Media | Articles

Jim Mederer: The Regent of the Rotary

A German inventor created the rotary engine. A team of Japanese engineers got it to work. In 1992, one American made it fly. Screaming across the Bonneville Salt Flats at more than 220 mph, a 760-hp, triple-rotor RX-7 suddenly spins, then flips into the air. The car slides on its roof for what feels like forever, then comes to a halt. A tall, white-suited figure pulls himself from the wreckage, yanks the fire-suppression systems, then strides from the debris like Chuck Yeager walking away from a downed test aircraft.

That man had the right stuff. He was engineer and test pilot both, a mechanical genius with the skills and bravery needed to master some of the fastest Mazdas on earth. Any fan of the rotary engine should know his name as part of the holy trinity of the spinning triangles: Felix Wankel, Kenichi Yamamoto—and Jim Mederer.

Born in 1942, Jim Mederer trained as an engineer, and then joined the Air Force. He spent his weekends racing and wrenching on his own Formula Vee and Formula B cars, but was looking for more. Fresh out of the service, he showed up at the offices of a new racing outfit called Advanced Vehicle Systems, in June 1969.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

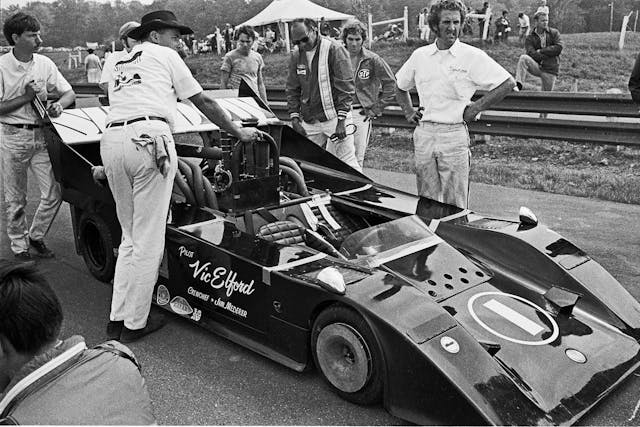

If you’re not familiar with AVS, you will perhaps know the team better as the Shadows. Mederer was there from, essentially, the beginning, first as a sort of do-everything go-fer, and later as the team’s crew chief. Shadows was an unconventional team trying out wild ideas in Can-Am racing, and Mederer learned by doing. He also picked up a tendency for always wearing a cowboy hat in the pits, emulating Carroll Shelby.

The Shadow team had a disappointing 1970 and ’71 season (though it would later find success in Can-Am and F1 racing). However, Mederer would gain more than mere experience from his time there. One of the team’s mechanics had family in Japan—team owner Don Nichols was a central figure in the nascent Japanese racing scene, including hiring Stirling Moss to help build Fuji International Speedway. The Shadows thus had a following in Japan, and one Japanese racer was looking for a business partner with engineering acumen.

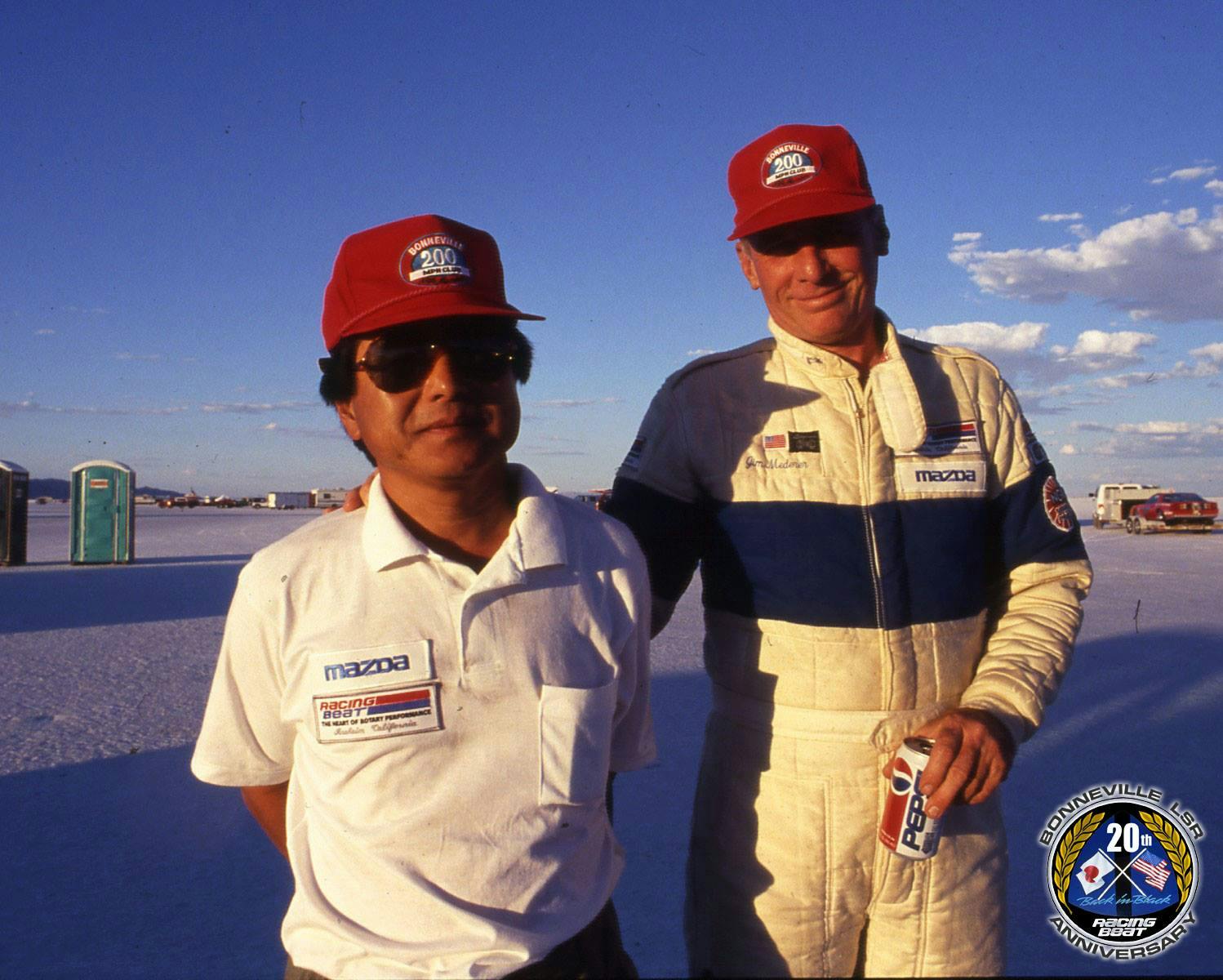

Jim Mederer and Takayuko Oku met over milkshakes in Anaheim, California, a stone’s throw from Disney’s theme park. Their partnership, Racing Beat, would go on to become a Magic Kingdom of howling rotaries, with countless racing successes, landspeed records, and huge aftermarket support for anyone who wanted to make their Mazda quicker.

Racing Beat’s first success arrived in 1972, when Patrick Bedard, then executive editor at Car and Driver, came knocking. Bedard was looking to compete in the IMSA Racing Stock series in a Mazda RX-2. The little Mazda had an optional two-rotor engine, with an unknown performance potential. Bedard asked Mederer and Oku to try to double the power output, from a stock 95 hp to roughly 200 hp.

Tuning a rotary engine is still very much an art form, and in 1972 it was practically black magic. You can’t really even call it hot-rodding, as the Wankel has no rods, just triangular rotors spinning through a peanut-shaped combustion chamber.

But Mederer appears to have been blessed with the sort of persistent mechanical genius found only very rarely, as with Erhard Melcher of AMG. In Mederer’s garage, late into the evenings, the Mazda 12A wailed its heart out on the dyno. Mederer honed the side ports until they gaped, with a metal bridge in place to keep the rotor’s seal from disintegrating. When fitted with a racing exhaust, the RX-2 made 218 hp at 8400 rpm and sounded like a banshee in an industrial blender.

The car qualified on pole so emphatically that race organizers lumped on a 300-pound penalty. It didn’t make much difference, with the RX-2 still winning two races in the season. Of Mederer, Bedard said, “A straight-talking, no-BS kind of guy. I think the most honest man I ever worked with in all my years of racing.”

Author Pete Lyons, who recently published a book on the Shadows team, recalls meeting Mederer up near Big Bear, California. Mederer was building a home in the mountains at the time, and Lyons says he walked into the cabin to see Jim’s mother, in her 70s at the time, perched atop a supporting beam, nailing rafters together.

“That’s the stock he came from,” Lyons said. “The hard-working, get-it-done approach.”

Through the 1980s, Racing Beat would record wins at the drag strip, in GTU and GTO racing, and at Bonneville. Often on the salt flats you’d find Mederer both under the hood and behind the wheel.

He left his mark. In 1995, two rained-out years after his spectacular crash, the Racing Beat team returned to the salt with a Mazda RX-7, repainted with a “Back in Black” theme.

Mederer was ready to step aside if the team wanted a pro driver, but Oku insisted he remain behind the wheel. The car averaged 242 mph, a class record that still stands today.

Beyond the speed and the engineering, Mederer was a man of devoted faith, a reliable friend, and often helped out young racers on their way up. He was also an experienced pilot, often flying up to visit his mother in Big Bear in his wickedly fast Glasair aircraft. He was also known to have a love for Motown music and would occasionally pop a move or two in the Racing Beat workshop, much to the surprise of those who knew him only as a straight-shooting, nose-to-the-grindstone type.

He died of cancer on December 27, 2016. The rotary enthusiast community responded in unified tribute to their fallen hero. Countless stories of Mederer’s patience and willingness to help anyone who needed it were blended with tales of performance, of iconel exhausts glowing white-hot on the dyno, and of his often-present red Bonneville Record Holder baseball cap.

For those who love the rotary engine, or just fast Mazdas in general, Mederer’s legacy looms large. He helped put Mazda performance on the podium, and through him Racing Beat also enlivened many a street car.

He had the right stuff: hard work, know-how, bravery, and integrity. Jim Mederer was the kind of automotive hero the world needed. Wherever a rotary-equipped Mazda scorches along a backroad, there he is. He made them fly.