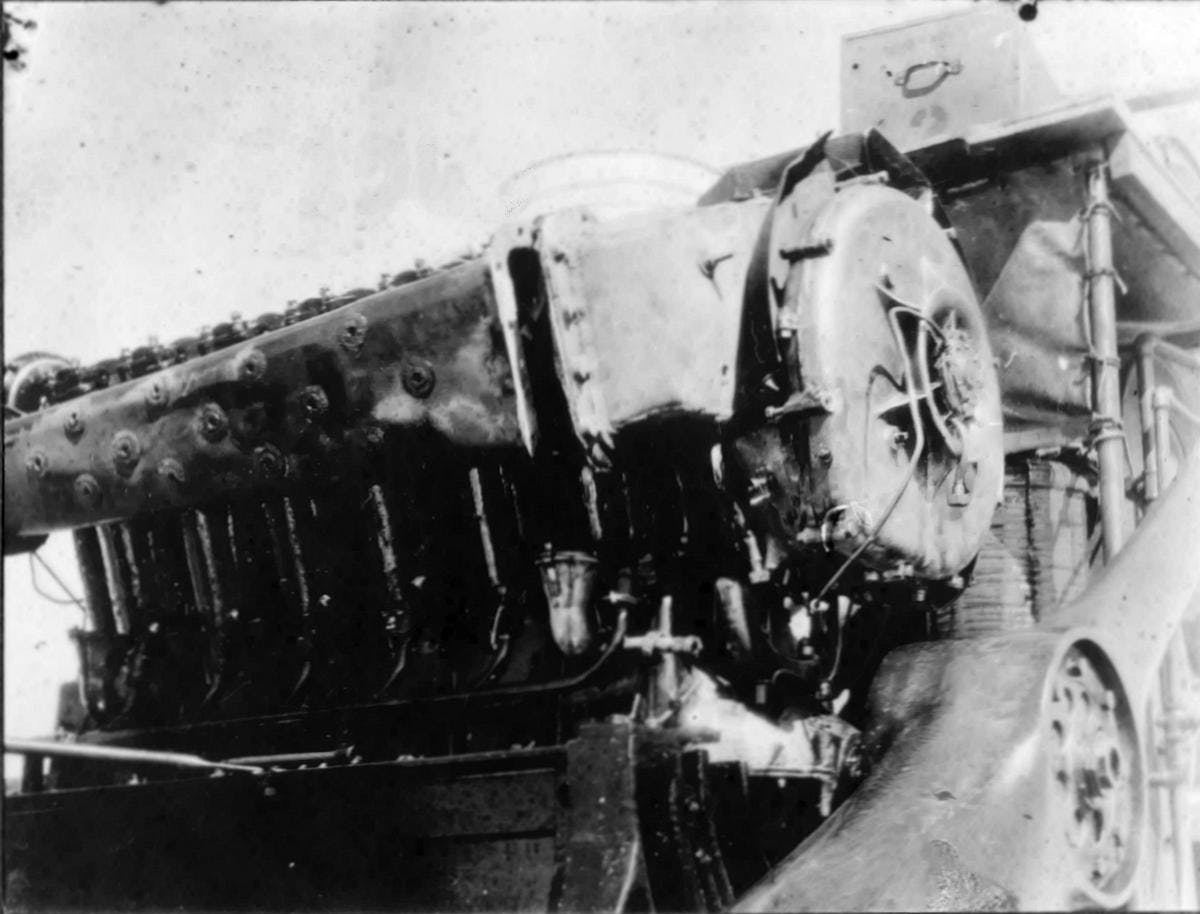

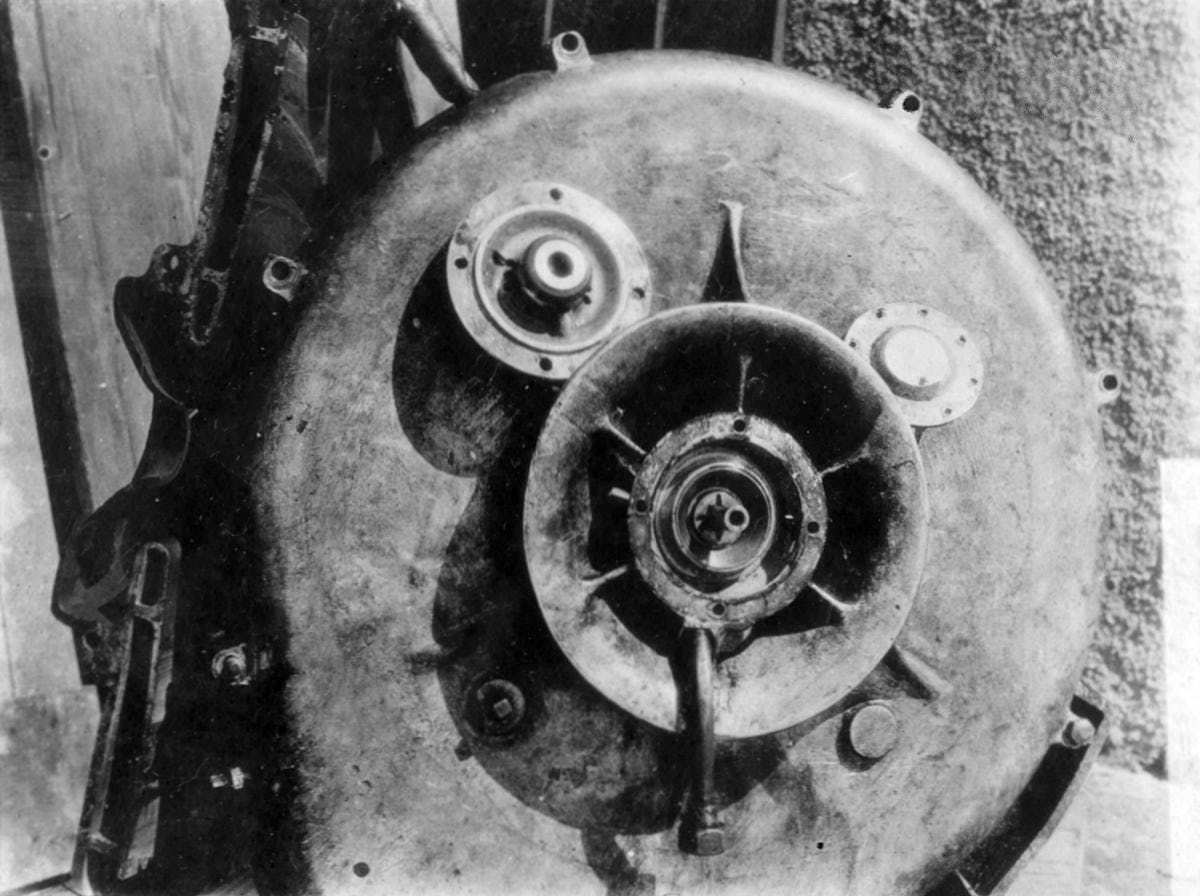

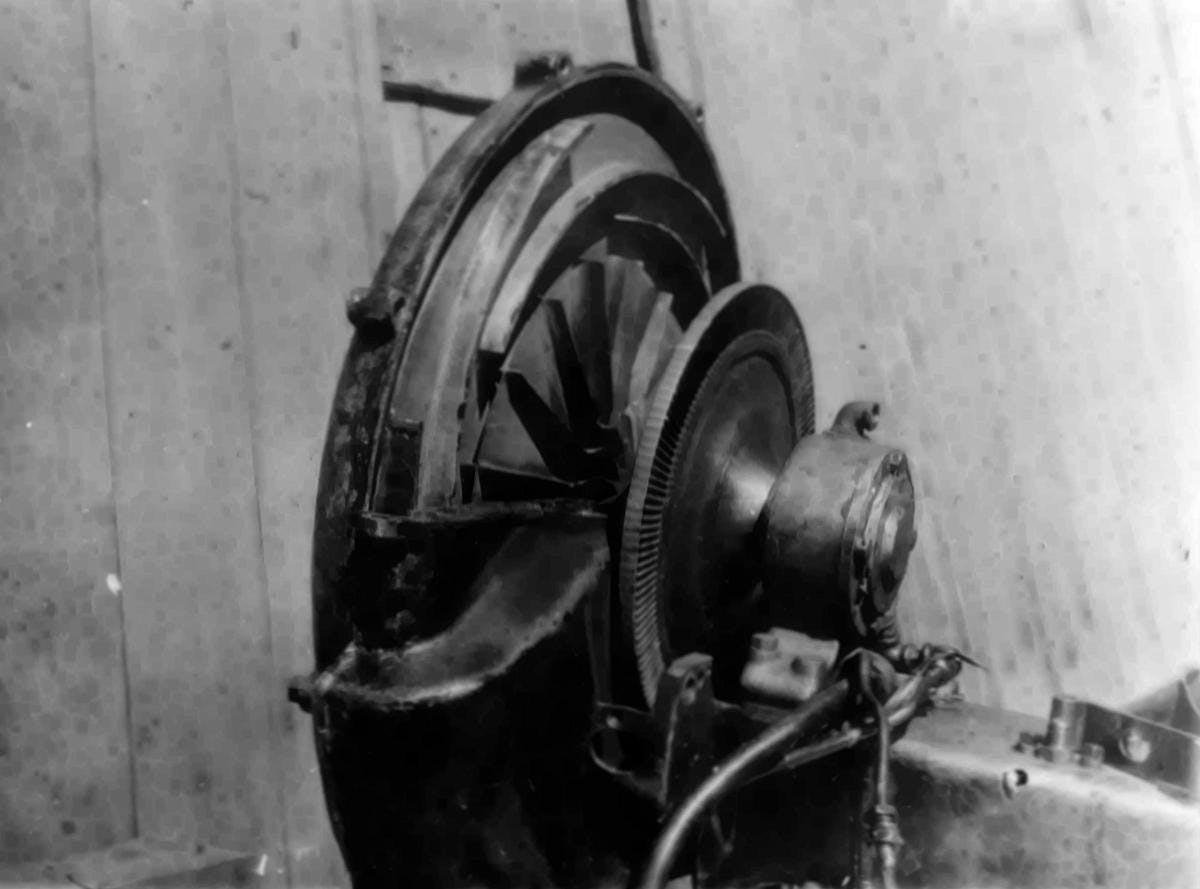

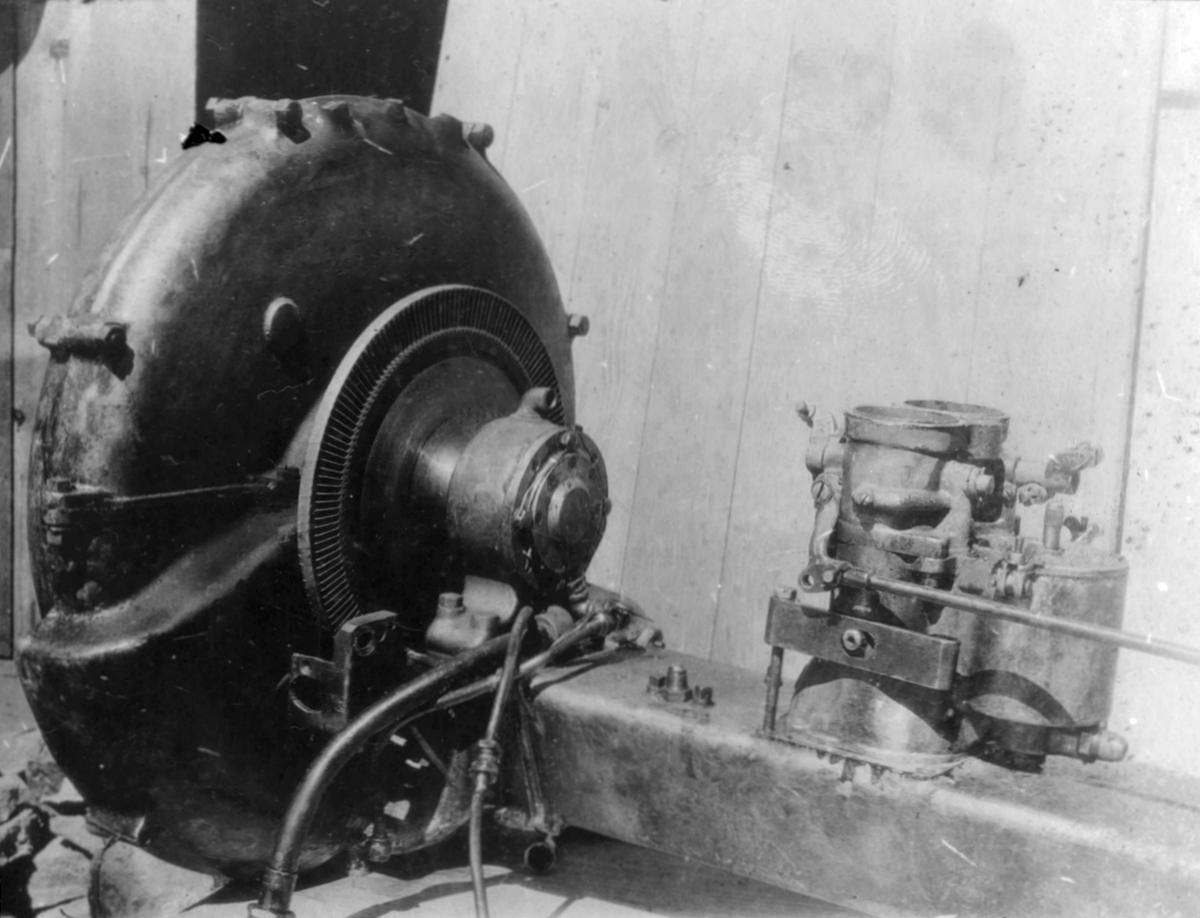

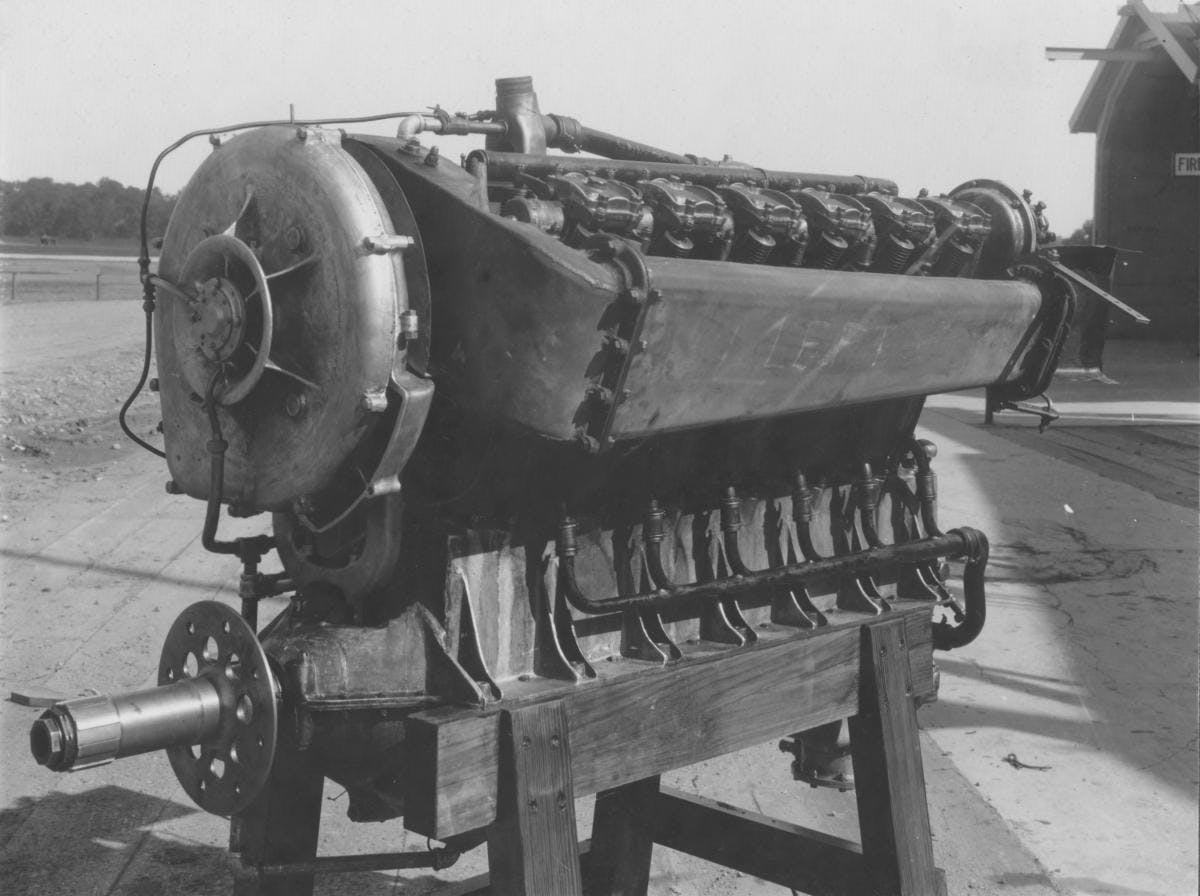

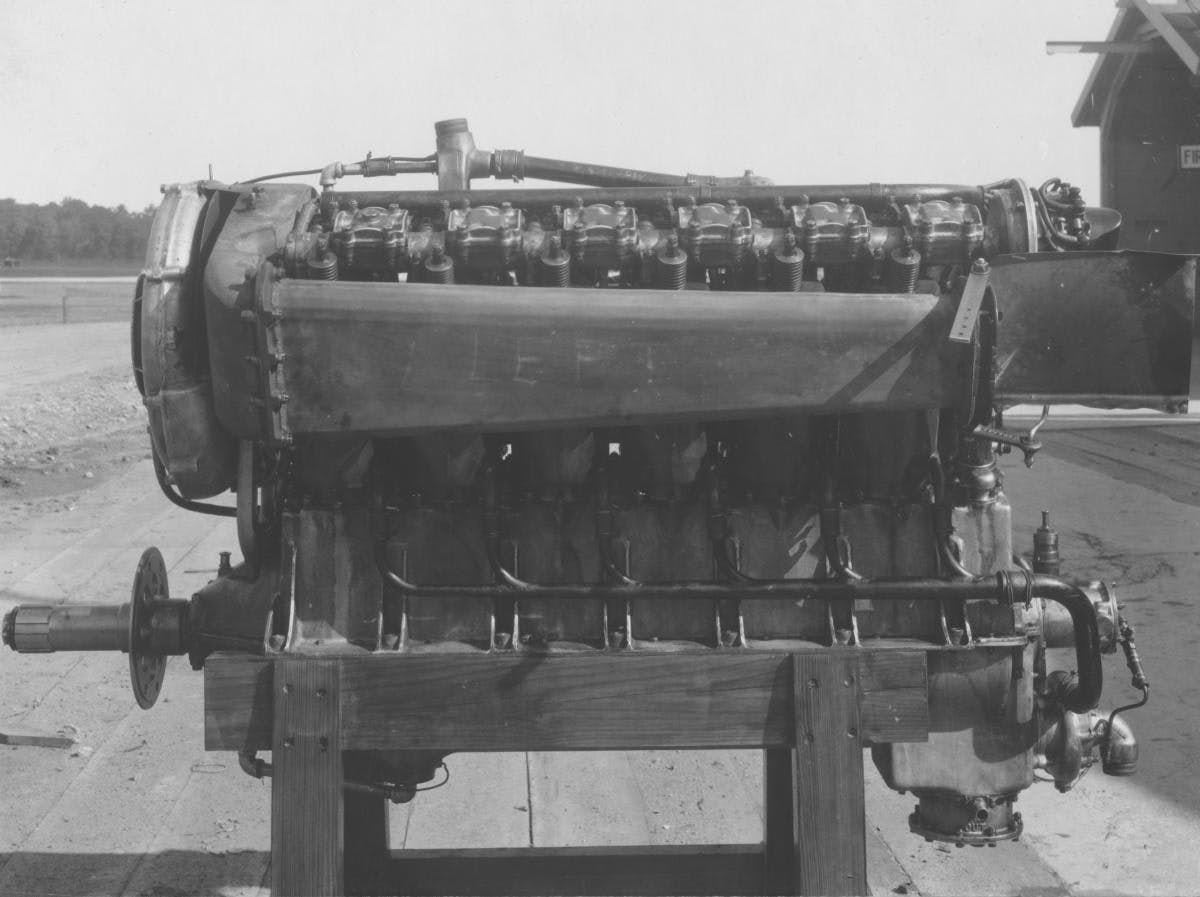

Moss’s initial studies employed 10-inch turbine and compressor wheels spinning at 20,000 rpm. On a 27-liter Liberty V-12 aircraft engine producing 400 naturally aspirated horsepower at 1700 rpm, those components raised output to 470 horses at the same speed. The V-12’s exhaust manifolds wore wastegates for the expulsion of excess boost pressure. The added stress caused spark-plug failures and other issues, but the government nonetheless issued GE its first production turbocharger contracts in 1918.

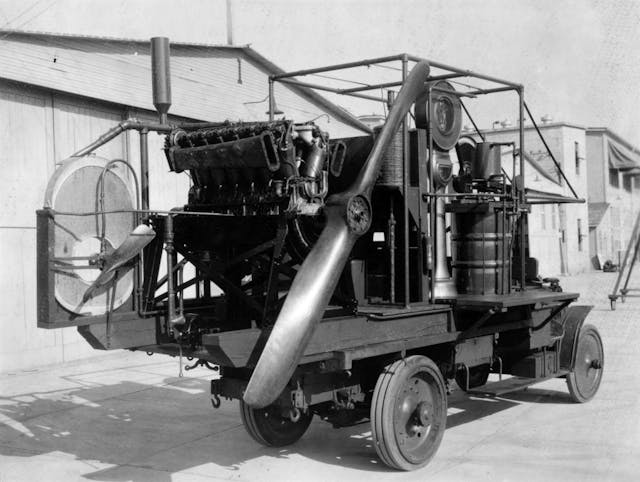

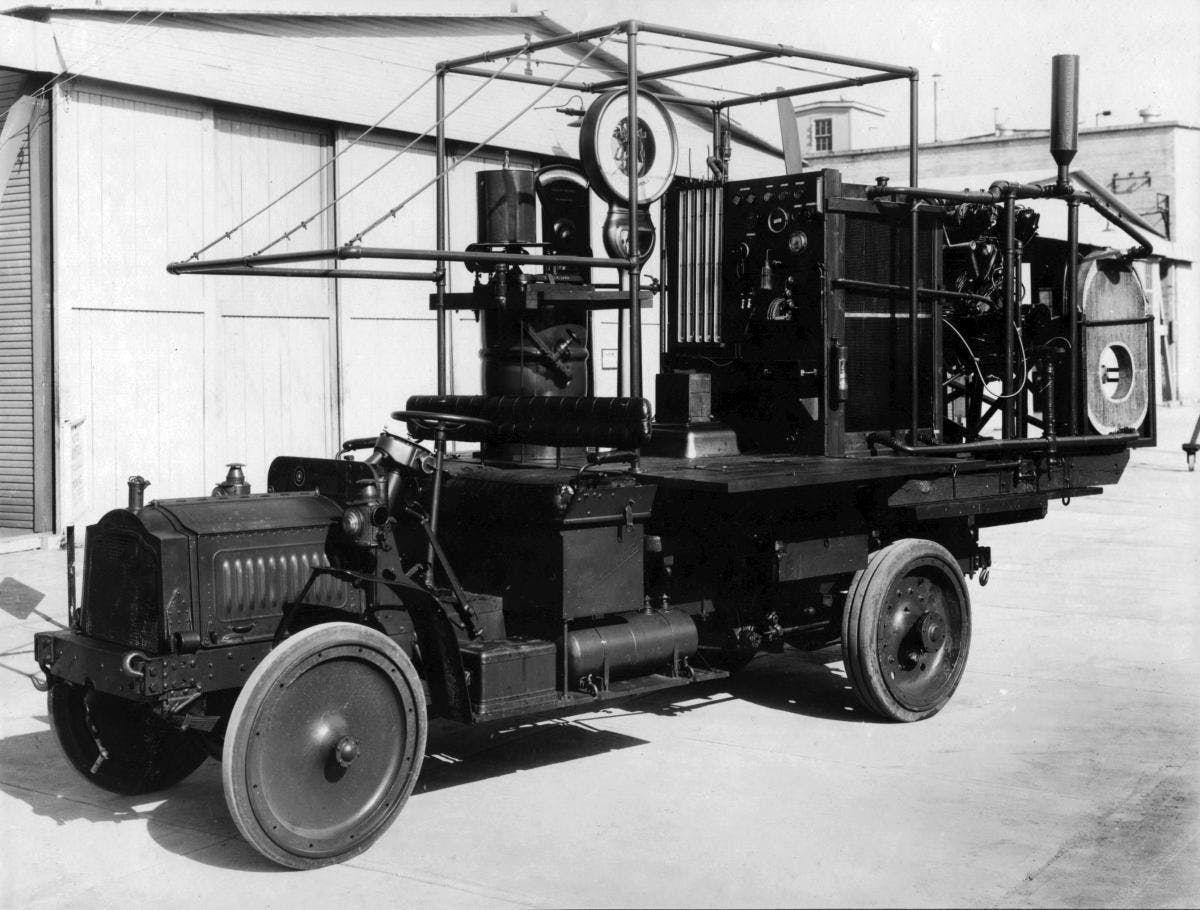

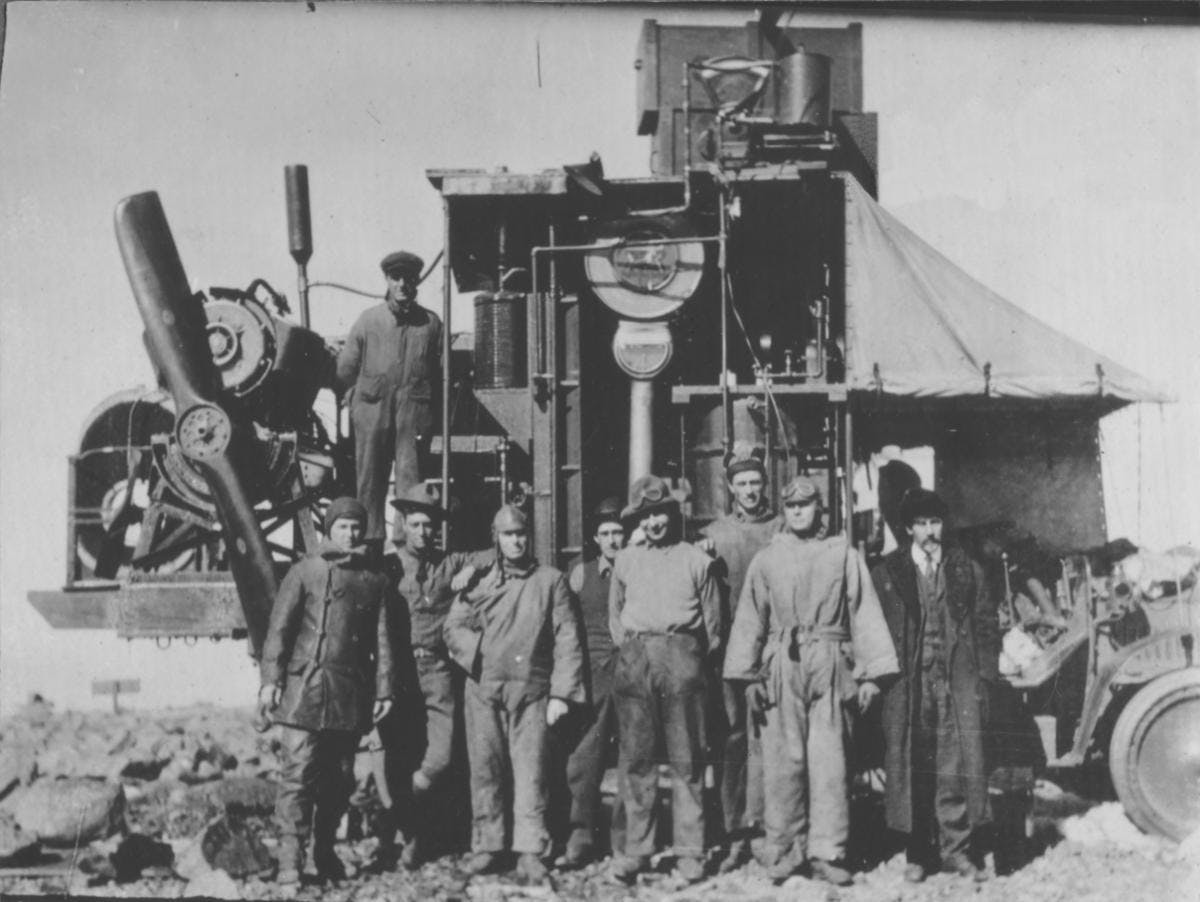

That’s when Moss’s brainstorm kicked in. To avoid subjecting a pilot and aircraft to risky in-flight experimentation, his inspired alternative was a mobile laboratory: He mounted the turbocharged V-12 and its dynamometer on the bed of a Packard truck, then shipped the whole assembly 1300 miles by train to Colorado Springs, for high-altitude testing.

When the rig arrived, Moss and his technicians proceeded to drive it up the unpaved Pikes Peak Auto Highway, some 23 miles, to the 300-foot pad at mountain’s 14,115-ft summit. Work began there on September 10, 1918.

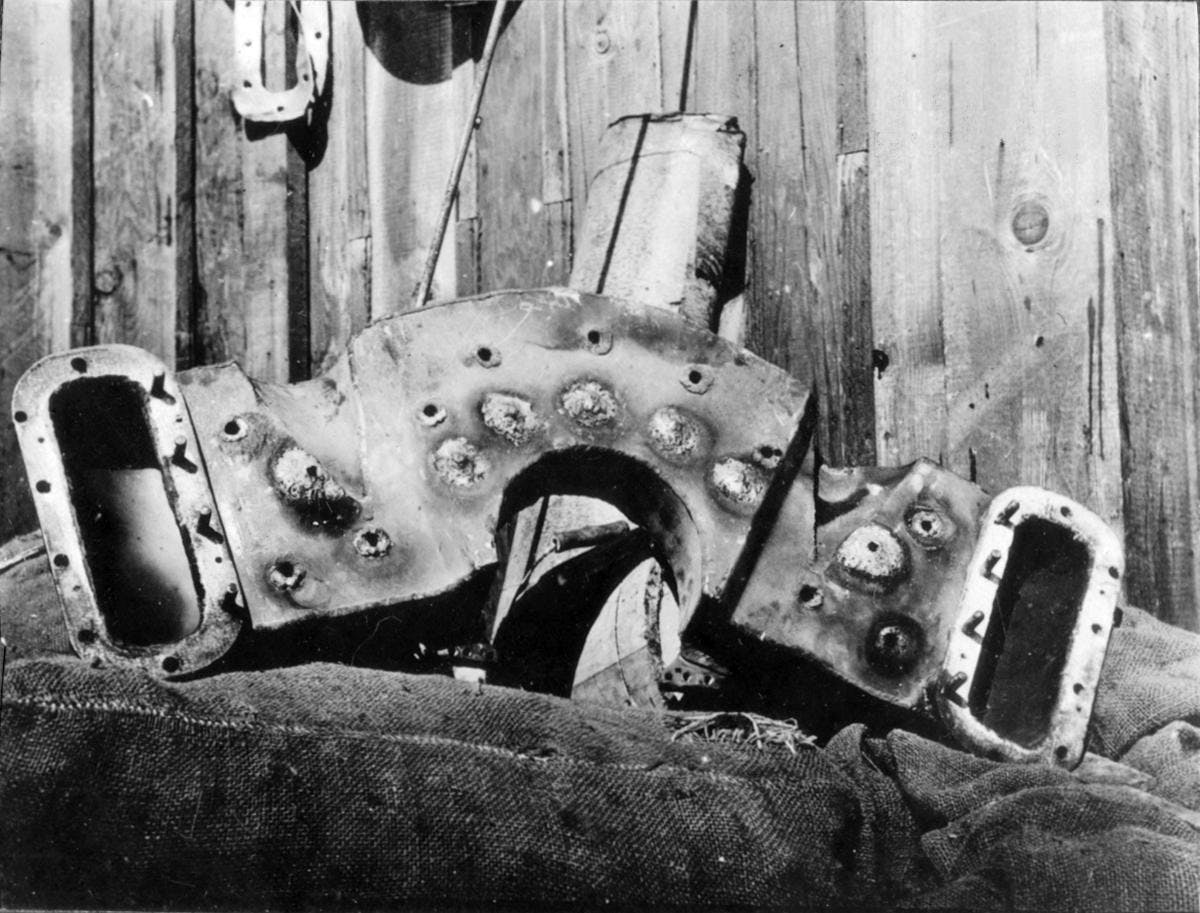

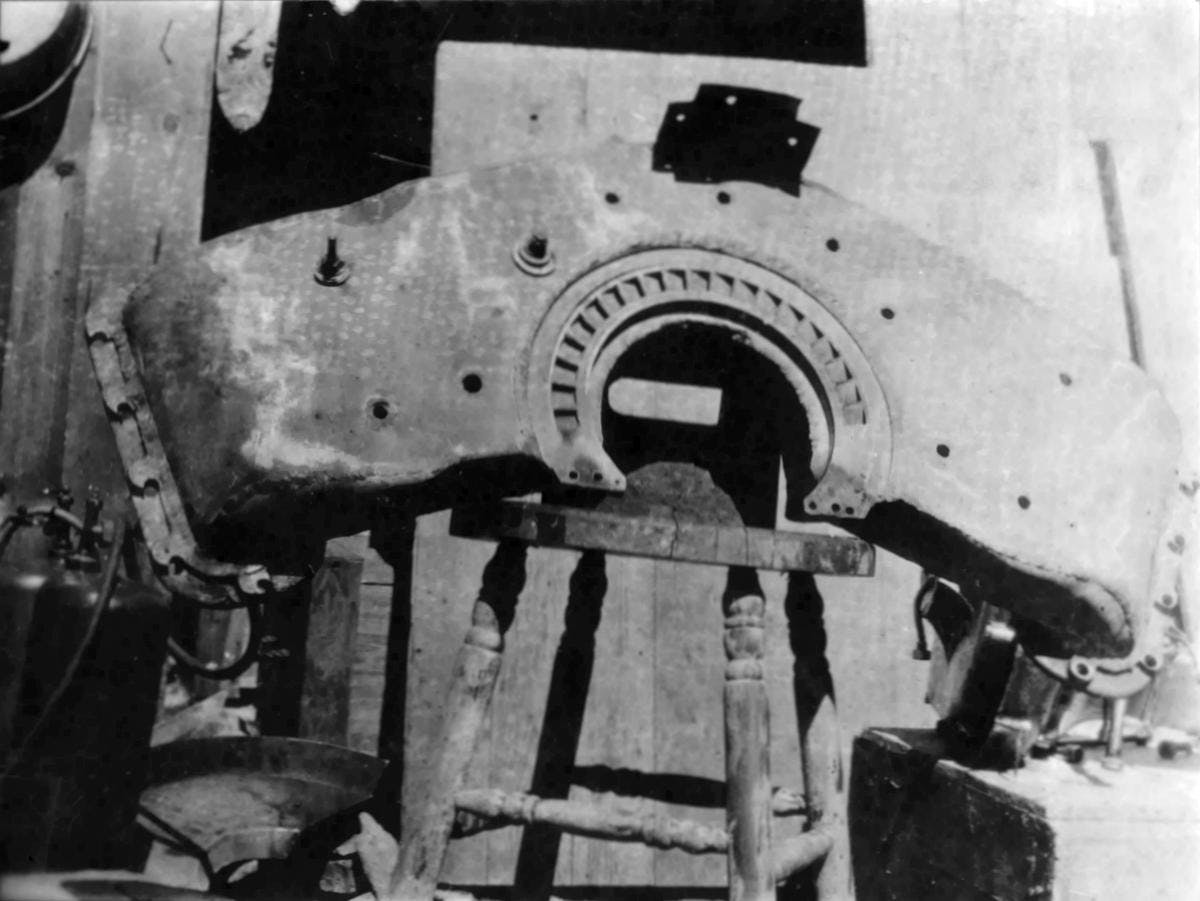

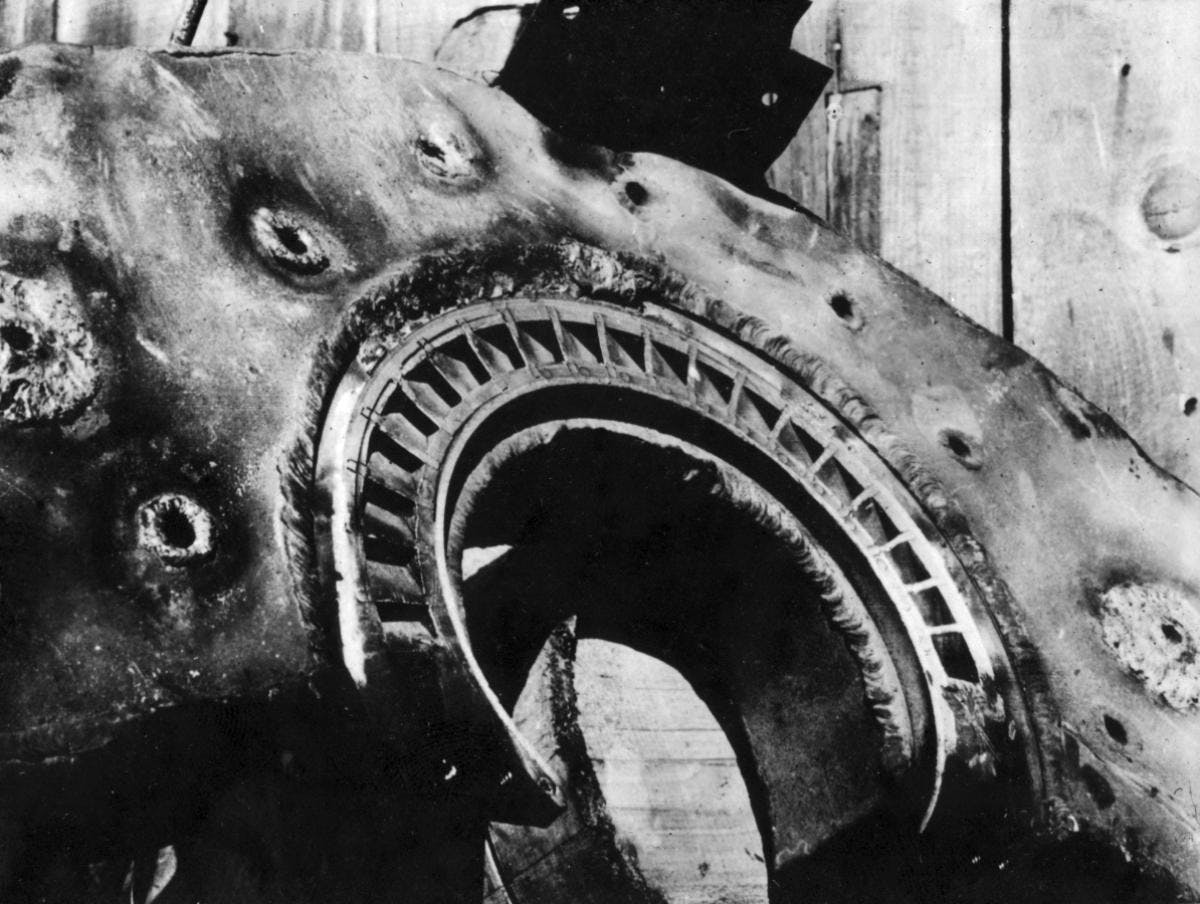

In the month that followed, Moss orchestrated around 25 test runs. Each evening, the test rig was covered in canvas before the team drove down the mountain to rest. On a few occasions, Moss’s equipment grew frozen inside a cocoon of snow. A small shack on the mountaintop served as repair shop. Major repairs would have necessitated lugging the whole test assembly back down the mountain; fortunately, that was never necessary. The most notable issues were clogged carburetor jets, leaks in the exhaust manifold and compressor housing, failed turbo thrust washers, and a few broken exhaust-manifold bolts. “There were many pleasant days when work could be carried on with facility,” Moss later noted, stoically.

Moss’s experiments decisively proved the merits of turbocharging. Baseline sea-level tests conducted at McCook had the Liberty producing a maximum of 354 hp at 1800 rpm. Atop Pikes Peak and without the turbo, output plummeted to 230 hp. Equipped with boost there, the V-12 peaked at 377 hp, though that maximum could be sustained for only 30 seconds before spark-plug failure set in. (The turbo Liberty did successfully survive a four-hour endurance test while producing 313 hp.) All of these measurements were taken while the engine was driving a spinning propellor, with the attendant drag load, in contrast to the 400–470 hp unburdened output quoted earlier.

After ongoing development, Moss installed a turbo Liberty in a LePere biplane, aiming to challenge the international altitude record. That aircraft topped 40,000 feet in 1921, double what a naturally aspirated LePere could achieve.

Moss retired in 1938, two years before he was awarded the Collier Trophy for his achievements. During World War II, he consulted with GE and the Army Air Force, developing experimental turbine engines for the Bell XP-59A, America’s first jet.

Turbos arrived too late for use in World War I, but they soon became decisive military assets. GE and Ford manufactured more than 300,000 during World War II.

Moss died in 1946 at 74, in Lynn, Massachusetts. In 1953, on the fiftieth anniversary of powered flight, Air Force lieutenant General James Doolittle placed a monument at the top of Pikes Peak to commemorate Moss’s achievements. They were deemed instrumental to high-altitude aviation.

Inevitably, turbos descended from the sky and benefitted ground transportation. The most significant firsts are:

1950: Cummins introduces turbodiesel truck engines.

1952: After qualifying on the pole in a turbocharged car, Fred Agabashian leads the Indy 500 for 70 laps.

1962: Oldsmobile introduces the seminal turbocharged Cutlass F-85 Jetfire. The car is quickly followed by Chevy’s turbocharged Corvair Monza Spyder.

1966: The Indy 500 sees its first turbocharged Offenhauser engines. The venerable four-cylinder, long the dominant engine at the Speedway, would earn its first win with forced induction in 1968.

1968: BMW wins the European Touring Car Championship with a turbocharged version of its 2002 sport sedan. A production variant followed in 1974.

1969: Turbochargers arrive in the Canadian-American Challenge road-racing series—a.k.a. the Can-Am—eventually providing for outputs in excess of 1000 hp.

1972: Porsche and Penske team up to race turbocharged, twelve-cylinder 917s in the Can Am. The cars are so successful that they essentially kill the series.

1974: Porsche launches its road-going 911 Turbo.

1976: Turbo engines dominate the Le Mans 24 Hour race.

1977: Renault introduces its landmark RS10 Formula 1 car, one of the earliest turbocharged open-wheelers. Turbos will dominate the sport in a matter of years.

1982: Honda launches its CX500T, the first turbo production motorcycle.

1983: Nelson Piquet wins the Formula One Championship with a turbocharged, four-cylinder Brabham-BMW. Qualifying outputs reportedly crested 1000 hp. Exact measurements aren’t known, as BMW’s dynamometers could read no higher.

1987: Limited-edition turbocharged Buick Regal GNXs wear bumper stickers bragging, ‘We brake for Corvettes.’

1989: Chrysler launches a turbocharged minivan.

2002: Honda introduces a turbocharged personal watercraft.

2006: Some 41 new vehicles in the American market are turbocharged. Just 17 wear superchargers.

2008: Every U.S. car and truck powered by a diesel engine comes equipped with at least one turbocharger.

Today we take this horsepower helper for granted. Seventy-five years after his passing, Dr. Sanford Moss deserves appreciation for turbocharging our power and performance.