Media | Articles

When EVs become barn finds, what will happen?

It’s right there in the manual: don’t let this car sit for too long. But since when do people follow everything in their car’s owner’s manuals?

With gas-powered vehicles, classic car aficionados have had plenty of, ahem, time to figure out how to resurrect a car that’s been collecting dust. But we’re entering a new, more electric-driven era. And that means there will inevitably be electric vehicles that end up neglected in barns or garages. What would be better, it turns out, would be a temperature-controlled space with someone who cares enough to charge it a bit every six months.

There are many ways you’d need to treat EVs and traditional internal-combustion barn-finds the same. Flat spots on tires, grease in the wheel bearings, brittle plastic parts—that stuff is common regardless of the what powers the wheels. Yes, gas-powered cars will have more issues with anything related to hoses and fluids (oil, coolant, fuel). But the most important item to check in an EV will be—surprise—the battery. And it’s likely to have issues after sitting for a long time.

“Any time you store a vehicle with a lithium-ion battery, or really any electrochemical battery, that battery will not perform to its potential when it was new,” said Ryan Harty, manager of connected and environmental business development at American Honda.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Just how much of that potential a battery loses over time depends on a number of factors. The big three are:

- The exact chemistry of the cells

- The state of charge and usage level when the EV went into storage

- The temperature in the place where it was stored

Not all lithium-ion batteries are the same

In general, hot temperatures are worse for a sitting EV battery, said Daniel Abraham, a senior materials scientist at Argonne National Laboratory who has been working on lithium-ion batteries for over 18 years. “In our experience, cells tend to degrade faster, calendar life aging is faster when it is warmer.”

Calendar aging is the wear and tear on a battery that happens over time. Battery usage, or how many times you charge and deplete a battery, is called cycle aging. Unsurprisingly, a lightly-used battery will do better when stored for a long time than a battery that has been used to drive a car 100,000 miles.

There are a number of reasons that modern EVs use lithium-ion batteries, and potential long-term life is one of them. “The good thing about lithium-ion cells is that the self-discharge rate is very slow, but it very much depends on which chemistry you are working with,” Abraham said.

By chemistry, Abraham doesn’t just mean a broad category like lithium-ion, but the specific, detailed composition used in a particular EV. The chemistry of Nissan Leaf, Tesla Model S and Chevy Bolt EV are are all different (and proprietary), and each will show unique results if left alone for the duration of time we’re talking about. But there are some common factors to consider.

Battery degradation

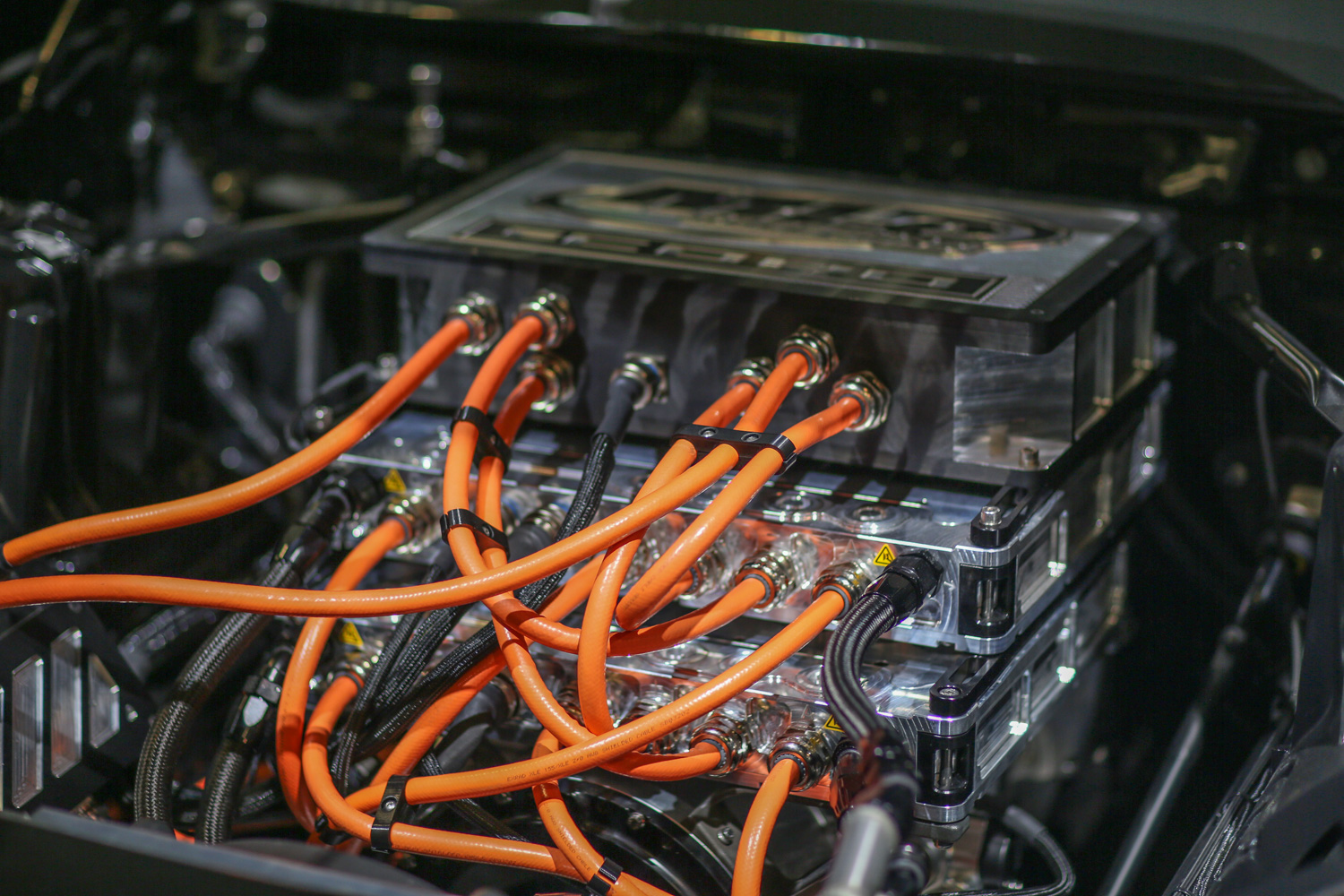

A quick refresher on batteries is in order here. The traction battery in an EV is made up of a large number of cells, each of which have two electrodes, positive and a negative. Between the electrodes is a separator and an electrolyte. An important detail when discussing long-term storage is that most lithium-ion batteries used in today’s EVs also contain copper current collectors. And it’s these copper wires that can cause problems when a battery sits unattended for too long, because of something called over discharge.

There’s a stored energy level (voltage) in modern lithium-ion batteries at which a cell is considered totally empty. This is called a cell’s cut-off voltage—typically around 2.5 volts, Harty said. When the energy in a cell drops below that level, chemical side reactions start to happen and can physically damage the battery.

“Then you’ll start to have corrosion of the copper current collectors,” he said. “The copper goes from being a solid to being in solution, floating around in the electrolyte and being deposited in other locations in the battery.” These microscopic copper wires are where they’re not supposed to be, and that can short circuit the pack the next time you charge the battery. “It’s not a safe thing,” Harty said.

Not every EV uses li-ion chemistry that contains copper, though, and these are the ones that are better candidates for barn EVs. The Mitsubishi i-MiEV and the Honda Fit, which use Toshiba cells with lithium titanate chemistry, are two examples. “With that particular chemistry,” Abraham said, “it is very likely that if you find it 20 years later, it will work just fine,” as long as it was stored with some care, like making sure the state of charge (SOC) is in the right range.

“The state of charge makes a big difference,” Abraham said. “If it’s at 100 percent, and the temperatures are high, then the batteries tend to degrade really fast so when you come back 20 years later, you will have to replace them.” On the other hand, if the car is put into storage at medium SOC (perhaps between 40 and 60 percent), it is very likely that the battery will not suffer from too much calendar aging, he said.

“[Degradation is] like filling a bucket with water, but there’s a hole in the bottom so the water will leak out,” Abraham said. “In a battery, the electrons can leak out through the system over time.”

Plug it in, here and there

Slowing down calendar aging is one reason why you need to put at least some energy into the pack—back up to around 50 percent SOC, ideally—if an EV sits for too long. How long is too long? That depends on who you ask.

For example, the owner’s manual for the 2018 Honda Clarity Electric says that, “At least once every three months, recharge the High Voltage battery.” But Honda’s Harty is unintentionally doing his own experiment to see how accurate that warning is. He owns a Clarity Electric that has been sitting in long-term storage at American Honda for about three months, because he’s been driving a Fit EV as part of the controlled charging experiment called SmartCharge.

“I’ve got a little bit of discomfort where I don’t really know how the [Clarity] is doing and I can’t check it because the 12-volt is dead, and I can’t even go out and start it,” he said. “It’s going to take some work to start that car. I’m exactly living this situation, but for a self-inflicted reason.” His confidence in Honda’s battery tech means he doesn’t expect the Clarity Electric’s traction battery to give him any trouble until maybe six months are up. That’s not quite “barn find” territory, but give him time.