Media | Articles

Fordite: A Motor City gemstone

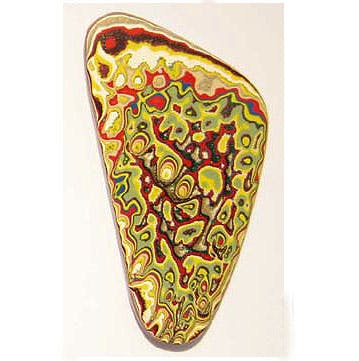

Rock hounds flock to the shores of Lake Superior in search of agates, the colorful layered gemstones treasured by lapidaries and lovers of semiprecious stones. Those agates were formed with layers of different minerals eons ago when water vapor, carbon dioxide, and silica became trapped in iron-rich lava flows. Lapidaries today also work with another form of “agate,” one that’s decades rather than eons old, created just a few hundred miles south of “the big lake they call gitche gumee,” in the words of Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot. Some call this variegated stone “motor agate,” industrial agate, or Detroit agate, but its more popular name is fordite. Unlike real agate, it was created in car factories, not volcanoes.

The way that cars and trucks are painted in modern assembly plants is vastly different than the process used a half-century ago, both in terms of the paint chemistries and application technologies. Government regulations on volatile organic compounds introduced in the 1980s resulted in the introduction of water-borne color coats and two-part, self-curing polyurethane clearcoats that were applied electrostatically, with little overspray. Before then, much automotive paint was solvent-borne acrylic or alkyd enamel. These substances were applied with pressure sprayers in downdraft spray booths and then oven-baked to cure and harden them. The racks, skids, and conveyor equipment carrying the car bodies got covered with overspray and were baked along with the car bodies. Over time, that overspray would accumulate and the “enamel slag” would have to be removed. By then, the slag would be a rock-hard, multilayered mass of acrylic, each layer a different color.

Most of the colorful substance was discarded as waste, but one day, someone figured out that the accumulated acrylic could be ground and polished to produce beautiful, almost psychedelic cabochons and set into silver rings, cufflinks, necklaces, and other pieces of jewelry. (In contrast to a precious stone that’s faceted, a cabochon is simply polished. A cabochon is the typical cut for a semi-precious stone and most have a rounded cross-section.)

That’s how the raw material was made. Exactly who figured out that the chunks of synthetic “rock” could be tumbled and polished like actual gemstones is uncertain. I’d put my money on an amateur lapidary who worked either on an assembly line spraying cars or on a cleanup crew, stripping the overspray. Whether or not the repurposing occurred at a Ford factory is also unclear. You can, however, buy fordite created at Ford factories as well as Harley Davidson fordite,” apparently salvaged from a motorcycle factory, and Kenworth fordite, collected from a plant that makes heavy-duty trucks.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Like genuine semiprecious stones, the material is actually rare. Since both the substance and process of painting vehicles have since changed, there’s a limited stock of authentic fordite and, unlike its naturally-occuring counterparts, you can’t just comb a beach for it. The most valuable motor city agate dates to the late 1960s and early 1970s, the period of so-called “high impact” colors like Ford’s Grabber Blue or Mopar’s Plum Crazy purple.

Perhaps the preeminent promoter of fordite is Cindy Dempsey, an independent jewelry maker and artist and the owner of Urban Relic Design. Based in her home state of Illinois, she’s been working with the material for more than twenty years and may well be responsible for naming it fordite. (Fordite.com, founded by Dempsey, makes it clear that the substance’s name “in no way implies any relation to The Ford Motor Company,” and that neither Dempsey nor the site is affiliated with the Ford or any of its subsidiaries.) Dempsey first encountered industrial agate as an artistically inclined youth in the 1970s.

“I came across my first pieces of this material in the mid 70’s, when I was young,” she writes. “A friend of the family worked in the car manufacturing business, and he brought a few chunks of this clumpy, hardened paint material over to the house. He called it ‘paintrock.’”

Dempsey later developed an interest in mineralogy and gemstones in school. Among her favorite stones were malachite, a copper-rich mineral that displays ripples of jungle-green shades, and spectrolite, an uncommon variety of labradorite, characterized by particularly vibrant streaks of iridescent colors. With her taste for unusual and vibrant colors established, Dempsey was naturally fascinated by “paintrock,” which she renamed fordite.

“These chunks didn’t look like much more than globs of cured paint,” she continues, “but when you sanded through the surface layer, they really looked organic underneath, like gemstones, with the same kinds of stripes and concentric rings, just like real banded agates! And the colors had all these metallics! Wow! It was really cool …”

She made some small items from the material and sold the jewelry to family friends.

Later on, Dempsey became an artist—first a painter and then a metalsmith and designer of fine jewelry. She consistently repurposed and upcycled various metals and minerals, and eventually she returned to fordite, determined to process the factory-amalgamated substance to its best advantage.

“I eventually fell into my next big stash of fordite rough and really learned to cut and polish it finely. I cut bunches of cabochons and shared them with other jewelers to spread the word! I then spent years talking to people, hunting down old-timers who had collected it, and gathered fordite wherever I could.”

As with actual minerals and gemstones, fordite has its own taxonomy. Dempsey lists four main categories:

Type 1: Separated colors — Regular grey banding of primer layers between color layers.

Type 2: Color on color — Opaques and metallics. Limited colors. Small parts and special color runs.

Type 3: Color on color — Drippy and/or striped, with multiple color on color layers with metallics. Sometimes containing lace and orbital patterns, with occasional surface channeling.

Type 4: Color on color — Opaques and metallics, with bleeding color layers, sometimes containing pitting from air bubbles as the layers formed and hardened.

Dempsey sells her finished jewelry at fordite.com. She tried to trademark the term, but Ford Motor Company’s lawyers objected; however, FoMoCo hasn’t hassled her about the domain name so far. Instead, Dempsey has registered Motor Agate with the Trademark Office.

She’s not the only one selling fordite, so while it’s rare, it’s not exactly unobtanium. A number of vendors on both eBay and Etsy sell fordite either as raw material or as finished stones and jewelry.

It is, however, rare enough to be counterfeited. Karla Piper, who sells fordite jewelry and accessories at Silver Siesta Jewelry, warns about “fabricated fordite.”

Besides buying it from Piper or Dempsey, you can also get fordite jewelry, appropriately, at the Henry Ford Museum Gift Shop when it reopens to the public. Interestingly, while you can buy it in the museum’s gift shop, you won’t find ford in the museum itself. When we spoke to Matt Anderson, the museum’s automotive curator, about the history of fordite, he told us: “You know, we probably should have some in the collection.”

What do you think?

I remember touring the Ford plant in the late ‘60s. The tour guide gave all us kids a multi-colored layered paint chip. Wish I still had it.

For a long time, Asians have been using purposefully accumulated colored lacquer–allowing it to dry, then cutting it into shapes, then polishing it into jewelry. I have some right here in the room with me. So, this is not a new technique.

I had never heard of it until my daughter gave me a piece for Christmas. I thought that was one of the coolest things I had ever seen. It’s one of the best gifts I had ever received. It proudly sits on a little display in my office.

My wife would find it all very pretty.