Media | Articles

The last American straight-eight engine had a life fully lived

By the 1950s, the magnificent V-16s, V-12s, and straight-eights of the 1920s through 1940s that we covet today as marvels of American engineering and manufacturing were anachronisms—as exciting as stale bread. Pity poor Packard. While it and Pontiac became the last manufacturers of the American L-head straight-eight, Packard’s situation was mostly the result of general malaise and bad luck. But late in the game, Packard’s future depended on those antiquated straight-eights until it could develop a V-8 to keep up with the Joneses.

General Motors raced to the forefront in 1949 with overhead V-8 engines from Oldsmobile and Cadillac. Studebaker, and Chrysler followed in 1951—of course, Chrysler’s spectacular Hemispherical combustion engines hit a high water mark. Buick’s “nailhead” overhead V-8 debuted in 1953, and then low-priced Ford got its “Y-block” overhead V-8 in 1954. Packard could never again claim industry-leading status with its erstwhile eights, and by 1952 it was struggling to compete with the Big Three.

Even leading up to this crucial shift point in engineering strategy, dated engines, and stodgy styling and advertising were a bad combination, and Packard’s ancient East Grand manufacturing plant and bleeding revenues spelled impending doom. The yearly, mind-numbing Series nomenclature, not to mention identical cubic-inch and horsepower ratings for different engines, was a marketing nightmare.

Originally introduced in 1924, Packard’s eights were known for quality, high machining tolerances, durability, super-smooth idle, and torque-monster pull. To consumers they out-classed Cadillac and Lincoln, surviving the likes of Duesenberg, Marmon, and Pierce-Arrow, to lead the luxury field.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

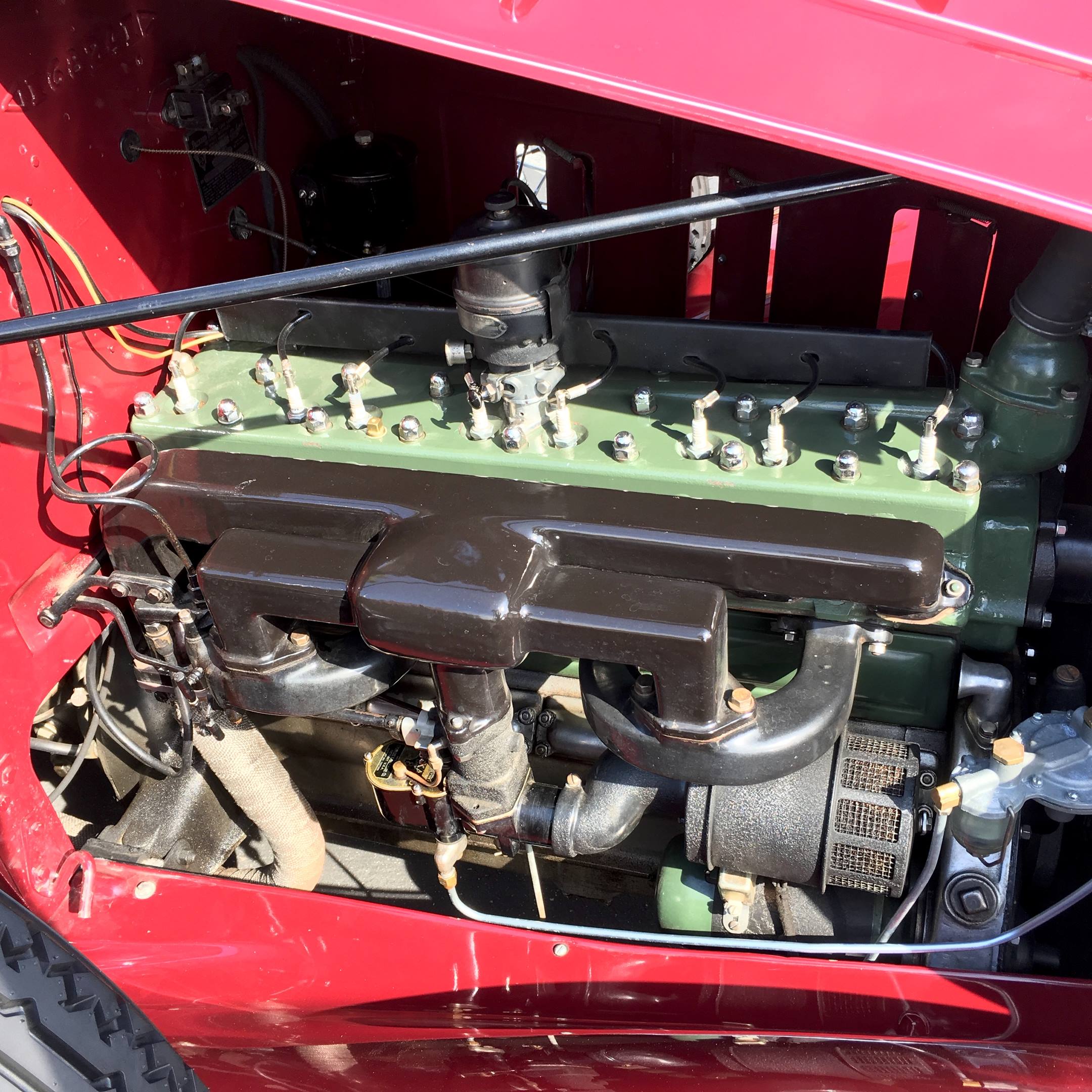

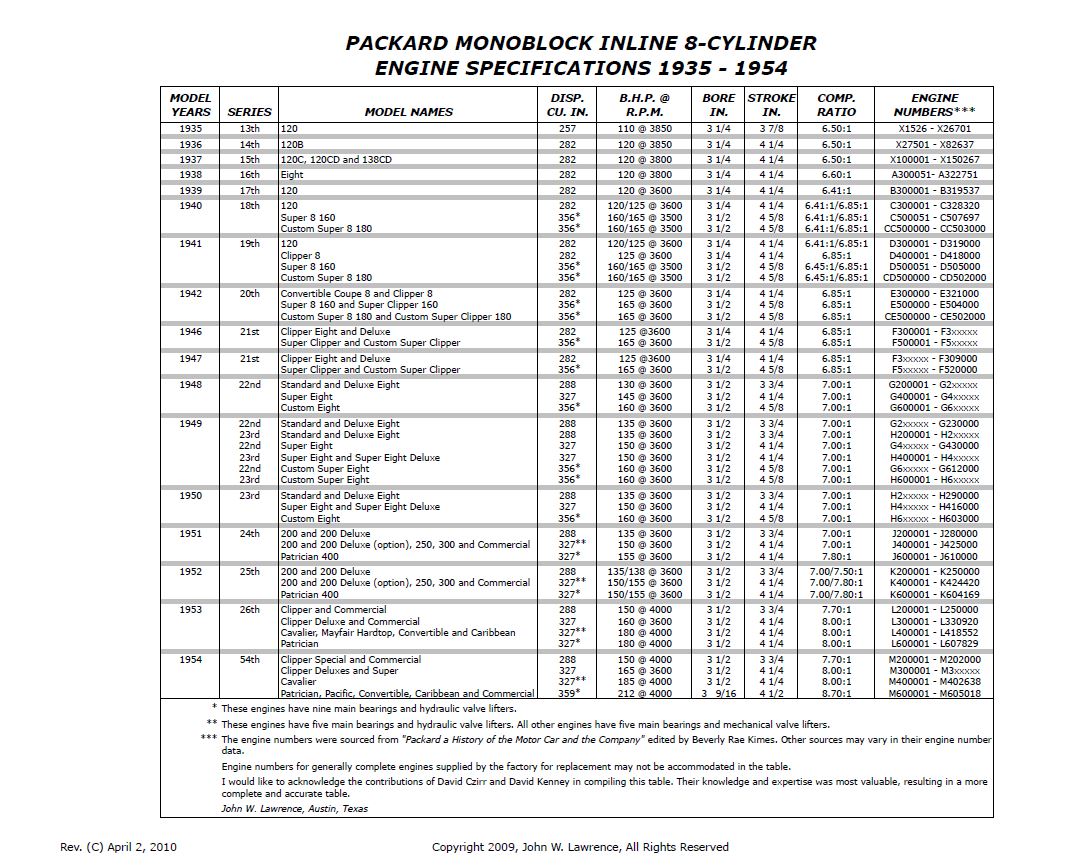

A redesigned straight-eight with an integral crankcase came in 1935, which was the basis for Packard’s eights through 1954. (There were still two “big” eights with separate aluminum crankcases; the 320-cu-in Standard Eight and 384-cu-in Super Eight, along with their 12-cylinder offerings.) The new eight featured low-compression (usually between 7.00:1 and 8.00:1 ratios), long-stroke (usually between 4 1/4-inches and 4 5/8-inches), and 125–160 hp. These were silky smooth and easily propelled the mammoth 5000-pound cars from a dead stop in high gear—which was rumored to have been advised by dealers.

After the war, Packard Standard-series eights increased to 130 hp and 288 cubic inches, with a 165-hp, 356-cu-in, nine main-bearing variant first introduced in 1940 in the Senior series. The 356 was discontinued in 1951, and the 327 was given nine mains (and hydraulic lifters) in the 288/327 block for the Patrician. Now there were two 327s—this new nine-main version, and the intermediate eight with five mains—itself a stroked 288-cu-in. Confused?

These two different 327s were both rated at 150 hp in 1953. Adding to the confusion, the 327s were upped to 180 hp at 4000 rpm, while the standard 288s were 150 hp, reflecting the previous year’s big eights. For customers comparing engines, it must have been a blur.

In racing, the venerable straight-eight held its own. For 1953 the engines placed fifth in the Pan American Road Race, with stock Packards landing in 12th and 14th, behind factory-modified Lincolns. Don “Digger” O’Dell won the AAA 150-mile stock car race at Milwaukee in a Packard, coming in second overall for the season.

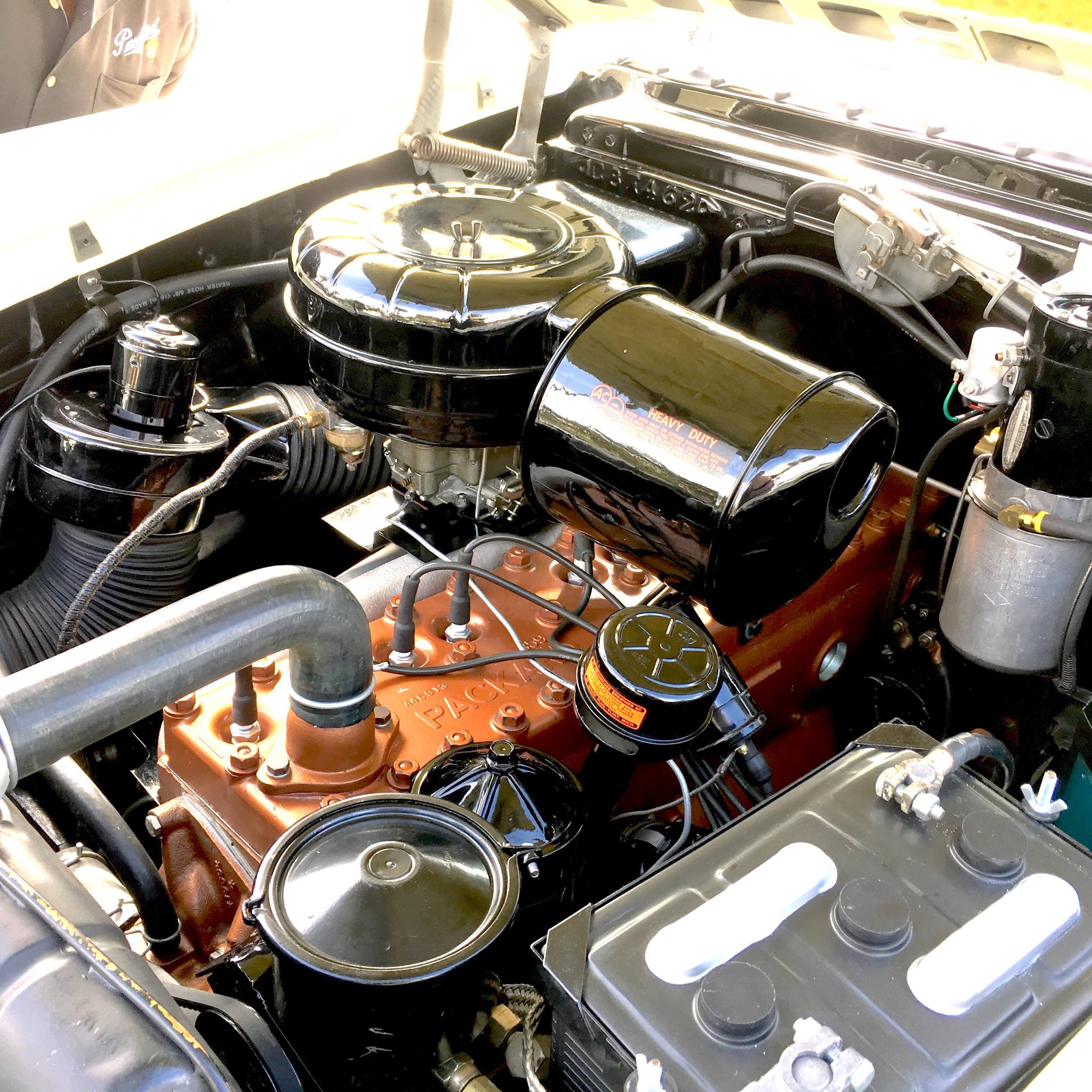

For 1954, the standard 327 was now 185 hp, while the nine main-bearing eight was punched to 359 cu in for 212 hp, its rated torque 330 lb-ft at 2200 rpm. Those specs placed it in the middle of the luxury field. The big 8.70:1 compression ratio was achieved by canting the valves toward the cylinders allowing for better breathing and valve cooling—a trick gleaned from wartime aircraft engine manufacturing. In spite of the one-year-only aluminum head prone to warpage, cracking, and warranty fixes at the dealer level, the 1954 359-cu-in engine became the ultimate straight-eight manifestation.

In hindsight, the increases across the board (3 9/16 bore—up from 3 1/2; 4 1/2 stroke—up 1/4-inch; 8.70:1 compression—up from 8.00), plus four-barrel carburetor, pushed it out to the limits. Many consider it the ne-plus-ultra of American straight-eight development, and the ultimate climax for this engine architecture.

By 1954 Packard had a V-8 design almost ready, but as sales plummeted and lucrative defense contracts shrank, development money was thin. Plans were afoot to abandon the East Grand home for a “modern” factory, and the “All-New Packard” was being developed. But 1954, and then 1955, slipped away. With credit lines gone and the Studebaker merger impending (an outfit in equally dire financial straits), 1956 became the release target.

A heavily face-lifted body was a bridge for 1955. Sales from 1954 were needed to finance the plant move, body tooling (which had been farmed out since 1940), and to quell creeping perceptions that the company was slipping into obscurity.

Unfortunately, none of it was good enough to save Packard. Even though the V-8 eventually materialized to replace the venerable straight-eight, it came too late, the new motor lasted just two years from 1955–56. Studebaker-Packard came in 1957, and in 1959 the Packard name was no more.

It’s no wonder that when people look back at Packard, it’s the endurance and polish of the straight-eight that they remember.

your article misses the mark, Packard wasn’t the only Straight Eight left in 1954, so was the excellent 1954 Pontiac 268 Straight Eight, Pontiac’s intended last year for their Straight Eight was 1952, but Buick and Oldsmobile didn’t want the 1953 Pontiacs to have it’s new 287 Strato Streak V8, so they protested to the GM’s Board of Directors, and the Board ordered Pontiac to wait till 1955, which not only pleased Buick and Oldsmobile, but also gave Chevrolet time to have it’s 265 V8 ready by 1955.