Media | Articles

One man’s scrap is this brilliant metallurgist’s sculpture

Buenos Aires is an overwhelming, vibrant, bustling city of 15 million people where passions run high and classic cars run hot. However, it’s in the Argentinian capital’s Avellaneda barrio that metallurgist and sculptor Mario Tagliavini finds his lust for life, making scale replicas of iconic vehicles in solitude.

Loneliness, he says, is something creatives are uniquely qualified to cope with: “I have ideas in my mind and only I understand how to manifest them.”

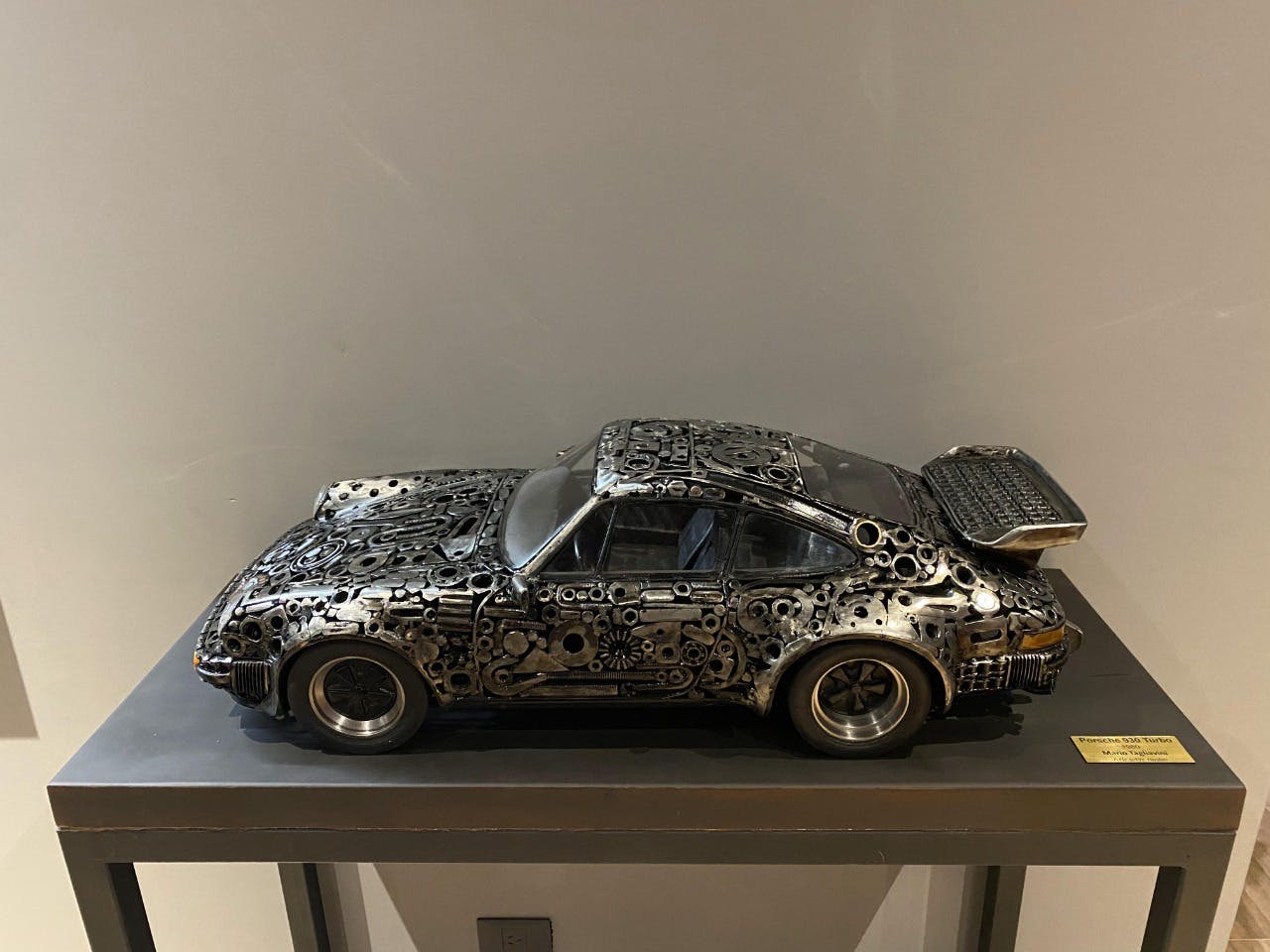

Smooth, but not seamless by design, his sculptures comprise a skin built from commonplace components such as hex nuts, bearings, gears, and piping that were formerly earmarked for scrap. From the Porsche 911 which sports a bicycle chain for its bumper, to the front wing of a Ferrari 250 SWB that’s been shaped out of wrenches, bolts, cogs and screws (some of which have had their heads decapitated from their threads) they are fascinating to visually deconstruct.

“We don’t all see things the same way,” says Tagliavini, who hopes his work awakens people’s imagination to the potential of using unwanted items as art supplies. “I don’t think of things as inanimate objects, I think they have a soul with the possibility for new life.”

Choosing a fifties F1 monoposto [single-seater car] as the subject for his first “basic” sculpture back in 2016, a piece that Tagliavini admits was built with impatient enthusiasm, “I shaped it quickly, but I liked it a lot”, it was dynamic in its presentation with two of its wheels suspended in mid-air. Created without the disciplines of scale or proportion (something which he is now fastidious about) Tagliavini treated it like any usual four-wheeled prototype and put it in front of the public at Autoclasica [an elegance competition in Argentina for classic and vintage cars] to see if it was acceptable to their taste. It sold straight away.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

A year later, his sculptures came to the attention of exhibition organizers responsible for the Buenos Aires International Motor Show, and impressed by his aesthetic, they invited him to display his work. “It was the biggest and most rewarding surprise, I was called to present with some of the best automobile artists from my country at the event of the year. I still can’t believe it.”

Gaining such approval from his peers was a turning point for Tagliavini, “if you’re sure of what you want, you must go and do it”, but keeping a modest view of his own talent is important to the 56-year-old. “All that show of affection for my work is super gratifying, but at events I distance myself from my pieces and just stare at people’s true reactions.”

As a result, his models have become increasingly intricate, ambitious, and sophisticated. “I must see each new job as a challenge that forces me to study form. I try to demand myself with more neat finishes or more realistic details, each one is a new adventure.” To make a Maserati 300 GT’s interior upholstery appear plump, Tagliavini used an airbrush to create the illusion of shadow, and to authenticate his 1:5-scale representation of a Mercedes Benz 280 SE he stamped the iconic three-pointed star emblem on the wheel cups and radiator mask. It’s these touches, he says, that give his pieces a “delicacy” that sets them apart from other automotive and upcycled art.

Other recreations have included a “huge” 1930s Delage D8 120 crafted to a 1:4.5-scale specification, and a Chevrolet El Camino (both of which occupy his living room), as well as items that have gone to private collections such as a 1:5-scale Jaguar E-Type on stainless steel spoked rims, and a beautiful Royal Enfield 350—the only motorcycle Tagliavini has ever sculpted.

During Tagliavini’s childhood, cars were “always part of the landscape.” His father, a mechanic, fettled vehicles back to full health in a small workshop at the back of the family home, “I was almost forced to caress them when going out to play,” but it was his dad’s act of restoring a 1946 Ford Coupé for father-son adventures that left the greatest impression. “I wanted to make my own toys, and used everything that I could to recreate parts of a car. The materials I used had little substance, paper and glue, but when I got older and learnt how to weld, it all changed.”

Dismantling his process, there are two key stages; the first is to research, and the second is to manufacture. “I immerse myself in the web,” explains Tagliavini, who uses photographs, documentation (including original plans if they’re available), as well as diecast models to calculate the dimensions of his pieces and devise accurate, annotated templates.

Next, he bends and sculpts wire rods and mesh to create a three-dimensional frame, “a tedious job,” but a vital one. Get the shape wrong, paying particular attention to the roof, and it could ruin the entire representation. “It is what an observer generally sees at first sight and defines its silhouette to a great extent. So, if I do not get it right, I do not continue until I achieve it.”

To an untrained eye, choosing which consumables to use could be considered even more cumbersome, “it’s a matter that takes a lot of time” imparts Tagliavini, who uses his trusty welding torch to blast them into permanent formation. “I don’t always get scrap according to the size I need so trying to match them in such a way that the least amount of empty space remains can be tricky.” So too, he reveals, is manipulating pieces of 2mm-thick acrylic to take on the shape of a windscreen, set of headlights or windows. Patience, heat and more often than not, an awful lot of revisions are required. Forging, filing and mirror polishing bumpers is also an exercise in traditional, painstaking handmade techniques, but despite the hazards they pose, he is reluctant to wear protective gloves: “It makes me less sensitive to tools and parts.”

Turning wheels out of MDF or plastic is Tagliavini’s current method of production, and although he’s passionate about preserving heritage crafter skills, he’s looking to revolutionize their fabrication with a 3D printer. Their metallic rims, for now, will still be bespoke made using moulds and castings. To finish a sculpture, any sharp or “aggressive” edges are buffed away, but it’s only once a piece has received a client’s approval that Tagliavini will consider a job a job well done. “I get angry, I get happy,” he says. “It’s hard to be someone by my side so I don’t have an assistant, but all these steps, from first to last, I show on my social networks to encourage those who want to dare to be able to do them.”

During a heatwave, when temperatures can hit more than 40°C, Tagliavini’s workshop isn’t the obvious place to make a soothing escape, but it’s “phenomenal!”, he rhapsodies. Sketching, welding, milling and much, much more, it’s a hive of one man’s worth of activity, yet, it’s also a museum of machinery and automobilia. On the walls, there are car parts, road signs, paintings, posters and toys, and on the benches the tools of his trade – from hammers and clamps, to heat guns, lathes, an anvil, a grinder and a computer—promise the stirring inevitability of creation.

Almost apologetically, Tagliavini justifies his interior styling choices—“I spend many hours in there, and it’s hard for me to let go of things, a lot of the scrap I buy ends up decorating my workshop, I just can’t lose these items”,—but there’s something charming about the idea that his hoard of artifacts has grown so great he has to display them on rotation. “I have been collecting for years, I had an antiques business and bought more than what I sold.”

Despite imposing his own social distancing measures, Tagliavini is soothed by the company of low-level music, “it helps me to relax and concentrate, silence creates an emptiness in me that I don’t like”, and he’s always glad of a second pair of hands when the time comes to part ways with a piece: “yes, they are heavy, sometimes up to 50kg.” It’s a natural and gratifying step, but “letting go” of a car sculpture, which will have been his sole creative focus for months, can be a deeply moving matter. “I feel a very strong connection with them,” says Tagliavini. “And I’m not ashamed to say it, but with some, I feel I shed a tear.”