Media | Articles

Model Citizen: For 40 years, Luca Tameo has realized F1 in miniature

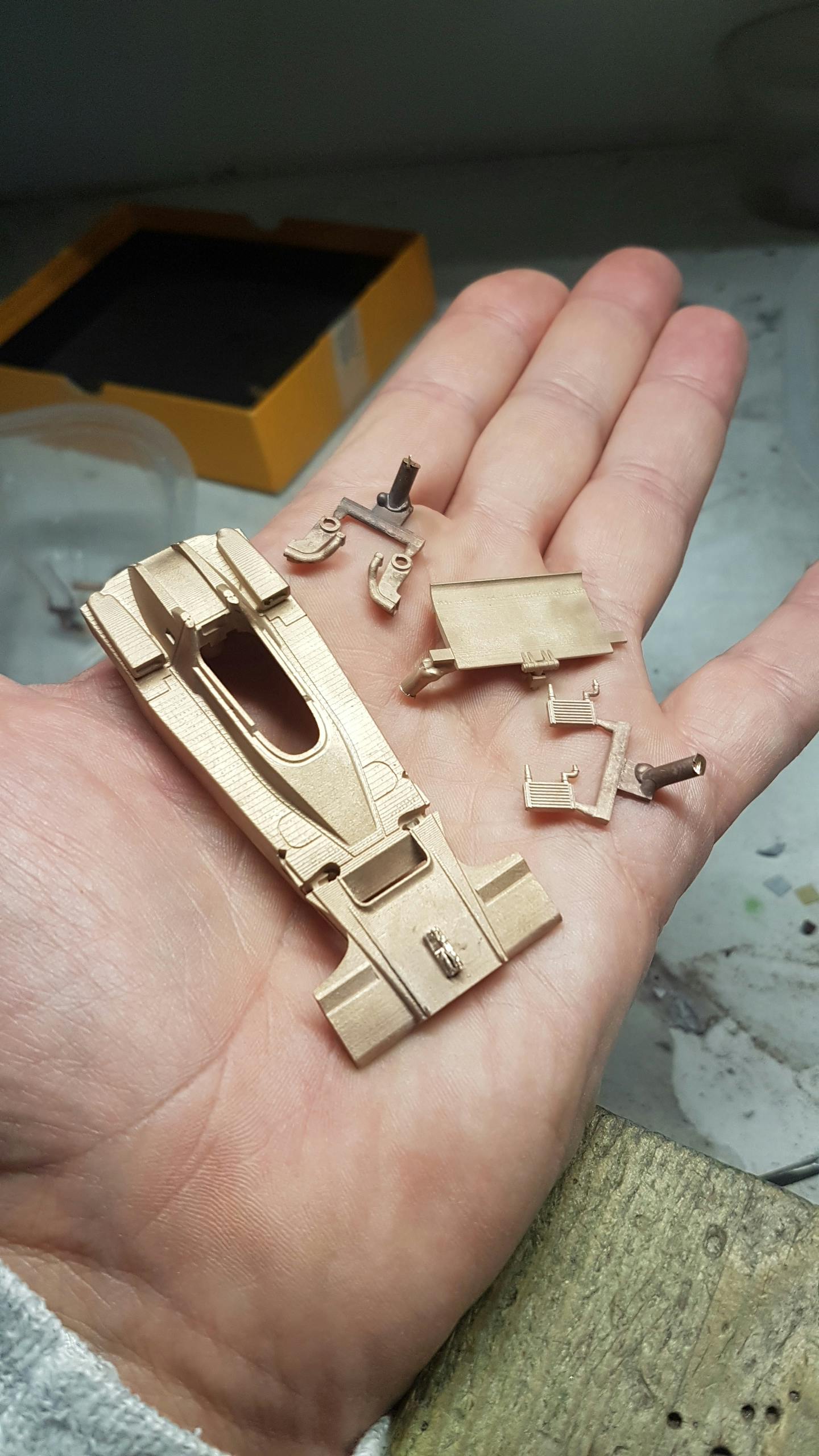

The steering wheel of Ayrton Senna’s 1988 World Championship-winning McLaren MP4/4 Formula 1 car was about 10 inches across. Now imagine that same steering wheel rendered as just one tiny, 0.2-inch part among 300 parts in a scale model kit of his McLaren that, when completed, is no more than four inches long. Believe it or not, there are people who build these for fun.

Most of us assembled a plastic car model (or three) as kids. That every town had a hobby shop and the aroma of Testors paints filled the basement seems today like a quaint amusement from the distant past. However, for a small but loyal group of hard-core hobbyists who are more like jewelers or watchmakers than modelers, car modeling remains a serious business borne of a rabid obsession for miniaturized realism.

For more than 40 years, one small Italian boutique, Tameo Kits, has fed the hobbyist’s habit with an extensive menagerie of metal kits, surviving against market changes and social forces that has thinned the ranks of modelers and model companies.

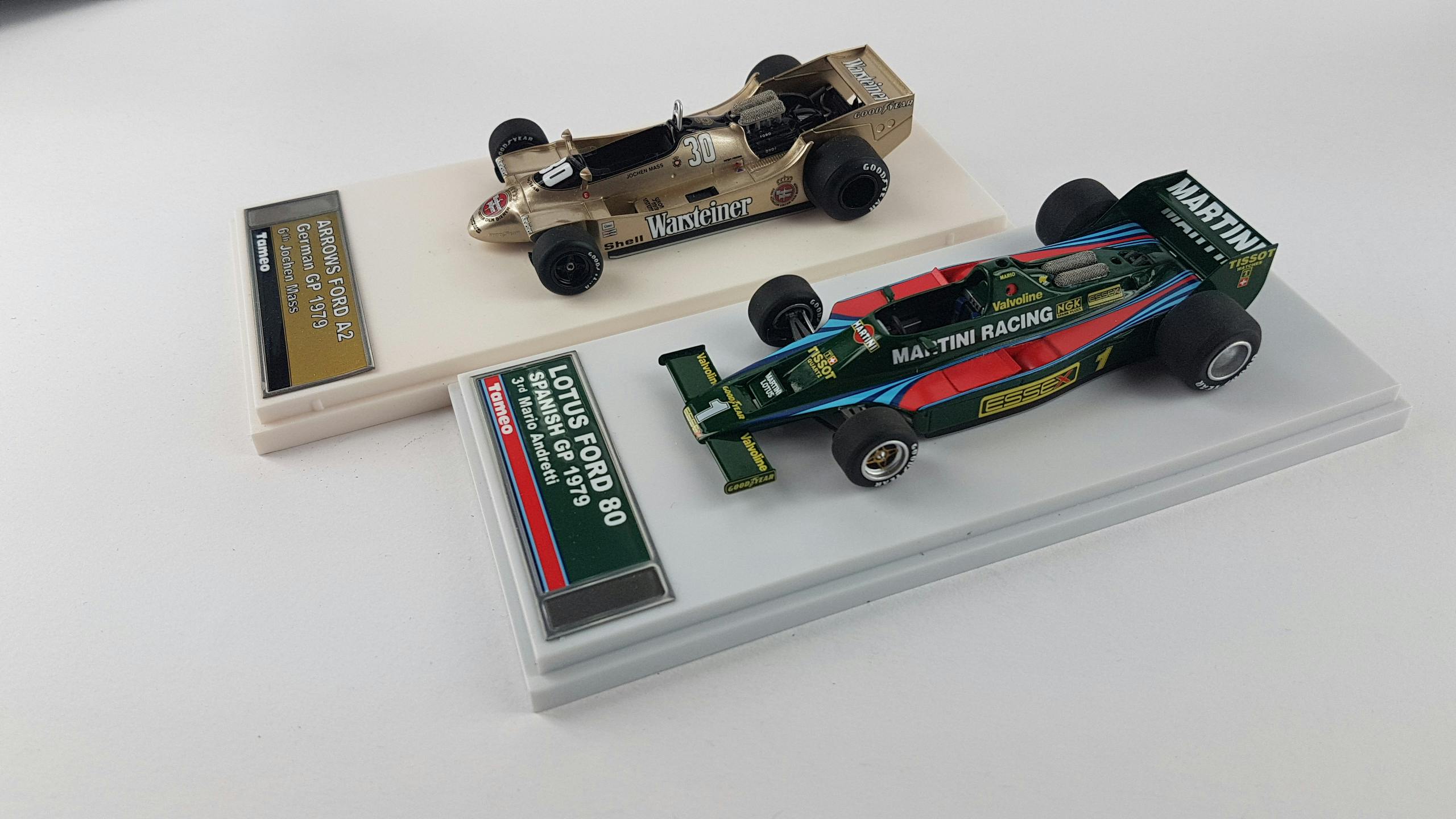

A peruse through Tameo’s catalog (available at the company website, tameokits.com), which the company playfully dubs “Turtle Soup,” is a stroll through some of the highlights of Formula 1 and sports car racing. Everything from the forgotten AGS Cosworth JH23 from the 1988 Monaco Grand Prix to Jody Scheckter’s 1976 six-wheeled Tyrell P34, to Alberto Ascari’s Ferrari 375 from the 1952 Indianapolis 500 are rendered in 1/43-scale kits that sell for $50 to $125 depending on the level of detail.

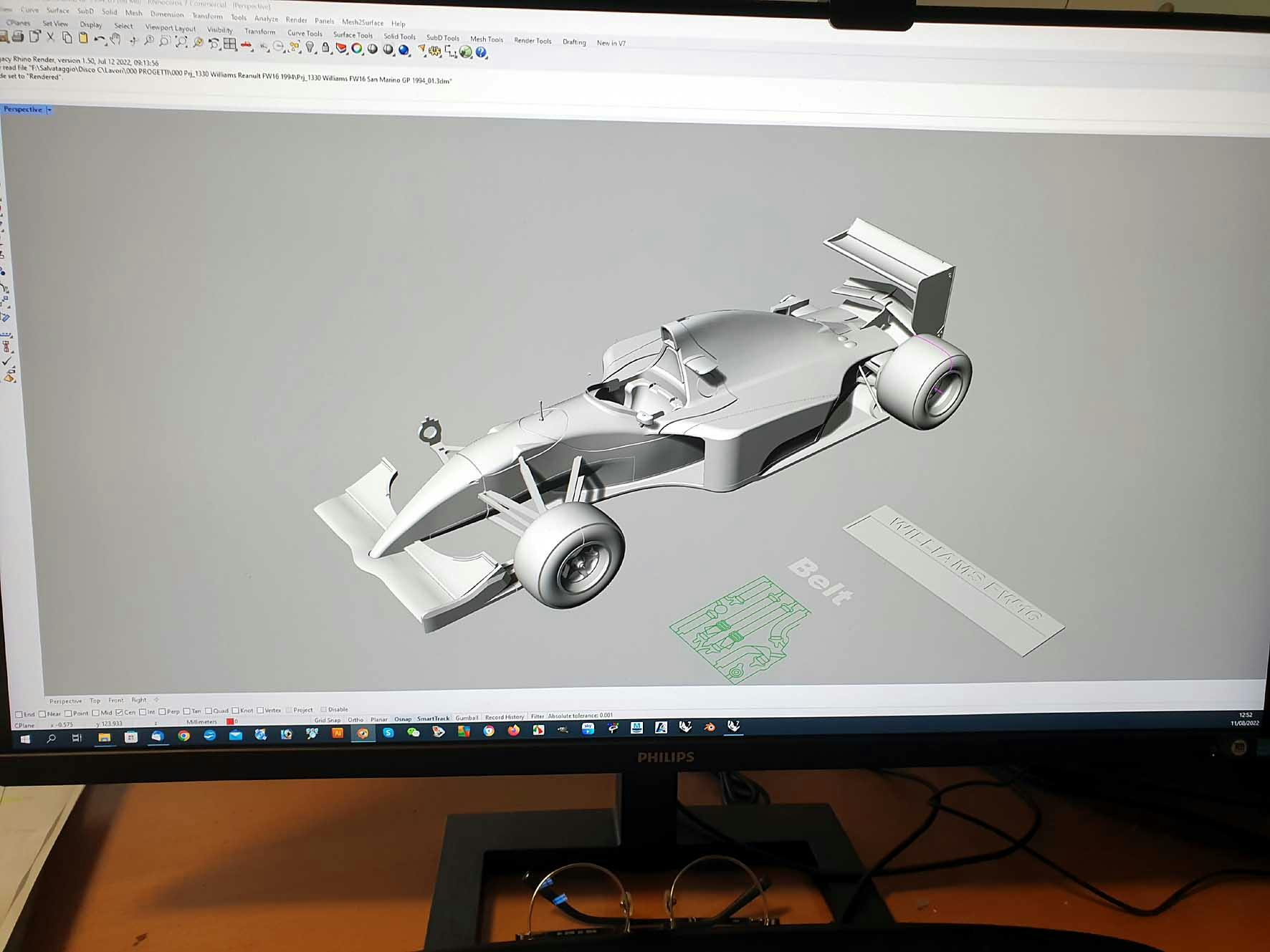

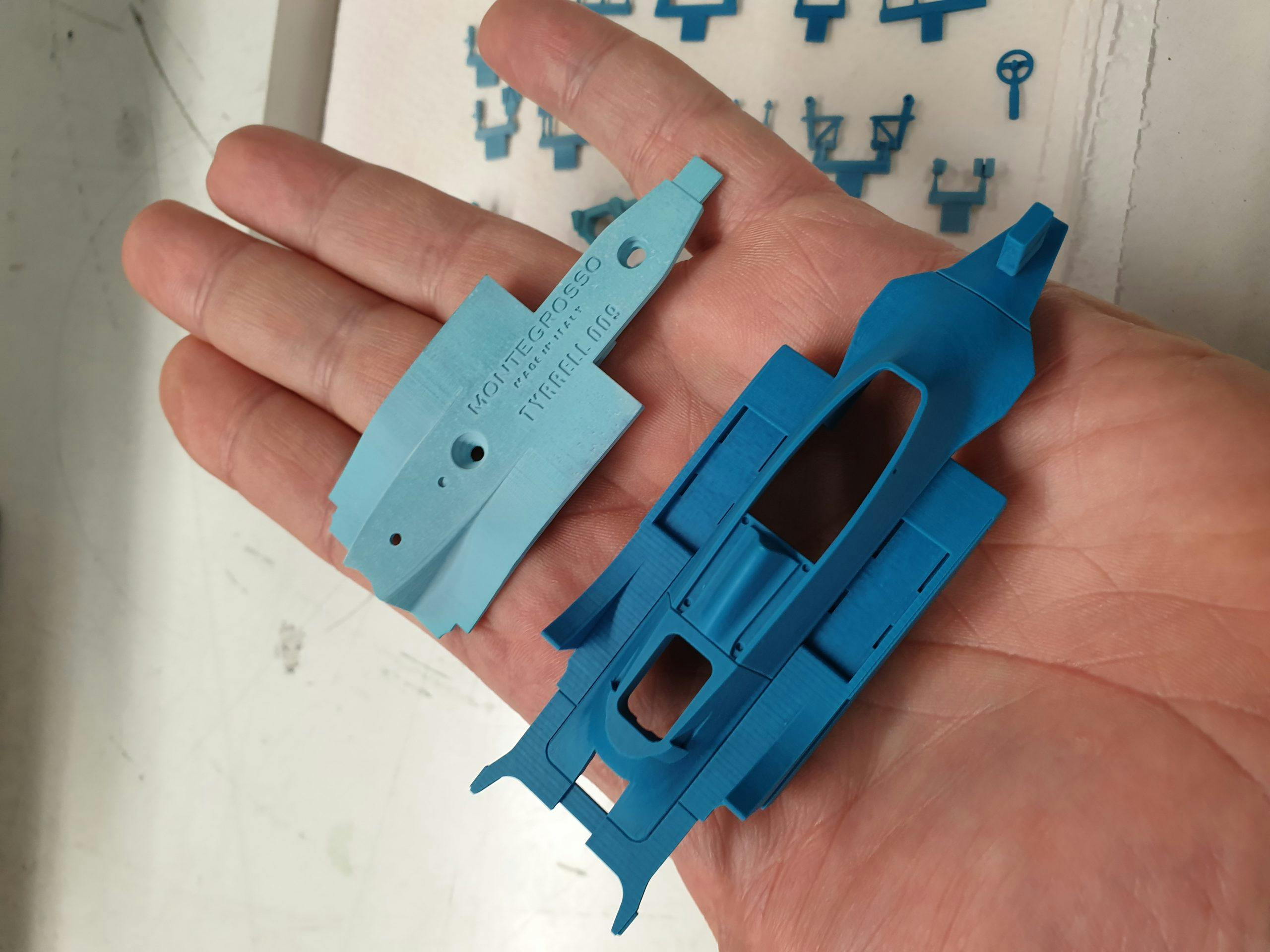

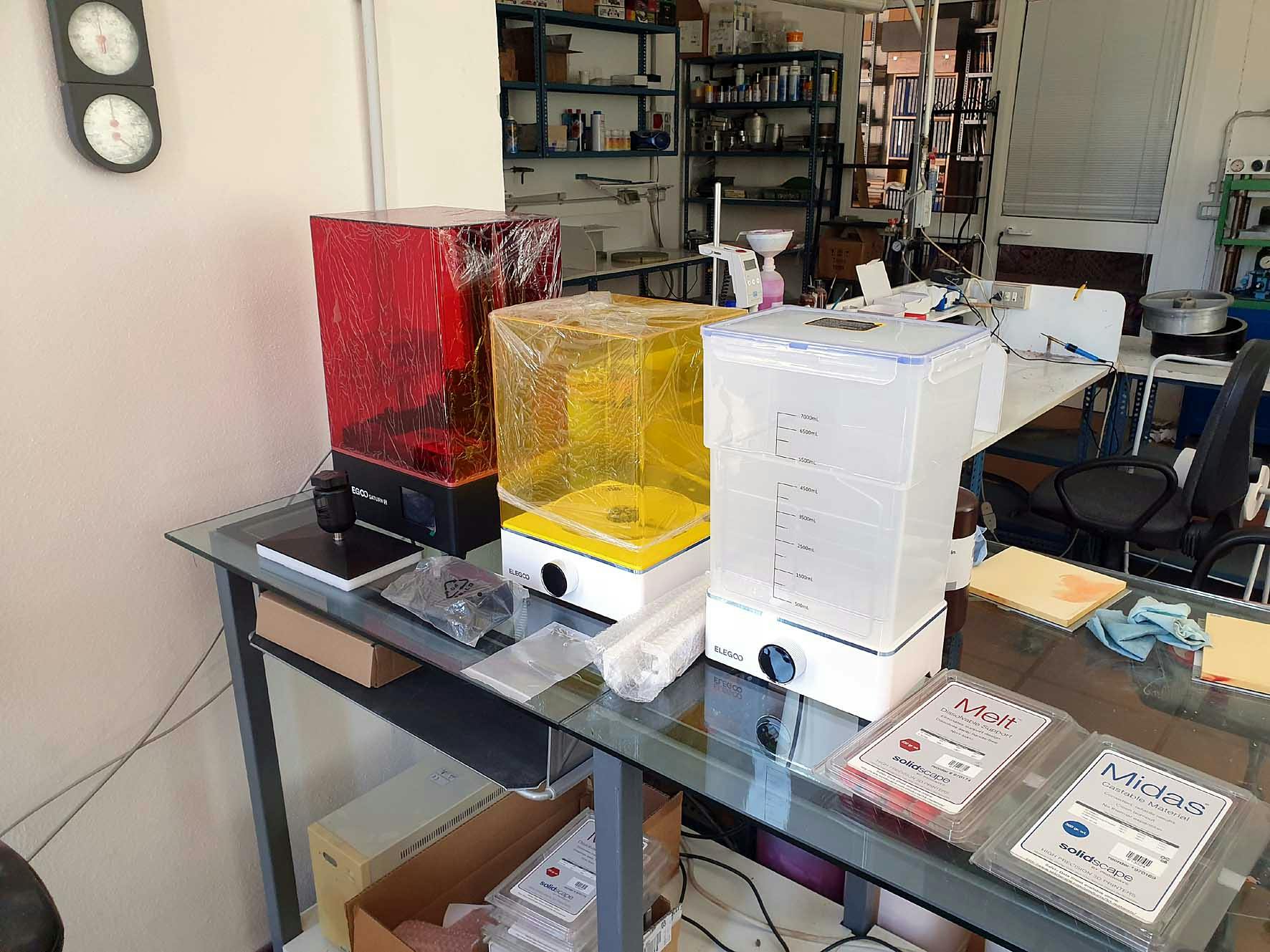

The kits are produced using a combination of old-world metal-casting techniques, modern photoetching, and 3-D printing, and they are shipped around the world in individual 3 x 5-inch cardboard boxes. “Since 1981 we have produced over 700 models that are always in the catalog and constantly in production,” says the company’s founder, Luca Tameo. “I think that Tameo Kits is the only company in the world that has kept the entire production in range without ever running out of a single reference.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

For modelers who work in the fiddly 1/43 scale, a relic of early 20th century model railroading that was later embraced by popular British toymakers such as Corgi and Dinky, the Tameo name is a gold standard. That’s partly because of the kit quality, partly because of the sometimes-obscure subjects that are not offered as models by any other company, and partly because of the Tameo’s longevity.

“Tameo is a survivor of the classic European model car companies,” says David Barnblatt, a model builder and Tameo distributor through his Venice, California-based company, Vintage 43. “During the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, there was a vibrant industry of 1/43rd artisan model car makers in Italy, Germany, France, and the U.K.. There were also a few in the US and Japan. Nearly all of the companies have vanished due to competition from diecasts and the readily available plastic model kits that are larger at around 1/24th scale. But Tameo stuck around because they specialized in Formula 1 models and they were also technically a few notches better than the rest in precision quality and ease of assembly.”

Tameo, who is now a very youthful 60, started the business out of his house when he was 16, building models on commission after his father, a manager at Fiat, bought him his first kit, a model of a Lancia Stratos rally car. He sold the finished model and used the money to buy two more kits, selling those as well. A lifelong fan of Formula 1, Tameo “felt the need to make something that was entirely mine,” and produced his first model from scratch, a 1978 Arrows Ford A1 which was an obscure gold-and-black F1 car sponsored by the German beer company, Warsteiner.

He subsequently met and befriended Andre-Marie Ruf, a French pioneer of small-scale metal car modeling who produced what are now highly collectible kits bearing his initials, AMR. Ruf taught Tameo the art of sculpting parts in wax as part of the prototyping phase of kit design, and in 1983 Tameo designed his first kit in 1/43 scale, Nelson Piquet’s 1983 Brabham BT53 F1 car.

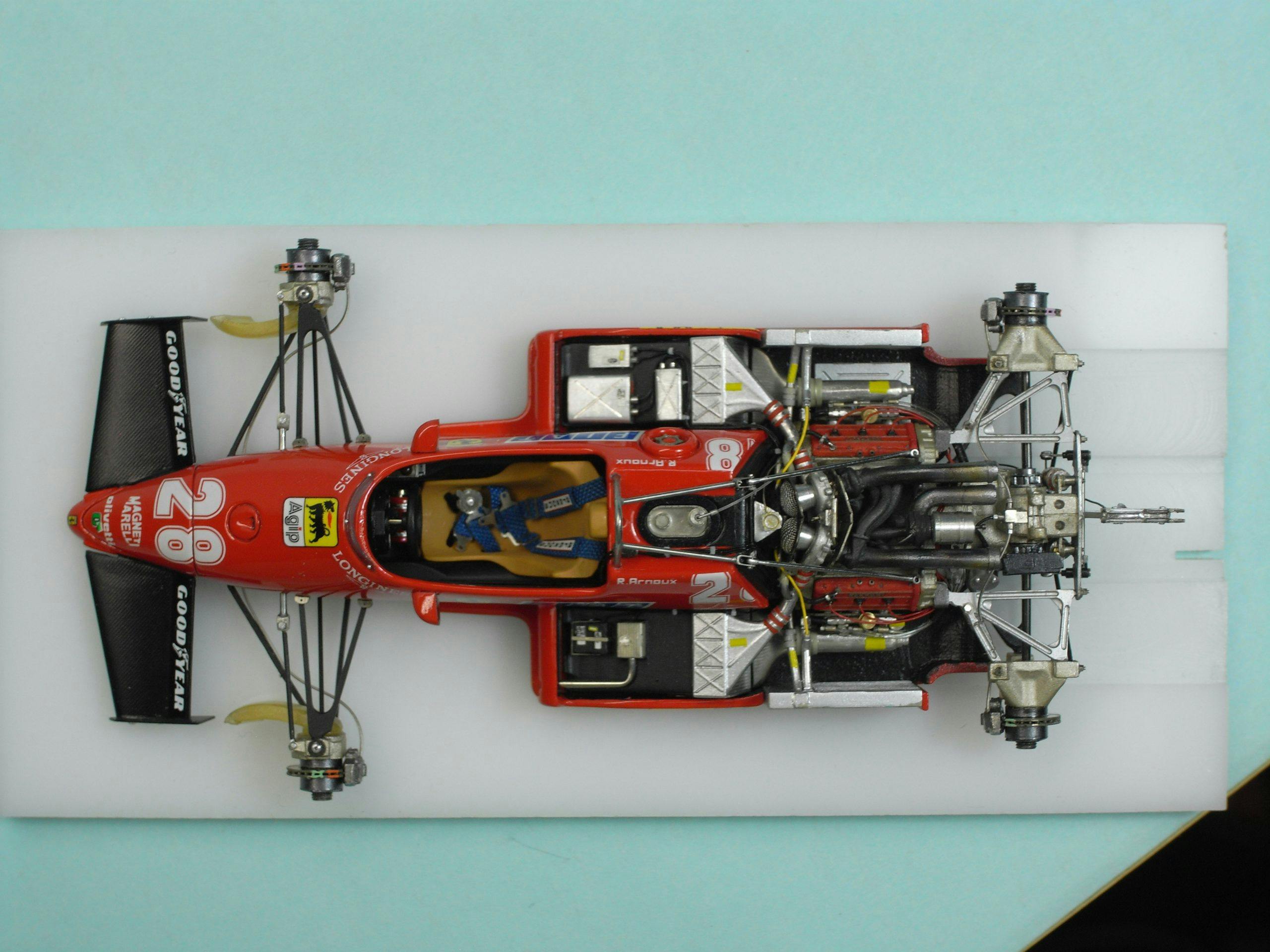

“Ruf was a model-car maker who firmly held on to a certain sense of principles,” says Barnblatt. “One of the most important to him was that shrinking a car down 43 times smaller doesn’t always make a good miniature. A sense of interpretation needs to happen when shaping the master pattern, where the ‘feeling’ of the shape of the car can be accentuated or improvised in such a way that the model takes on a life of its own.” There is no mistaking an AMR model, says Barnblatt. They can be spotted in a line up, and “Tameo took some of these principles to heart and developed his own style. Especially in his early model Ferrari kits, which are still available today.”

Nowadays, a staff of six employees at Tameo Kits S.R.L. operates out of a two-story, 8600-square-foot factory on northern Italy’s Ligurian coast, south of Turin and near the border with France. The company produces a range of kits, starting with its simplest SilverLine, which are mostly models of vintage Formula 1 cars that are oriented towards beginning builders with about 100 parts each. The typical kit includes a cast metal body and floor, plus wings, suspension pieces, whatever engine components would be showing around the closed bodywork, and wheels and tires. These kits sell for around $50.

At the opposite end of Tameo’s range is the WCT Line, which are no larger than the SilverLine kits at around four inches long but feature removable bodywork and exposed cockpits, chassis, and engines. They have around 300 parts and, in the hands of an expert builder, are the dazzling Fabergé eggs of the model world.

Compared to your typical plastic model, “Our kits aren’t exactly the easiest thing to assemble,” acknowledges Tameo. “It takes skill and excellent equipment to be able to make a finished model of good quality.” To aid builders, the company’s website features an extensive tutorial on building the kits. Some basic metalworking tools such as files, snippers, and tweezers are needed, as is good light and, especially for older folk, a jeweler’s magnifying glasses. The paints and glues also tend to be a little different from the plastic kits you may remember. A good place to start is an enclosed sports car like Tameo’s 1970 Ferrari 312P coupe, a relatively simple kit of few parts that only requires spraying the body with one color. Patience is a necessity, but compared to plastic kits, it’s easier to undo a mistake with metal and start over.

The main ingredient in Tameo kits is “white metal,” a relatively soft, pliable alloy of tin and copper extensively used in 1/43-scale kits today and which traces its hobby roots to toy soldiers. White metal remains popular with modelers because it’s easy to cut and file and it gives an unexpected heft to an otherwise tiny model.

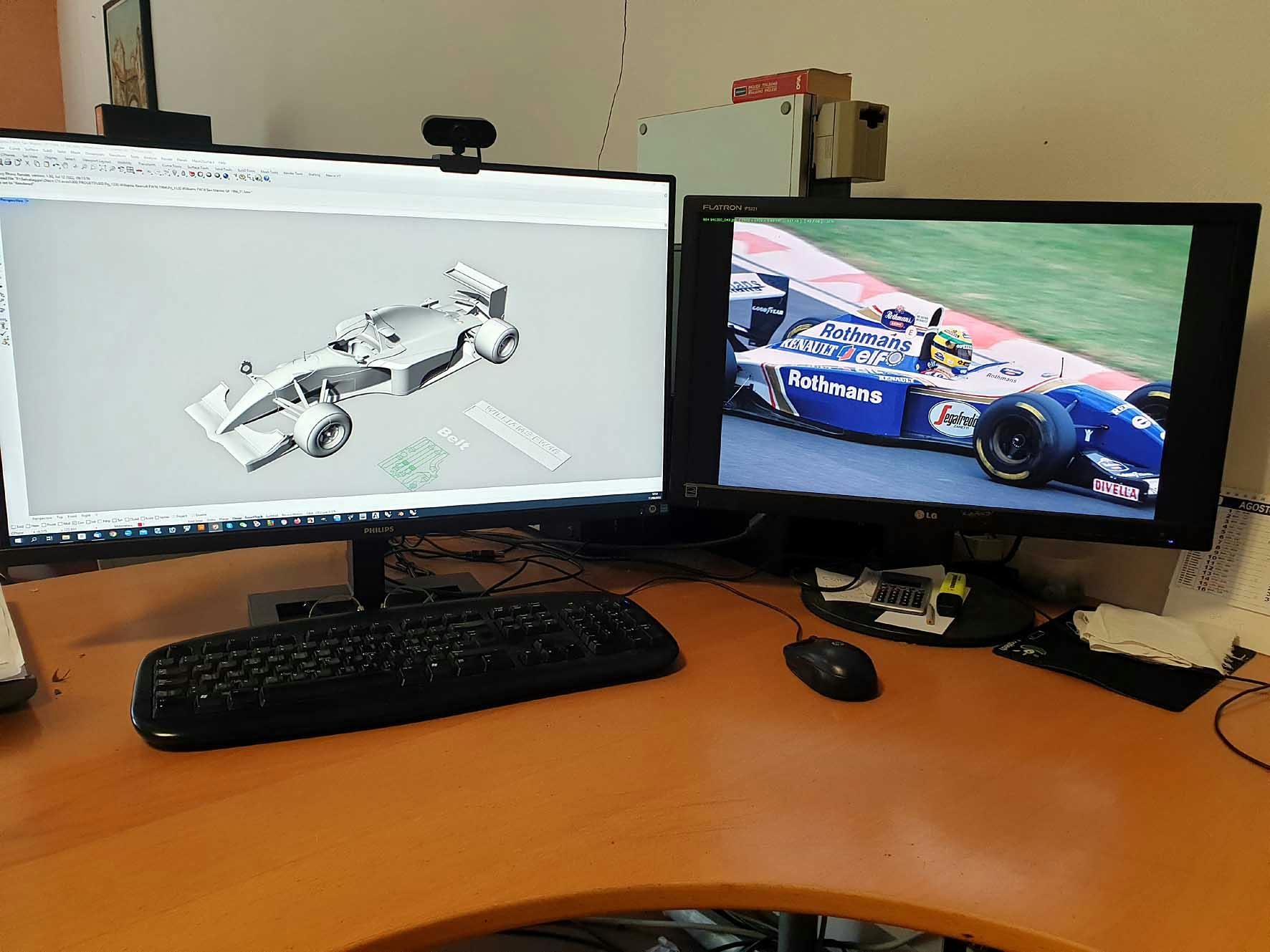

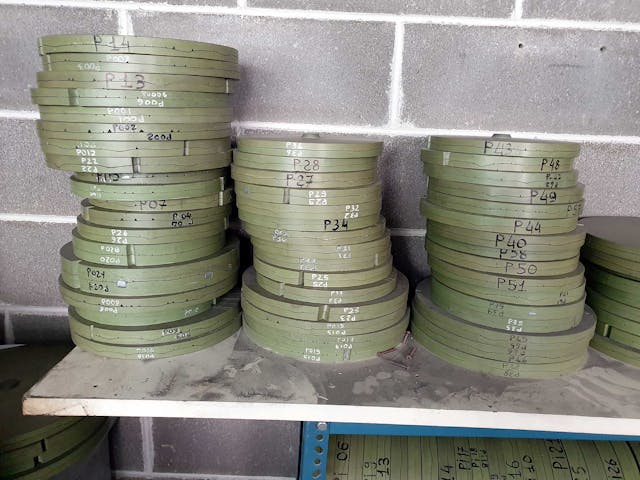

Internet research, graphic computer modeling, and 3-D printing now stand in for hand-sculpting wax masters from grainy photos in magazines and books. Tameo has spent 30 years perfecting a centrifugal casting process that involves cutting the shape of a kit’s parts into a matched pair of plaster discs, then spinning the discs at speed while molten metal is poured into the center. The centrifugal force pushes the liquid metal into fine crevices and cavities, meaning Tameo can cast the parts with more precision. They emerge from the separated discs as giant metal snowflakes of tiny suspension and brake components. The snowflakes are then cut up, the individual parts going into small baggies for the kits. Much of the excess metal “flash” is recycled for further use.

It takes Tameo about two months, “if we focus,” to design and engineer a new kit. “The choice of the models to produce is always very difficult because it is a question of ‘guessing’ whether a new kit will be successful or not,” he says. “Of course, if the choice falls on the big teams like Ferrari, Lotus, or McLaren, the guarantees of a good sale are greater. I must say that lately we have been registering great interest in minor Formula 1 cars. That is, those cars that have never won or that have distinguished themselves only for very particular designs or captivating decorations.”

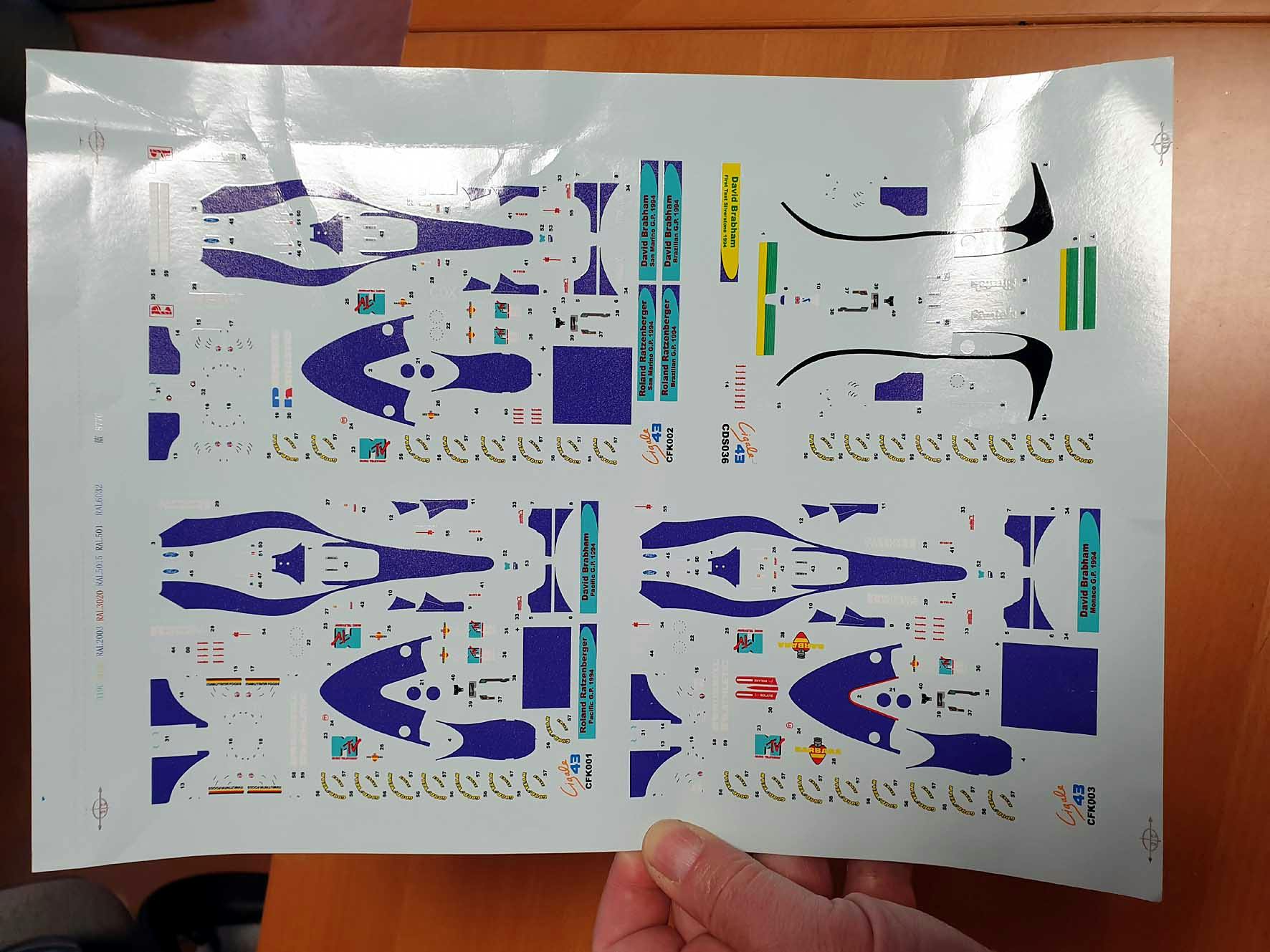

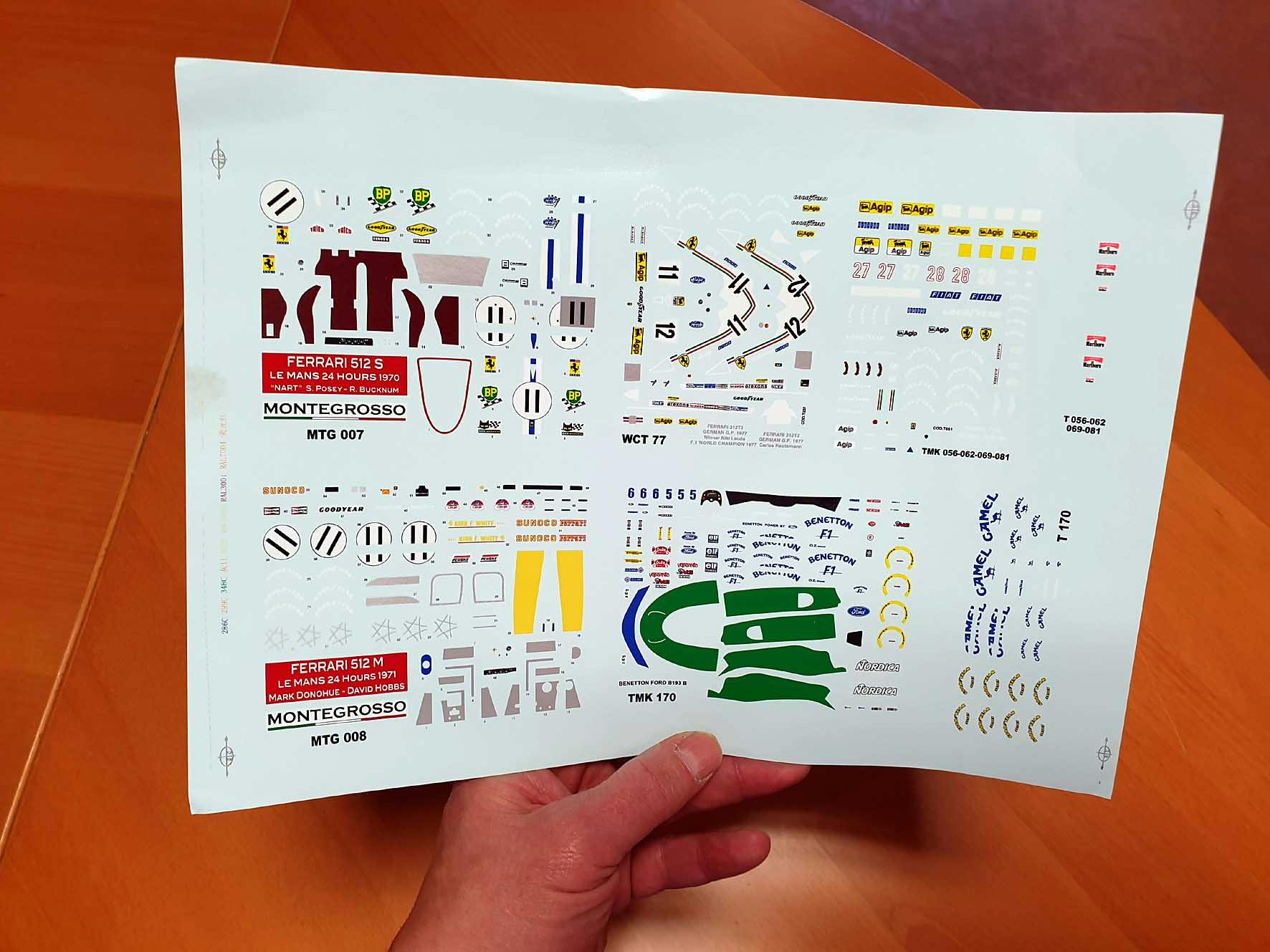

Other considerations, such as steep licensing fees, has meant that Tameo now shies away from newer F1 cars and produces mainly models of historic race cars. However, that means wading into the morass of tobacco sponsorship on older race cars. The regulatory agencies of many countries lump in model kits with toys under a blanket ban against tobacco advertising. That forces Tameo to ship its kits without tobacco logos, meaning modelers demanding perfect accuracy must go online for aftermarket decal sheets that contain the right logos.

While Tameo sells to more countries today than ever before, the overall market has been in decline for several years, he says. That’s partly because of an invasion of finished models from producers in China that offer highly detailed diecasts for the same or less than a Tameo kit. “To survive we decided not to compete with them, but to find our market niche by turning to model makers who do not like the diecast model but prefer quality, detail, and the almost total absence of compromises,” says Tameo. “I must say that, even in the face of constantly decreasing numbers, this way to produce models has proved to be a winner for us and has guaranteed us, until now, our survival.”

Another problem is that modeling hasn’t made the generational jump from older builders to younger people, who are more attracted to electronic entertainments. Says Tameo: “There are still model makers who have followed Tameo Kits since the early ‘80s, but we can’t see the right generational change because young people are no longer interested in modeling but prefer other leisure activities.”

The company has spent a lot of time updating its older catalog listings, redesigning kits from the 1990s using new technology and materials. It has also begun producing a range of accessories, such as more accurate tires and detailing bits, that modelers can use to dress up their kits.

Barnblatt hopes more collectors will be willing to venture into attempting a model kit, “which would easily become the centerpiece of their collection.” It’s one thing to have a wall of model cars, quite another to say that you built some of them yourself. Says Barnblatt: “There is a world of interesting artisan model cars out there, old and new, that can contribute to an already impressive diecast car collection.”