Media | Articles

How design evolution gave us the Olds Toronado from the Cord 810

Probably the most iconic shape ever created by an American automobile designer is the Cord 810 penned by Gordon Buehrig in 1934. It broke nearly every rule of conventional thinking: Front-wheel drive, nine inches lower than any competitor, no obvious radiator behind its “coffin nose,” electro-mechanical four-speed gearshift, four constant velocity joints in the driveline to both steer and power the car, and a supercharged option to the brand-new 288-cubic-inch Lycoming V-8 engine.

Rushed into production in under four months in 1936, the new model was plagued with transmission troubles and the company’s rocky finances meant that automobile production was canceled only 18 months later. Only 1174 examples of the 810 and 1146 of the Supercharged 812 model were built in sedan and convertible forms. The company’s subsequent bankruptcy meant that enthusiastic owners were left with no service support and an uncertain parts supply. Nevertheless, almost all 810s and 812s survive.

Fast forward 30 years to a most unlikely successor, the Oldsmobile Toronado. Olds was celebrating its 60th anniversary in 1963 and designers were chafing under the reputation of “your father’s car.” GM had been toying with the idea of a Unitized Power Package as early as 1955, when a staggeringly ugly, non-running front-wheel drive La Salle concept was displayed. By 1958, a working FWD example existed, powered by a monster 429-cubic-inch V-8.

Oldsmobile designer John Beltz was fascinated by the potential for the FWD V-8 layout and was convinced that the division could regain the mechanical initiative it had shown with the Hydra-Matic Transmission of 1941 and lightweight OHV Rocket 88 V-8 of 1949. The first FWD design was based on the F-75 compact of 1961, but the idea soon grew into a full-size model in 1962, and Project XP-784 was born.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

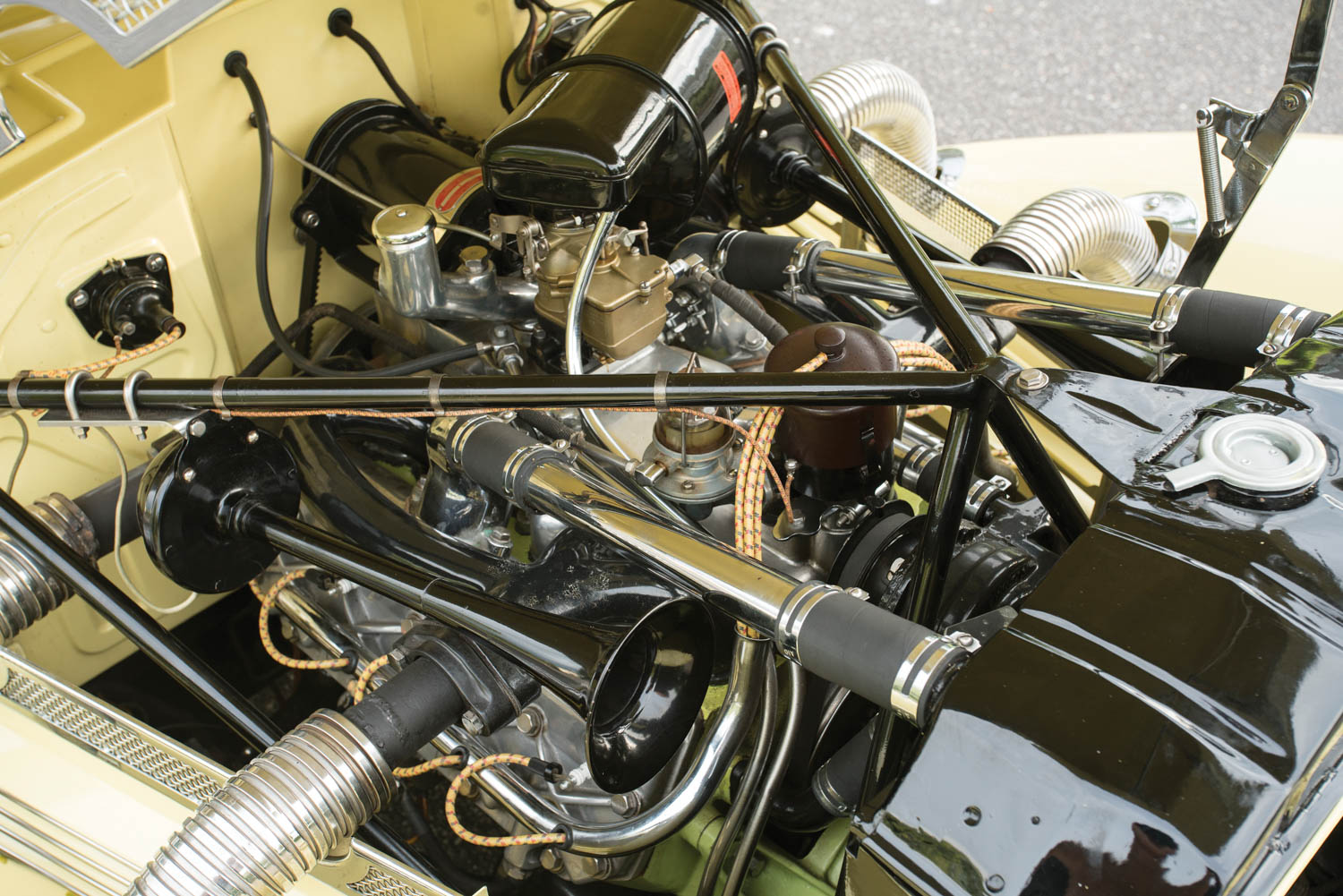

The driveline represented spectacularly original thinking: The 385-hp, 425-cubic-inch V-8 engine was positioned longitudinally, and the torque converter transferred the power sideways to the Turbo Hydra-Matic transmission by a pre-stressed chain, which was cushioned against engine pulses. The transmission was placed alongside the engine and connected to a spiral bevel differential to drive the front wheels. The engine’s oil pan had a hump in it to clear the front axle, and the front suspension was designed with torsion bars instead of coil springs. The power unit was mounted on its own sub-frame, while the rest of the car was unibody, and a solid rear axle was located by single leaf springs.

The Toronado’s design was based on a clean sheet, and one full-size red-painted rendering by assistant designer David North. The name was borrowed from a 1963 Chevrolet concept and had no other meaning. The new car appeared to owe nothing to any contemporary, except the blade-like front fenders used on the striking 1961 Lincoln Continental. Proportionally, it resembled the similar E-body Buick Riviera with along hood and short deck, but radical elements included exaggerated wheel arches and long-low styling lines connecting them.

GM design head Bill Mitchell lost the battle for a smaller A-Body Toronado and the final design featured a huge 119-inch wheelbase. Interior space was excellent, thanks to the flat floor, but the smooth fastback restricted rear headroom. The front Strato Seat featured separate bucket uprights and a common bench with folding center armrest. Doors were massive at 37-inches long and had rear interior handles, so rear passengers could exit. Instruments were grouped in front of the driver and were anchored by a “rolling drum” speedometer which was easy to read until the cable wore, in which case it was as illegible as the Edsel “compass.” Eliminating vent windows meant the new model was significantly quieter at speed, with flow-through ventilation

Mechanically, the Toronado was an outstanding success, with 54/46 weight bias and neutral handling. It was Motor Trend’s 1966 Car of the Year, capable of 0–60 in 7.5 seconds, a 16.4-second quarter mile at 93 mph, and a top speed of 135 mph. Cord styling cues included hidden headlights, a ribbon grille, and 3¼-inch dished wheels, which were drilled to cool the overworked drum brakes.

Disc brakes were a welcome addition in 1967, which was the last model to resemble the original concept with an egg-crate grille, though the “letterboxes” above the headlights were smoothed over. The new model featured improved geometry, which was easier on front tires. For 1968, the Toronado appeared to have swallowed a mouth organ and the design struggled until it was replaced by 1971’s cubist experiment.

The Toronado was a big success in 1966, selling 40,963 examples, against the conventional rear-wheel drive Buick Riviera’s 45,348 units. But Toronado sales plunged 50 percent to 22,062 in 1967, partly due to the introduction of Cadillac’s very similar FWD Eldorado, which recorded 17,930 sales, probably at Oldsmobile’s expense.

Just like the Cord 30 years earlier, the Toronado’s design was polarizing. Most people admired its style, but such radical mechanical thinking deterred a number of buyers who remembered Cord’s faulty constant velocity joints. Ironically, Oldsmobile actually solved the Cord’s problems, when engineer LeeRoy Richardson adapted the new Toronado CV joints to the original Cord driveline.

At present, 1966–67 Toronado prices seem to languish. Just like Cord 810/812 aficionados, many original buyers held onto their cars, not as investments, but just because they like such strikingly original thinking. A very sound, if tired, 1966 Toronado only attracted a $2500 bid in Seattle recently, and even the best survivors struggle to attract interest in the $15,000–$20,000 range, which they would seem to deserve.

While Hagerty rates 1966–67 Toronado values from $42,200 for a #1 car to $8600 for a #4, solid survivors can still be found under $10,000. The principal problem may be finding a big enough garage to store a 4496-pound, 18-foot “personal luxury coupe.” Any ground-up restoration would be an act of faith, as was a Cord for many years.