Media | Articles

The only thing weirder than my obscure cars? My obscure car books

I often get accused (rightfully) of being a fanatic of communist cars. That’s obviously true … but not exclusively so! I’m a crazed fan of any automobile with a good story, and the more obscure, the better. This attitude attracts far too many immobile objects with non-existent spare parts into my possession, and I struggle to keep a single-digit inventory. The whole collecting thing, luckily, started small. Ask my parents about the 55-gallon drum full of garage-sale Hot Wheels, Matchbox, and Majorette cars in their attic. Actually, don’t; you’ll be roped into trying to convince me to reclaim them.

Matthew Anderson is an American engineer who relocated to Germany a few years ago for work. In his spare time, with reckless abandon, he pursues a baffling obsession with unexceptional Eastern Bloc cars. We don’t ask him too many follow-up questions.

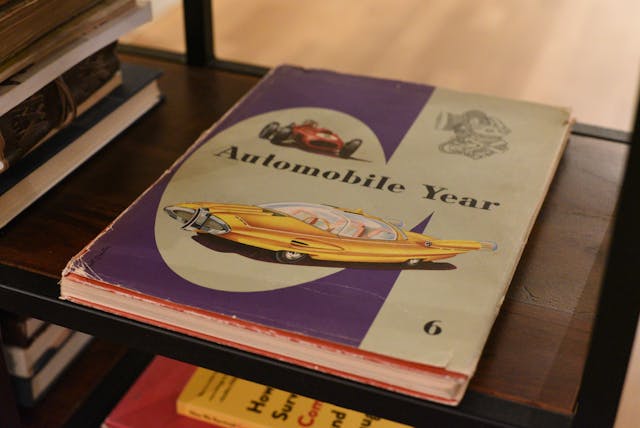

In parallel, books started to wend their way into the picture. First was a Japanese catalog of every single car built globally in 1991, which my father brought back from a business trip to Tokyo. After that, in first grade, came a Lamborghini book, followed by a photographic history of Ford from 1946–1990. Interest turned into obsession by way of my first real paid job, in eighth grade: organizing a shed full of 1960–1970s car magazines for $5 an hour. In comparison to toy cars, the information density per square inch proved vastly higher. Overall content of obscurity on the bookshelf can far exceed what can be parked in one’s garage, or in my current case, driveway, friend’s garage, warehouse, or farm. I’d like to provide for you, dear reader, a brief window in to my car book collection. It should surprise nobody that the contents are mostly communist or Australian in origin, and nearly always valued at under $5.

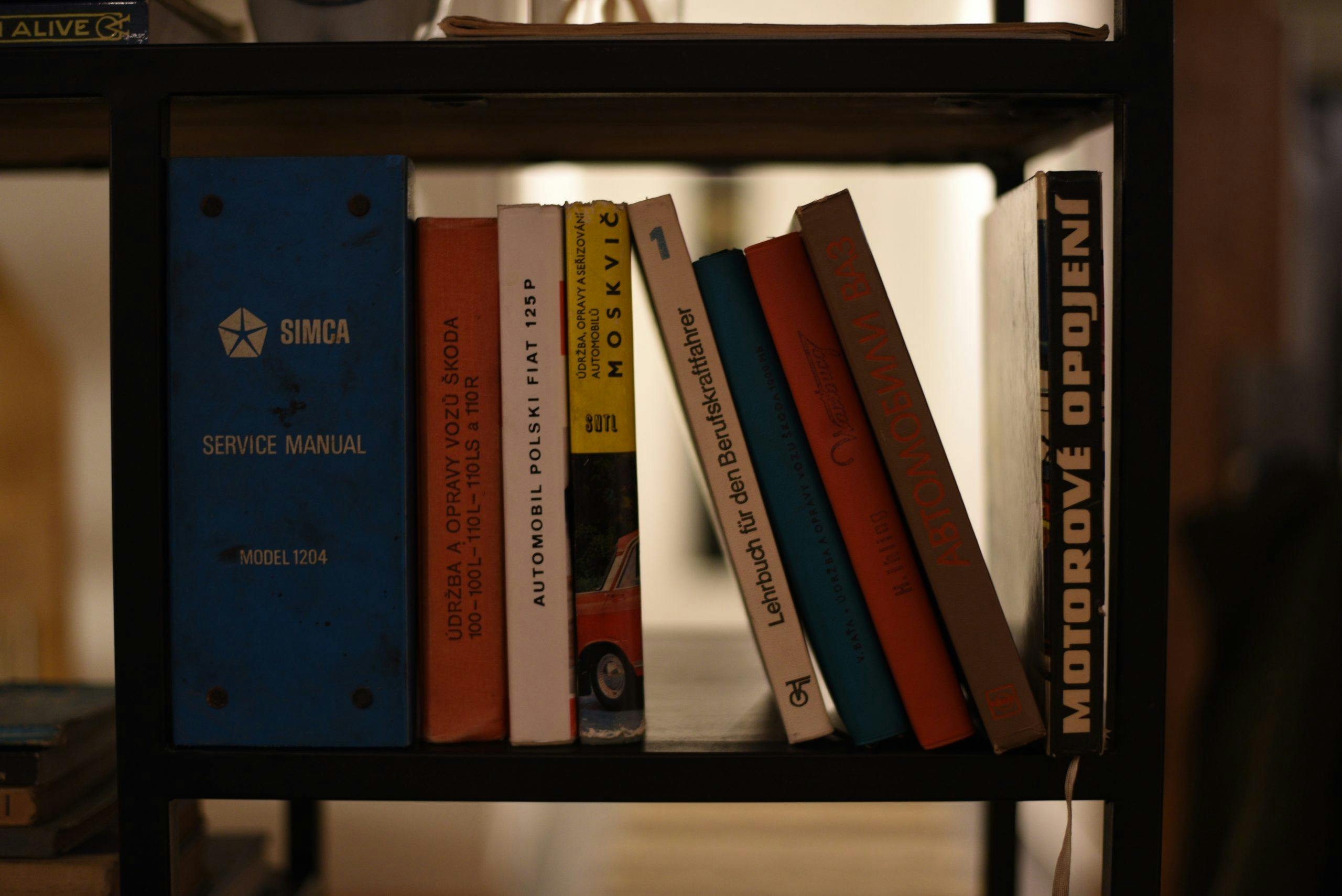

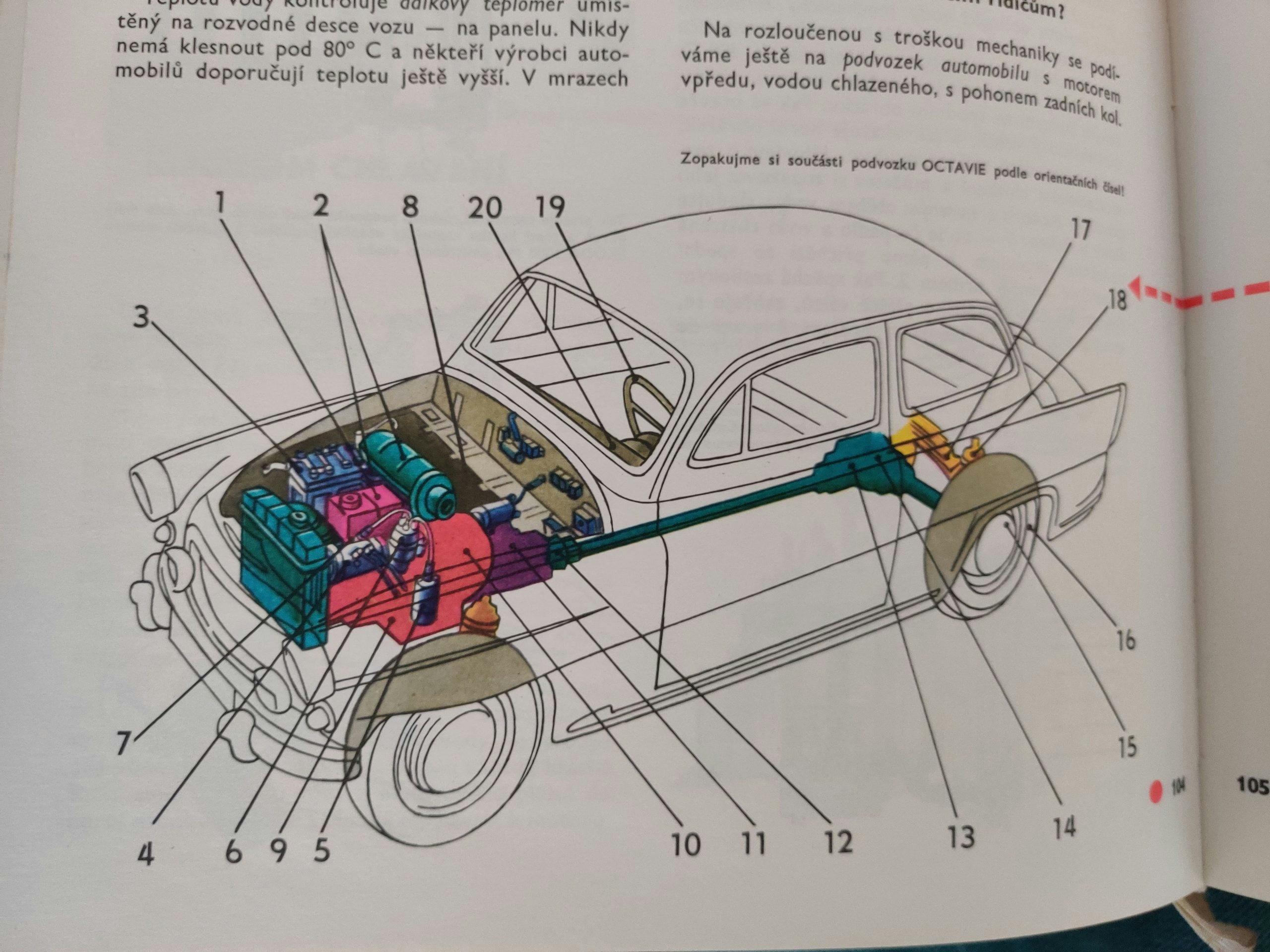

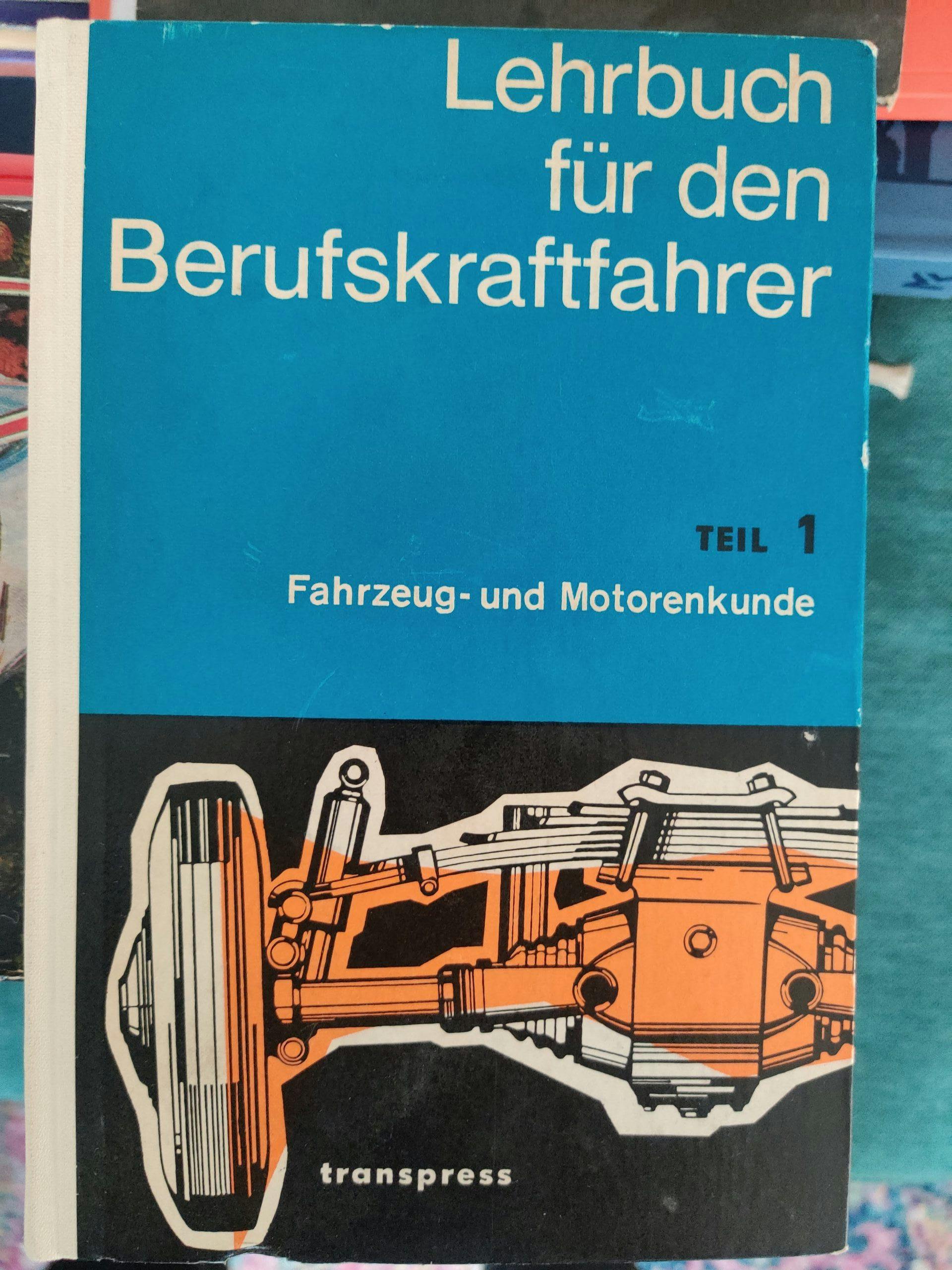

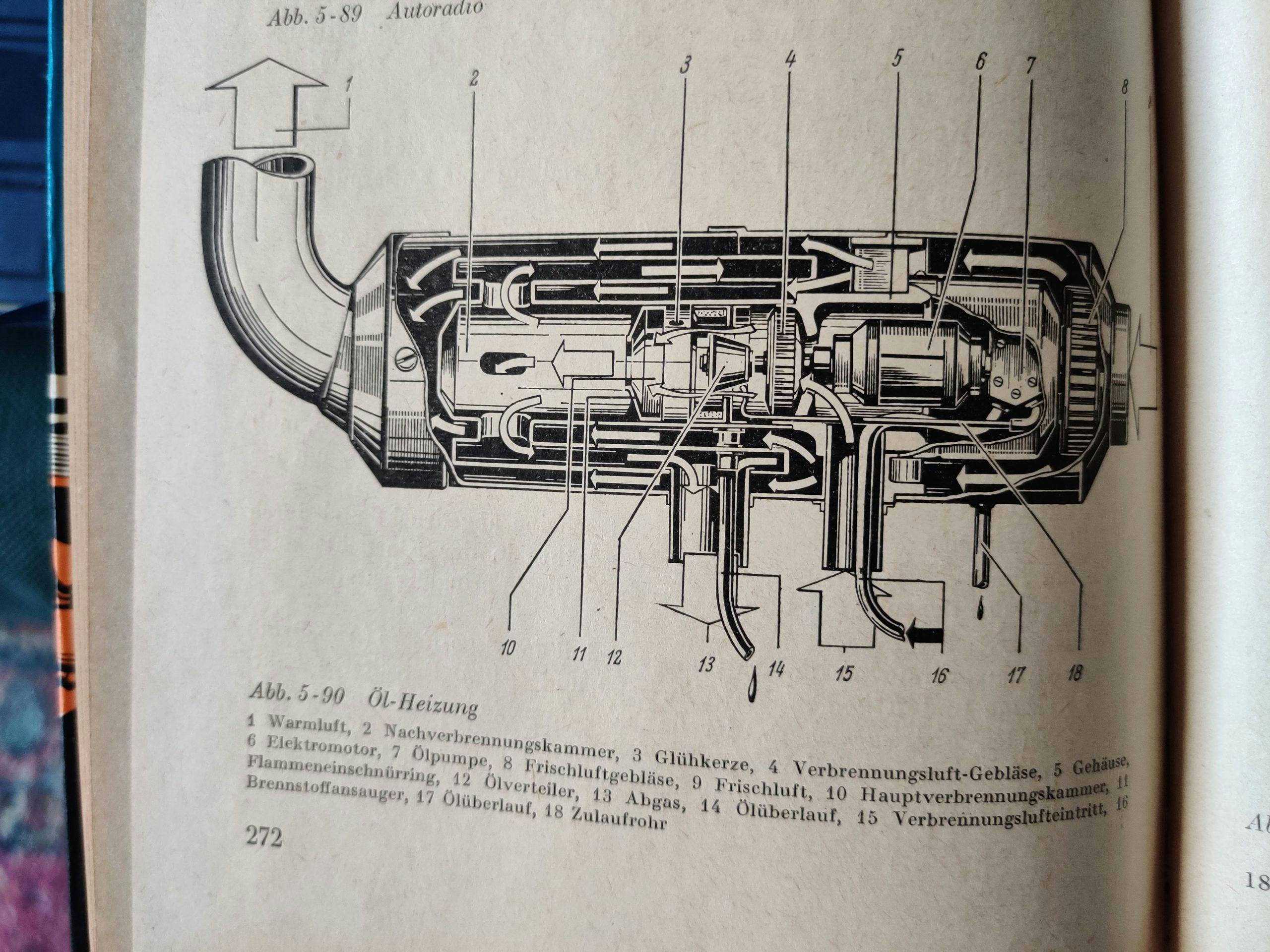

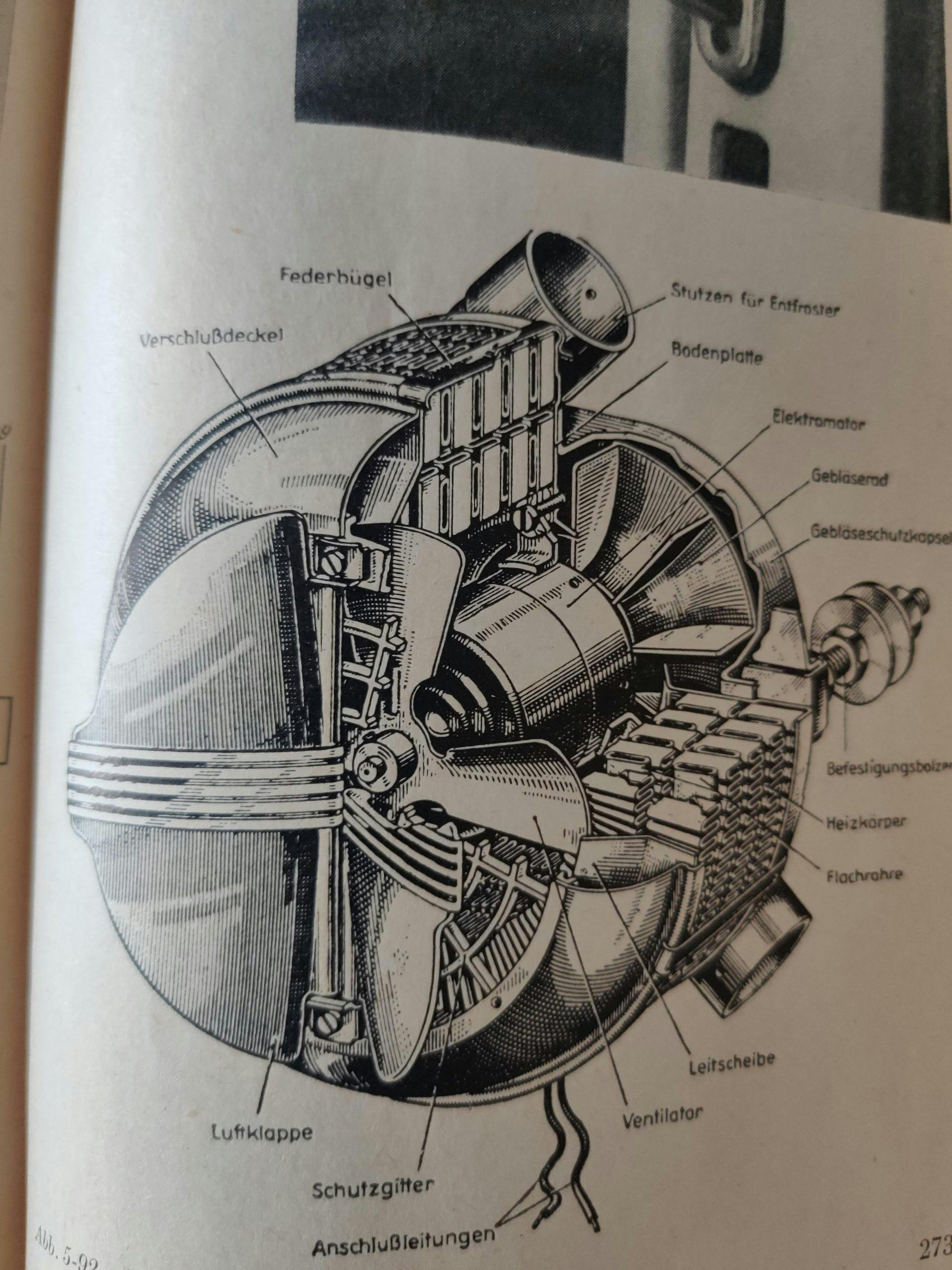

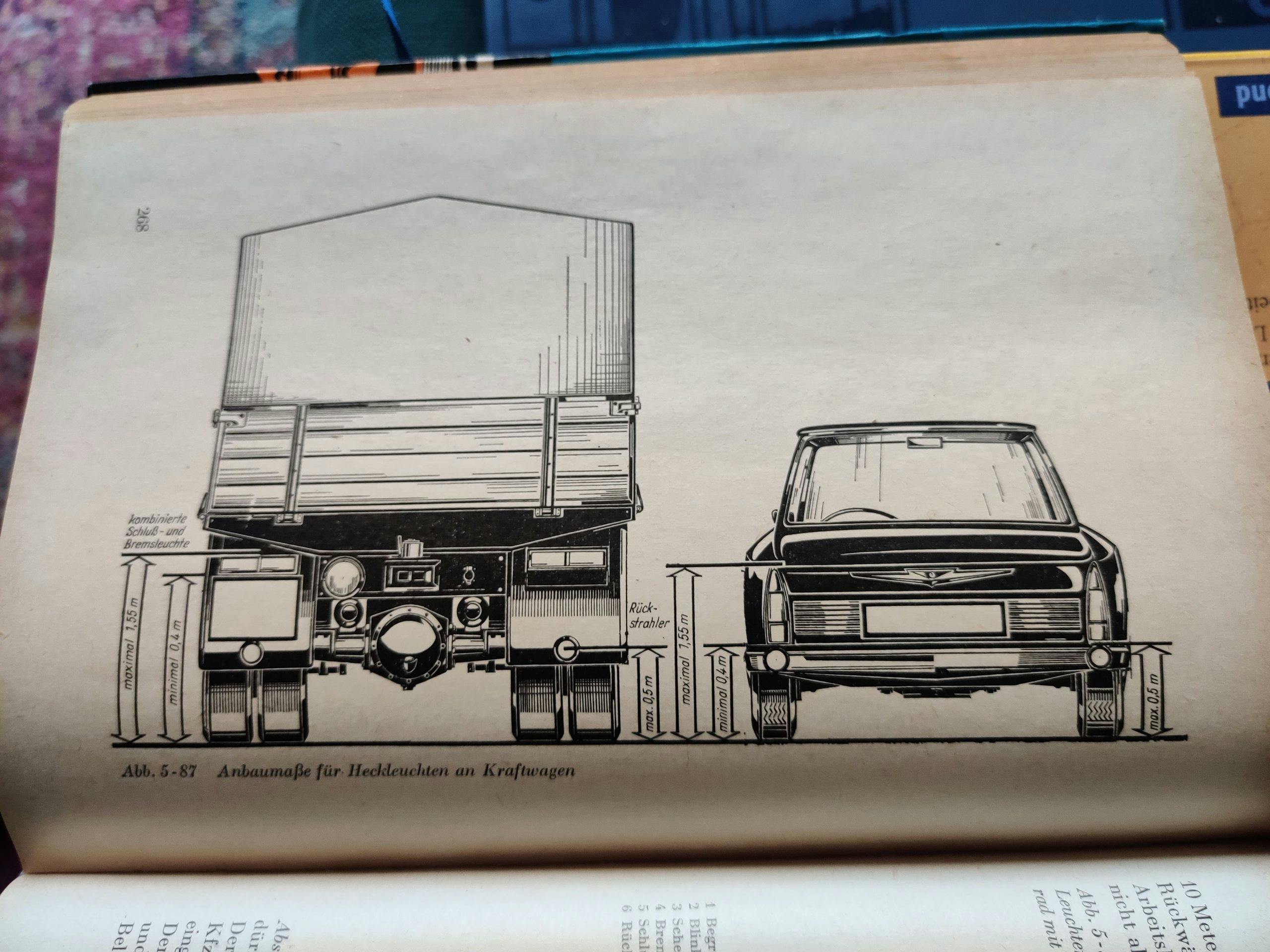

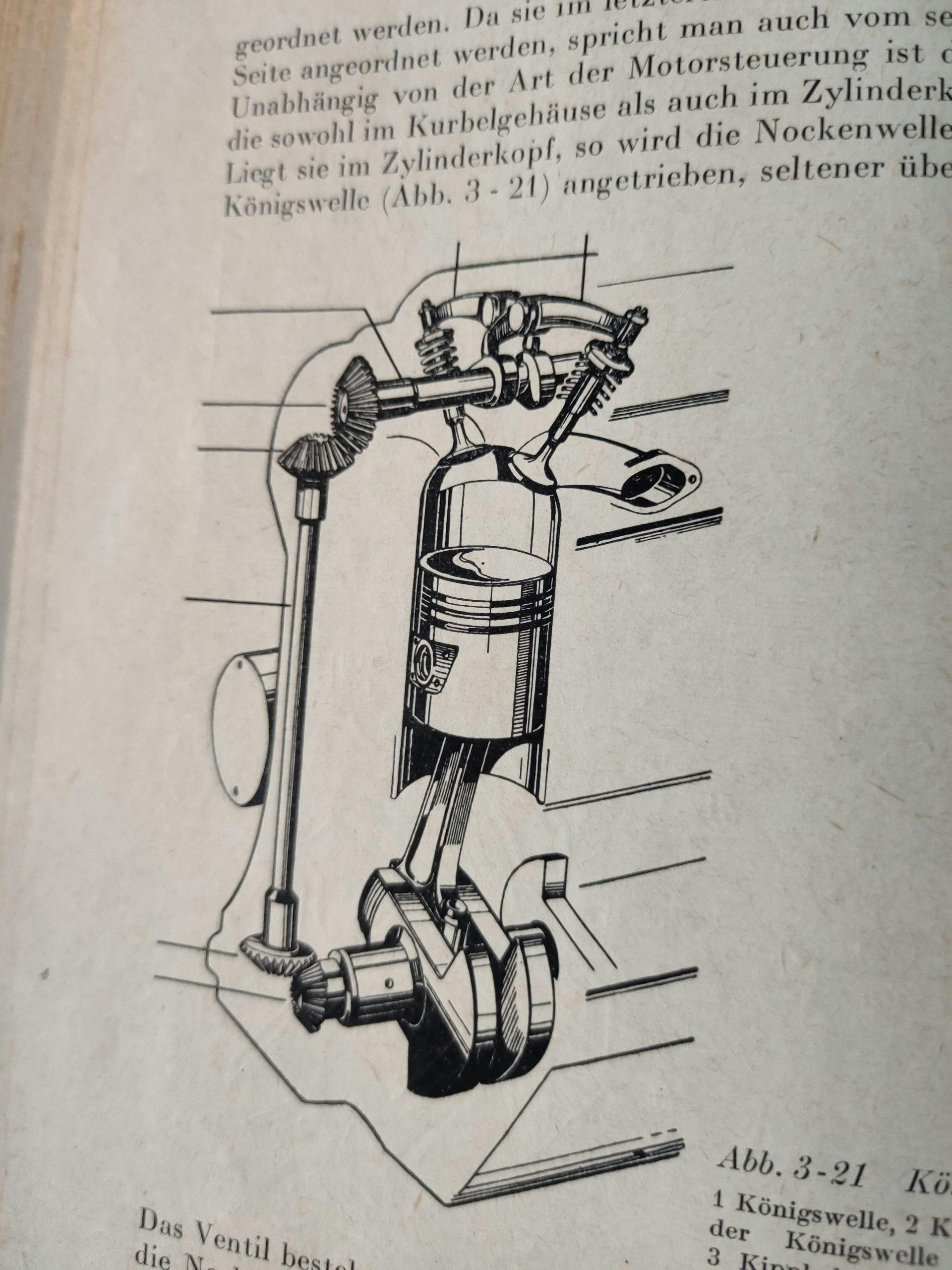

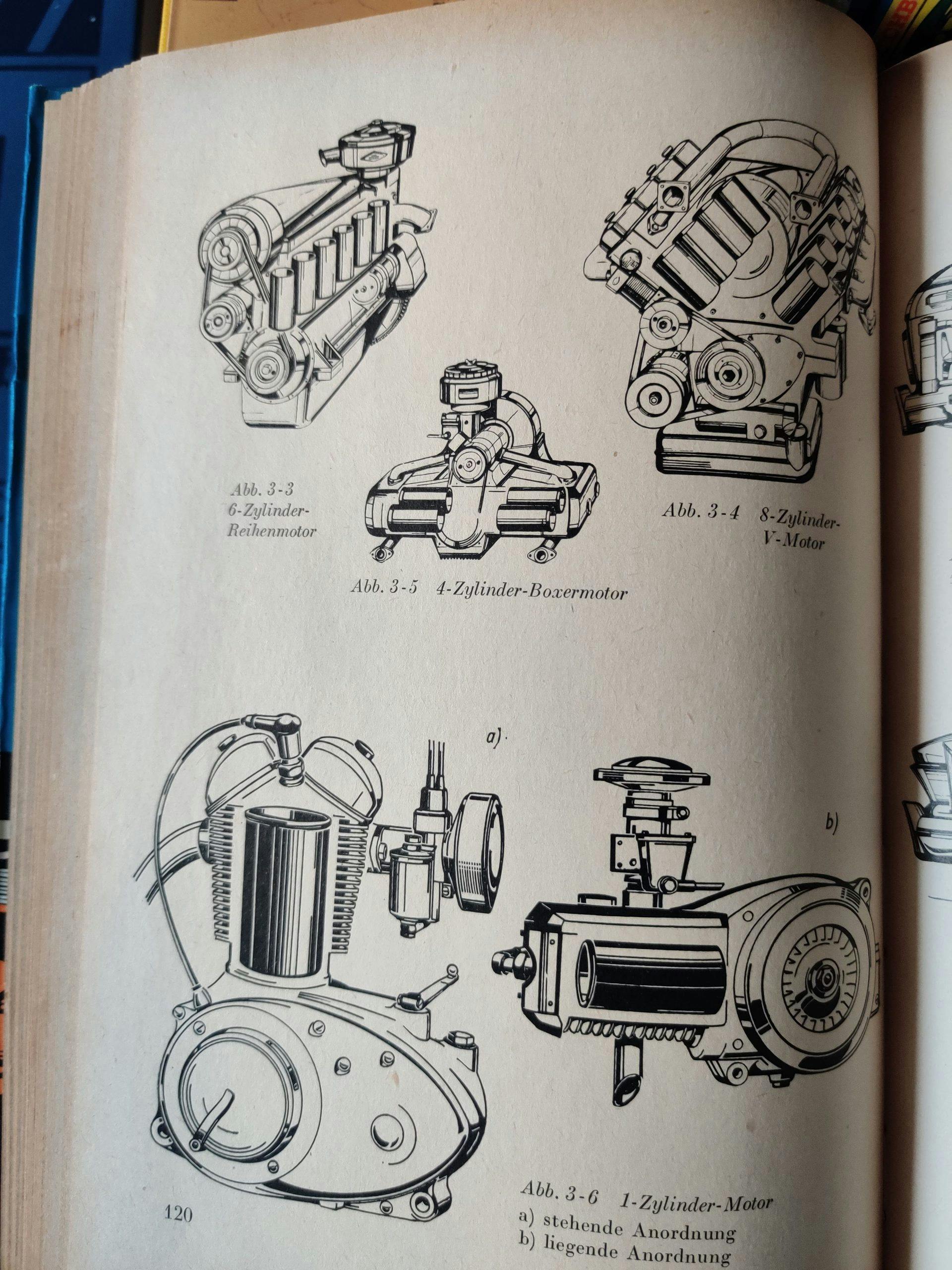

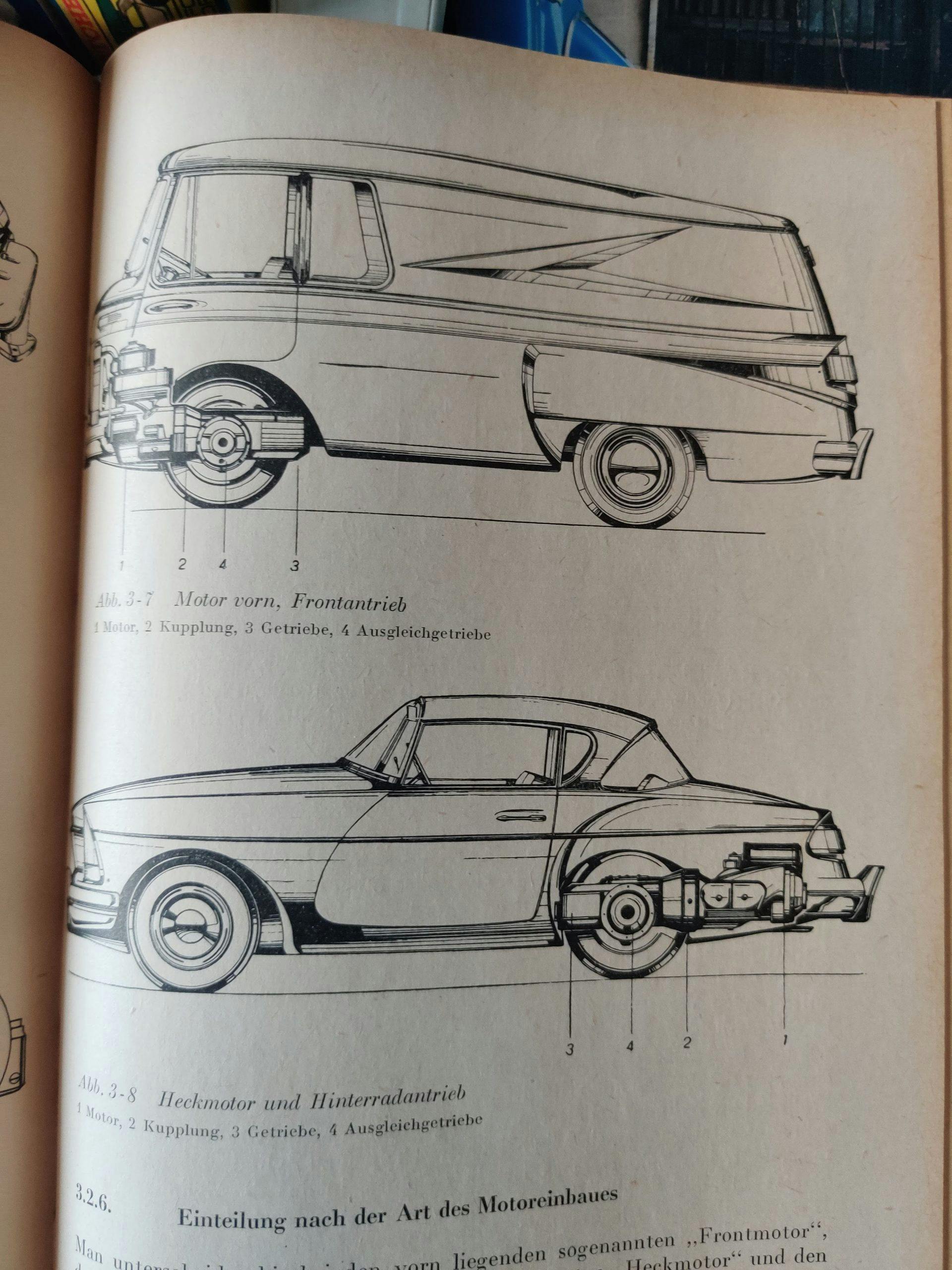

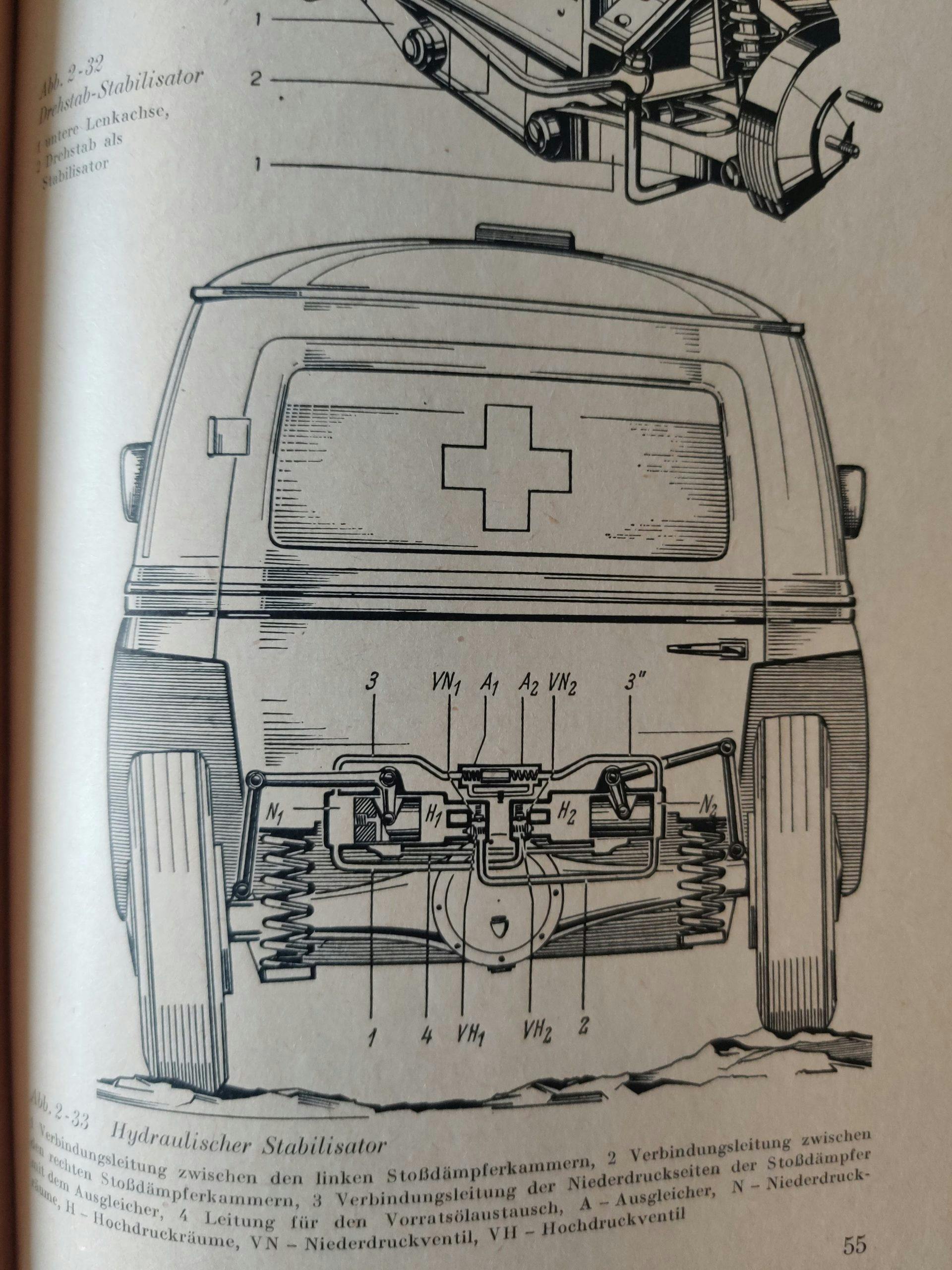

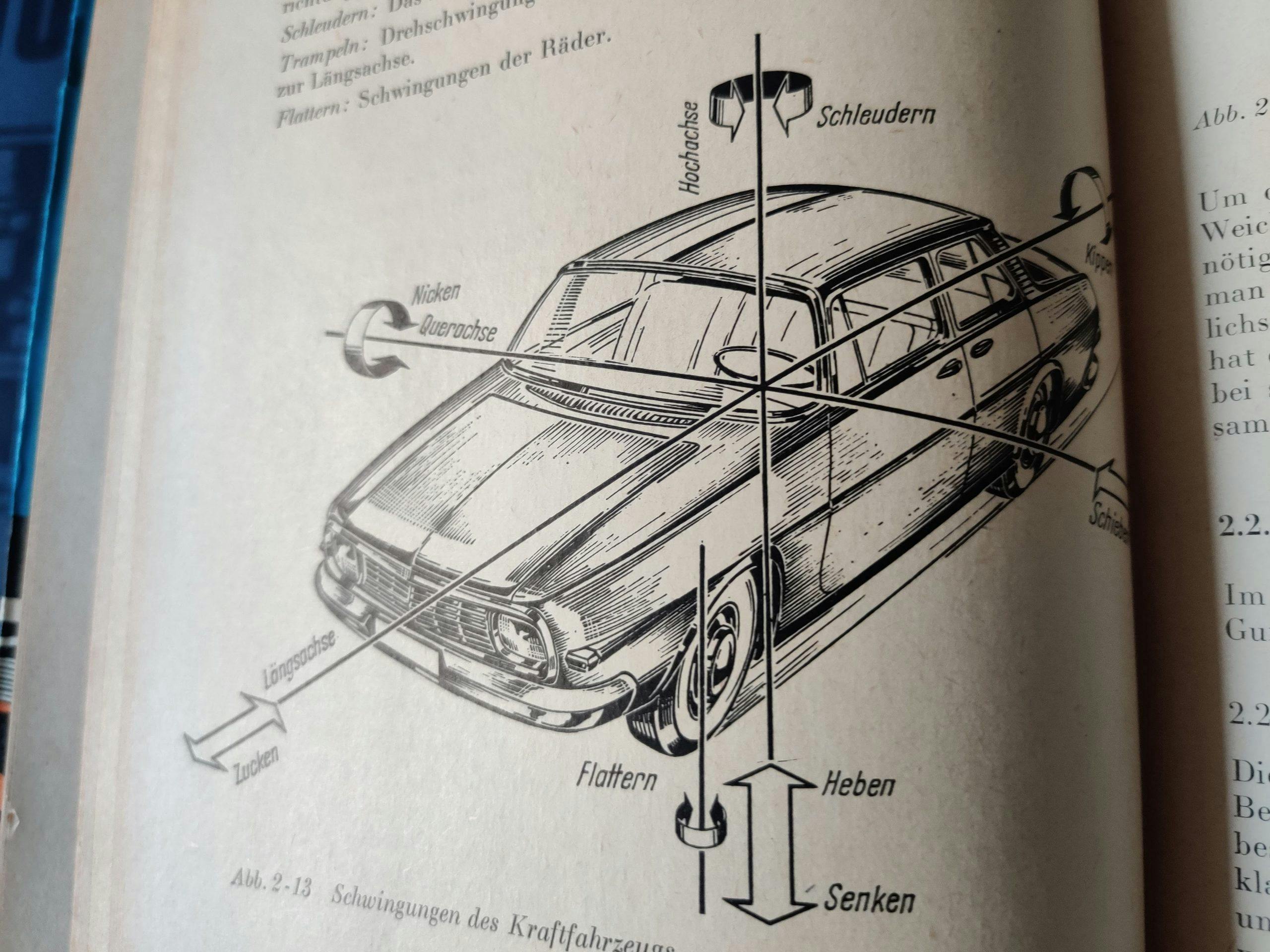

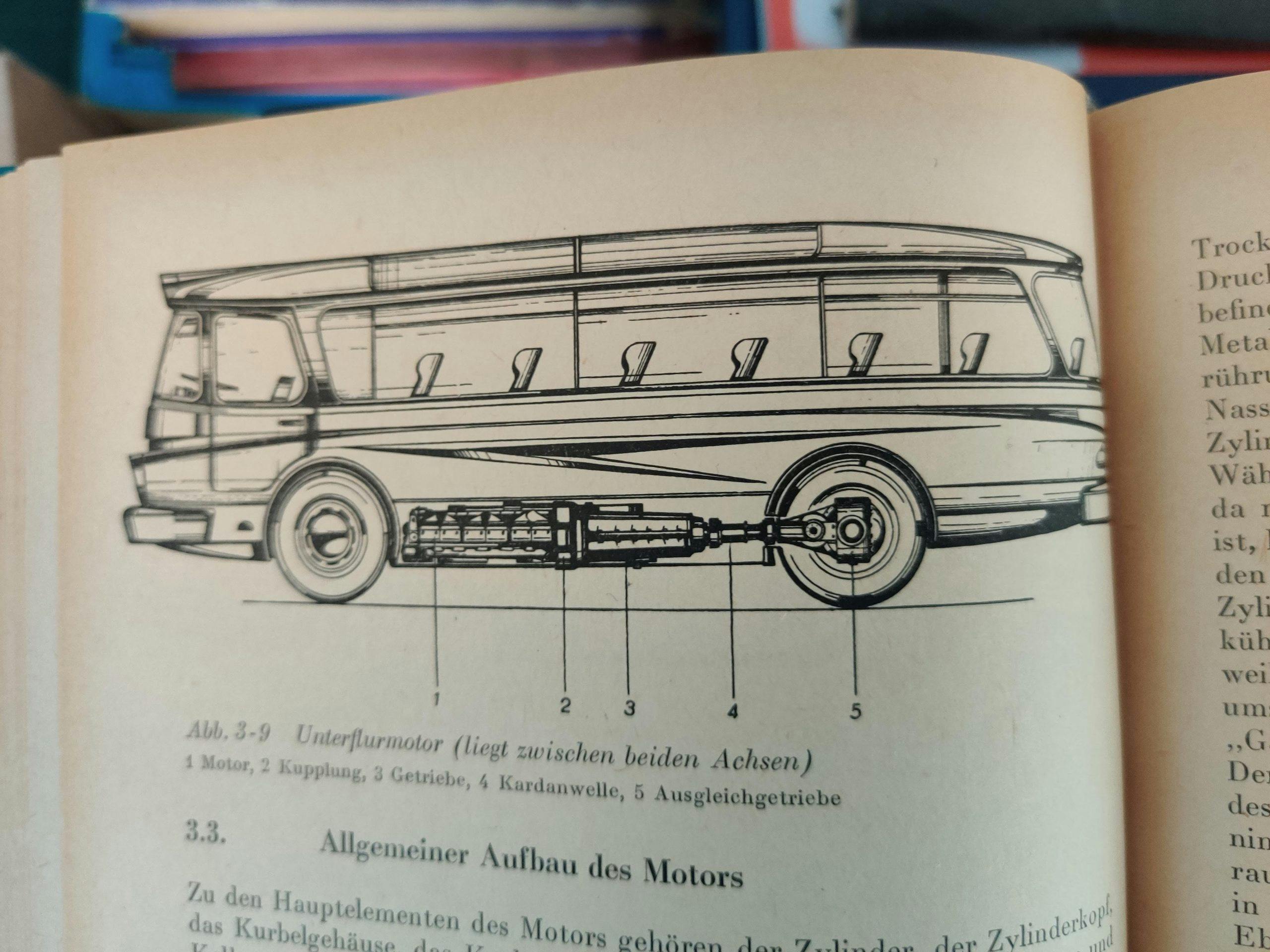

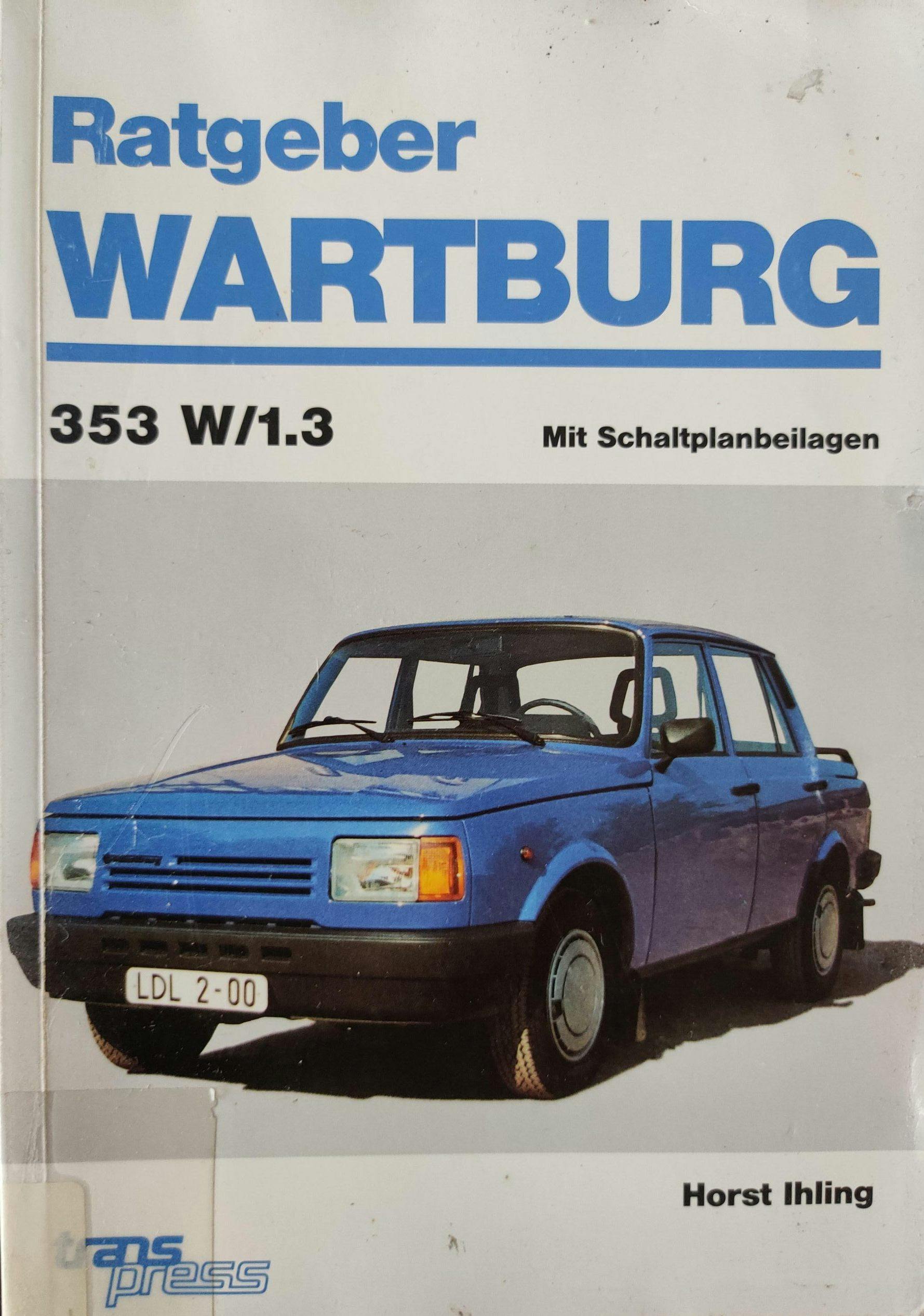

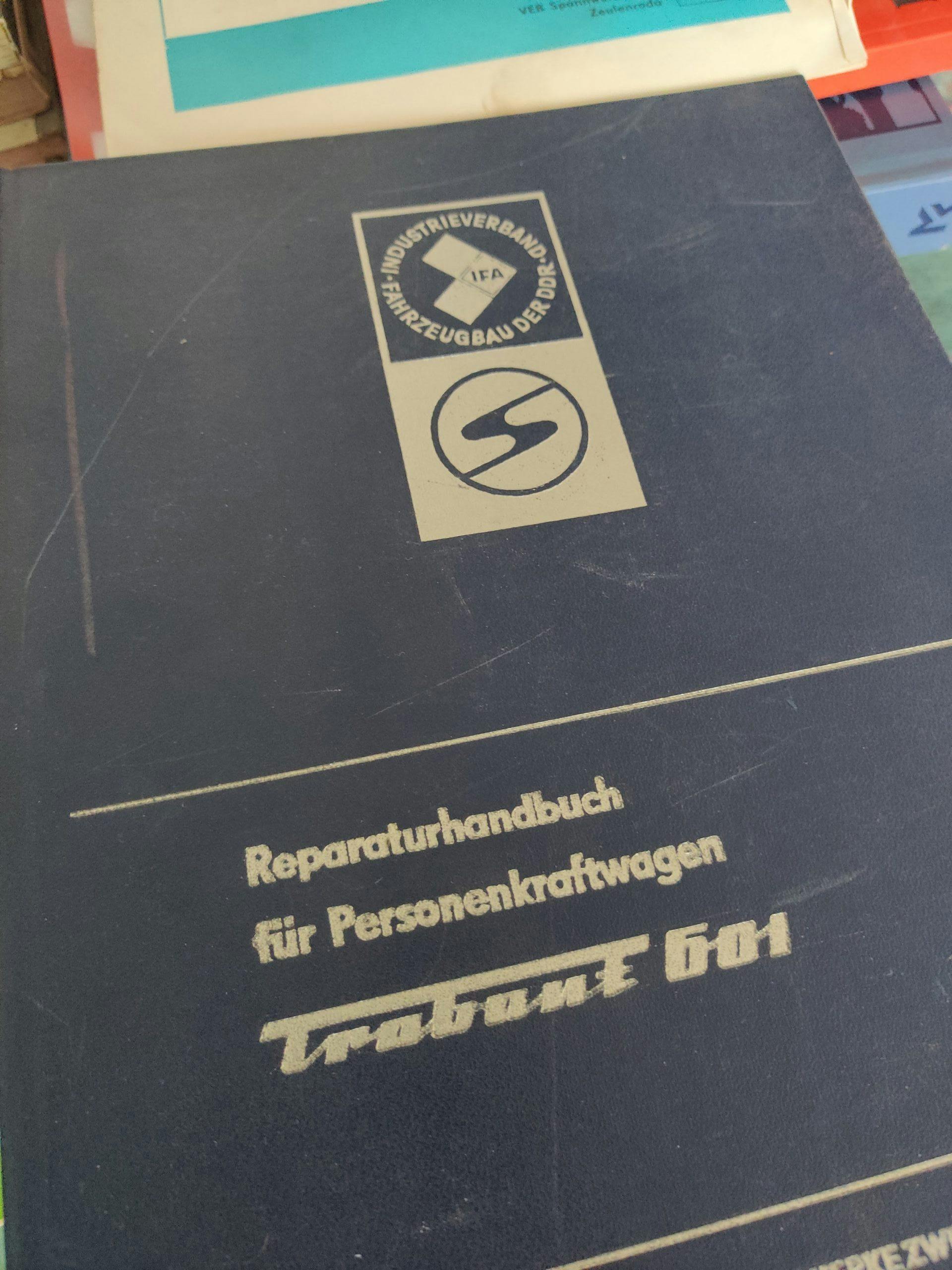

Right now, my display method here in Germany is a simple iron shelf. Several boxes and shelves are, embarrassingly, still in my parents’ attic (next to the matchbox cars). The first book on hand, however, is one of my favorites: Lehrbuch für den Berufskraftfahrer (Learning Book for the Professional Driver) published in East Berlin in 1964. I found this in a flea market in the city’s Soviet quarter. The technical content is quite advanced for what the title suggests. It’s really a Cliffs Notes to the entire automobile, truck, and bus using a a very broad range of progressive technical examples. The best parts of the publication—by a large margin—are the illustrations within. Each vehicle is fictitious and meticulously drawn as conjured up by the illustrator. From the relevant details of how a two-stroke three-cylinder motor works (pertinent to Wartburg and Barkas ownership) to the driveline layouts of an imaginary finned bus with a mid-mounted flat-eight, it’s all here.

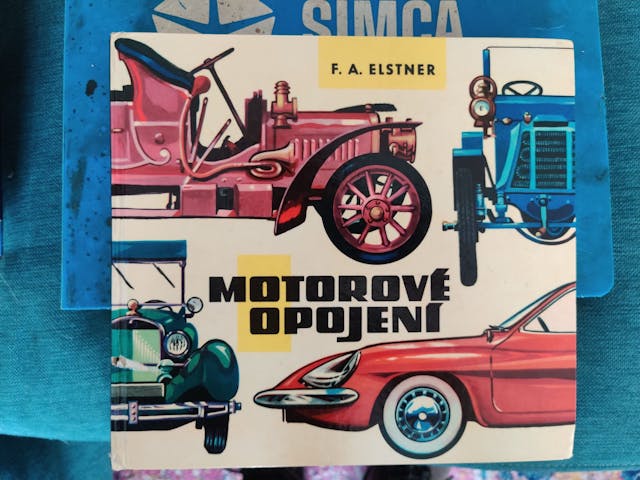

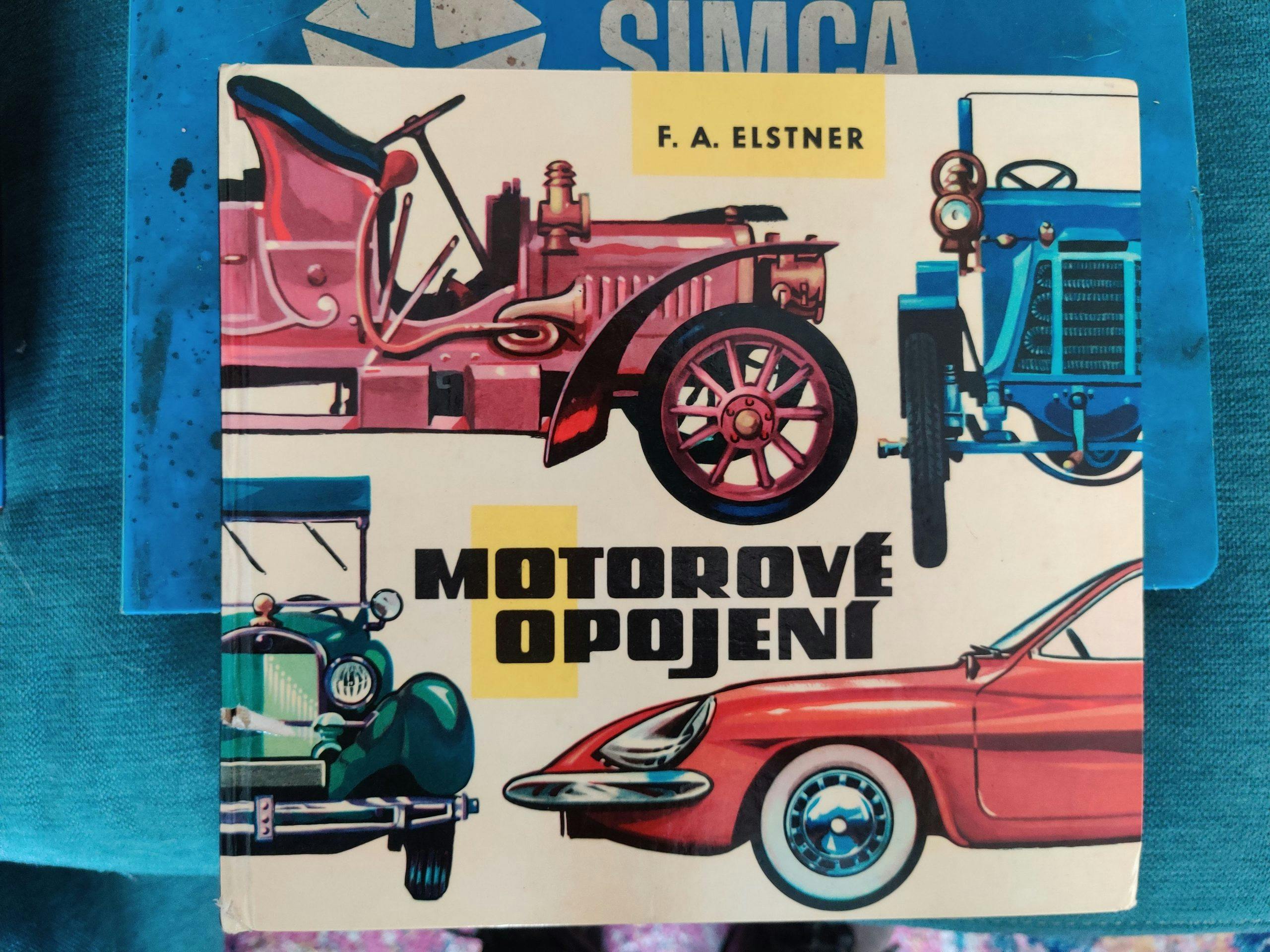

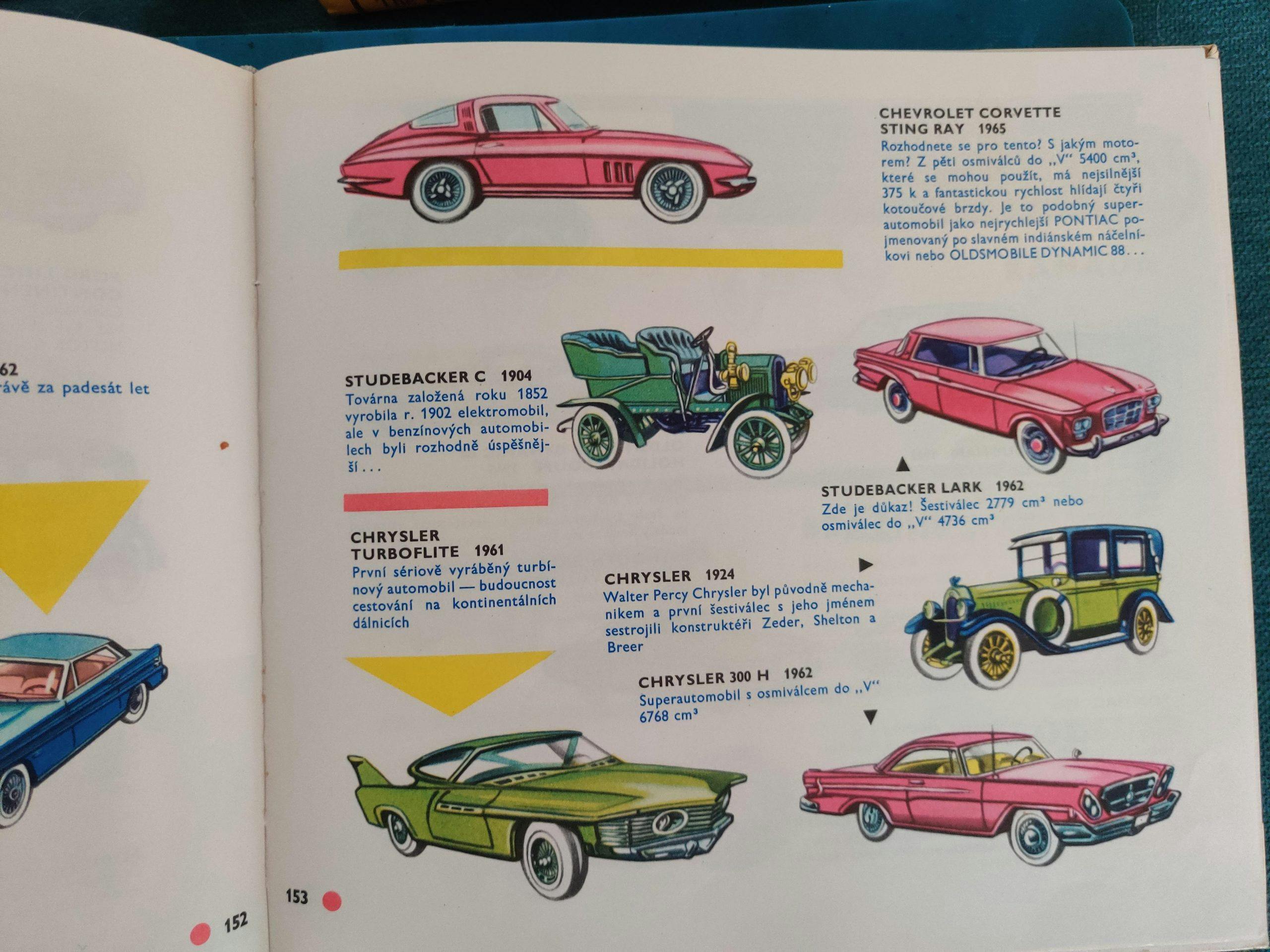

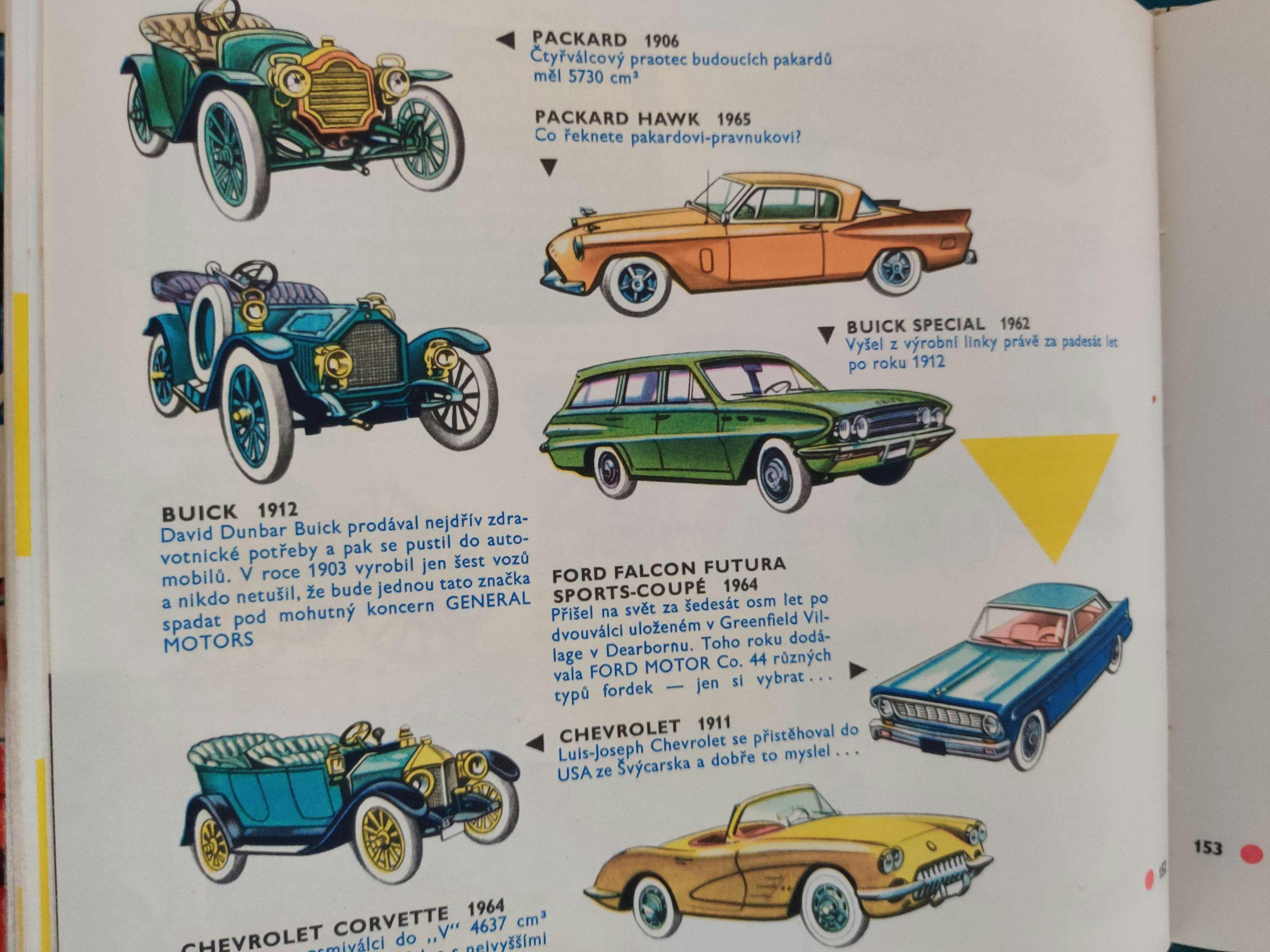

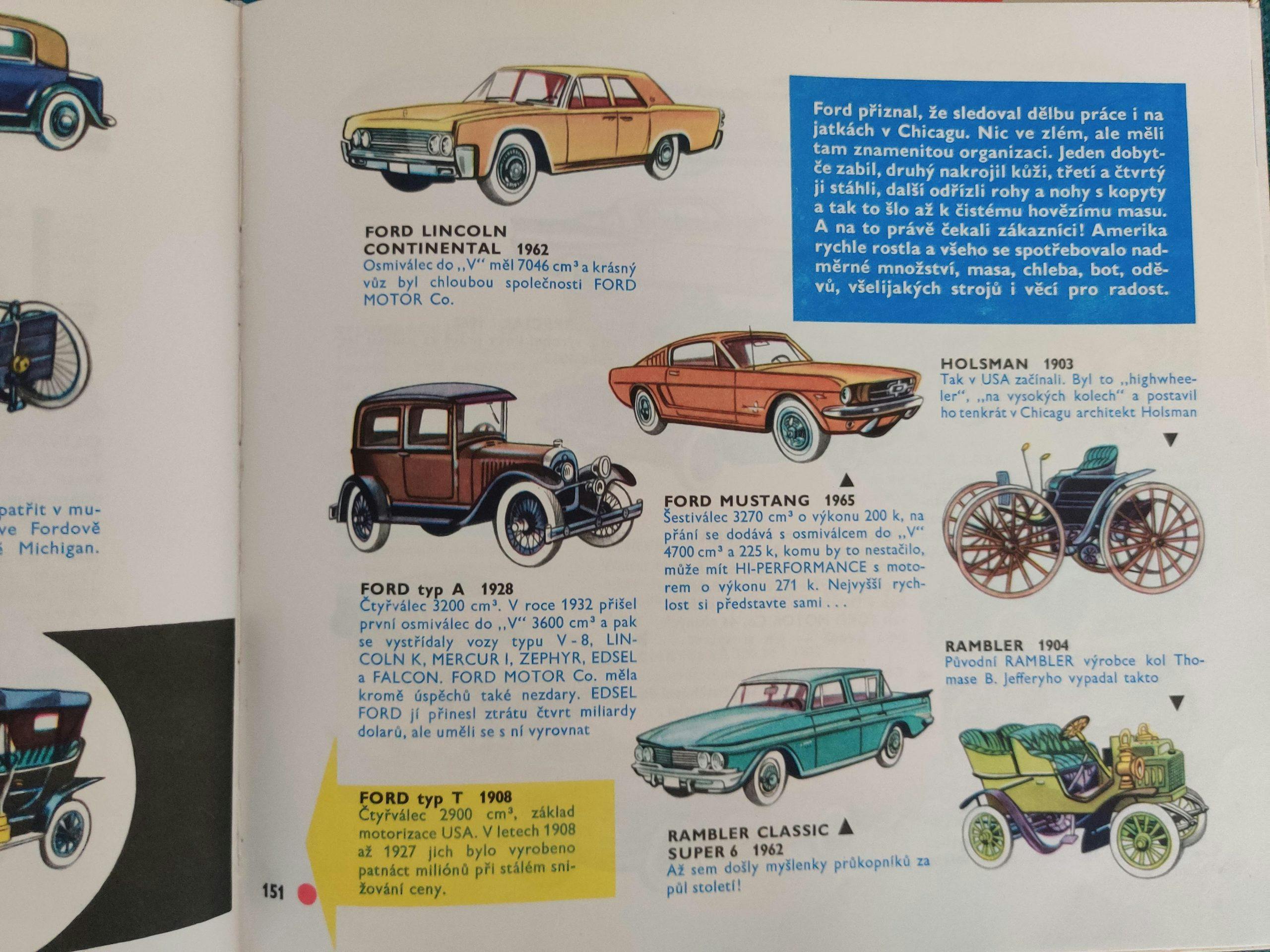

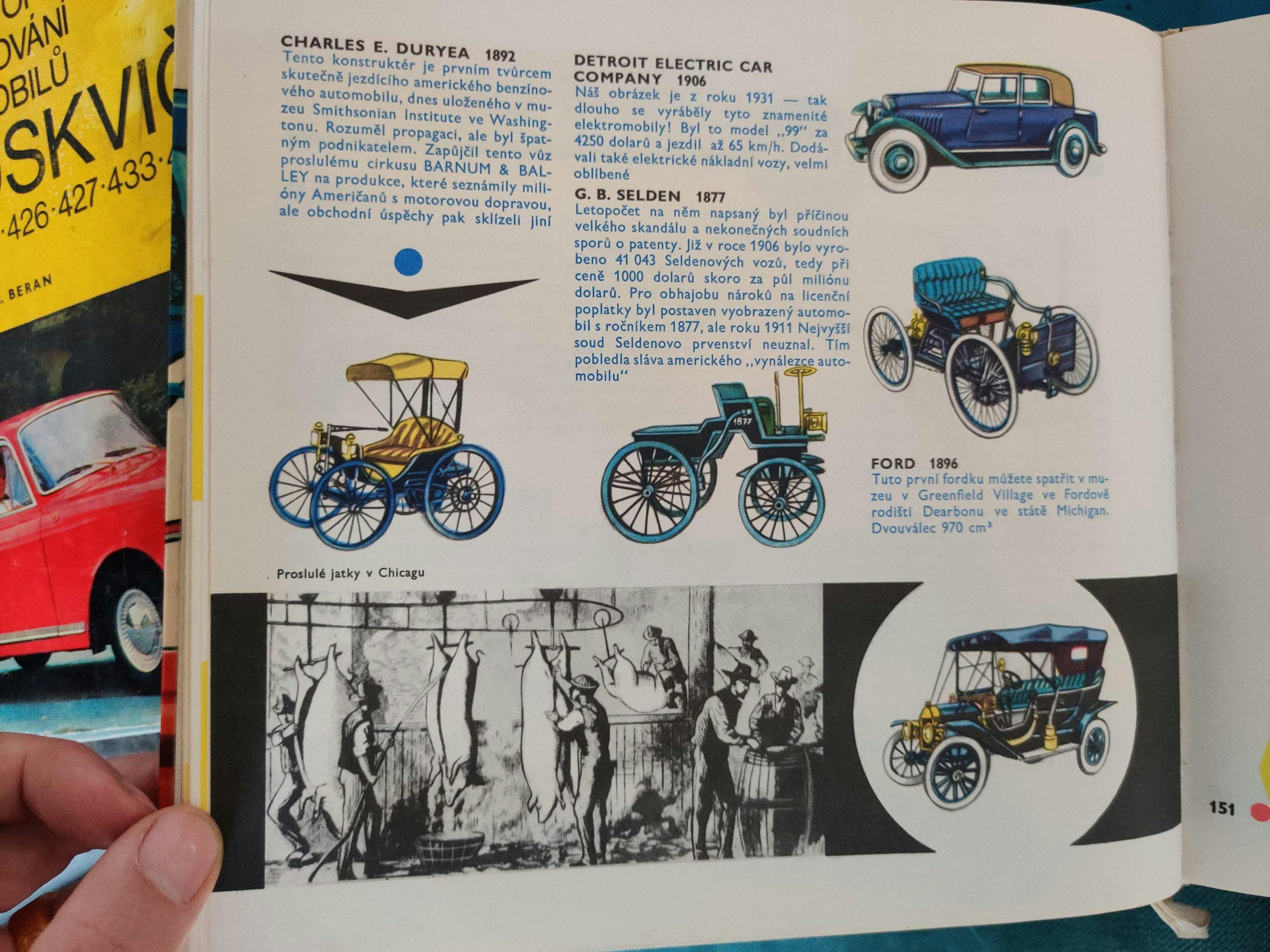

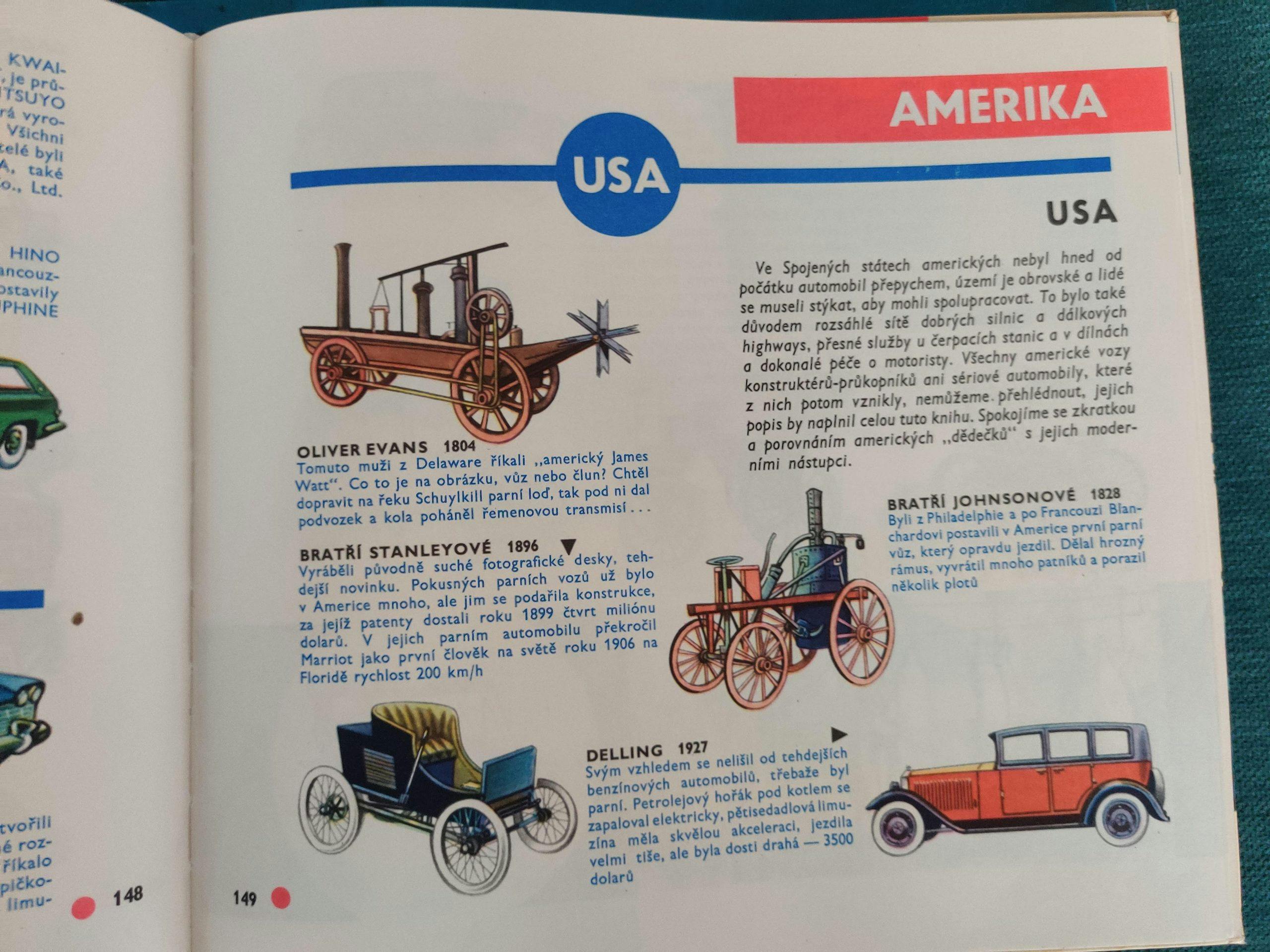

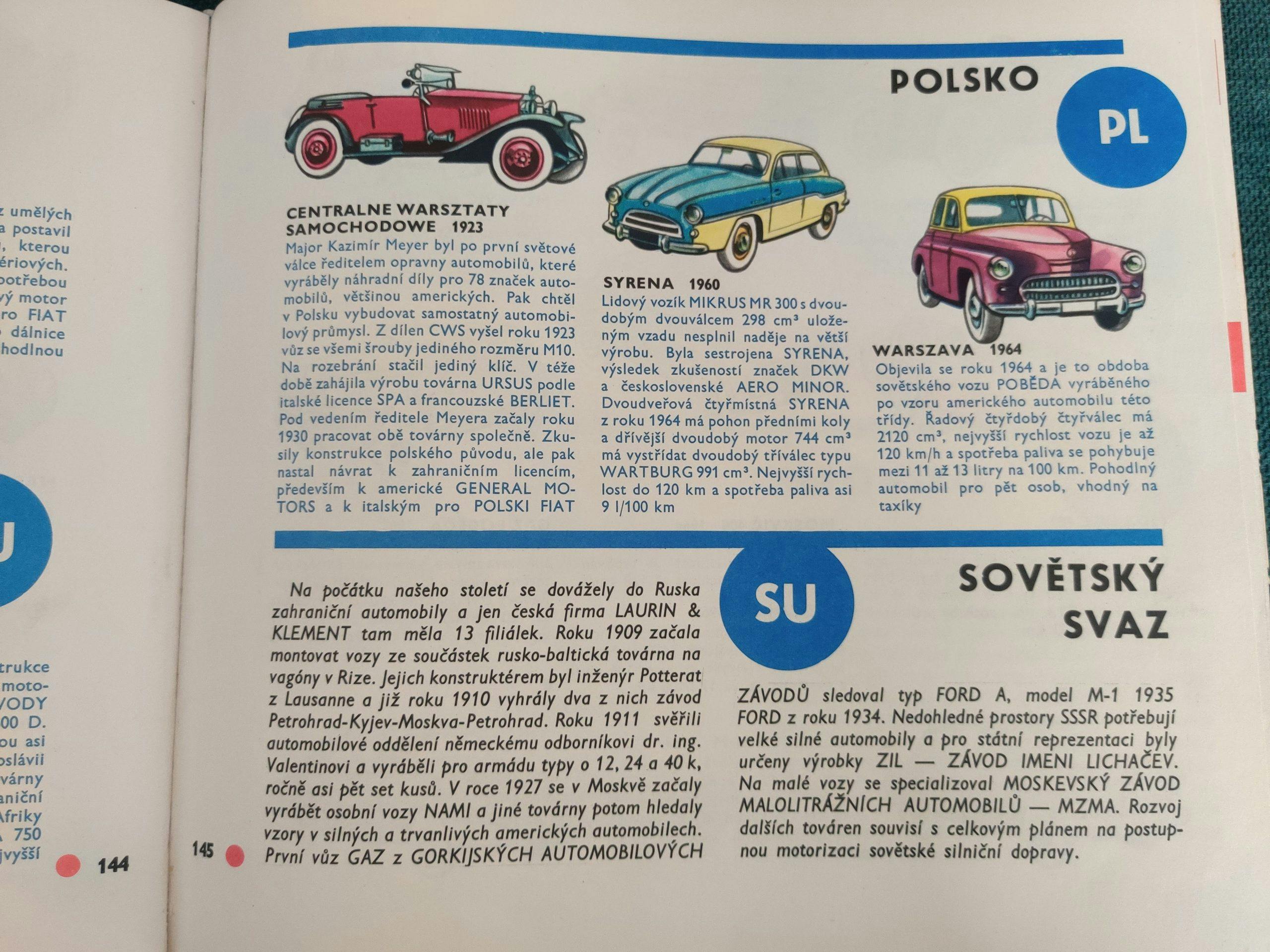

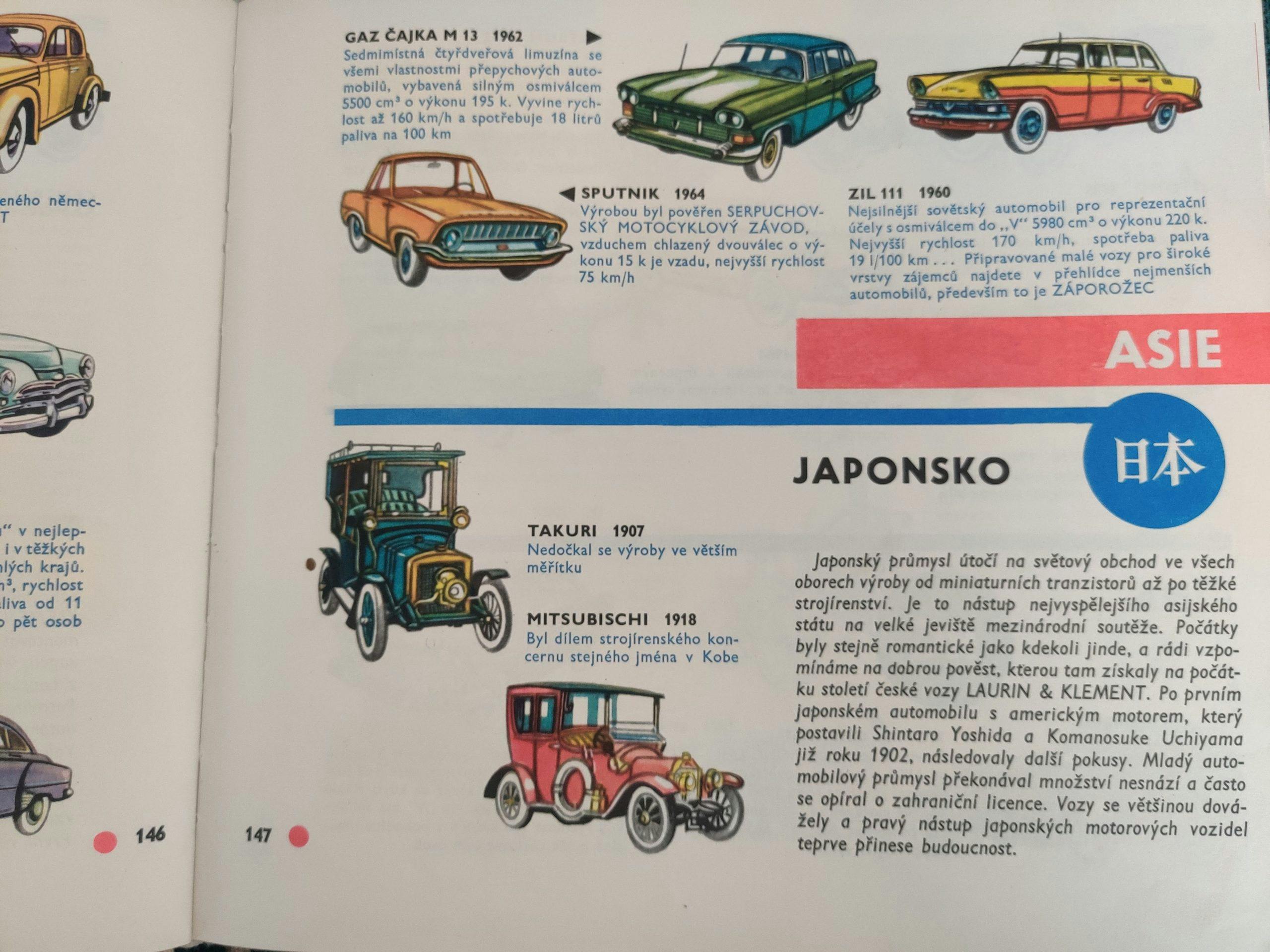

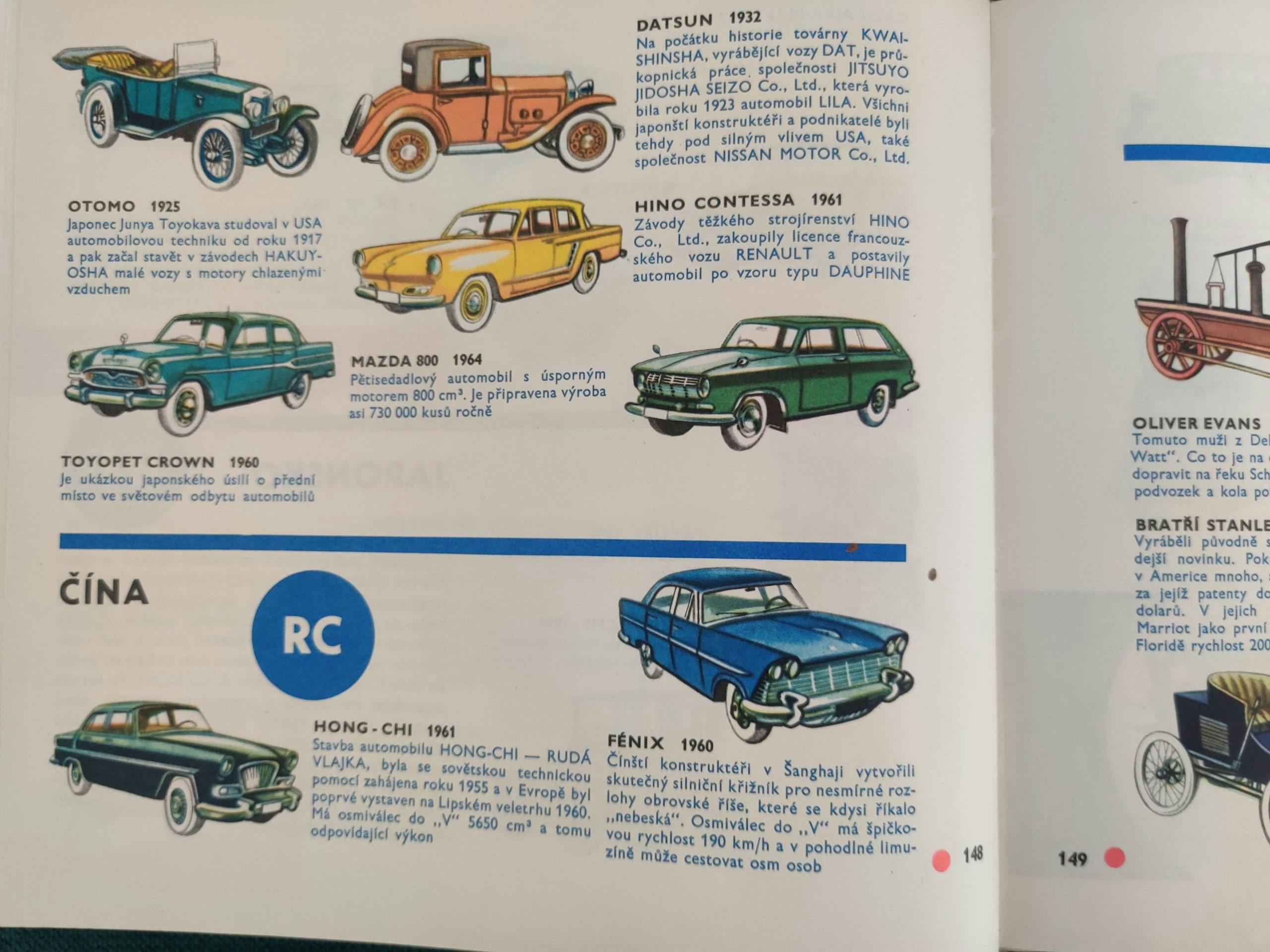

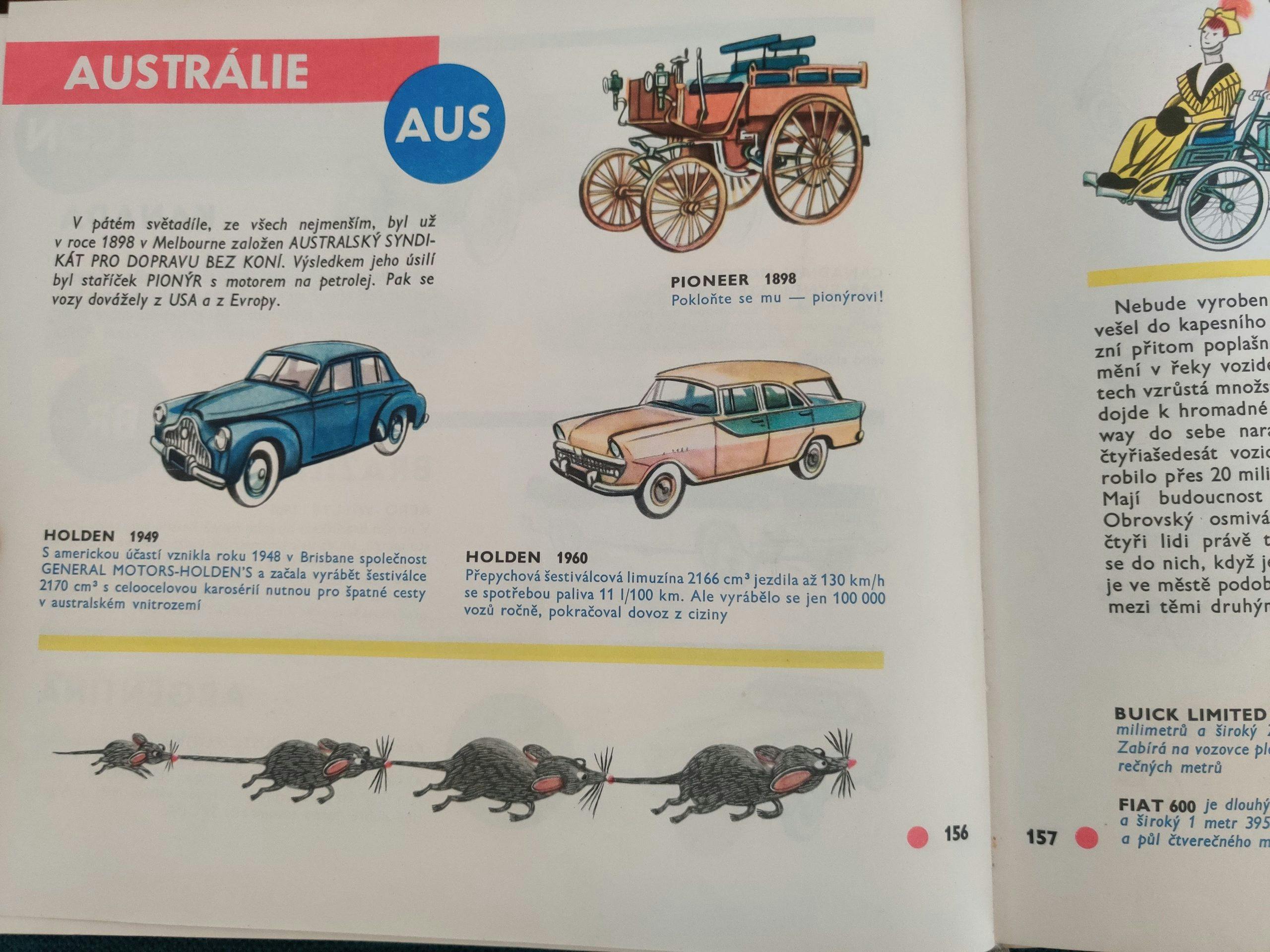

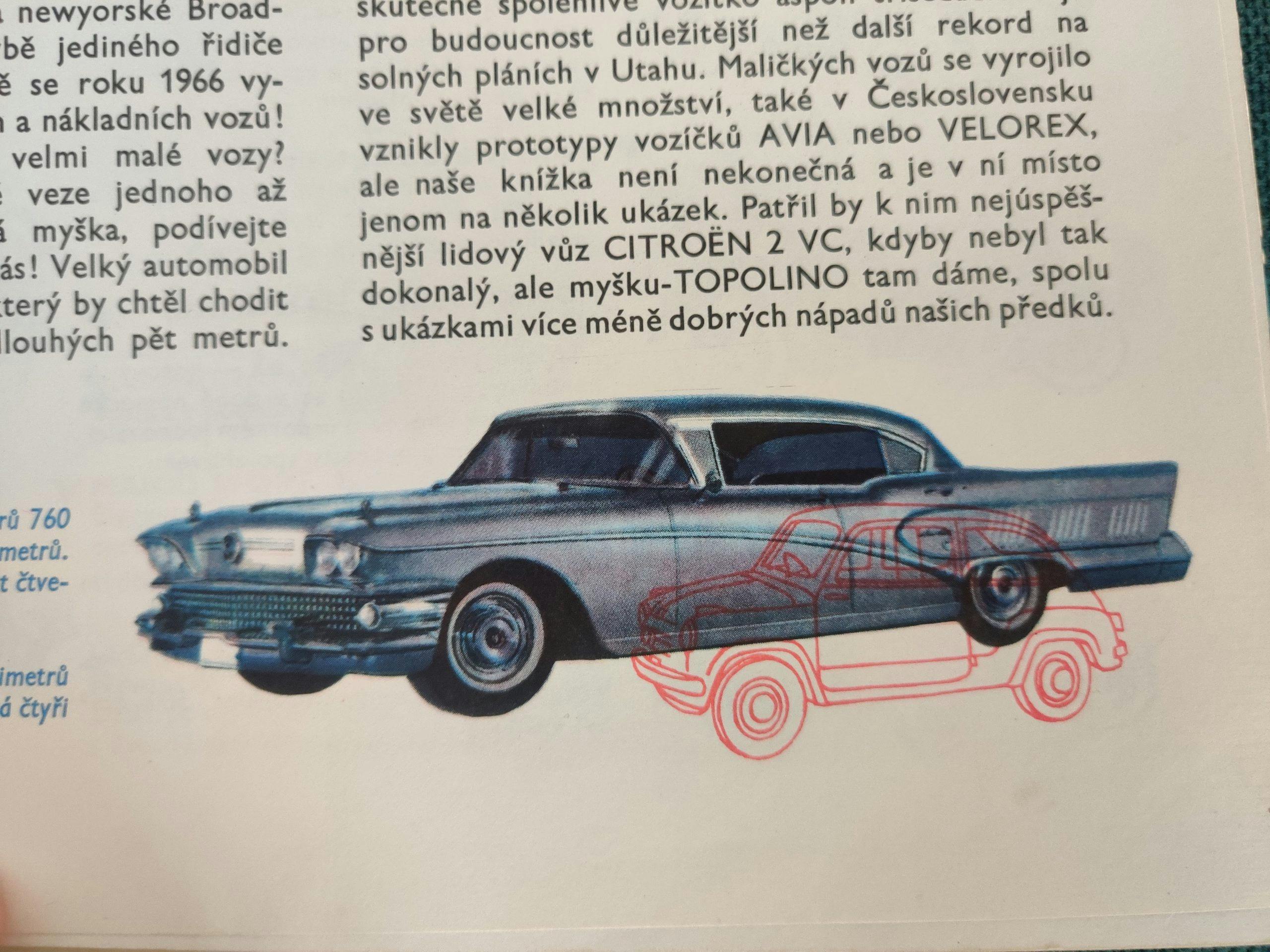

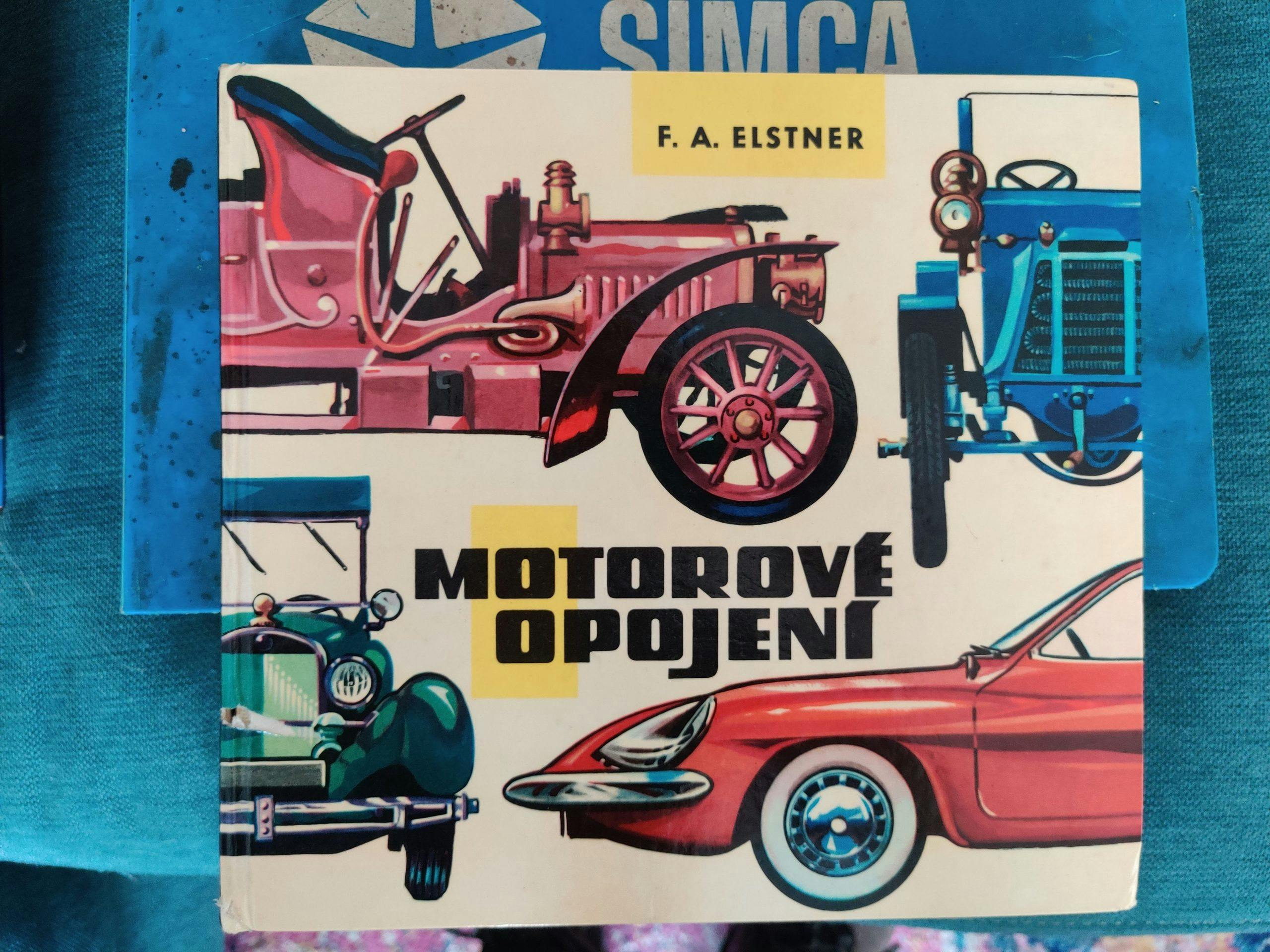

Next up is a book from Prague circa 1966, called Motorove Opojeni (Motor Intoxication). I found this by wandering into the warehouse of an online-only bookstore in Prague. After a few minutes of help from an employee I was browsing their collection on a desktop PC and easily filled my cart. It’s a bit tough to understand the target audience for this book, given the number of illustrations of child-like characters involved. Either it’s a study book for Czech MENSA-4-Kidz or some odd folk art preference. Either way, the content is bonkers. Especially fascinating are the pages showing the Cars of the World, including some practically un-Googleable Chinese stuff and an unusually progressive selection of American iron, considering the times. Also worth a look is the broad Japanese section.

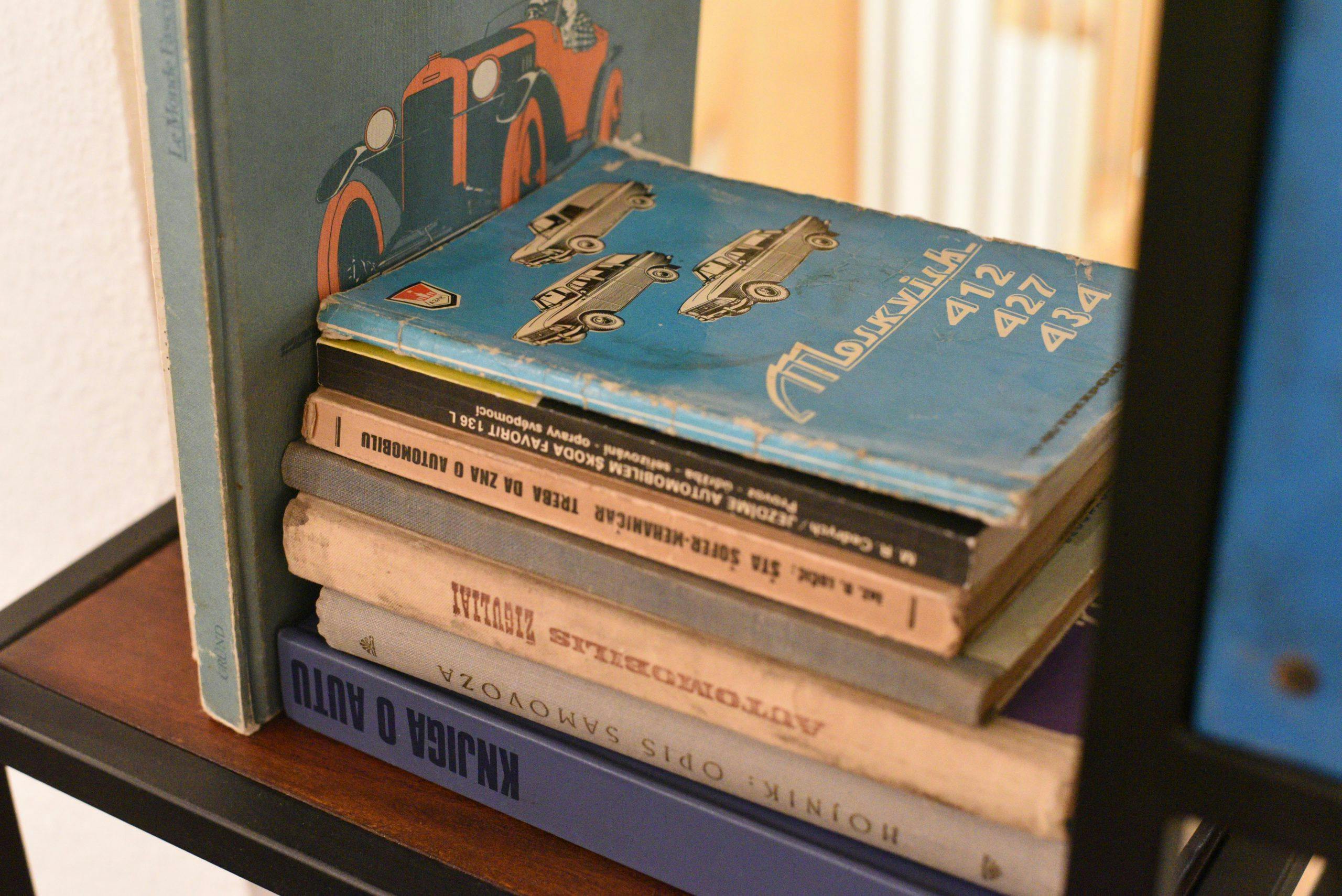

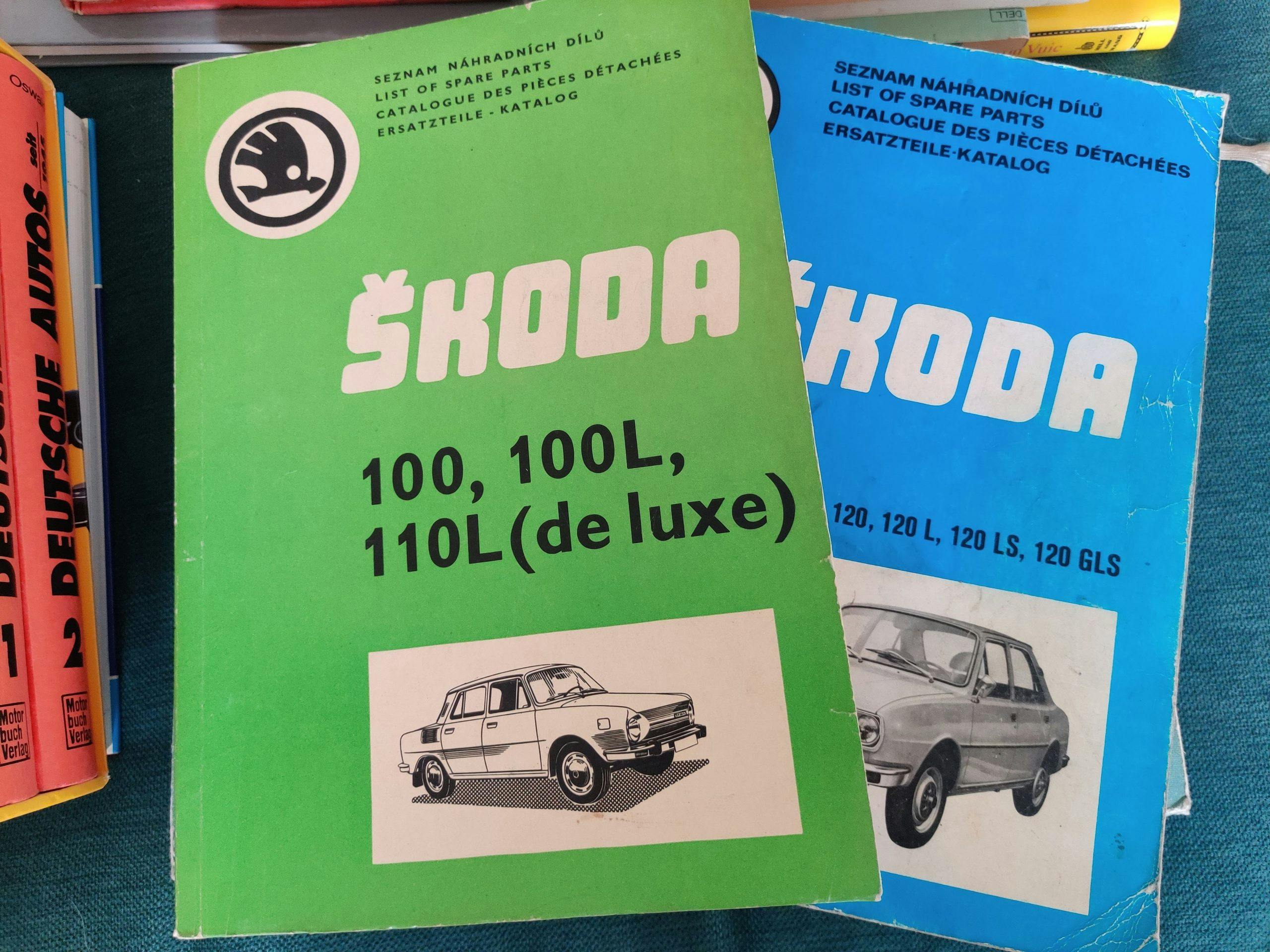

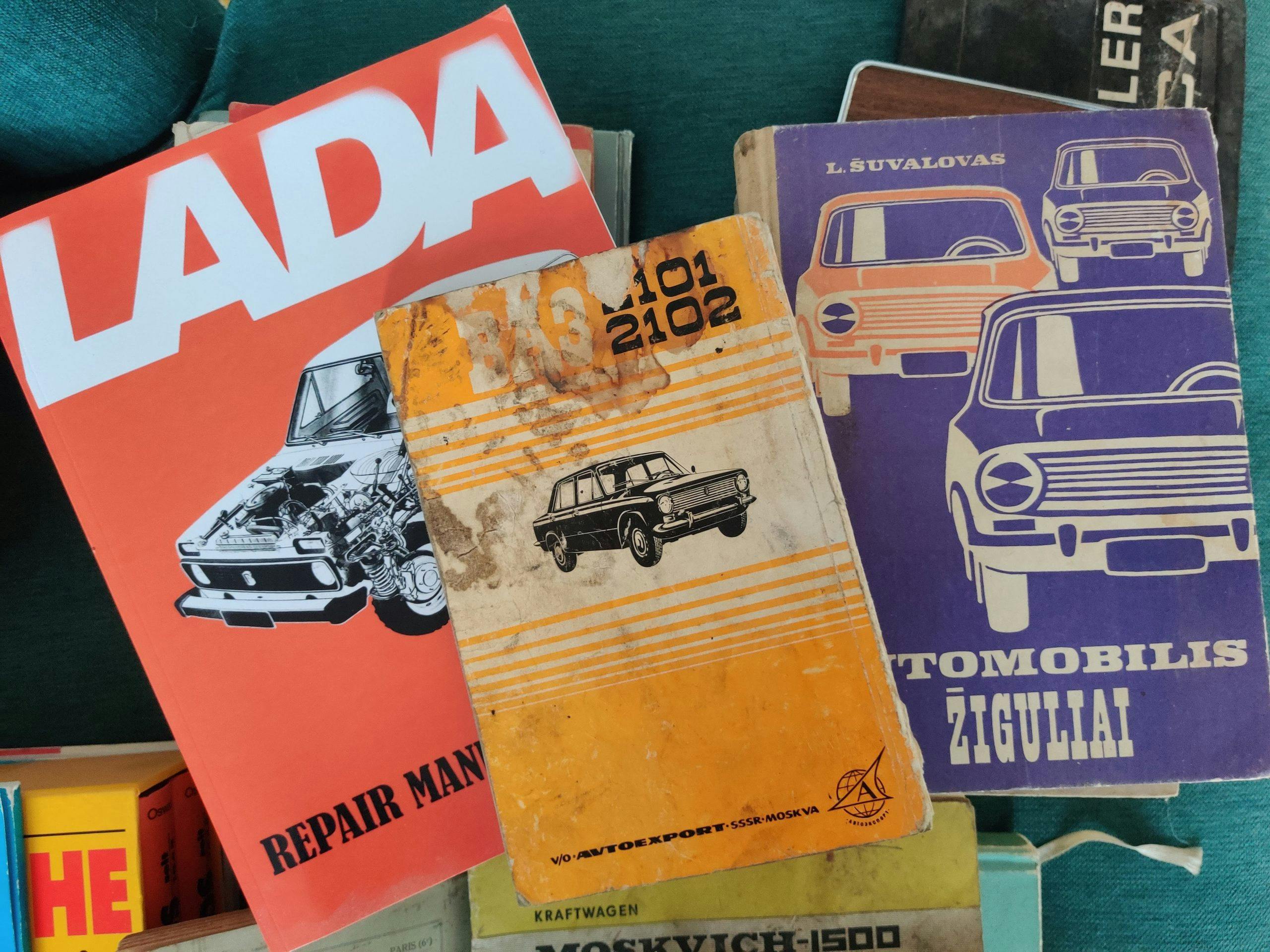

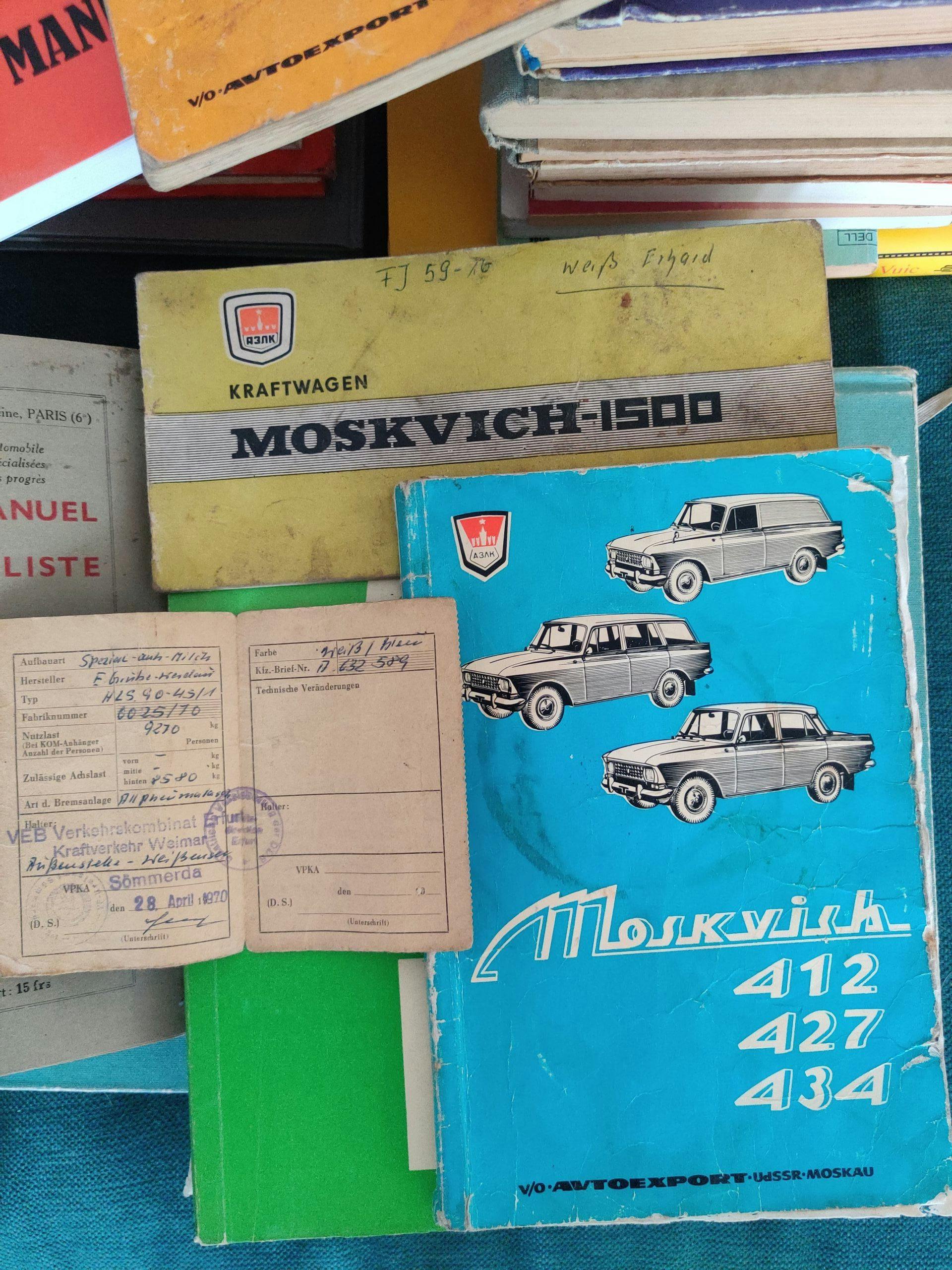

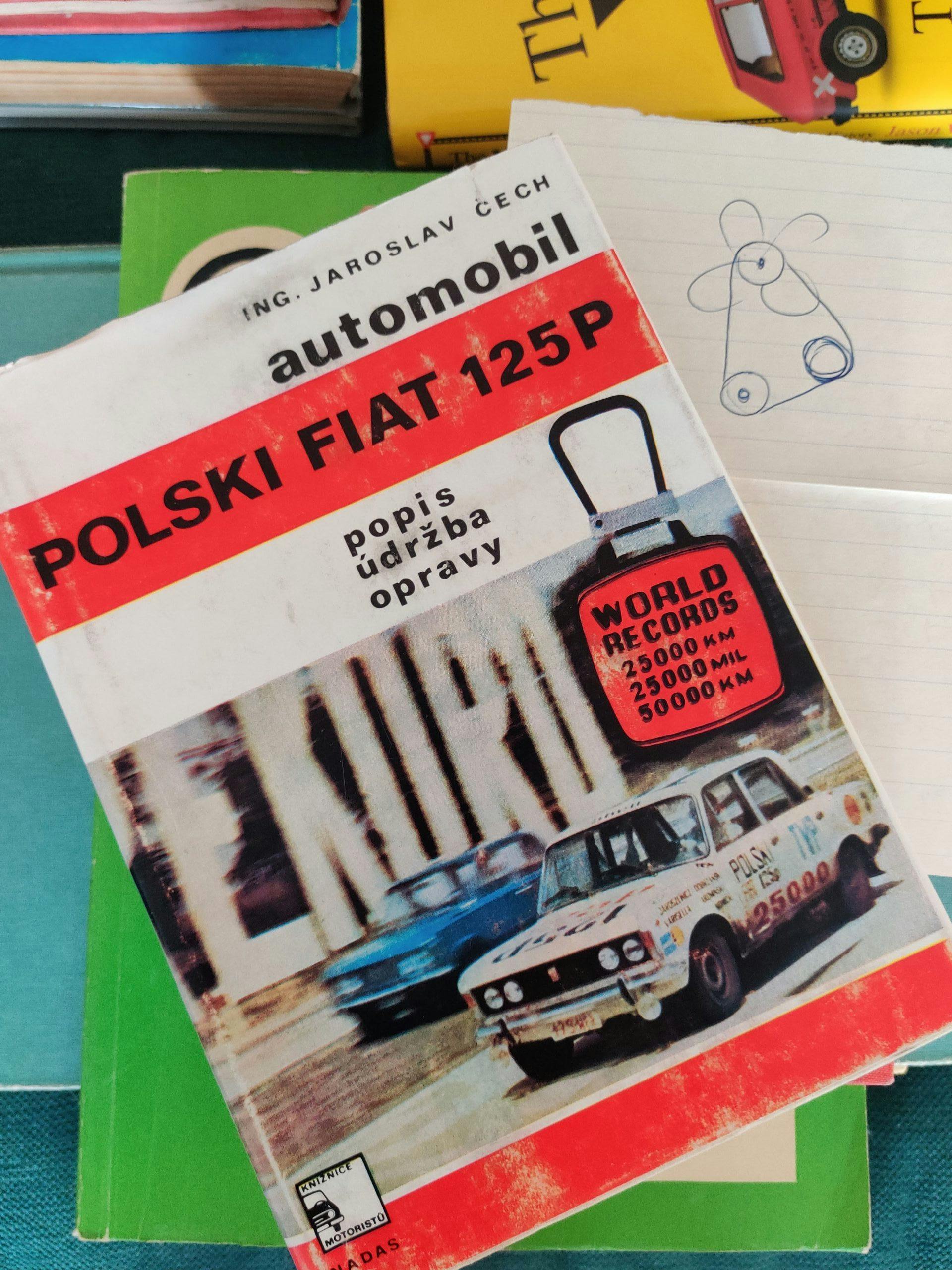

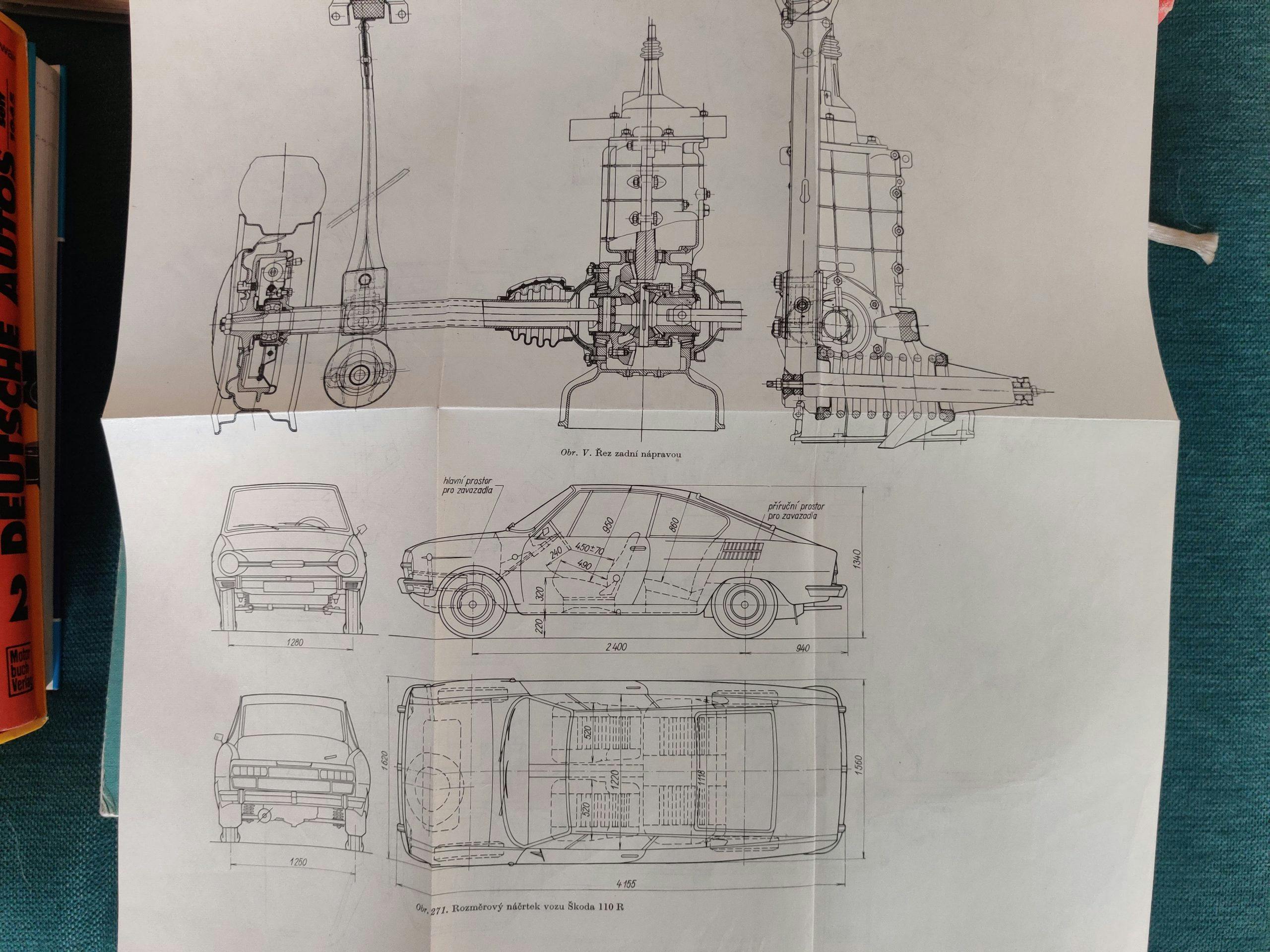

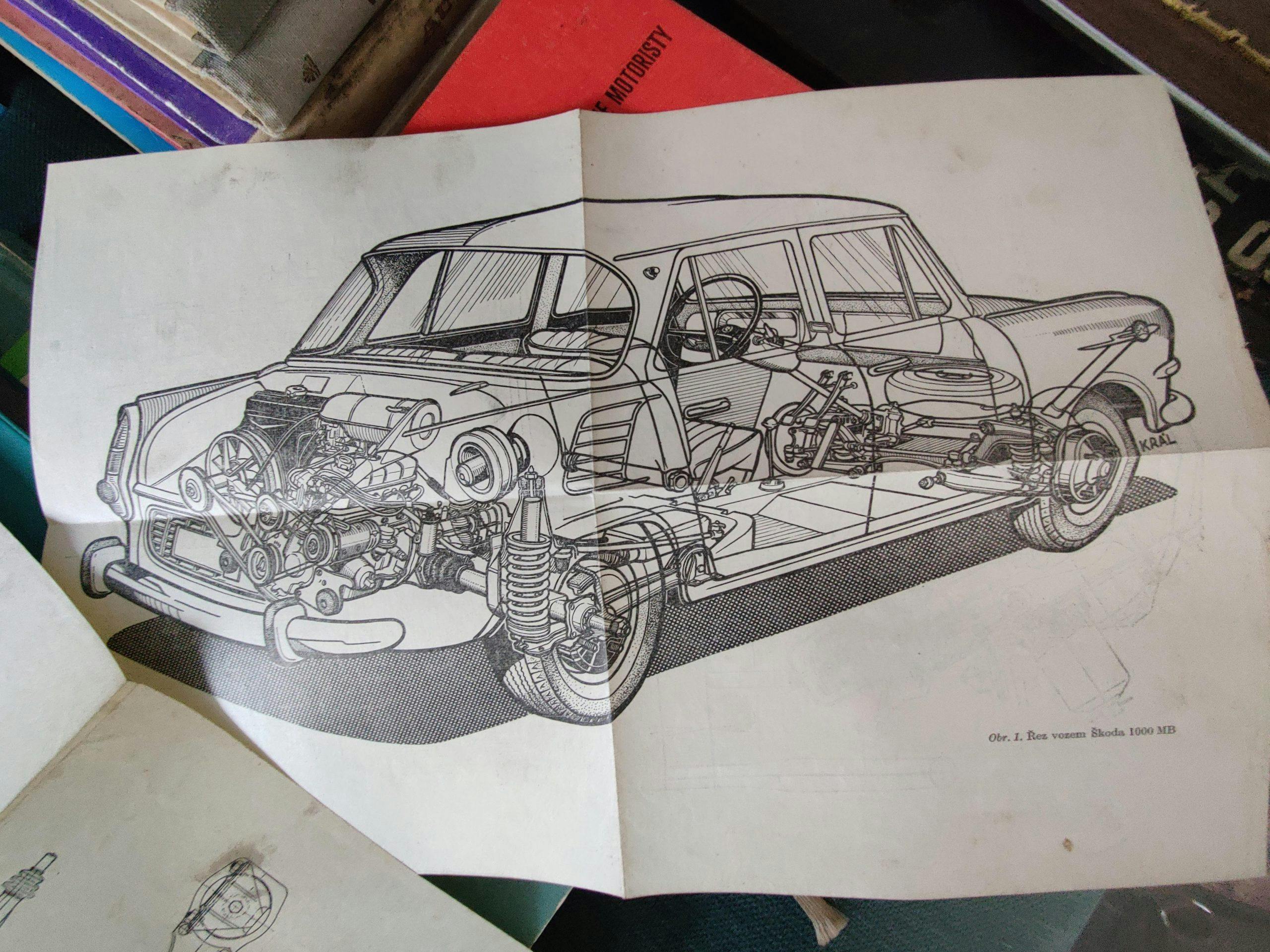

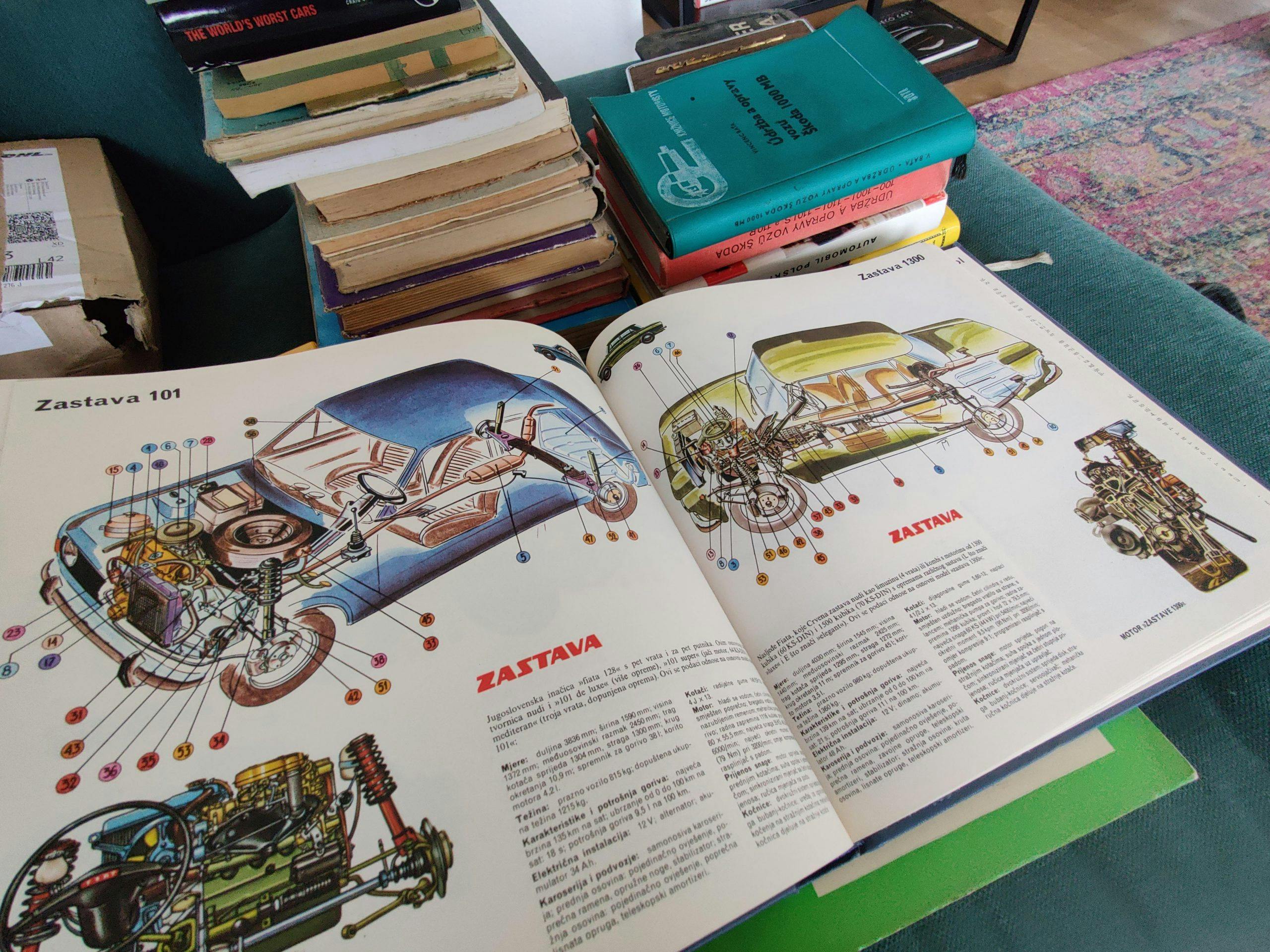

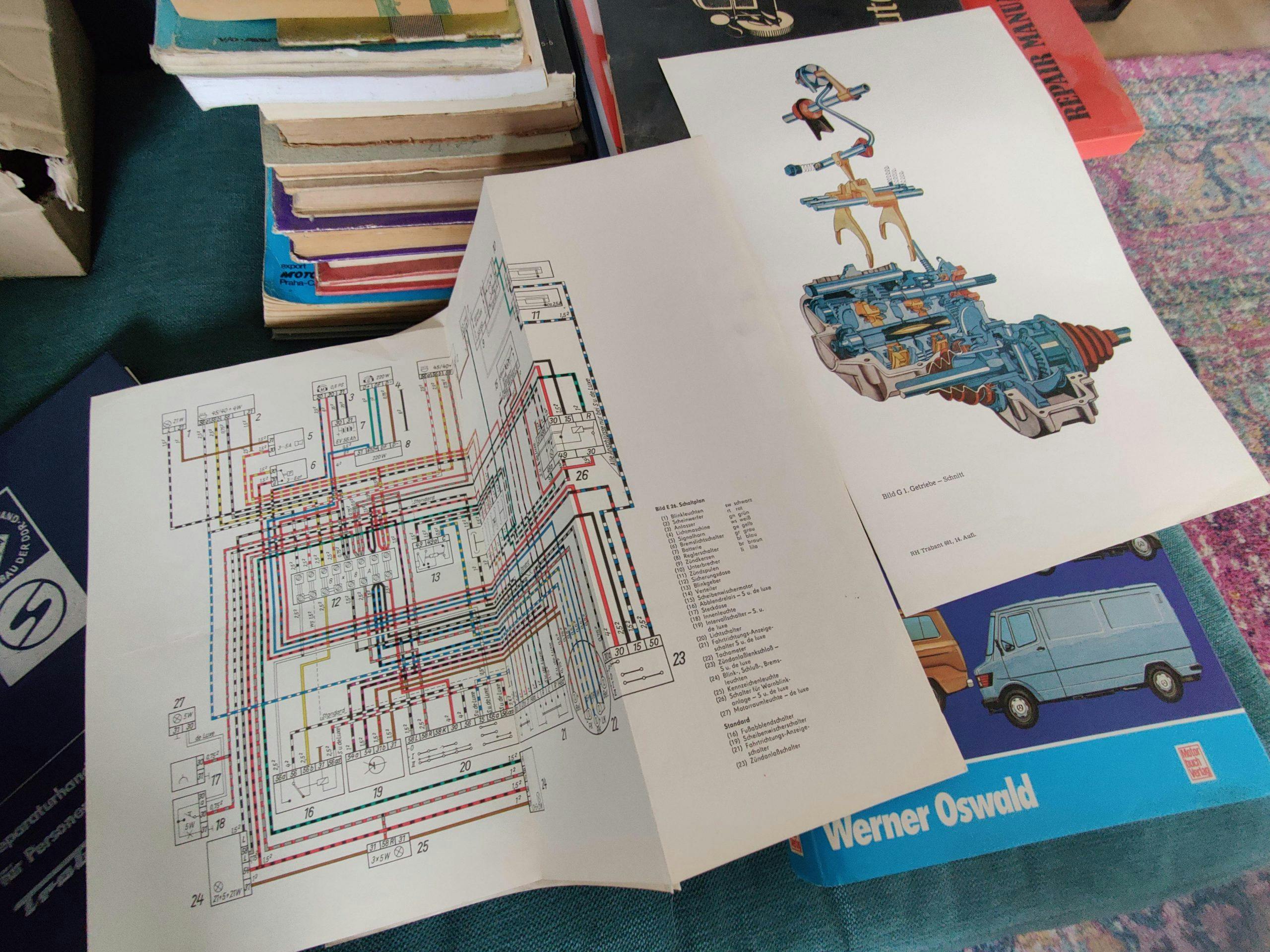

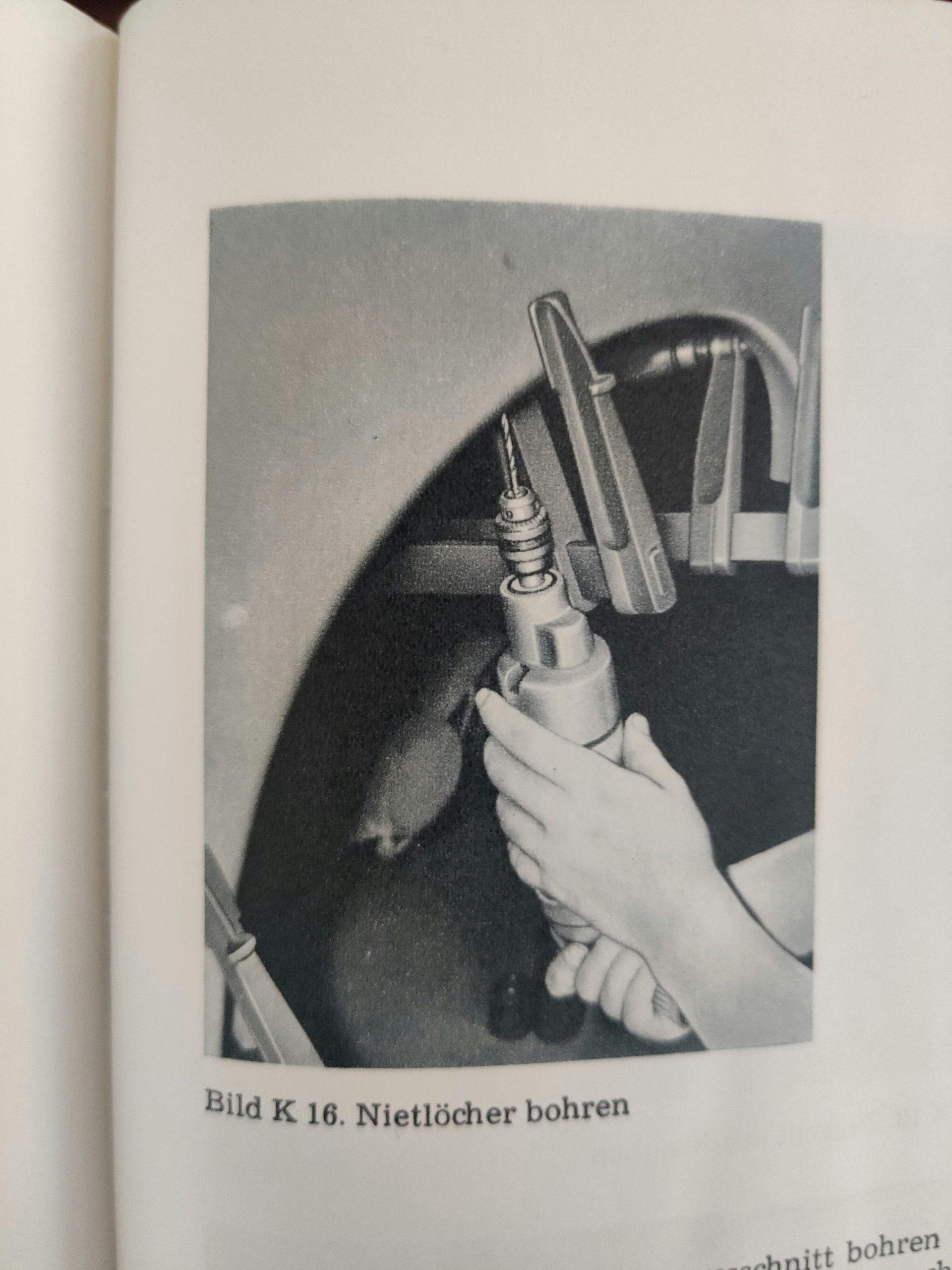

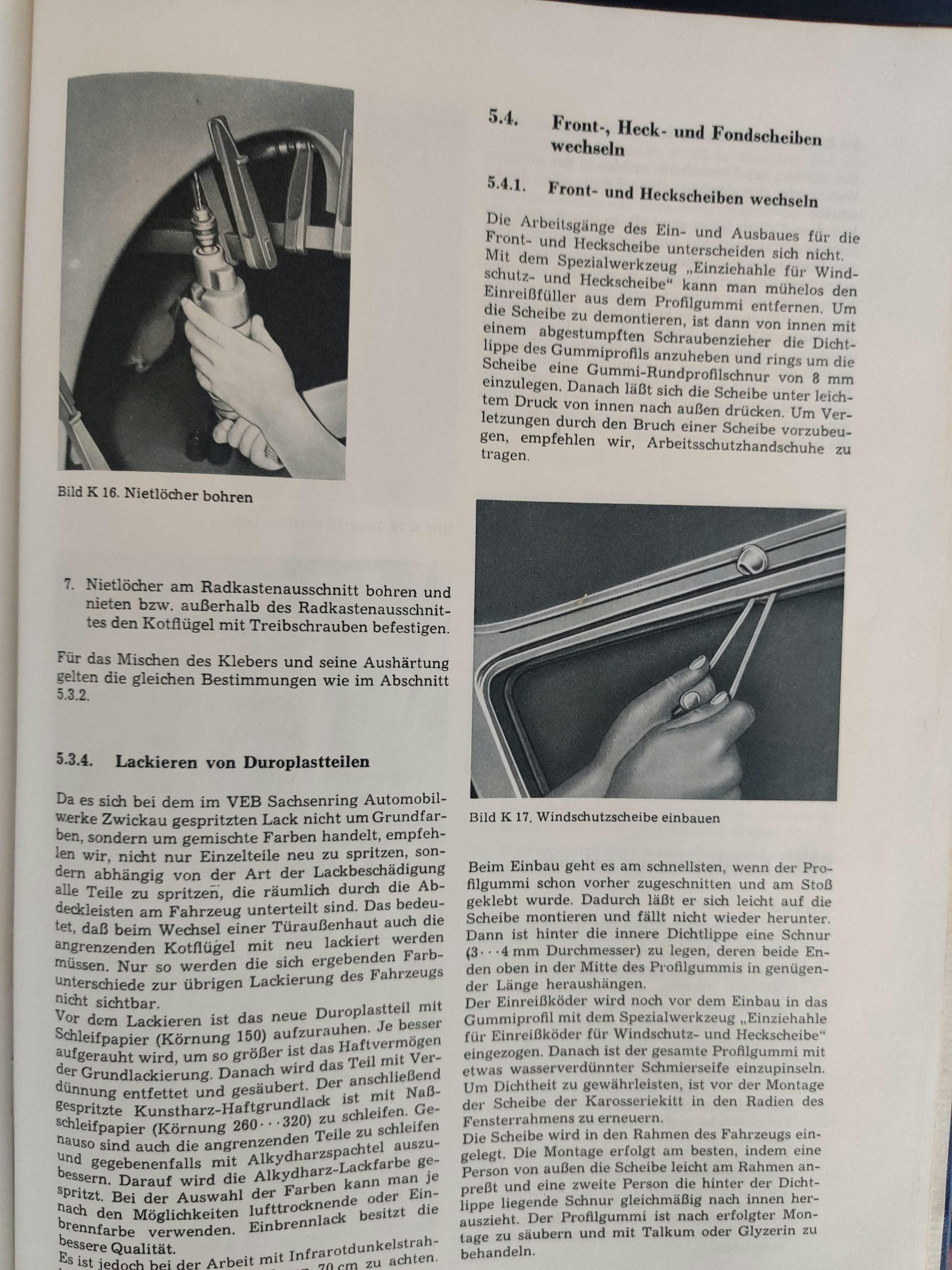

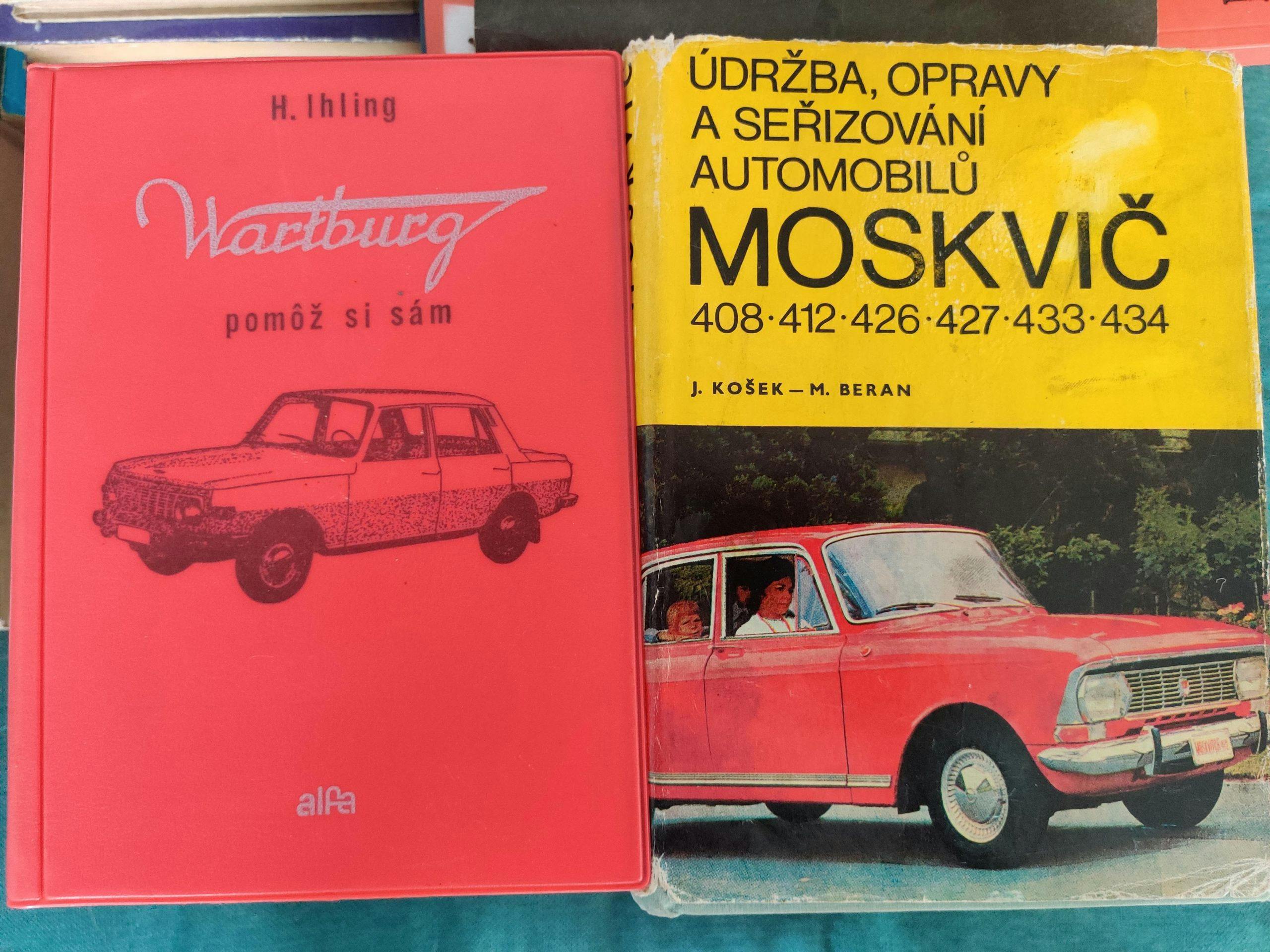

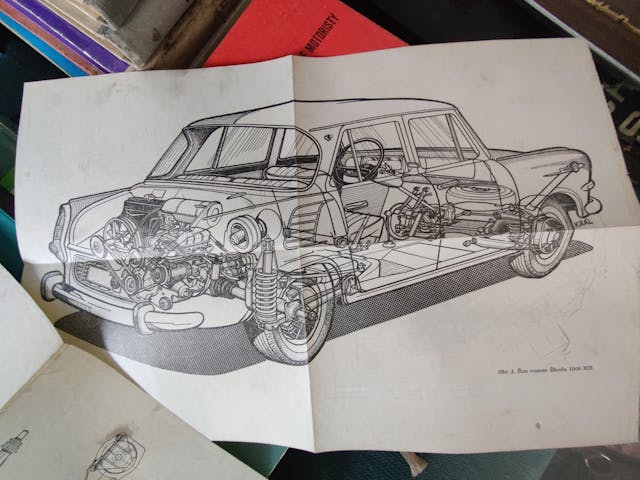

On a separate trip to Prague, some years earlier, I had accidentally withdrawn about $600 worth of Czech Korunas from the hotel ATM thanks to a bit of extra zero-carrying in my exchange rate calculation. With this wad of cash in hand, my buddy and I figured we’d look for an old Skoda Favorit to buy and perhaps export. (Naturally.) Better than eating the exchange fee twice, am I right? At a local bar, we asked where we could find a neighborhood with old Skodas in it. After the waiter marked up our tourist map and we followed it for an hour and a half, we arrived at an old school, or Skola. ONE letter off—damn you translation error! On the way back, we stumbled into a book store that had me filling a backpack with old service manuals for Polski/Fiat 125, Moskvich 408, Lada Zhigulis, and various Skodas. Inside of many of the books are large, fold-out cutaways of mechanical and structural components ideal for framing. Right now that project is waiting on wall space. I still ended up carrying about $540 worth of Korunas home.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

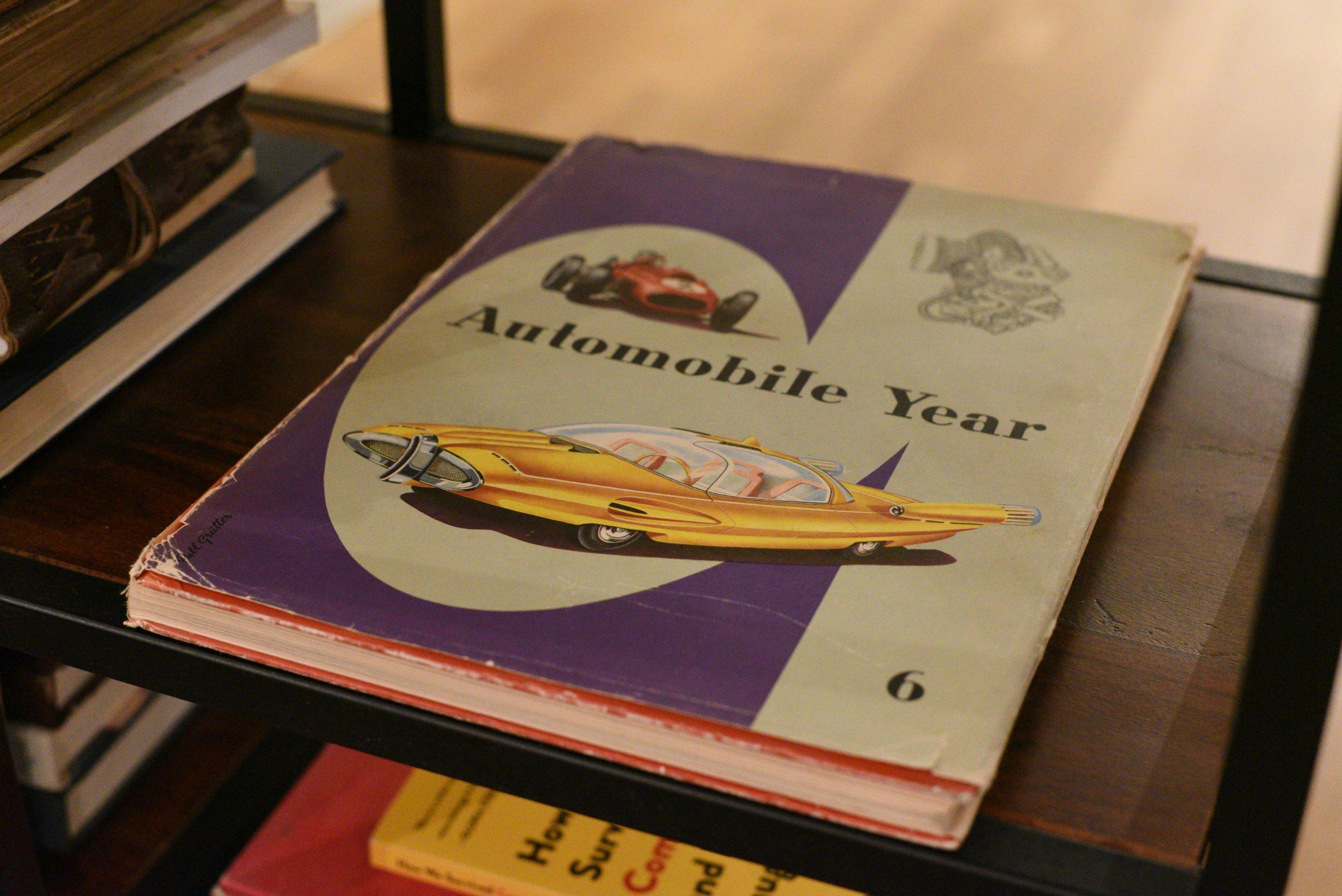

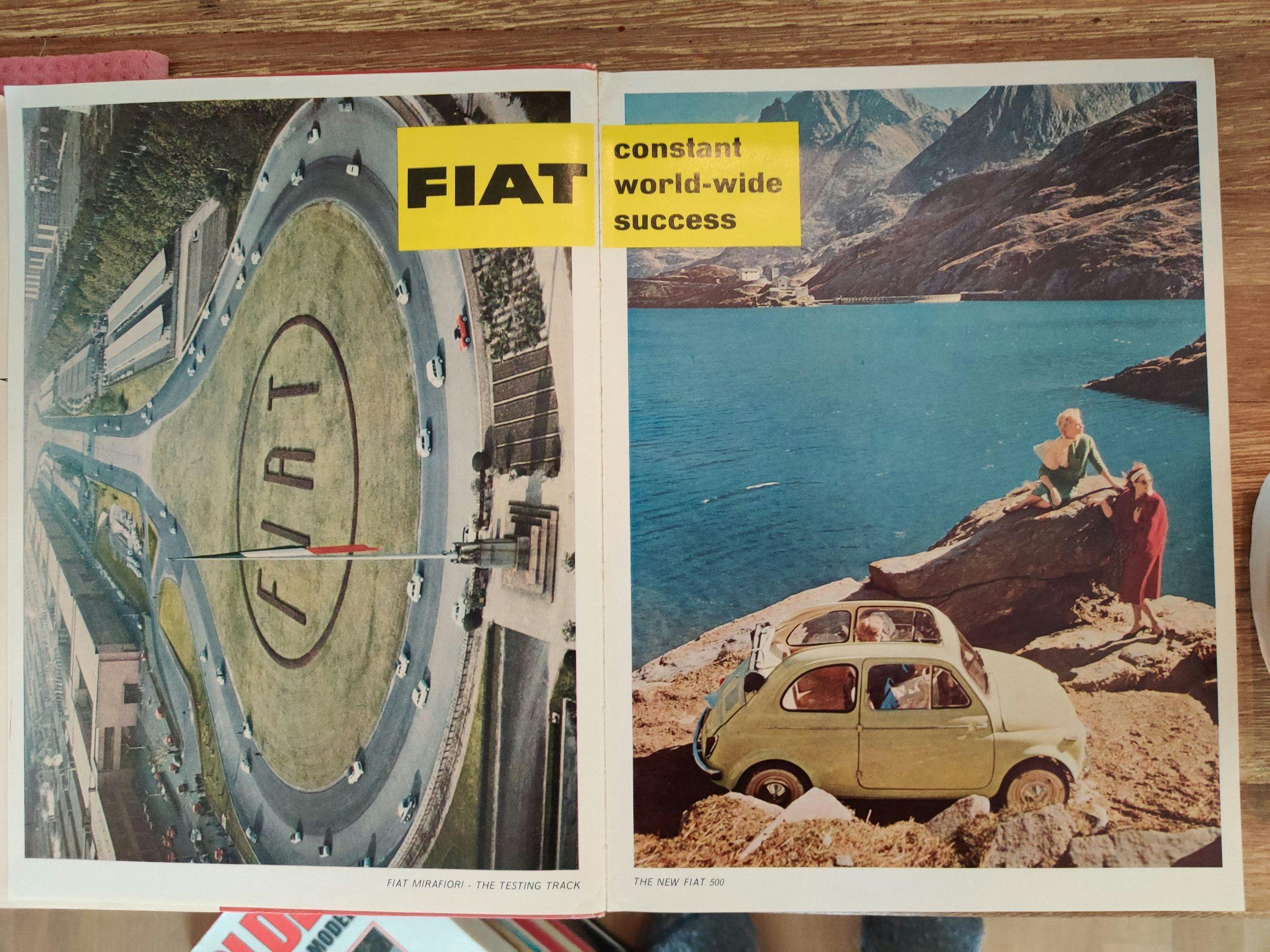

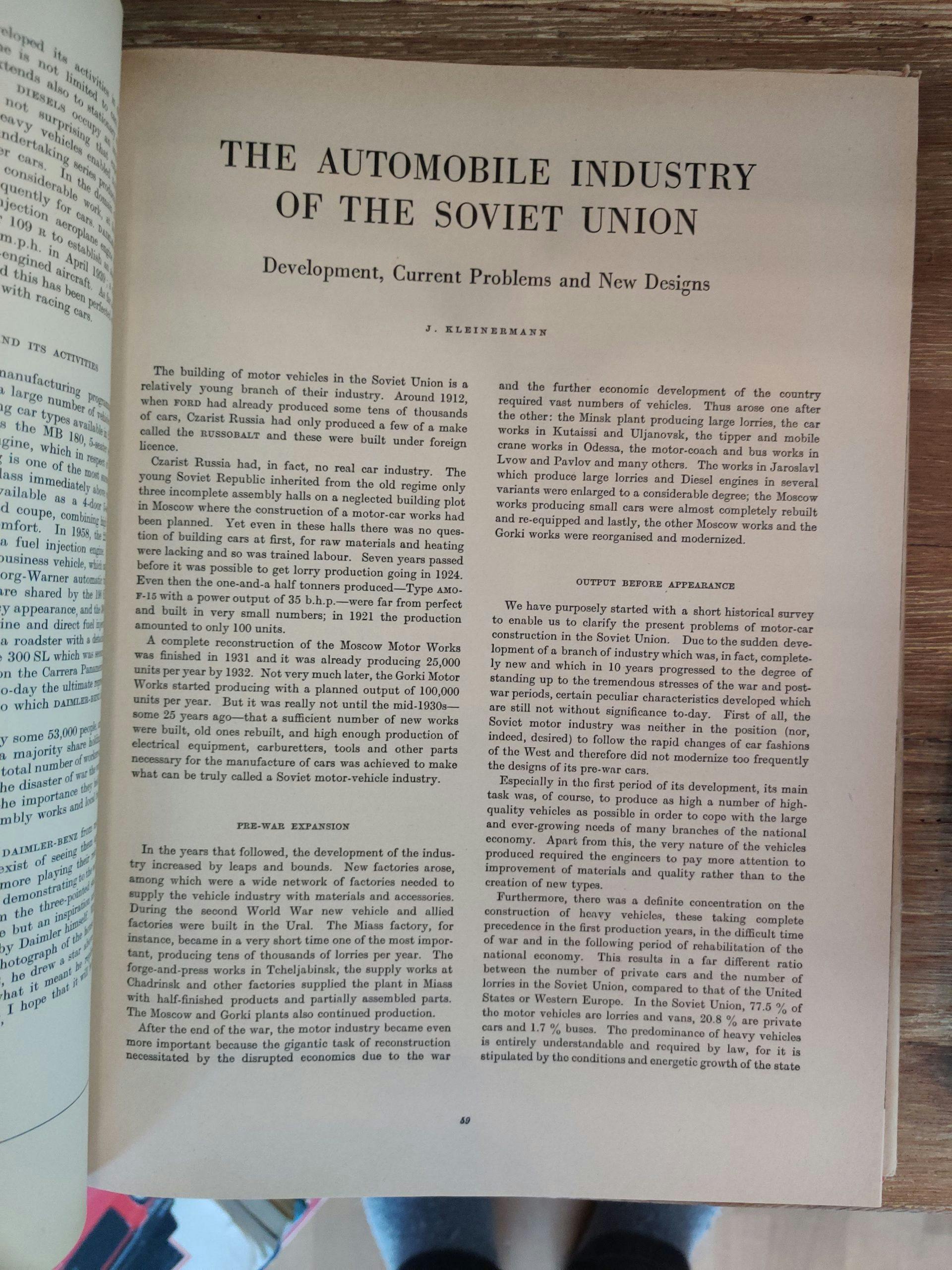

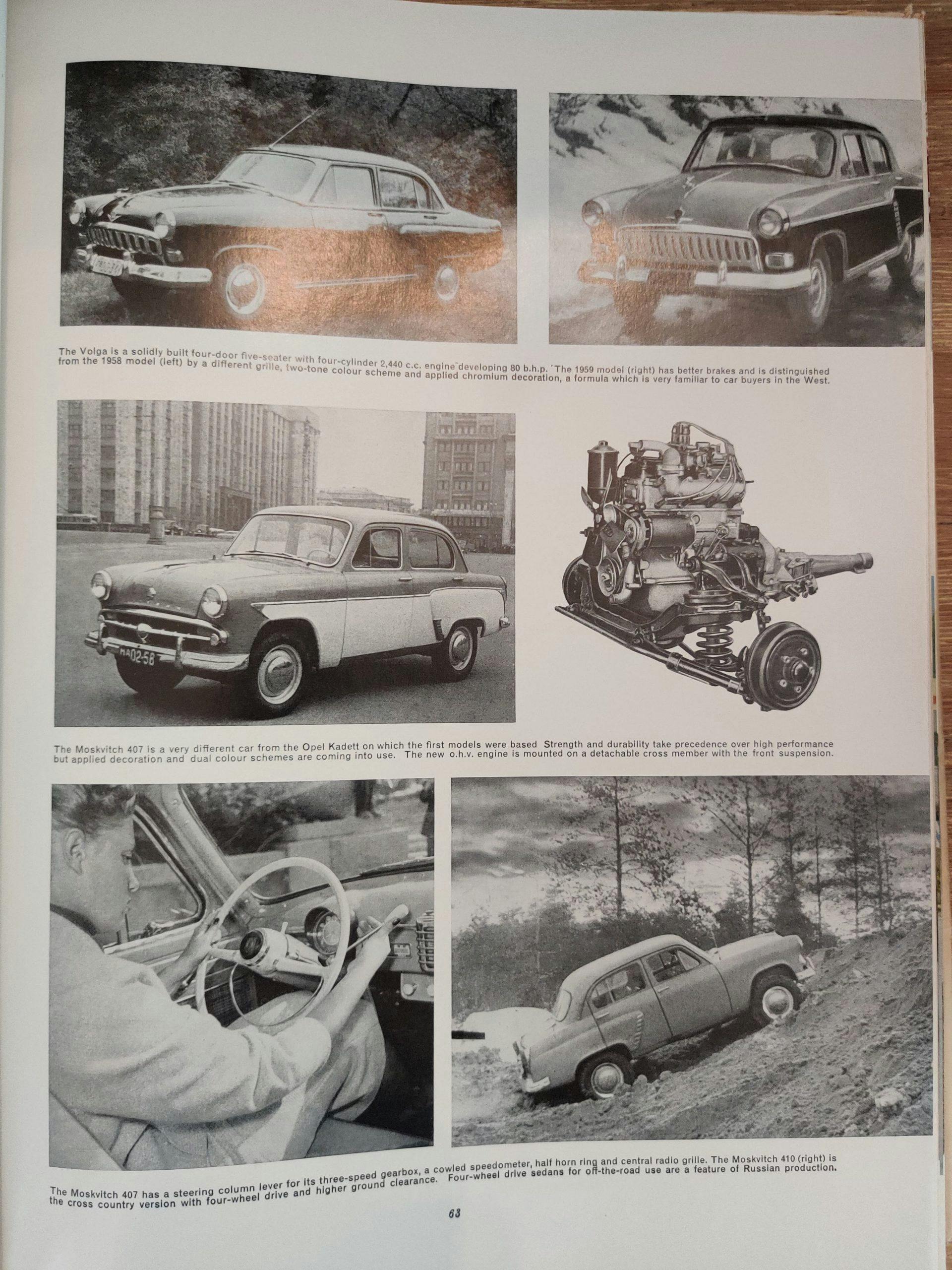

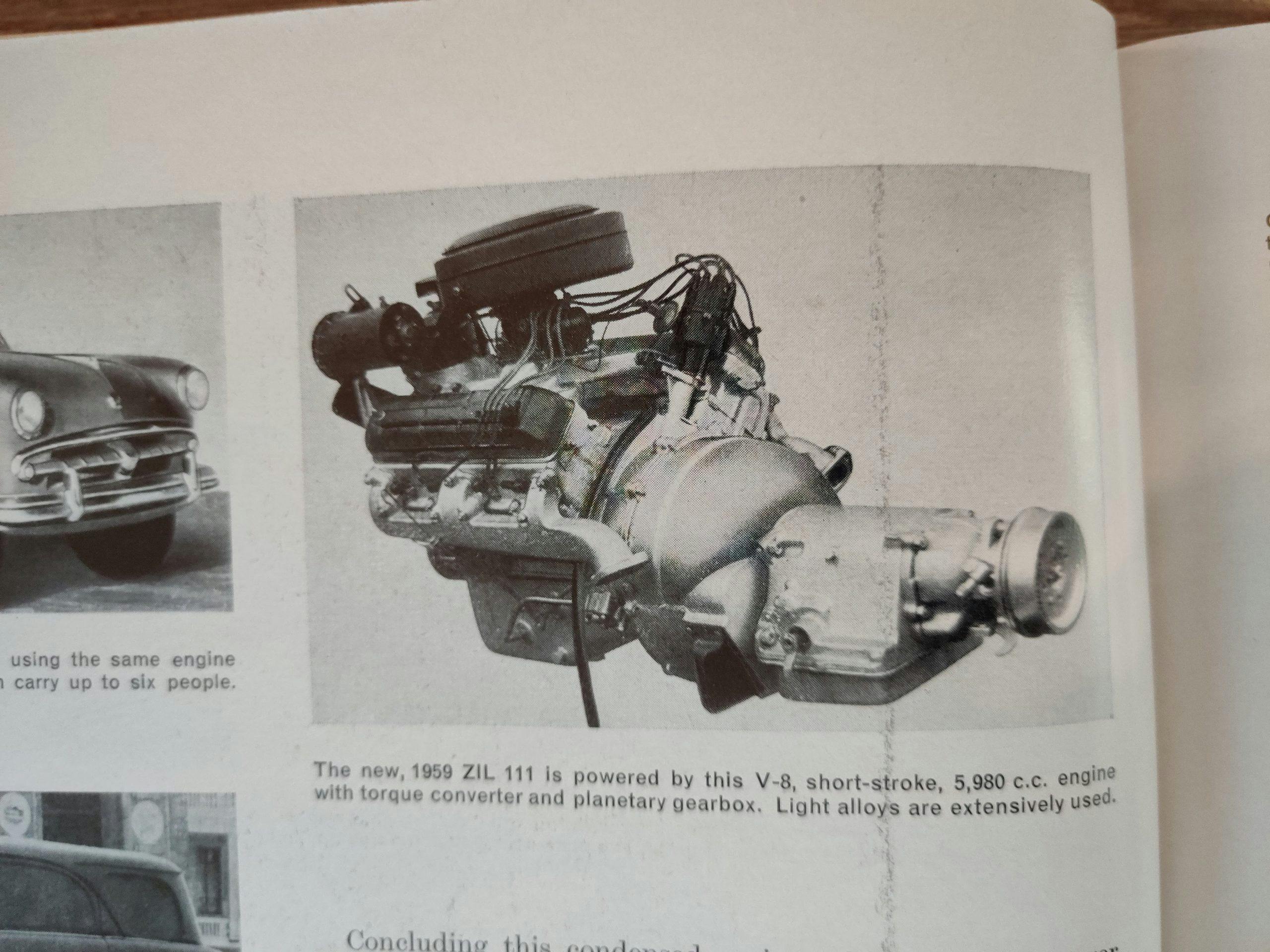

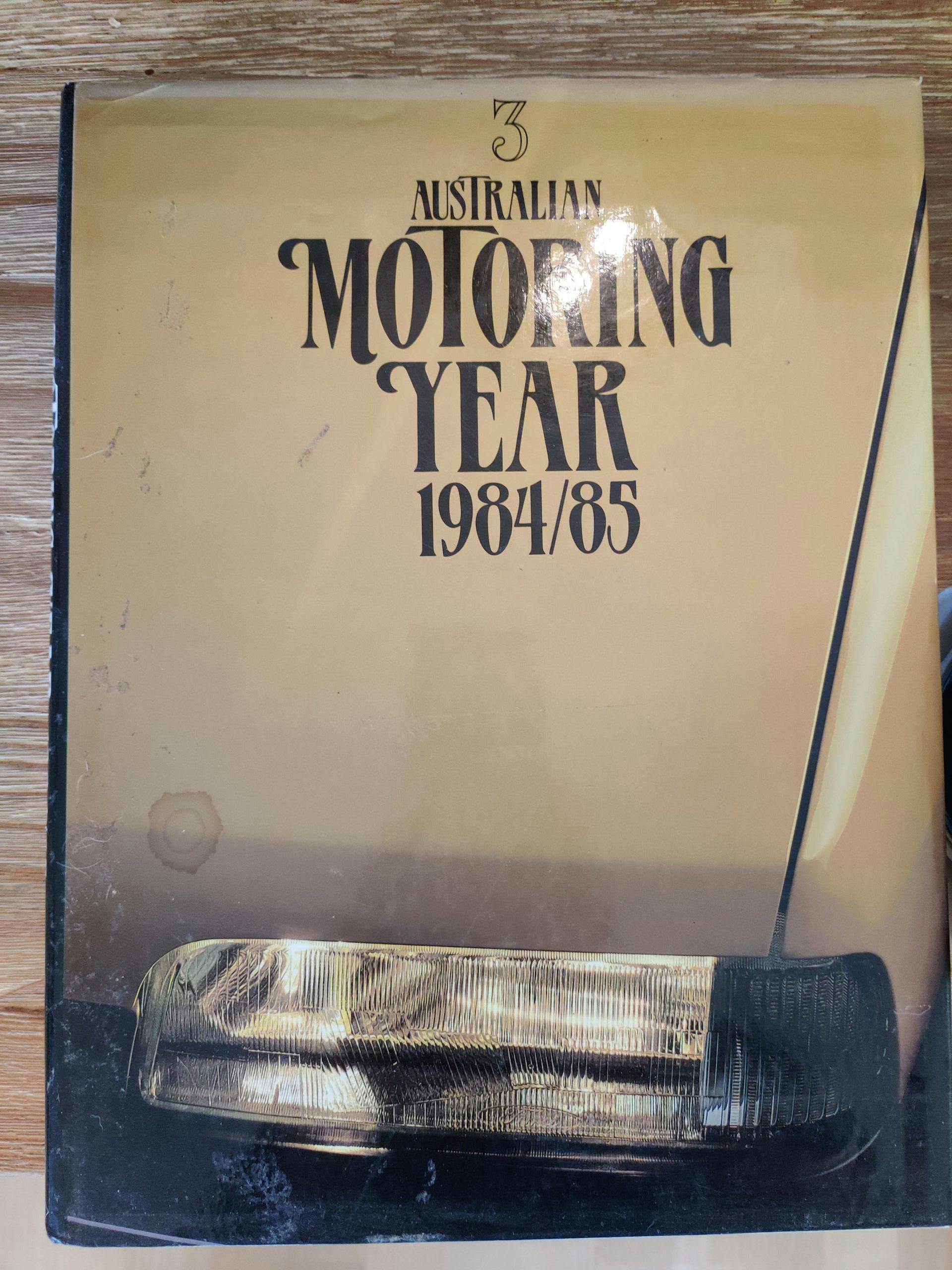

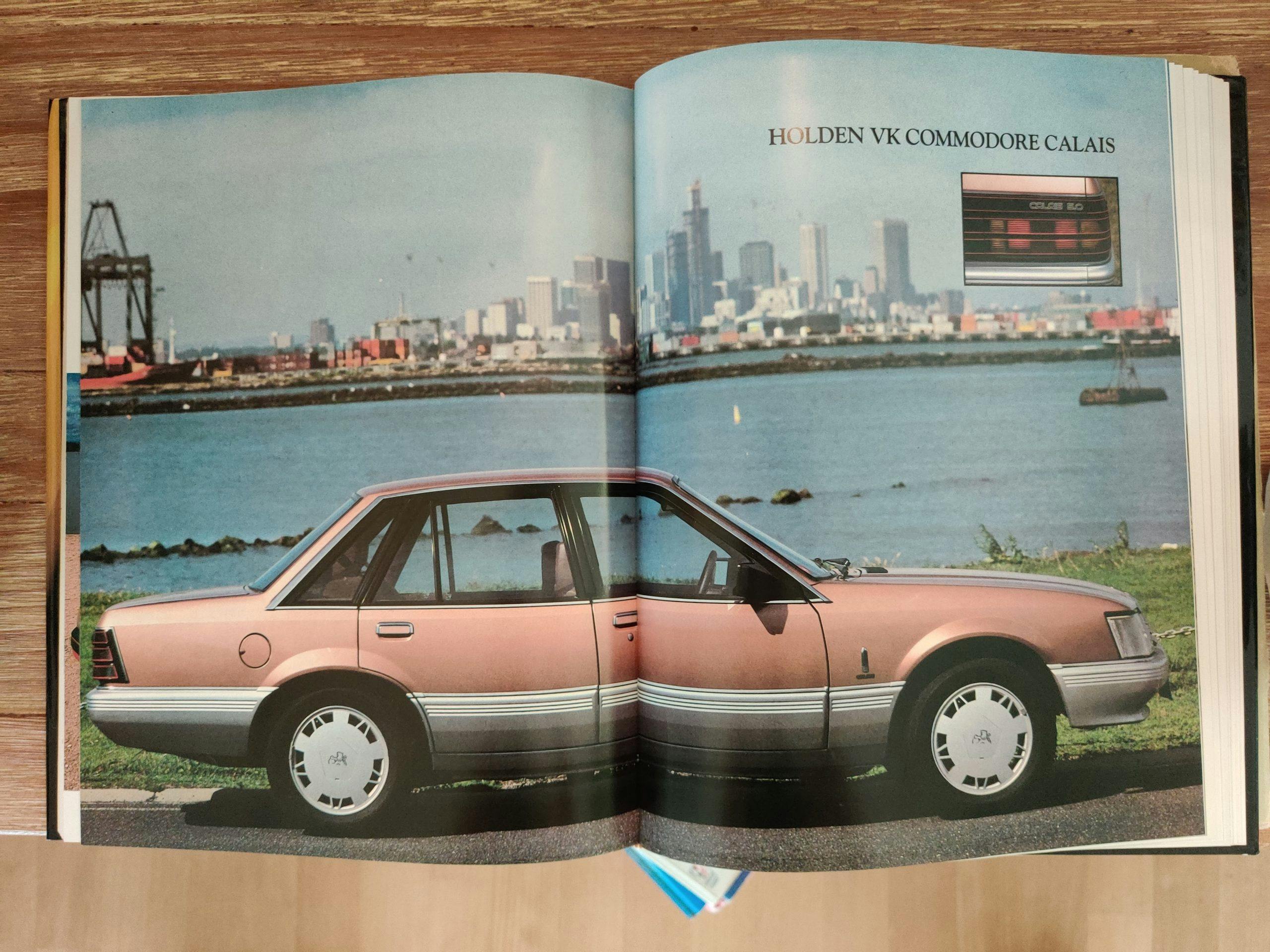

Back to the U.S. book markets. I was at the NASCAR Watkins Glen race and a friend of mine went to the book store of the Glen Motor Museum and I found this gem. After seeing my two most significant automotive market crushes in print, Australian and Russian, I had to move on it. One was a 1984 year-in-review of the Aussie auto industry. As the then-owner of a 1984 Aussie Falcon ute, 1971 Aussie Valiant, and a 1987 Holden Commodore. A few rows down was a 1958 global auto industry review, including an overview of the new all-aluminum Soviet GAZ Volga V8 and the line of 1958 utes (think Aussie El Camino) produced down under. Does it get any better?! Only if you read them with a glass of Finger Lakes wine on an astro-turfed patio at the iconic Glen Motor Inn.

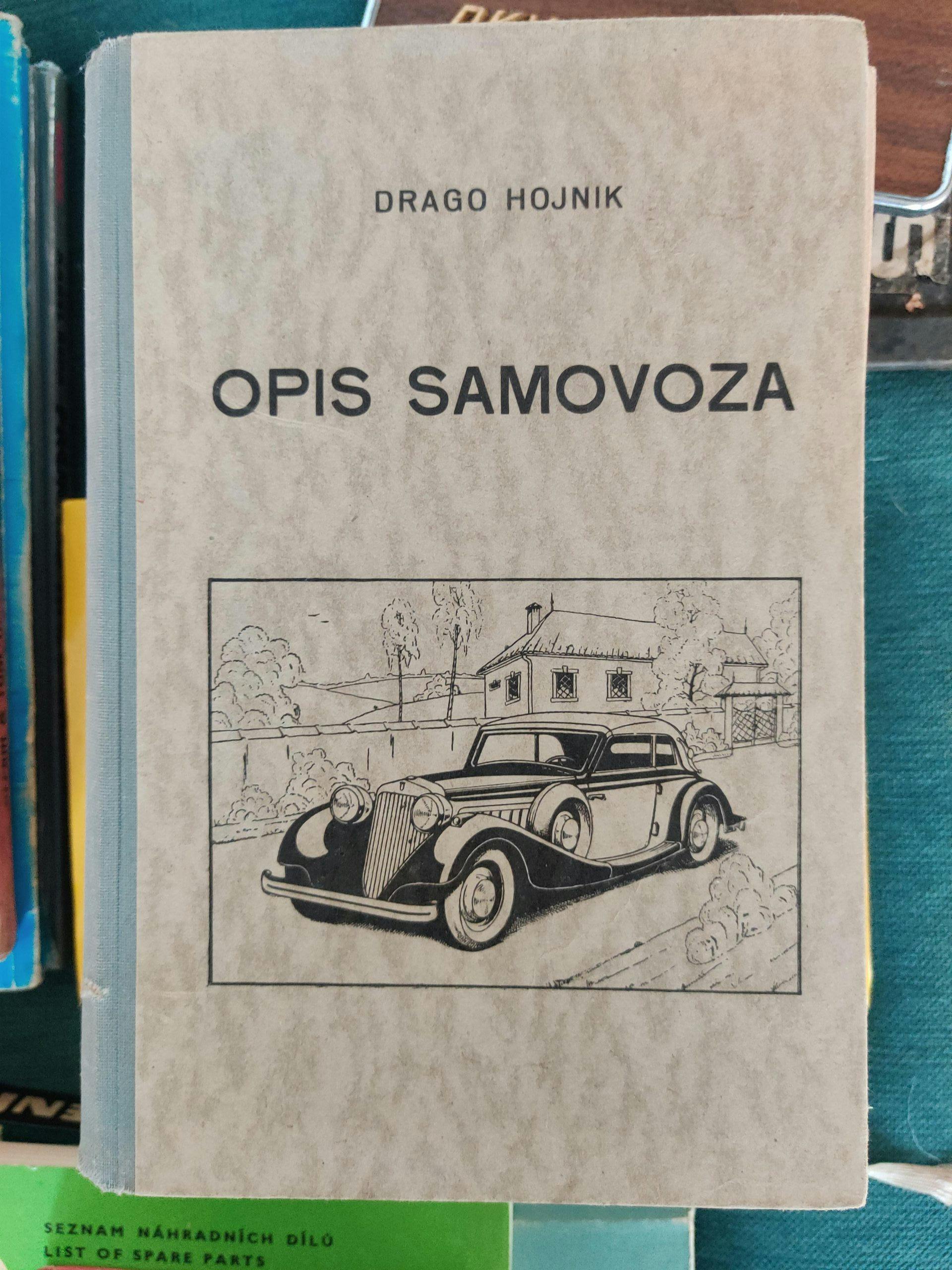

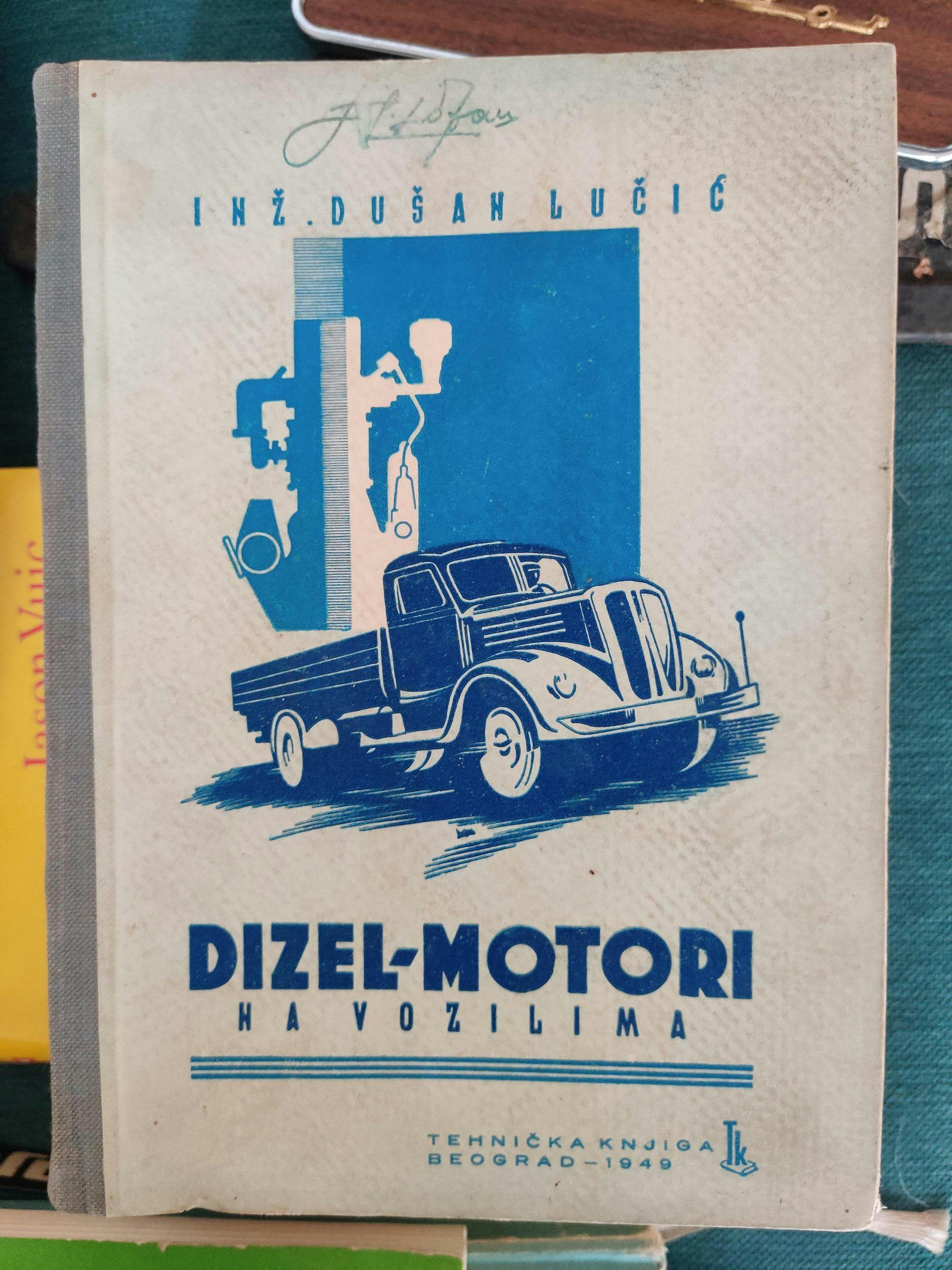

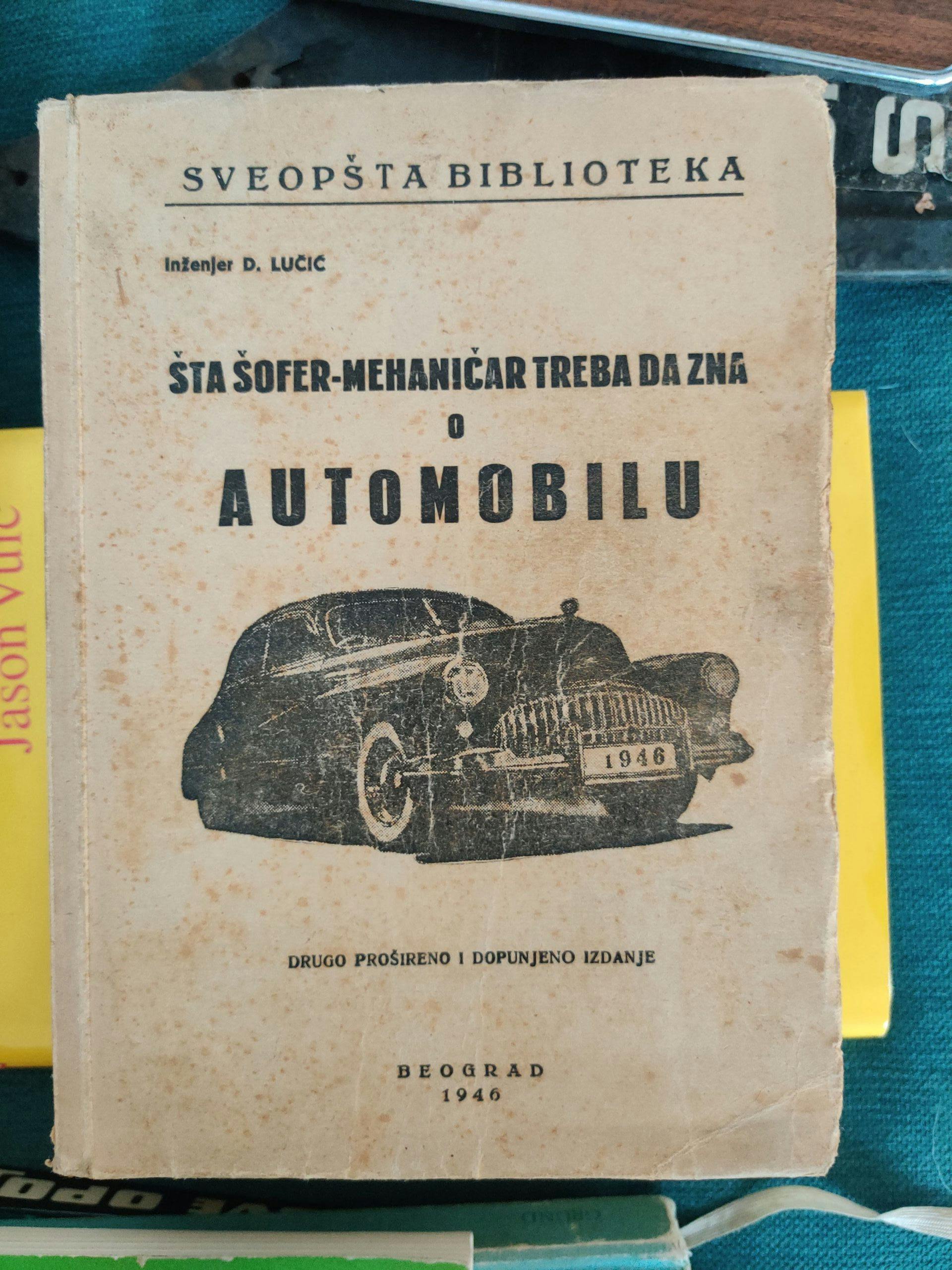

On to Zagreb, Croatia, where the finds get even more bizarre. First off is Opis Samavoza, or “Description of the Self-Propelled Vehicle” in English. Printed in Zagreb in 1944, this book was allegedly banned and few copies exist. Or at least that’s the convincing story the fellow in the book store spun me. Even more curious is the Belgrade, Serbia minted Šta šofer-mehaničar treba da zna o automobilu, or “What a Driver-Mechanic Needs to Know about a Car,” if English is your language. But why on earth is there a brand-new 1946 Buick on the cover?! A little research suggests that Buick was an exhibitor at the Belgrade Auto Show of 1938, so perhaps the efforts continued post-war.

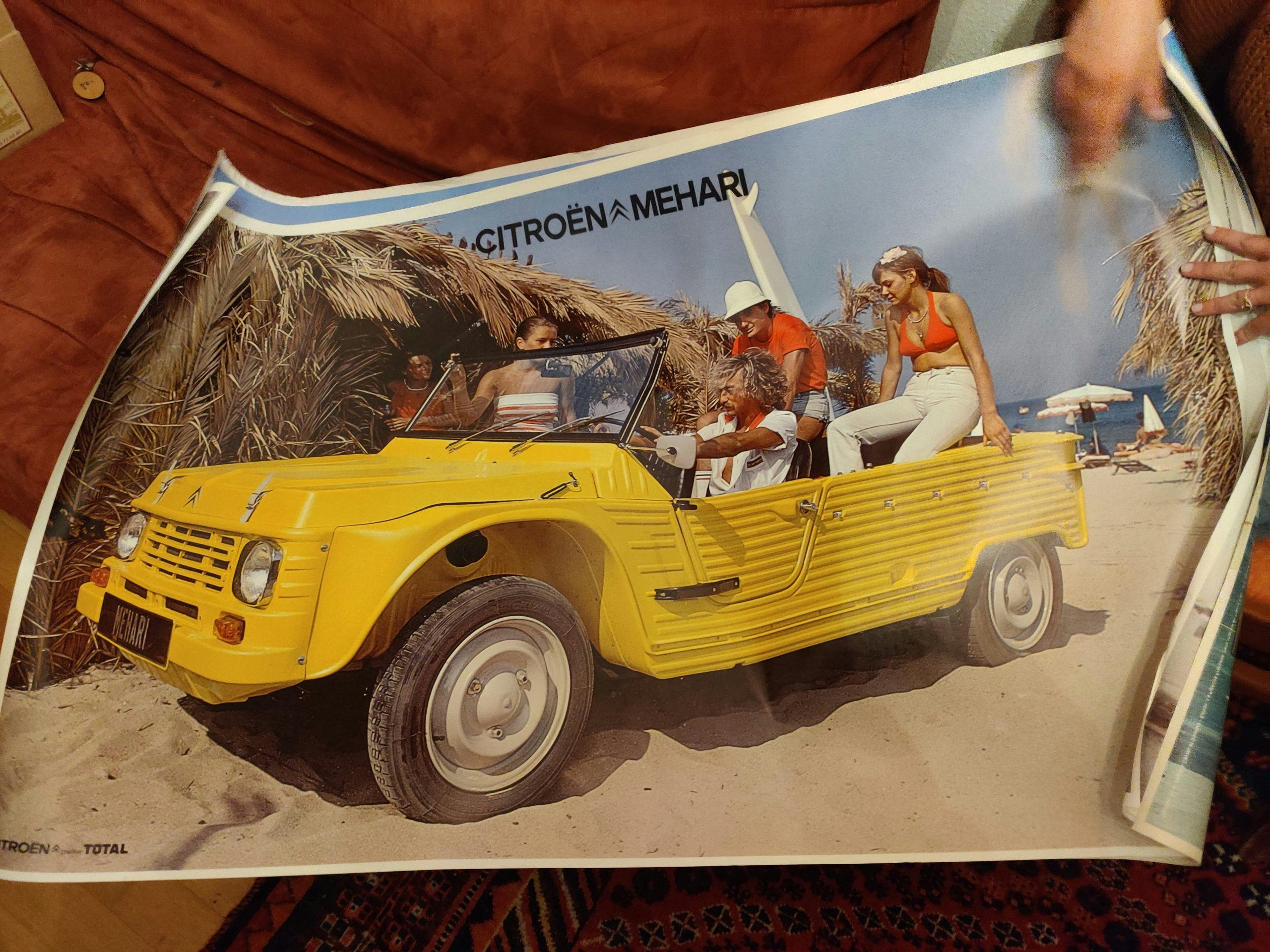

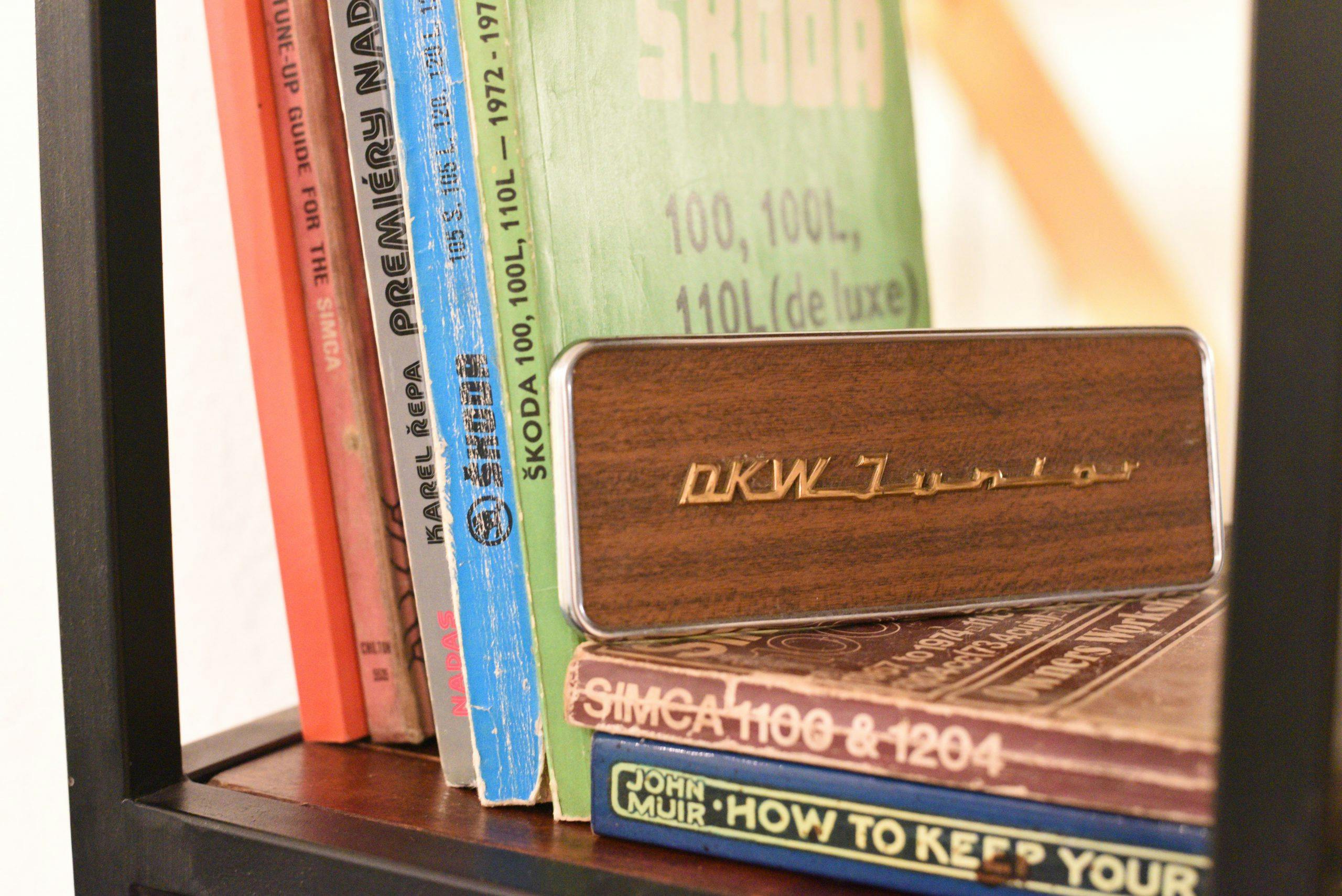

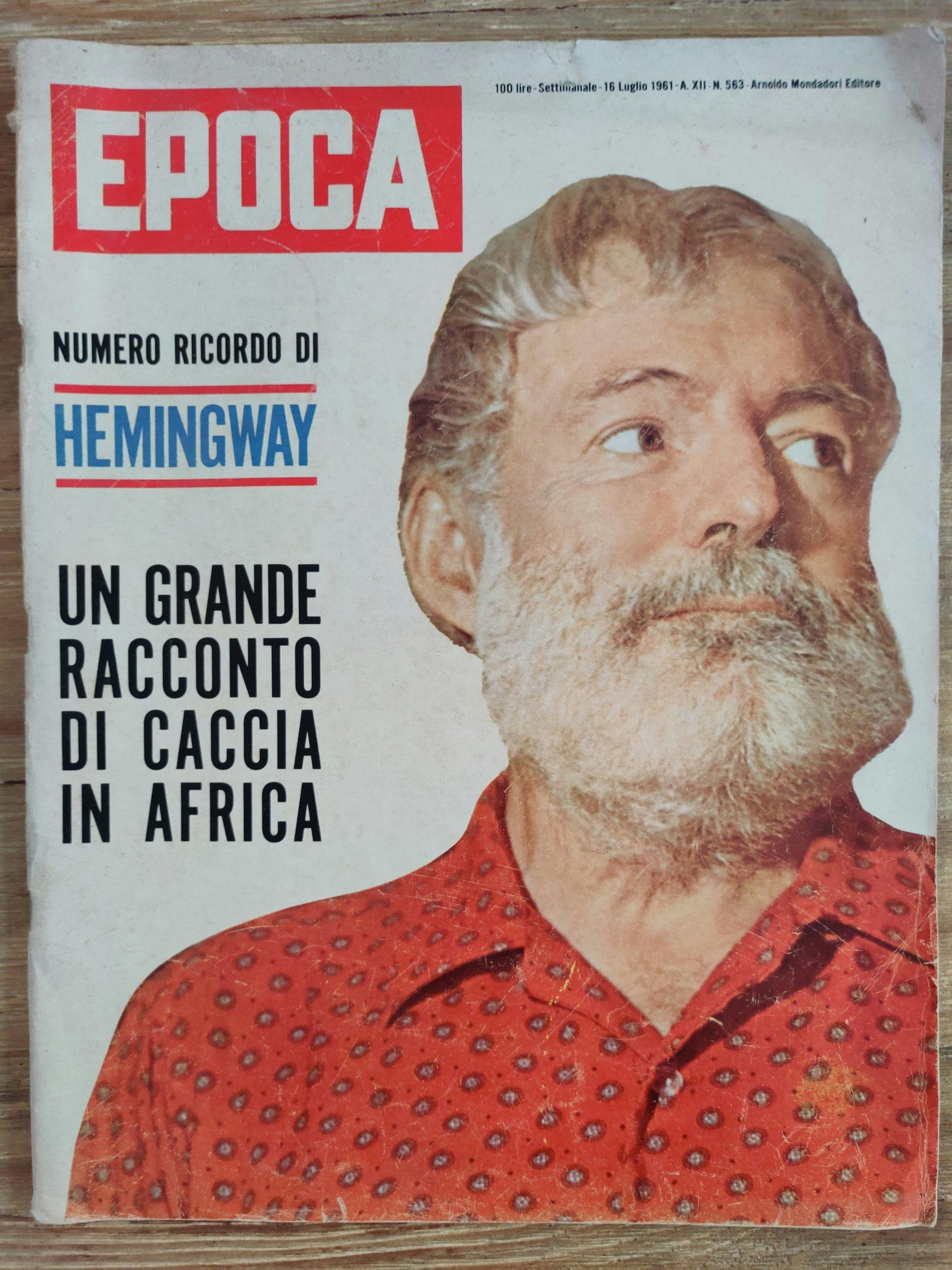

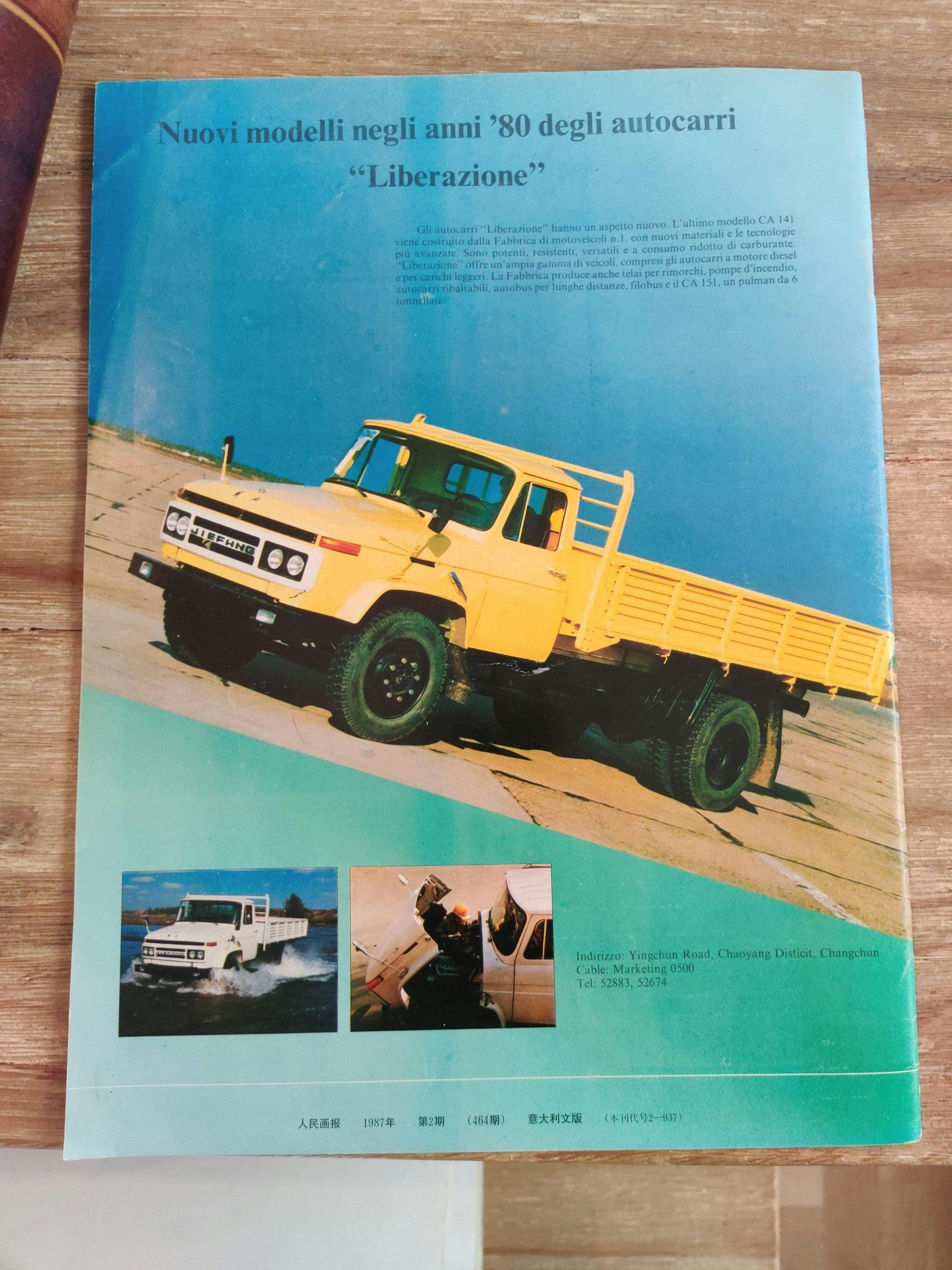

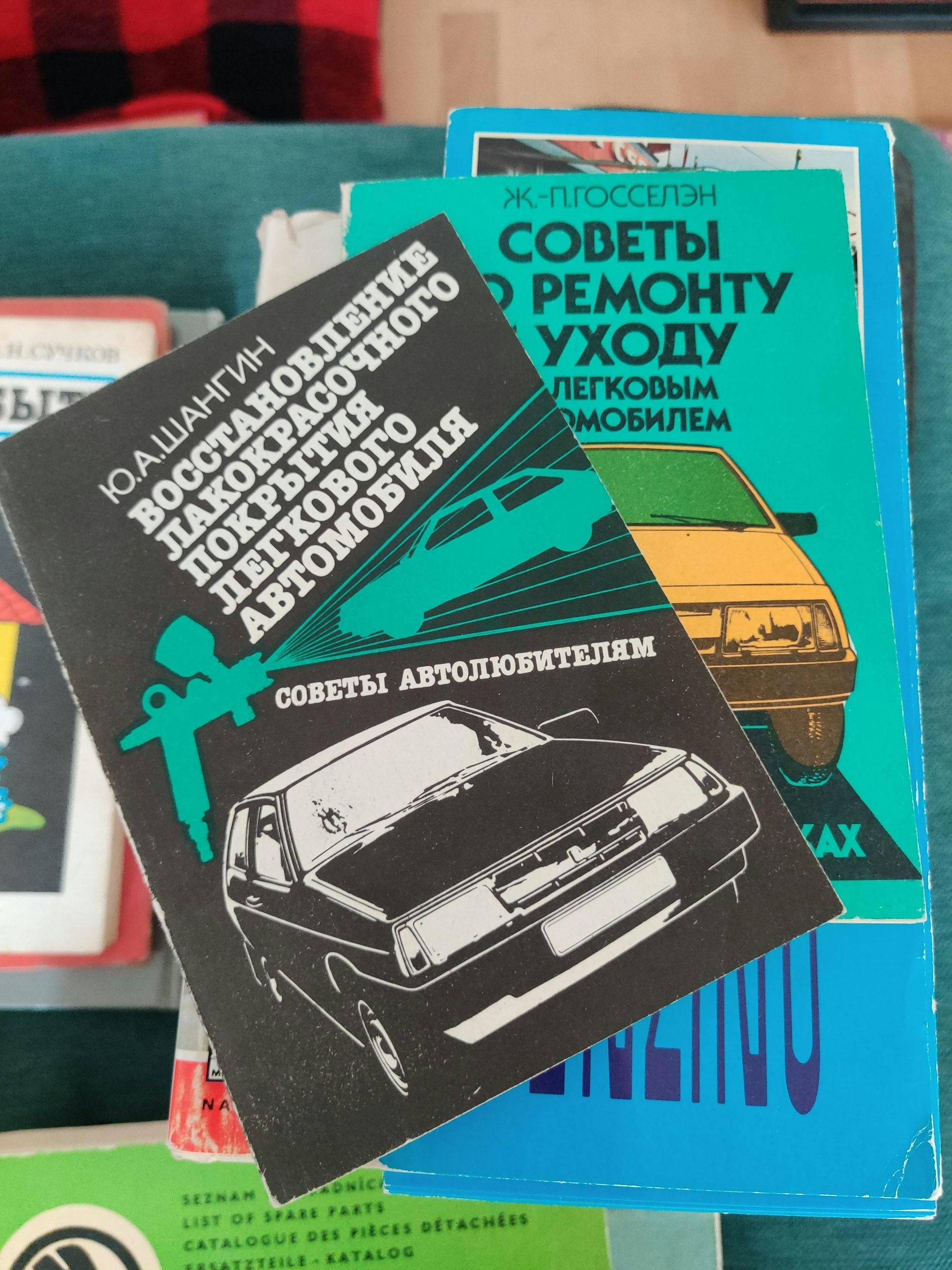

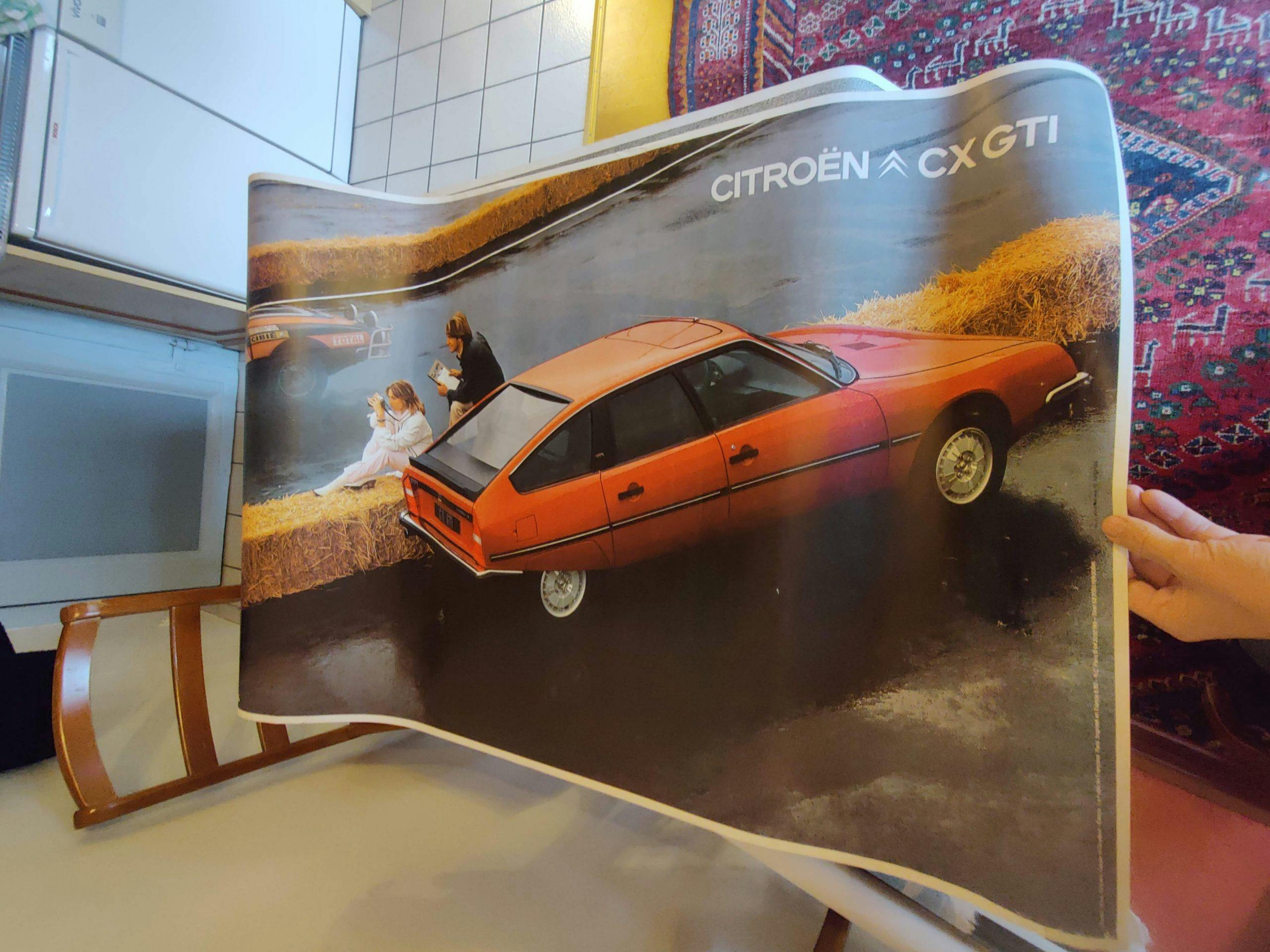

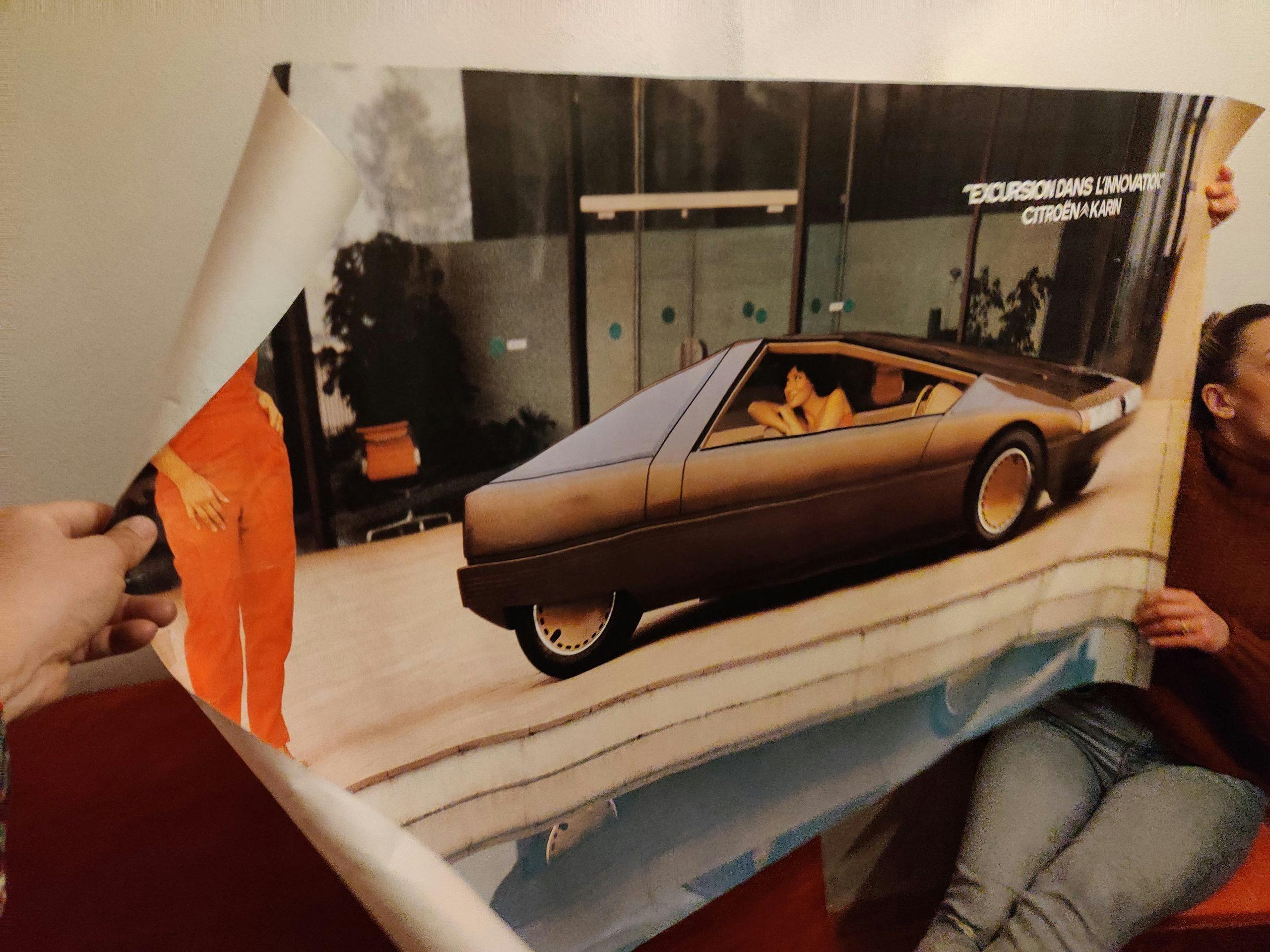

In other areas of obscure automotive media, I also am equally incapable of denying myself. I once asked a hotel if I could buy an Italian magazine out of their display case, because it had an ad for a Chinese truck that wasn’t even available in that market. A Yugo Florida brochure? I’ll gladly give 2 Euros plus 3 more for shipping. Forty-eight full-size Citroën and Porsche dealer posters from the early ’80s that I found in a barn in France? Totally powerless against it. A bunch of Russian how-to books featuring Ladas and Volgas discovered in a pile of car parts in Lithuania? It’s all packing material for my Moskvich roof rack, as far as I’m concerned, and much more of it is in the gallery below. My library will continue to expand—as long as it can be artfully displayed and reduces my overall project car count!