Media | Articles

Where the first automotive roadmaps came from

Thanks to Smartphone apps such as Scout or Google Maps, or in-dash GPS navigation systems, drivers rarely get lost anymore. But it was once a far more common occasion. And the solution? A folded paper roadmap. And if you think modern navigation systems are unreliable, imagine relying on your passenger’s ability to read a map accurately, never mind refolding it correctly.

Mapping beginnings

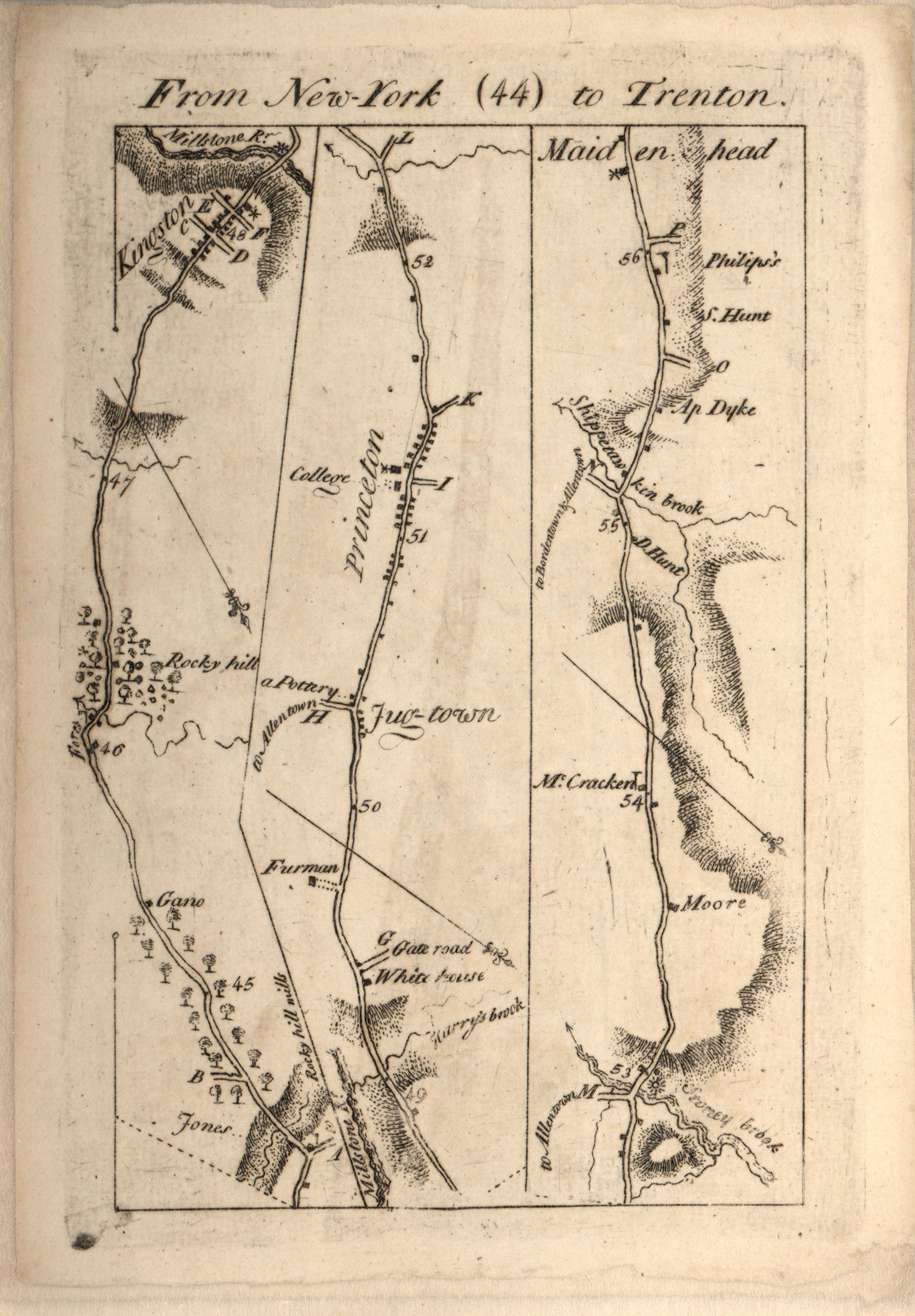

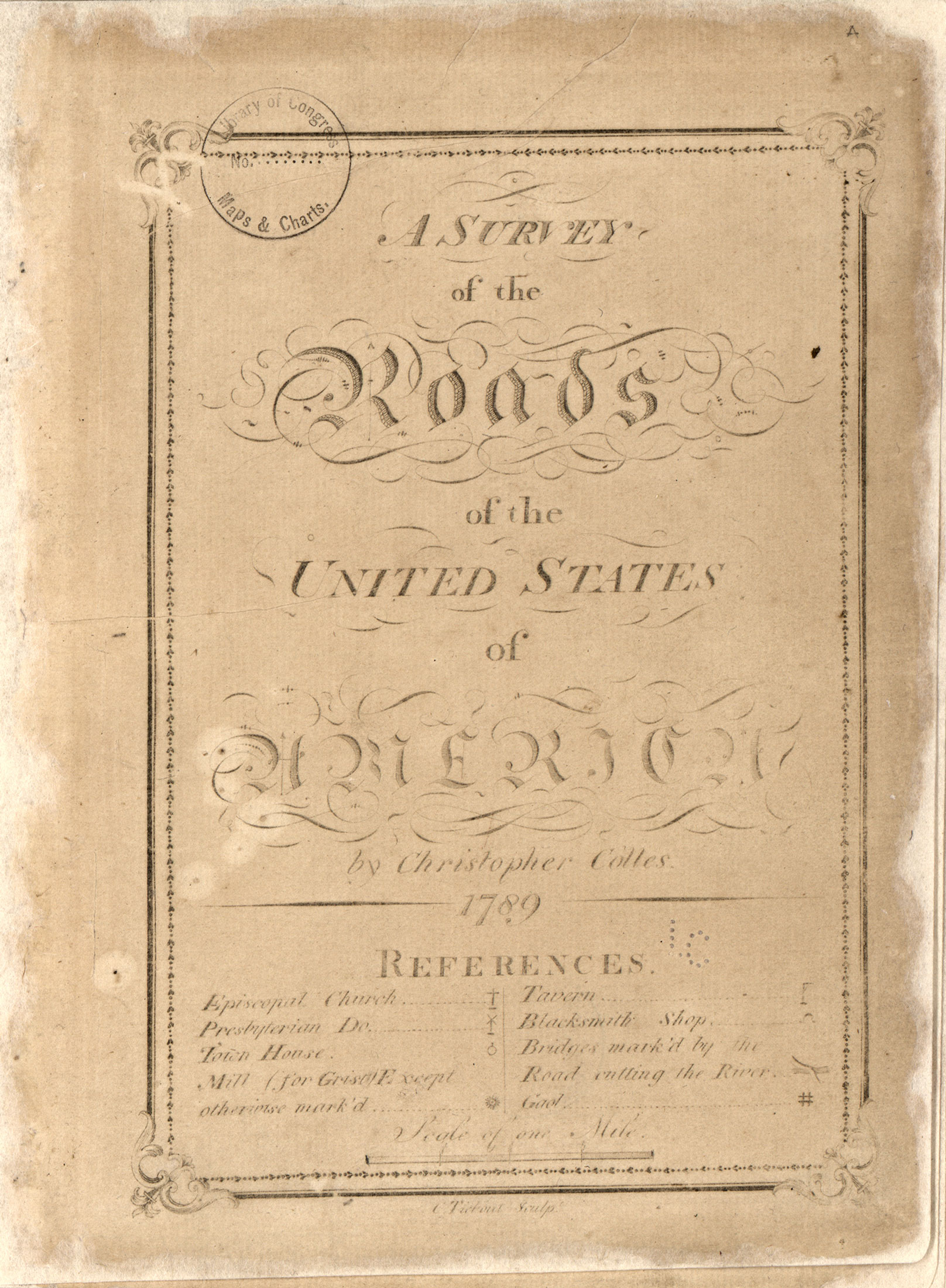

Maps of America’s biggest cities date to the 18th century, as does the first successful road atlas, “The Survey of the Roads of the United States of America,” printed by Christopher Colles of New York in 1789. The company printed 83 plates over three years, with two or three maps on each plate. The guide ran from Williamsburg, Virginia to Albany, New York. It was subscription-based, with subscribers expected to bind the different plates together into an atlas.

Despite such distinguished customers as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, the effort faltered because there was little use for road maps in the United States. Most trips were short, made by locals who already knew where they were going. And besides, inner-cities roads were paved. Venturing any farther meant traversing unpaved, unmarked roads. Federal highways didn’t exist. Finding your way took time, patience and luck since most roads were originally trails carved out by wild animals or Native Americans.

It’s little wonder that until the early 20th century, travelling between cities was done mostly by rail, not by carriage. In fact, Rand McNally’s first map, printed in 1872, was a railroad guide.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Turn of the 20th century

The first truly useful motorist aid arrived in 1901, “The Official Automobile Blue Book,” which may sound familiar, but is unrelated to the modern-day Kelley Blue Book. Covering Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and Baltimore, the Blue Book was the work of Charles Howard Gillette, a prominent Hartford, Conn. businessman who established the Columbia Lubricants Co. to provide automotive oil and lubricants. He was also a car guy, serving as secretary of the American Automobile Association (AAA), and an occasional official starter for the Vanderbilt Cup automobile races.

While the book contained generalized maps, it didn’t contain complete maps of every road. Instead, there was a list of instructions guiding drivers from one place to another using mileage between towns, mileage between each instruction and local landmarks. It might say at mile 58.5, “left-hand turn just before railroad,” or “turn right away from poles.” The book included stops where drivers could find gasoline and lubricants, charge their electric vehicles, or find a repair shop.

The guide’s popularity increased significantly in 1906, when AAA became its official sponsor, and expanded to 10 volumes covering most of the country the following year.

But the guide had its competitors.

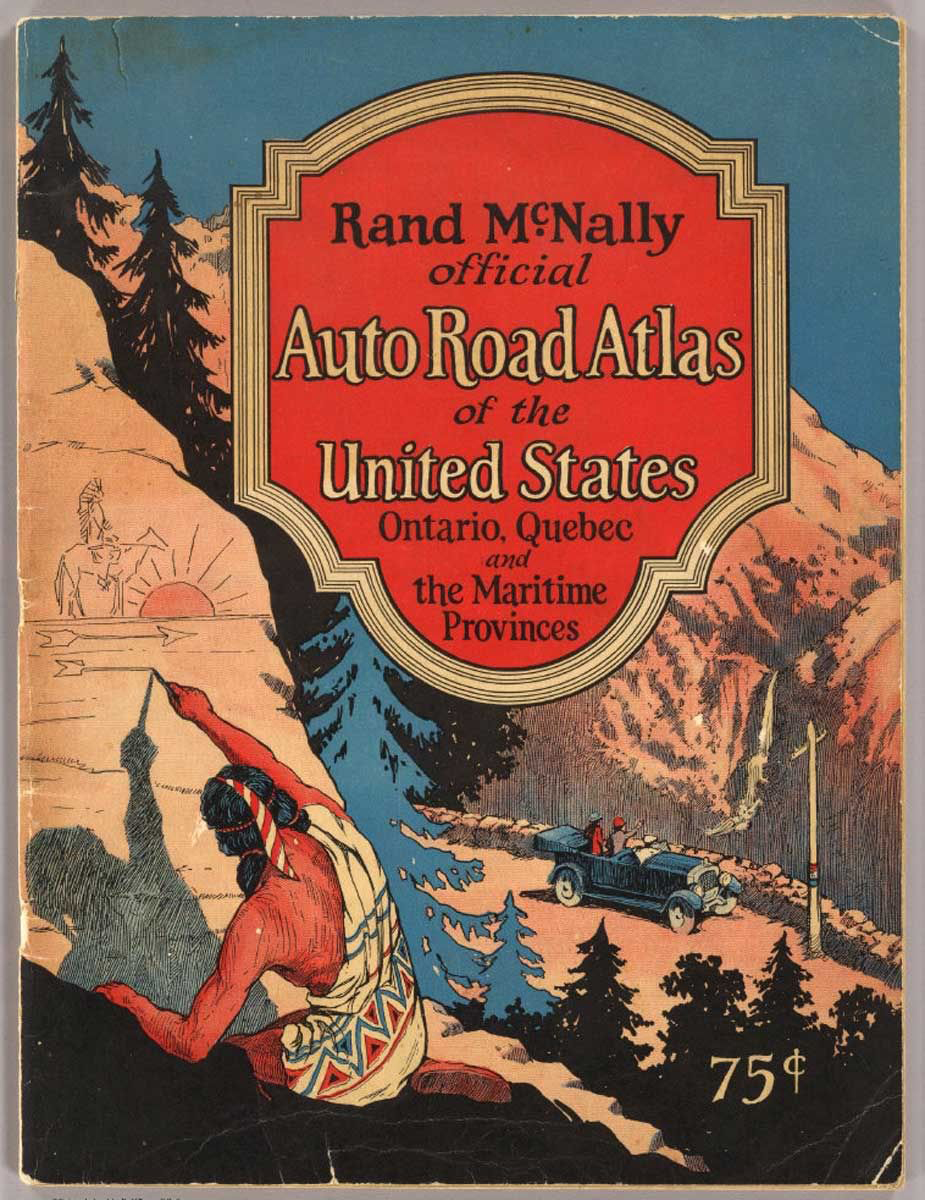

In 1904, mapmaker Rand McNally had printed its first automobile road map, “New Automobile Road Map of New York City & Vicinity.” Three years later, the company undertook publication of the Photo-Auto Guides from Gardner Chapin. The guide combined maps and photos with arrows to indicate turns. There was also Thomas Bros. Maps, established in 1915 in Oakland, California, by cartographer George Coupland Thomas and his two brothers. Thomas developed a unique page-by-page grid system of mapping that eliminated the need for a folding map. McNally loved it. By 1924, Rand McNally’s Auto Chum appears, the first edition of what becomes Rand McNally Road Atlas.

While these guide books were essential, they were soon joined by something new: the oil company paper road map. The first ones are attributed to Gulf Oil, which was formed by Pittsburgh’s Mellon family in 1901 to exploit Texas oil discoveries. In 1913, Gulf opened the first drive-in gas station in Pittsburgh’s east end and began handing out free road maps. Within a decade, most major oil companies had some form of promotional map program.

The Highway Act plots a path for the future

As road maps and guidebooks proliferated, Congress passed The Federal Highway Act of 1921, the single most important piece of legislation in the creation of national roads. Until its passage, America had no plan for roadbuilding. Under the new law, states would plan highways, and the federal government would manage design, construction, and stipulate maintenance standards. When finished in 1923, the new system totaled 168,881 miles, about 5.9 percent of all roads. Yet they reached 90 percent of the nation’s population. Principal highways had one- or two-digit numbers. Spur roads used a three-digit number that connected to the main highway. Important east-west routes had numbers ending in zero, while prominent north-south highways would end in 1.

Rand McNally was among the first mapmakers to incorporate the new system into its maps, which made travel easier (ability of the map reader notwithstanding).

As for roadmaps, oil companies continued issuing maps as marketing devices until the oil embargoes the 1970s, after which they lost interest in this form of self-promotion. These days, state governments print road maps, although Rand McNally still publishes its Road Atlas, a modern day descendent of the first road guides.

And even if you think your car’s navigation system, Google Maps, or your fellow passenger sometimes get directions wrong, keep in mind that paper maps intentionally contain mistakes, known as “map traps.” They are planted by mapmakers to prove copyright infringement when their maps get copied—most likely by GPS map providers.

So be kind to your fellow passengers the next time you get lost, and remember how far we’ve come from 18th century city maps.