Media | Articles

The Caterham 7 JPE is a record-breaking blast from the past

In 1993, the now-defunct U.K. magazine Fast Lane was feeling pretty pleased with itself. “We Beat the World” read one of the headlines on the front cover of its May edition.

Beat the world it did. On Monday, March 8, 1993, Mark Hales, a respected journalist and racing driver, found himself strapped into a Caterham 7 JPE (Jonathan Palmer Evolution) lining up at the mile straight at Millbrook, a vehicle testing and development ground in Bedfordshire.

His job was to see if he could settle the revs of the 2.0-liter Vauxhall engine at just the right spot, play with the bite of the clutch and decide whether to slip it delicately or just drop it, brutally, like kicking a rugby ball to touch, then launch the latest Caterham 7 hell-for-leather off the line. There was no gear change to make, because first had been geared to run to 66 mph, and it was the run to 60 mph that Hales cared about.

In the end, after all manner of trial and error, nasty smells from the clutch, wincing from the passenger and chunks of rubber from the disintegrating Yokohama back tires, man and machine found a perfect harmony and the 7 surged off the line with every explosion of energy it could muster, setting a new Guinness World Record for the fastest-accelerating unmodified production car over the 0–60 mph benchmark.

The engine’s sweet spot turned out to be exactly 6250 rpm—no less, no more. Writing in Fast Lane, Hales described the brutal process. “Hold it for long enough to settle the engine and stop the needle flickering, but not so long that the clutch flutters and trips the timing gear. Then drop foot from pedal as if red hot. Throttle pedal bending against bulkhead. Revs stay constant around 7000 rpm, neither rising nor falling until about 55 mph when the forward speed catches up with the spinning wheels. JPE does a little waltz as revs dip a needle’s width, speed of wheel matches speed of car and I snatch second just in time to stop the limiter cutting in. And there it was.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“Silver record tape revealed a 3.44 second run to the North, and a 3.48 to the South. An average of 3.46 seconds. Under the current rules, the fastest-ever run from rest to 60 mph with an unmodified production car.”

The Caterham 7 JPE made a Ferrari F40 seem slow

That wasn’t the only achievement chalked up by Caterham’s wildest 7 to date. The year before, in October, Autocar & Motor subjected the JPE to its 0–100–0 Challenge. The record holder at the time was the Ferrari F40, which sprinted to 100 mph and screeched to a stop in 15.9 seconds. The JPE would smash that by nearly three seconds, with a time of 13.1. (You can watch the video below, to see Derek and Justin Bell performing a record attempt, with the team from Caterham.)

For little old Caterham, a company working from a glorified shed within spitting distance of the Dartford Crossing, to come along and leave trailing the mightiest car Maranello had to offer at the time, then claim a Guinness World Record, was impressive. However, it’s only when you look back through the Guinness records, and see which car captured the record from the 7 JPE, that appreciation for this underdog can truly sink in: It was the McLaren F1.

By now you can probably sense that the 7 JPE was out of the ordinary. It was born of a special time—a time when Caterham was owned and run a little like a hobby shop; a time when emissions legislation and single vehicle approval was yet to impact on the way small, independent manufacturers like Caterham developed sports cars; and a time when projections, forecasts and profit-and-loss accountability didn’t get in the way of good ideas.

Which is how I find myself standing in the showroom of Sevens & Classics, the largest independent dealer of Caterham 7s. Located a stone’s throw from Brands Hatch’s Paddock Hill Bend, it is run by Andy Noble, the former sales and marketing director for Caterham Cars.

Noble was the ideas man behind the 7 JPE, who worked in close partnership with Jez Coates, the former technical director for the company. They reported to Graham Nearn, the owner of the business, who, as a Lotus dealer, bought the rights to the Lotus 7 from Colin Chapman, in 1973.

Sevens & Classics has a 7 JPE for sale, a rare occurrence in the UK. Only 53 were built over the decade or so it was available, and around 10 are believed to be here, with the rest mostly exported to France and Japan. And happily, its generous owner, Matthew Stears, has agreed to let me drive it.

The history of Caterham’s wildest 7

Noble takes us back to the car’s gestation and laughs when asked whether there was a prolonged period of research and development for this, the most super of Sevens.

“It was a different environment. In those days we used to stay behind at work and mess around with cars and build stuff. We used to go racing and we’d work on a car till midnight, bolt it together, come in at six in the morning, stick it on a trailer and go racing, come back on Saturday night and just put it back in the workshop. There was no accounting for parts, there was no costing it, there was there was none of that; we just cracked on with it. And whilst that sounds scary in today’s climate, the company made a good profit and as long as Graham was happy we were left to crack on with it.”

Nearn, recalls Noble, rarely shared the accounts with those around him. So when Noble suggested the idea of creating both the most affordable, simple Seven yet, and the most extreme, high-performance derivative, there were no presentations, no development cost meetings and no need for sales forecasts. Nearn simply told Noble and Coates (they sound like a Caterham double act, and they really were) to go for it.

And they duly did. “It’s not like you got a business proposition, or, ‘Right, we’ve got to sell 40 of these to pay for development,’ because development was in a shed banging these things together. We bought in each engine, we bought in the gearbox, had the best tires, so it was just a case of putting it all together,” remembers Noble.

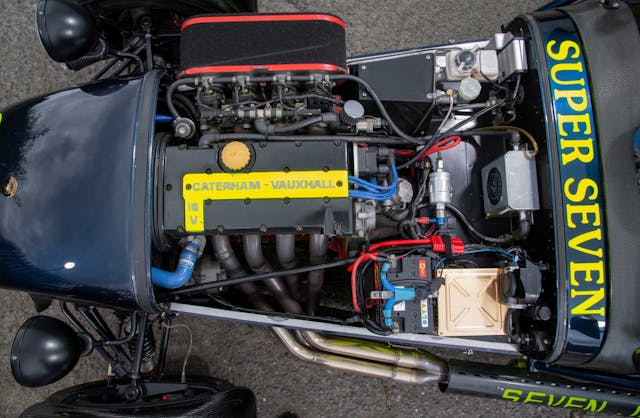

The choice of the Vauxhall engine was a natural extension of Caterham’s HPC model, at that point the fastest model in the range. It used the 2.0-liter Vauxhall twin-cam engine, in 175-hp spec. Caterham picked up the phone to Swindon Racing Engines, which built the motors that powered the likes of John Cleland in the his BTCC Vauxhall Cavalier GSi, and placed an order for the same motorsport engines. Each one is reputed to have cost roughly $23,400 (£13,000), partly explaining why a 7 JPE was so damned expensive—at nearly $60K (£34,950), twice the price of the next nearest model.

It was introduced at the 1992 British Motor Show. At the time, Graham Nearn told fans and media, “This car is not for the faint hearted and represents the best value for money in the supercar league table as it outperforms every other car in the sports car class for a fraction of the price. Jonathan Palmer has intimate knowledge of what we were looking to achieve with the car because of his F1 development, and world sports car racing experience. Caterham Cars is delighted to be involved with Jonathan Palmer on this exciting new car and we are pleased to announce that purchasers will have the opportunity to meet Jonathan, and assess their driving ability.”

Noble explains how the relationship with Palmer was established. Initially, Palmer approached Caterham about lending demonstration cars to support his fledgling PalmerSport driving experience business, which he launched in 1991 after walking away from Tyrell and Formula 1, at the end of ’89. He and Noble had previously met at a Ford corporate day, racing against one another on quad bikes, Palmer crashing off and later suggesting he had gifted the guest, Noble, the win. Ultimately the chance encounter laid the foundations for the JPE.

“There was no fee involved,” adds Noble, another reminder of how this is a car born of different times.

Today, Sevens & Classics is asking £51,995 ($65,254) for this JPE. If that strikes you as a lot of money for a Caterham, bear in mind that for those that grew up devouring motoring media, its sale represents a chance to own one of the highlight cars of the ’90s. S/n 19 of the 53 built, it’s a 1994 model that is said to have been bought new by the son of Peter Stringfellow. It was then sold to a gentleman in Jersey, before its current owner, Stears, snapped it up in 2015.

Now, I’ve driven and raced a fair number of Caterhams in my time, including various Superlights, the R400, R500, and 620R, but never a JPE. So this was too good an opportunity to miss.

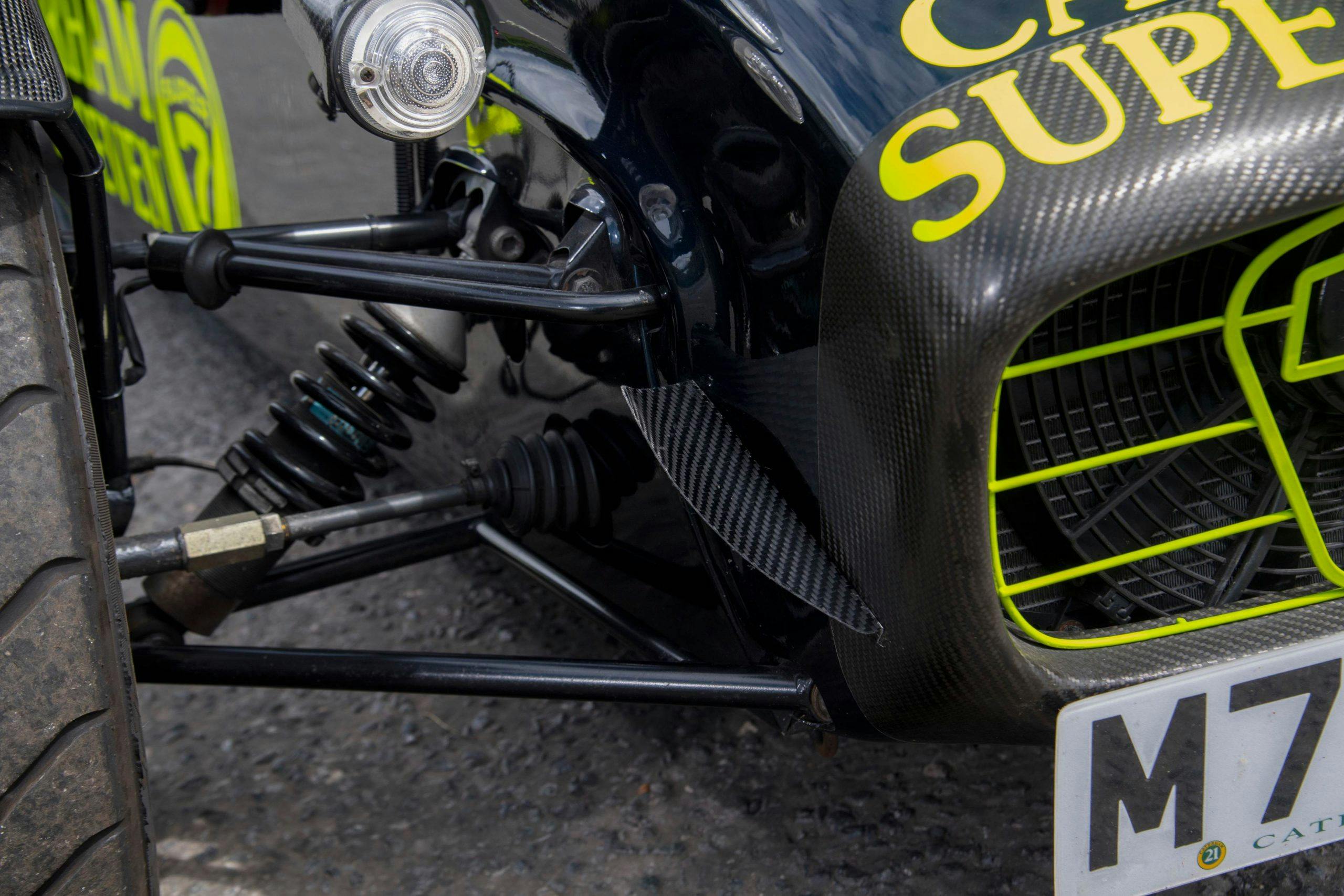

The geeks out there will be disappointed to see that the body is painted. Some cars weren’t, as Caterham suggested it shaved 4.4 pounds (2 kg) from the car’s 1168-pound (530-kg) curb weight. But it wears its signature exhaust with the heat shield stamped with “JPE” (note to Caterham: this should be a signature across the Caterham range) and the bright graphics on the bodywork are a tribute to a Tamiya model.

At some point a race-spec rollcage has been fitted, which adds some torsional stiffness to the chassis and, more significantly, enhances protection for occupants. And the gearbox is Caterham’s six-speed unit, an option offered on JPEs just as soon as Caterham launched it in the early ’90s. But other than that it’s entirely representative of the way the JPE drives.

With the battery isolator switch armed and ignition switched flicked, a red starter button brings the Vauxhall engine to life. There are no histrionics, just a clean, loud idle that burbles away as you fasten the Luke six-point harness and look around to take in the surroundings of the cockpit.

The fixed carbon-fiber Tillet seat isn’t the original version; they were lost during the car being shipped to the U.K., so later versions were added—a good thing, too, as the original chairs lacked a headrest. The rev counter features a green painted sweep between 6500 and 8000 rpm while the 150-mph speedo is marked with 10-mph increments, unlike the first car’s, which only started reading at 70 mph, causing something of a stir.

There’s a quick-release Momo steering wheel, engraved with the Jonathan Palmer Evolution name, and a plaque on the dashboard tells curious onlookers that s/n 19 was built by Gary May. (All JPEs were built by May, I’m told.) The dashboard is a slither of carbon-fiber and the instruments wear a fluorescent yellow background, while a set of shift lights is perched on top of the dashboard.

The pedals are a stretch, the clutch action is best described by Stears—“it’s digital”—and the throttle pedal’s action is delightfully precise—but you’ll need to brush your right foot deliberately against the aluminum panelling to steady yourself and avoid pogoing up the road like a learner driver.

Despite boasting featherweight Cosworth pistons, wild cams and a compression ratio of 12:1, and carrying a rather exotic looking set of inlet trumpets to channel air to the Cosworth-designed cylinder head, the first surprise is how tractable the engine is. The touring car specification lump had Weber Alpha fuel injection added to make it drivable, and it shows. It pulls eagerly from low in the rev range, with the only hesitation, ironically, just before all hell breaks loose at about 6500 rpm.

That hesitation is a feature of the engine’s design but you’d be forgiven for imagining someone, somewhere at Swindon Racing Engines, wanted to give the driver the chance to opt out and ease off the power before entering warp speed.

When it goes, it flies. The engine spins up to the red line with an energy and enthusiasm that is entirely absent from modern motors, surging hungrily for the rev limit and forcing the 7 JPE through the air so violently that your ear drums flex from the resonance. You grimace, involuntarily, grab another gear, grimace some more, then find your face breaking into a smile as you start to appreciate that this is so much more than a 7 with a hot engine.

The rest of the package has been beautifully resolved. The JPE rides the road with a surprising suppleness. It doesn’t hop or skip like some Caterhams. Instead, its suspension keeps the wheels in just enough contact with the road surface so that, when the full 250 hp reaches the back wheels, the rear performs just the gentlest of squirms that you can ride out in confidence. All the while, the messaging through the steering and the seat of your pants is exquisite.

The wide-track, double-wishbone front suspension gives the car a planted feeling and the brakes, fitted with an uprated motorsport servo and four-piston alloy calipers offer wonderful bite at the top of the pedal travel and drag speeds down to sane levels in no time at all. Little wonder it managed the 0–100–0 mph challenge in just 13.1 seconds.

It is a consuming, thrilling experience. And the surprise that comes with miles under the belt is that the JPE’s driving experience isn’t intimidating—isn’t dominated by the engine or found to be only fit for the drag strip at Santa Pod. This is a well-resolved car which has so much more to offer than straight-line speed.

But then we already knew that. For a while, the JPE was on top of the world. And even after 28 years, it still feels like a record breaker.

With thanks to Matthew Stears. Contact Sevens & Classics for further information about the Caterham 7 JPE that’s for sale. Via Hagerty U.K.