Media | Articles

Footnote to the 24 Hours of Le Mans, 1963

Playing with cars

In 1963, the story of the World Sports Car Championship was one of Ferrari’s dominance with its mighty 250 GTO. By the tenth round, the annual running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, it was clear nothing could touch them, and in fact, Ferraris finished the race in the top six places.

Far from the glamour of the fast end of the grid, where the 3-, 4-, and 5-liter cars did battle, the list of entries officially “not classified” in the record of the 1963 24 Hours of Le Mans contains just two cars: the experimental Rover-BRM Turbine of Graham Hill and Richie Ginther (which did 310 laps and ran well enough to have finished 7th had it been something a bit more… conventional); and the tiny and distinctively French René Bonnet Aérodjet LM6, with Renault power, which completed 211 laps.

There was a third car, however, also not classified on the day but purged for the last five decades in an unfortunate post-race clerical error. Edward Kincaid’s strange little Jaguarsche SWB Aero never made it off the grid. These were the days of the drivers’ dash across the track, the frantic starting sequence, the furious surge from stationary to wide-open throttle. It was in the last bit that things went south for Kincaid and his car.

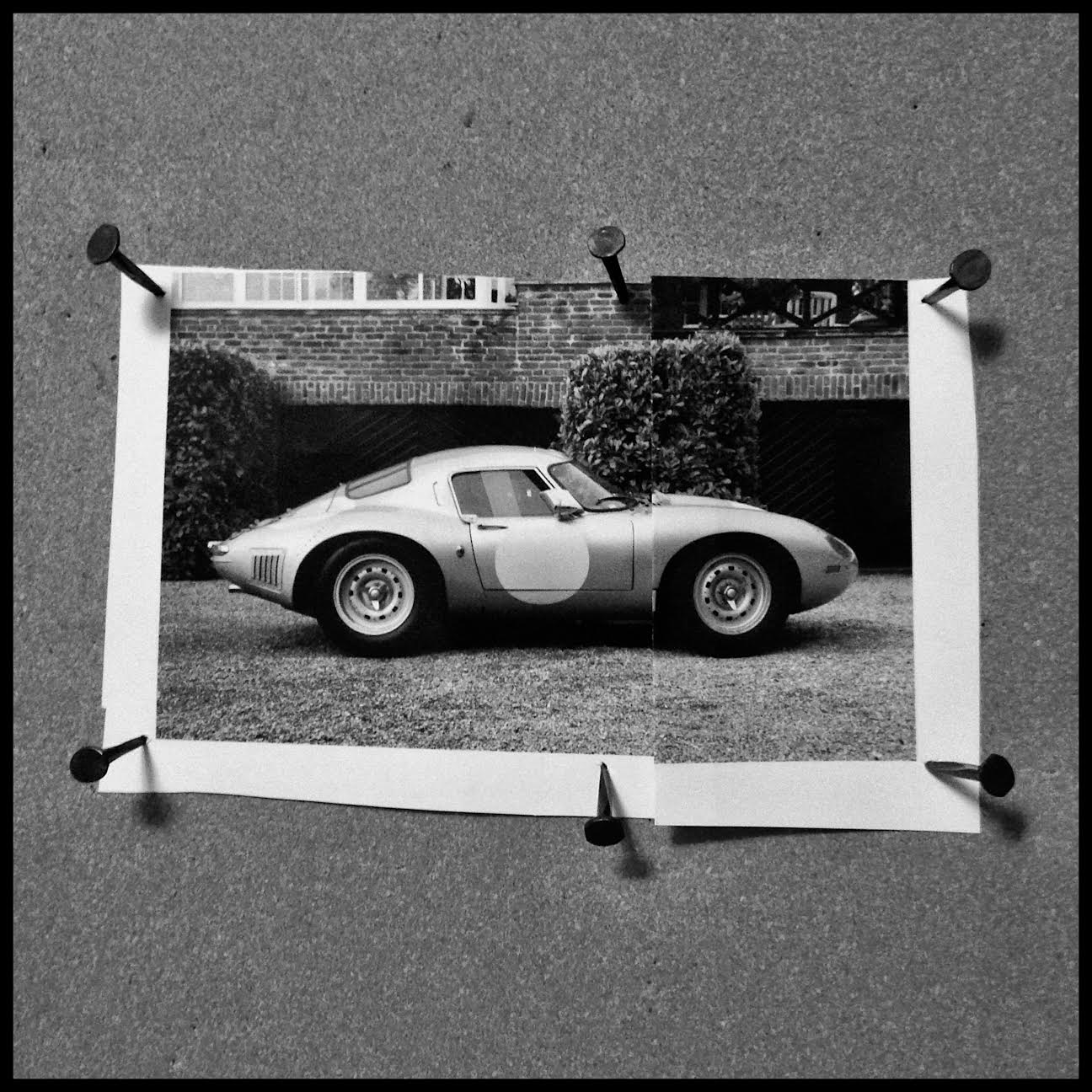

The SWB Aero was the eccentric Kincaid’s even more eccentric vision of the perfect racecar, and the British banker and sometimes-gentleman racer spared no expense to make his dream a reality. He engaged tiny Putnam Race & Fabrication of Liverpool to do the build, which required removing 15 inches, the entire straight-six driveline, and nearly everything else from the chassis of a standard E-Type Jaguar. Fascinated by Porsche’s successes with small-bore, horizontally opposed engines, he purchased and had Putnam finagle an incredibly complicated 2.0-liter four-cam Porsche boxer (Type 587) into the back(!), and then oversaw fabrication of a fiberglass body to cover it all.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The result was a comely little car with a bulging front hood that accommodated the fuel tank and a tail that finished in a near-perfect point. It was arguably better proportioned than the tiny-wheeled, sharp-at-both-ends Aérodjet and at least as appealing as the 356 Carrera it only partially paid homage to. But the question most asked in the weeks leading up to the race, and indeed on race day itself, was WHY? Who would do such a thing just to do it?

Kincaid took an odd pride in being the answer to that question, and in a three-page profile that appeared in Le Monde early that summer, he is quoted as saying, “I am quite rich, quite unattached and quite devoted to the present task. I own and drive Jaguar and Porsche both, and it was little more than a personal challenge which arose out of boredom, to marry the two marques in whatever best way I could endeavor.” Retrospectively unrealistic in his pursuit, Kincaid believed that “placement in the top 10 is attainable.”

The starter’s flag fell at 4 p.m. that June day, and 50 drivers sprinted to their cars; 49 drivers fired them up and roared away. Only Edward Kincaid and his Jaguarsche SWB Aero remained on the grid. The car would not turn over. No spark, no fuel, nothing. In the loud and smoky haze of the start, he signaled furiously to his hired French crew and the car’s builder, Richard Putnam, who pushed the Jaguarsche back to the pits for work. Despite their best efforts, they never did trace the problem and, post-race, said only that the racecar suffered a catastrophic failure.

Following Kincaid’s departure from Le Mans, the Jaguarsche SWB Aero was not seen again. He is rumored to have had the car destroyed that summer (one wild account claims that Kincaid hosted a party at his estate, where he and select guests took turns bombarding it with cannon fire), and Kincaid himself never returned to racing in any Jaguar, Porsche or otherwise.

Playing with Cars is new automotive fiction from Hagerty. No cars were harmed in the telling of this tale. See more folded paper and short fiction at instagram.com/shortcars.