Media | Articles

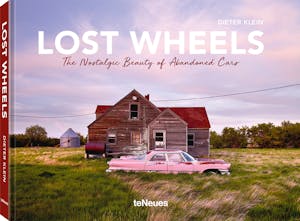

Dieter Klein travels the world in search of the perfect abandoned car photo

For a photographer who spends half his life traveling the world in search of abandoned cars, it should come as no surprise that one of the favorite photographs captured by Dieter Klein was in nowheresville.

“It was the last corner of America, really in the middle of nowhere, six miles to Canada, 20 miles to North Dakota, in a town with six houses. There is nothing; nobody who cares about anything. So it meant that the abandoned car could be left and would remain forever untouched by anybody.”

The car in question is a 1960 Dodge sedan (pictured above). It sits in front of an empty clapboard house. You can’t tell how it got there, because the house and car are surrounded by grass. There’s no driveway, no parking bay, no garage. Slowly but surely, nature is reclaiming the house and the car. The paint on the property’s cladding has almost vanished. Just a few flakes here and there in sheltered corners remain, and a little at the foot of the porch door. The dusky pink paintwork of the car is turning a shade of copper-red, predominantly on the roof, trunk, and hood, the flat surfaces where the elements can take hold. The grass obscures the bottom half of the car, lazily brushing against the metalwork in the breeze.

Klein had been searching the area, drawn by a pair of old grain silos that caught the sunset one night as he drove past to his motel. That’s when he caught sight of the scene that now graces the cover of his book, Lost Wheels, The Nostalgic Beauty of Abandoned Cars.

As is his method, Klein set about tracking down anyone with a connection to the property. He doesn’t photograph a scene without the permission of land or property owners, partly out of respect and partly because he wants to learn the story behind the scene, something the German says is lost on today’s young generation of photographers.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“At exhibitions, they just want to know, ‘Did you make the image on Photoshop?’ and when I explain it’s a real photograph, their next question is, ‘Where is the car?’ so they can go and photograph it. “So I tell them, ‘I travelled 44,000 miles in total. So I can tell you where this one scene is, but you will have to fly for perhaps 12 hours, drive maybe 2000 miles, and perhaps it’s still there or perhaps it’s been cleaned up,’ and normally it’s the end of the discussion.”

For his book, Klein estimates he spent 240 days traveling and on location, which accounts for around 10 percent of the time he devoted to it. “The other 90 percent is research.”

So there he is, in the middle of nowheresville, near the U.S.-Canada border, knocking on the handful of doors in the area, when he meets Dale. Dale’s father had parked the Dodge in front of his house two days before he died. That was in 1977. Dale, now over seventy himself, had no use of the car or the house, and chose to leave the scene undisturbed—a memorial if you will—out of respect to his father.

“It is really fascinating,” says Klein, “so emotional; why should they store this car?” It wouldn’t happen, I venture, in European countries such as Klein’s home nation of Germany, or in Britain; the local council wouldn’t allow a property and car like the setting in Montana to stand derelict and open to passers-by. “Yes, officials would come directly and clean it up.”

Where it started

Now 63, Klein has been a professional photographer for more than forty years. As a teenager, he dreamed of becoming either a piano player, a graphic designer, or a photographer. He says by the age of 17 he knew he wasn’t good enough to become a piano player, and his drawing and illustration skills weren’t up to scratch to see him through a career in the design industry. So he turned to photography, working for regional and national newspapers, and later specialist trade publications. But he says that all the way through that period, he searched for themes in his work, whether capturing industrial scenes or recording interviews with artists.

In 2008, something unexpected happened. Klein took a holiday with his wife in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, south west France, and stumbled across a 1935 Citroen Rosalie 7U. The 1.4-liter engine had been switched off for good decades ago and the car had been overwhelmed by Mother Nature, a tree growing up through the floorpan and through the steering wheel, as though it were the ultimate deterrent to anyone intent on removing it.

“You have to imagine,” recounts Klein, “that we were riding bicycles, and as we rode back to our hotel we passed an abandoned farm. There were standing some old Peugeot cars, a 203 or 303, and they were overgrown by plants. I said to my wife, ‘When we leave this village, I will come back with my camera.’ So I stepped out to look at these old cars, and I just looked around the edges of the farm and there, in the middle of an elder bush, was another car. I figured out perhaps it will be from the ’40s or ’30s, and imagined it had been standing for a very long time. It was so untouched. I had the imagination that it was like an illustration from a fairytale book, because it looked like another world. I was hooked by the motif, and as soon as I went home, I found another three or five cars, standing in nature. The artistic theme has remained unchanged to this day.”

Little did he realize that it would lead to a journey of self-discovery that would see him travel through five European countries and 39 U.S. states, with more trips in the making. Along the way there have been five related books, multiple awards at photography competitions and countless international exhibitions.

Forest punk

Those early scenes are, to my eyes at least, the most striking section of Klein’s work displayed in his latest book, which, at almost one and a half kilos, is a hard-back coffee table affair that’s assured to capture the attention of visitors.

He coined the phrase Forest Punk to describe what he was seeing—decay in a natural environment. The manmade objects have been stripped bare of their industrialized sheen. Images taken in southern Belgium have an otherworldly, almost fairytale quality, as though you’re on the set of a fantastical Tim Burton movie. Yet it’s entirely natural.

Just as natural are the images. Klein does not retouch any of his photos. The hard work, he says, goes into framing the scene and setting the exposure. Once at a location, he will work out a shoot list and plan the composition of every photograph. That’s vital, because with such long exposure times there can be no room for improvisational quick shooting.

“I always work with a tripod. Sometimes the exposure is seconds, sometimes minutes, but whatever it is using a tripod means I can fix my motif [composition] and I do all my framing on location. Sometimes, in very dark woods, I make an exposure for three minutes, and the contrast will be low, so I may have to adjust that so it can be printed, but the only correction I make is to tonal values. If I were to make changes to my pictures, and start manipulating and editing, I would destroy my ideas and people would say my pictures are faked. They have to be authentic.”

He uses digital equipment—“I was one of the first to change, because I was very fascinated that you get your result in two seconds”—with medium format cameras capable of producing a 100 megapixel image. “It’s not necessary for a book like this. But the size of the images, the tonal values and the contrast of these big backs is fantastic,” enthuses Klein.

For those amateur photographers interested, Klein only uses Phase One cameras. He switched to the Danish brand early on in his endeavors recording abandoned vehicles, after spending 25 years using Hasselblad equipment before experiencing a problem in the field and getting no help “or even an acknowledgement” from the Swedish camera manufacturer.

When Klein started out, the internet was of no use. All his detective work was done the old-fashioned way, asking friends, consulting photographers, scouting locations, writing letters, and knocking on doors. Over time, as the technology has leant a hand, he has seen locations laid to waste—in one instance after details were leaked out by others with looser lips than Klein, resulting in regional television stations declaring sites a health hazard and alerting authorities to the location.

The people behind the photos

The people behind the cars and locations are as much a draw to Klein as the inanimate subjects shown in his book. Just enough detail is shared in the book to keep you in the picture, without giving anything away to other, perhaps less respectful, treasure hunters.

Such as the story of Michael. In 1986, Michael’s father suggested his son “do something special” to mark his 50th birthday, at the turn of the millennium. So Michael set about buying up 50 different makes and model of cars that were all built in 1950—including the Porsche 356 pictured above—then arranged them, like a sculpture park, in his garden. When he reached 50, Michael, a car dealer, invited 1000 guests to celebrate with him. Today, you can see the collection for yourself, paying an entrance fee to tour the perishing cars at the weekend.

Are characters like Michael different to the rest of us? What motivates someone like that to express themselves in such a way?

“Oh, I think you have to ask psychologist! I think it’s a mixture from a narcissist—he wants to be a person who everybody talks about—and perhaps it’s a good kind of [advertisement] for his shop. He’s a little bit crazy and wants to leave a footprint in history—the guy with a car-sculpture park who left 50 cars to rot!”

He laments the position photography finds itself in today, where so little value is placed in the art form—“you have website selling photographs for one pound or two Euros now”—and divides his time between commercial work and his Abandoned Cars project.

Those poring over the index of his book in the hope of planning location visits of their own may be disappointed. Klein assures me that where someone asks for him not to reveal a location, he keeps it a secret.

We return to the cover image of Lost Wheels. Why that photograph, I ask? “For me, it expresses everything inside that I wanted to show. It’s contradictory, it’s calm, it’s peaceful, and it’s a kind of photography style. So for me this is a big shot.”

Rest assured, if you treat yourself to a copy of the book, you will be able to savor several hundred pages of big shots.

Lost Wheels – The Nostalgic Beauty of Abandoned Cars by Dieter Klein, published by teNeues, $55.00