Media | Articles

Artist transforms yesterday’s scrap into tomorrow’s heirlooms

A diaphanous mist is swirling inland from England’s Margate seafront. Street by street it creeps. The Rag and Bone Man is coming, too. You’ll hear him before you see him, but he won’t be calling out for your scrap; there’s no room for it on his motorbike. Shoulders down and elbows in, he sits deep in the seat of a long and low two-wheeler. A product of 1950, its BSA engine emits a full-bodied, well-matured rumble that reverberates through the Kentish town. It’s approaching nine in the morning, and with an open-face helmet he can taste the sea salt in the air.

With a composure that signals he’s an easy rider, he leans into each turn. To the left and to the right, he has a hypnotic rhythm with the road, but the mist can’t match his pace. He comes to a halt alongside a painted timber door, the entrance to his workshop. Dark green, it bears the number 4. Once inside, he puts on a flat cap and switches on the lights, but not always in that order. His trade isn’t typical of the traditional rag-and-bone man: Rather than buy unwanted items and resell them as they are, Paul Firbank, an artist engineer, returns them to the economy in astonishing reworked forms. It could be a golf club or a vintage car jack, wheel bearings or bits of an old digger. Once procured by The Rag and Bone Man, everything has the potential to be reinvented.

“I work in reverse,” Paul says. “I take something that’s already made and rethink it.” A single floor lamp, for example, will comprise multiple components, each with its own curiosity but at the end of its intended useful life. In the past, Paul’s pick-and-mix of cast-offs has included road sweeper parts, Land Rover radius arms, and a classic Mini brake drum. “It’s quite an organic process. I might do an initial sketch but that usually changes as I start playing around with different bits. I figure things out as I go along—even in my sleep.”

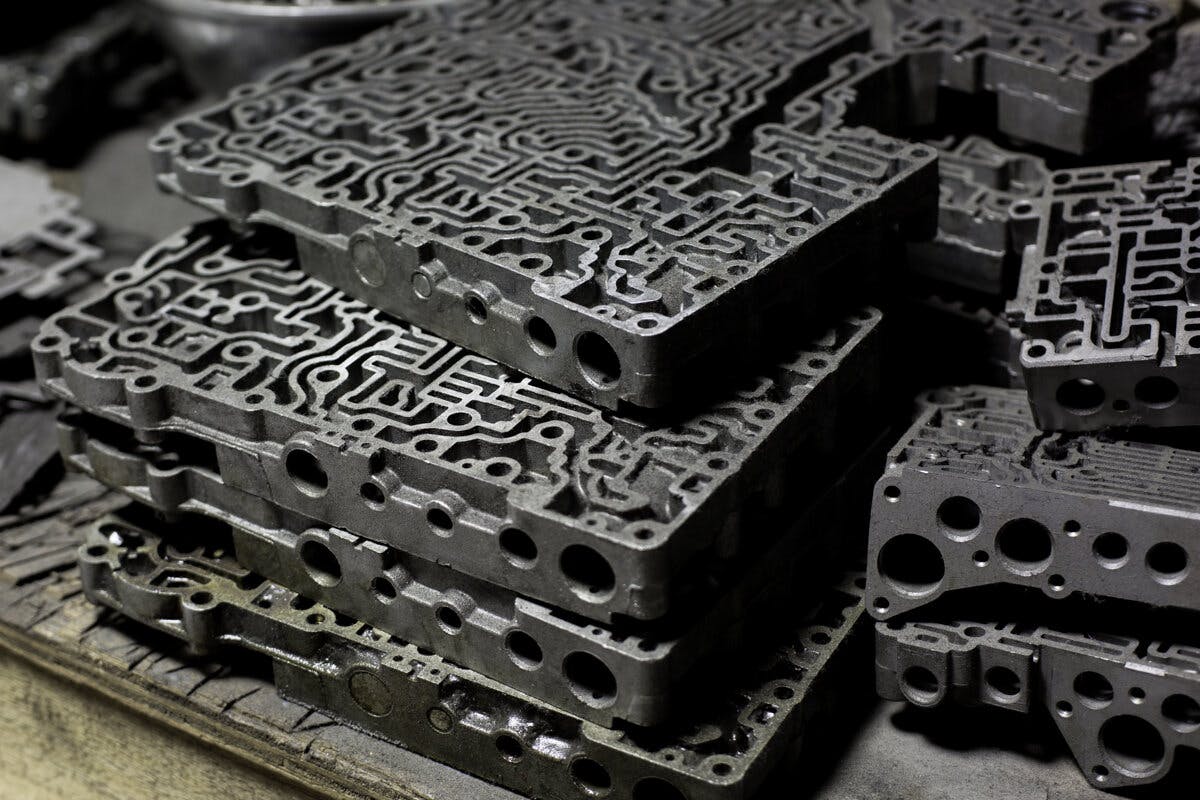

Paul’s workshop is itself a retrofit. Built as a depository in the 19th century to house the belongings of well-to-do Victorians on their summer holiday, it now heaves with vintage machinery—including a 1940s bandsaw he acquired at Chatham Historic Dockyard—and the hoardings of a “scrap-addicted madman.” There are wheel hubs that once belonged to a prewar car, clutch baskets (ideal for pendant lights), and miscellaneous lumps of cast metal. Right now, Paul is animated about a recent find. Hazarding a guess, he says: “It’s something from the inside of a boiler.” Colossal, cylindrical, and fabricated with a thick thread, the object, brutal and patina’d, is already an industrial work of art. “For me, this is a magical place.”

With over a decade in the business of repurposing often rare and one-off components, Paul has an established network of suppliers. If he’s looking for something specific, say, a radial engine—“I know a guy”—he has a little black book of numbers he can call. “I have to build up a lot of trust with fellow hoarders before they’ll let things go, because they understand the value and beauty of what they’ve got. I couldn’t bear to see the gorgeous shapes I see in scrap melted down, and they know that.”

To maintain a constant flow of new material, Paul brags rummaging rights in scrap bins up and down the country, but the most convenient is that which belongs to the motorcycle shop next door. “I’m very lucky.” The unpredictability of what he’ll discover gives rise to a heightened feeling of anticipation, but Paul has a particular penchant for items that have a compelling CV: “I’m inspired by scrap with heritage, hidden gems with an interesting story.”

Paul’s portfolio (and ambition) is anything but mediocre. Describing the gargantuan 1943 de Havilland Goblin jet engine he spent hundreds of hours transforming into a chandelier as “a proper piece of history,” it was, he says, so well made in its day that it was particularly arduous to take apart. “I had to make my own tools, including different types of pullers. As you dismantle something you realize and reflect on the craftsmanship that originally went into it.”

His wish is to work with an engine that has propelled a rocketship into space. With such sky-isn’t-the-limit ingenuity, it’s no surprise that Paul has been scouted by the makers of TV. “Yeah, I’ve done quite a bit,” he says casually. Appearances on the BBC, Channel 4, and Discovery Channel have made him a reluctant star—you can watch him remodel a 1930s Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah aircraft engine into a chandelier—but he hopes the fascination with his “waste not, want not” values and hands-on expertise will inspire others to find creative ways to rethink and repair.

Citing the gravity bike he built out of rubbish for Red Bull as the project that’s given him the biggest “kicks” to date, Paul displays a pragmatism even as he talks about the pinch-me moments. He is blown away, not boastful. The push bike “wasn’t like anything I’d ridden before,” and with no pedals, no seat, and aerodynamics tailored to make it go fast, very fast, down a hill, you’d be forgiven for thinking his invention sounds dangerous. Potentially deadly, even. “It had brakes,” he says in its defense. If you’ll forgive such a state-the-obvious spoiler, Paul and the bike—comprised of a frame that had been sculpted from a fly-tipped iron bedstead—survived their maiden descent in one piece.

At this year’s Goodwood Revival, a nostalgic three-day event that recreates the glorious days of motor racing, Paul plans to team up with apprentices from the Heritage Skills Academy—an organization that brings together experts from across the restoration industry to run courses—and refashion the wing of a Morgan motor car into a piece of furniture. “That next generation, I find them so inspiring,” he says. “Their passion is incredible. If you’re passionate about something, you’ve got to keep that going because you don’t know where you’ll end up.”

Occasionally, Paul is obliged to justify his actions; dismantling and repurposing historic items doesn’t always win votes from enthusiasts. “What have you done?” is a question, when tinged with accusation, that requires a tactful response. “I don’t butcher anything,” Paul says. “I use components as they are and add other elements. Rather than be in a museum for a select few, I give these things a new life, I bring them to different groups of people.” For provenance, each piece—“they’ve been called future heirlooms”—is given a serial number which Paul stamps on to a metal tag and attaches to the work.

The word “upcycle” is seldom used to describe the works of this modern rag-and-bone man. “Paul was doing what he was doing long before upcycling had its moment,” suggests Lizzie, his wife and partner in the business. After meeting in London and launching The Rag and Bone Man together at a design festival in 2011—“a wall of people were drawn to Paul’s work,” she says—they married on a fairground Wall of Death in 2017. Both blue-eyed and with a shared vision to design pieces that show how the characteristics and quirks of once-functional scrap can be reinvented, they are an effective and sought-after team.

Ongoing commissions include trophies that can weigh nearly 9 pounds for MotoGP, Moto2, and Moto3. “It’s nice when riders aren’t only on a mission to win, but to win one of our trophies,” says Paul, “especially when I make them a bit too heavy and some bloke who has just got off his super bike with arm pump [forearm pain that can develop after holding onto a motorcycle grip] is desperately trying to pick it up.” It’s an amusing thought, but Lizzie has a more diplomatic summation: “It’s so rewarding to see something that would be melted down become part of motorsport history.” They are well-scripted in finishing one another’s sentences.

The idea that a large proportion of the carbon fiber used in motorsport finds its way into landfill makes Paul uncomfortable. “It’s hard to get rid of and so it’s a menace to the planet.” Rising to the challenge of seeking a sustainable solution, he’s developing a way in which broken Formula 1 car parts can be shredded and metamorphosed into something useful.

“I like learning,” says Paul, whose skillset is largely self-taught. YouTube has been particularly enlightening. “I cocked up most of my school life, then I went to college and got into trouble; a mainstream education just wasn’t for me. I was destined to work with my hands.” The dirt trapped between the swirling ridges that decorate his fingerprints is a clue to the nature of his graft. “There’s a good deal of elbow grease involved in what I do.” Always on the lookout for second-hand machinery and tools, if it needs restoring, that’s not a problem.

The weathered hammer screwed to the workshop wall, you might suspect, has been taken out of service. There’s a “W” welded on its head. “For Wally,” Paul says. “My great-grandad was called Walter, and he was a metal worker in the East London dockyards.” It’s treasured rather than used. “I have all sorts of tools and machinery. I say the older the better, because they last longer.” With lathes, milling machines, bandsaws, spanners, and hammers, “lots of the kit does the same thing just in a slightly different way.” The couple have established an 1800 square foot of self-sufficient enterprise to house it all, and some of the equipment is more than a hundred years old, but there is a place for modern machinery, too. Presses, plasma cutters, angle grinders, drills—they’ve recently added a shot blaster to their assemblage and are also awaiting the arrival of a new old-style English wheel, a contraption used to fabricate compound curves in metal.

Lizzie, who had a more fulfilling relationship with academia, has an MA in fine art. Finding gratification in a less visible, more strategic role—business development, sales, and marketing, in other words±she has an intuitive understanding of The Rag and Bone Man aesthetic. “People have emotional connections to meaningful objects and to give them the opportunity to bring something that’s been stored in the corner of their garage back into focus is a really lovely thing.” Some clients, she says, like a surprise, while others appreciate a more formulated plan, but a budget is something that is always pre-agreed. A single pendant light could cost around £200 (~$240 USD), and a more complex piece of furniture in the thousands.

The midnight candle often burns at The Rag and Bone Man workshop, where the edge of the land meets the expanse of the sea. Sometimes it’s because of a workload needs must. “When I have a silly tight deadline and work 18-hour days, I’ll sleep on an old leather Chesterfield,” Paul says. But other times it’s because Lizzie is away. “It feels like home, so I’ll have the boys over and we’ll stay up drinking beer, fixing and modifying our motorbikes.”

“When you love something,” Lizzie adds, taking up the conversational baton, “you immerse yourself in it.”

Their son, Norton, at just five, is immersed in it, too, and is already and instinctually setting a similar course to his parents. “He has an amazing engineer’s mind. Designing and making is how he centers himself, and he becomes very calm,” says Lizzie.

“I don’t know how much longer I’m going to be here, but hopefully my work will be around for hundreds of years,” continues Paul. “What’s really cool is that Norton might nurture and hold on to these skills so that they can remain in our family.”

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Very cool.

Great story. Some very cool vehicles and the picture at the end with little Norton on the little red car is very cool.

I love the gas turbine chandelier and aviation sheet metal couch with matching chair. Many things can be repurposed to live on.