Media | Articles

BMW’s racing history begins with the illustrious 328 roadster

“Ah, the spoils of war,” Andrew Mitchell says, revving the engine of a BMW 328 as it gently warms, rasping and clattering in the early autumn sunshine.

Less anyone has any doubts, this car is where BMW’s motorsports history begins. It’s where the company learned to win races through pluck and engineering, with the appliance of technology, modern designs, and materials, and wrapped it all in a terrific-looking body.

Engineered by men like Ernst Loof and Alex von Falkenhausen (the father of BMW motorsport) and designed by a team that included Fritz Fiedler and Peter Szymanowski (who went on to head up BMW’s design department), this was a car from the premier cru of the pre-World War II motor industry. It’s a measure of the car’s quality that after WWII, representatives of the Bristol Aeroplane Company took one of the Mille Miglia 328 models, along with technical details from the bombed factory, and (along with Fritz Fiedler) returned to England to design and build the heavily 328-influenced Bristol 400 as well as supplying Frazer Nash with engines.

“The BMW 328 is more than just the legend of the past, it is the BMW legend,” writes Bernd Pischetrieder, former BMW chairman, in the foreword to Rainer Simons’ encyclopedic BMW 328 From Roadster To Legend.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Yet the car in front of me looks surprisingly vintage and quite hard to link with the glorious written history of BMW’s first sports car. Even Halwart Schrader, in his book BMW: A History, didn’t think it the most auspicious motor. “This new two seater didn’t really look the part of a racer,” he wrote. “Just a nice civilized, handsome roadster.”

Certainly there are subtle hints outside—the faired-in wings, the tiny sills, the lack of door handles, and the streamlined body. Schrader, however, looked beneath the skin. “The real revolution here was under the sleek and advanced body shell.”

Before we get to examine the veracity of Schrader’s claim, however, Mitchell has stepped past the restrictive A post and into the snug-fitting cockpit, gunned the tight and technical sounding motor, engaged first, and torn off into the Wiltshire Downs. Jumping Jehoshaphat, this car can shift.

BMW 328 origins

The 328 was conceived in the 1930s at a time when barely one percent of all Germans owned a car. German carmakers had been knocked every which way by the economic crisis; DKW, Audi, Horch, and Wanderer had formed Auto Union, NSU pulled out of the car market entirely and lots of other car makers were wound up. BMW had profited from the boom in motorcycling, providing high-quality, shaft-drive machines at the top of the market. Most motorcycle owners, however, dreamed of owning a car, and from 1929 BMW tapped into that sentiment. BMW took over the carmaker Dixi and produced the Dixi 3/15, an Austin Seven built under licence.

Simons reckons it was the growing popularity of motorsport in Germany and an eagerness to compete amongst BMW’s engineers which prompted the swift move into sports cars. From January 1933, when Hitler’s Nazi party came to power, the state sponsored and encouraged motorsport through the National Socialist Driver’s Corps (NSKK) under Adolf Hühnlein. But even before that BMW had exploited Dixi’s sporting past by competing in events, such as the International Alpine Trials and Monte Carlo Rally, with converted Dixi models similar to the Austin Seven Ulster and badged as Wartburgs.

The 328, which was based on the early 315 and 319 models, debuted in 1936, the year of the infamous Berlin Olympics and the start of the Spanish Civil War. The 328 missed the Berlin Car and Motorcycle Exhibition and was only ready at the end of April, when it was shown at the Eifel Trophy Race at the Nürburgring. The production 328 didn’t go on sale until 1937.

BMW 328 engine and chassis

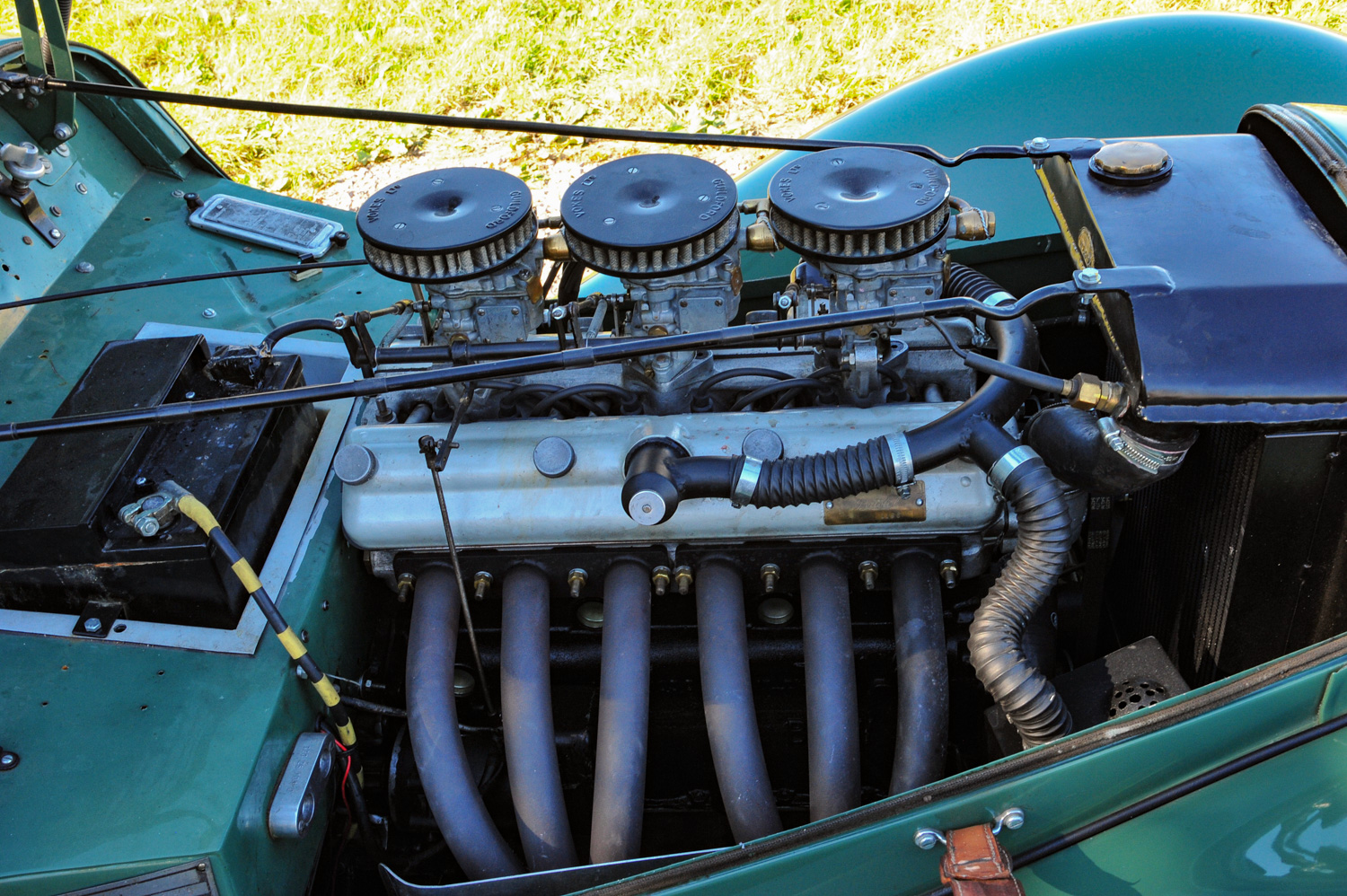

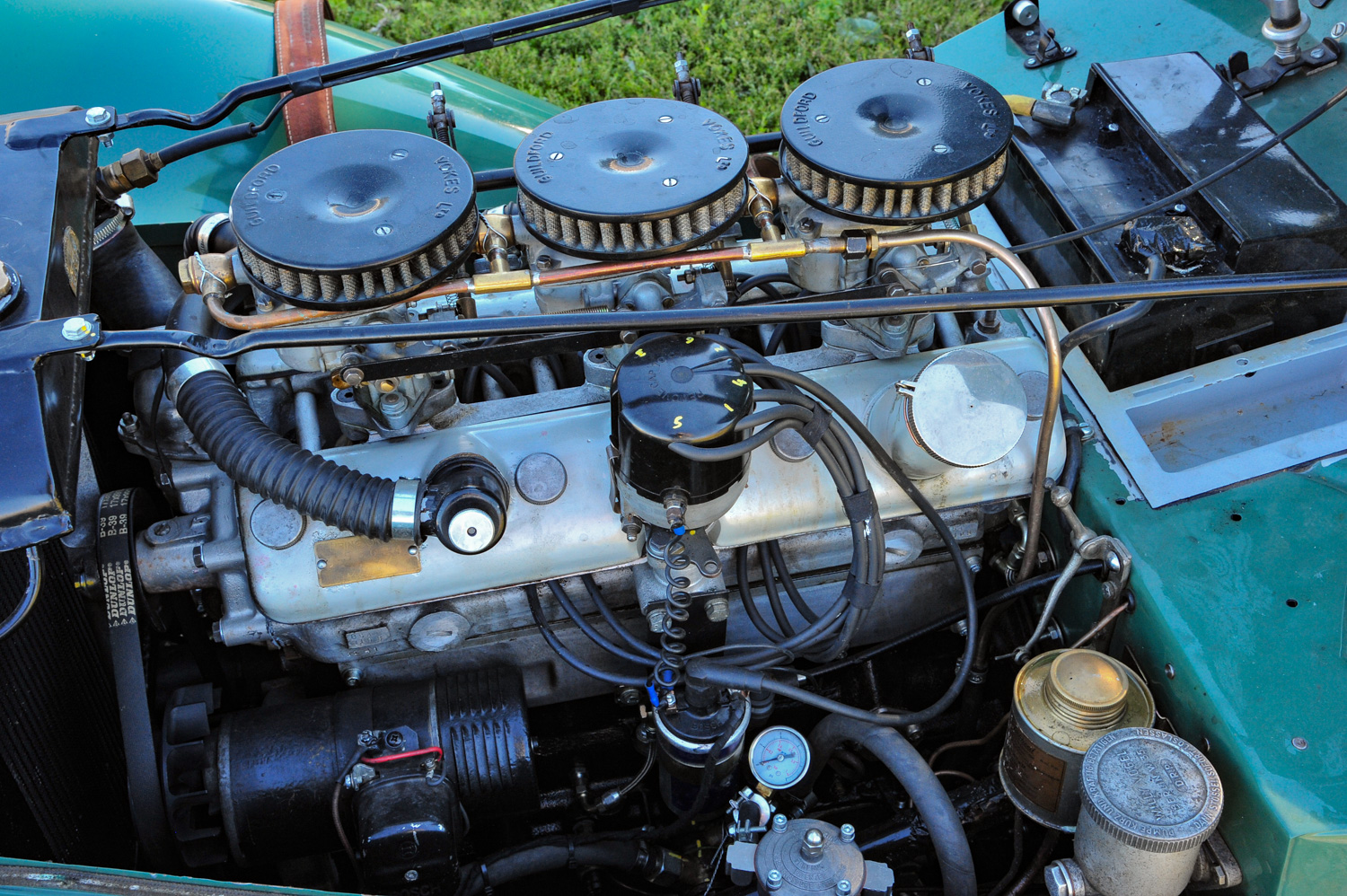

Its six-cylinder engine was inspired by a competition held by BMW MD Franz Joseph Popp, which was won by a stiff, advanced, but economical-to-produce idea from chief engineer Rudolf Schleicher. He worked with another Rudolf (Flemming) on the peculiar but undoubtedly effective six-cylinder, which used side-mounted camshaft operating the inclined valves in an aluminium hemispherical cylinder head via a series of knitting-needle-sized pushrod and rockers; the patent was awarded in 1939.

The 1971-cc cast-iron block came from the BMW 319 with the camshaft driven by double roller chain. The vanadium steel crank ran in four main bearings initially white metal but soon changed for shell bearings, with lubrication from a large capacity gear-driven oil pump. With a 66-mm/96-mm bore and stroke and a 7.5:1 compression ratio, the engine breathed through three downdraught Solex Type 30 JF carburettors fitted with wire mesh filters. Maximum power was given at 80 hp at 4500 rpm, although even back then the competition department was getting an additional 10 hp. These days, these engines comfortably produce in excess of twice that.

So it’s a decent enough engine, which despite its long stroke and bendy valve gear had lots of potential for tuning, driving the rear wheels via a four-speed transmission. But what about the body? That was an all-aluminium, swept-back two-seater with a tall, two-piece flat windscreen. The spare wheel faired into the rear, except for the first prototype cars, which dispensed with that arrangement. This was a no-frills design; lightweight, with twin bonnet straps for the rear-hinged bonnet as required of international racing regulations. It was 153.5 inches (12.8 feet) long, 61 inches (5 feet) wide, and 55.1 inches (4.6 feet) tall, running on a 94.5-inch wheelbase. It weighed just 1830 pounds, which perhaps explains a little about the performance.

The chassis was a rigid ladder frame with fabricated side tubes and box-section cross members. Front suspension was a swing-axle layout with an upper transverse leaf spring and lower A frames. Rear suspension was a leaf-sprung solid rear axle with hydraulic dampers all round. Wheels were quick-release discs and there were hydraulic drum brakes all round. Launch costs were modest, about RM445,000 which was less than a third for that of the BMW 320.

Light, powerful, and with a deceptively modern construction, I’m beginning to see what folk saw in this car. Confirming this is my ongoing struggle to keep up with Mitchell in this shed-green 328 as he romps across the Downs. True this particular 328 is hepped up in racing trim (it appeared at this year’s Le Mans Classic and won its class) and Mitchell who raced it, so he not only knows the roads, but also this car.

Racing pedigree

In fact, the 328’s motorsport credentials were established right from the start. After Henne’s victory at the 1936 Nürburgring, there was the 1000km at Montlhéry in France, where BMW entered all its prototype racers, including one British Racing Green right-hand-drive car (#85003). This had been built for its British agent AFN and it was entered as a “Frazer Nash – BMW” and driven by Harold (HJ) Aldington and Alfred (AFP) Fane. The rigours of high-speed running on the concrete banking proved too much, however, and all three retired.

Aldington drove a 328 to victory in its next race in Munich, and in September the works cars were entered in the Tourist Trophy at the Ards circuit in Ulster, where in #85003 Fane won his class and came third overall. It was entered into the Shelsley Walsh hillclimb the following week, when Fane drove it up in a commendable 49.1 seconds. After a glittering career in the UK, Aldington took #85003 to Hamburg on the eve of WWII to compete in the city’s park races. After an accident it was sent to Munich for repairs and remained there for the duration of the war. Whether that car still exists is the source of some debate in BMW circles.

The 328 had 100 class wins in 1937 including the Tourist Trophy and La Turbie hillclimb. In 1938 it won its class in the RAC Tourist Trophy, the Alpine Rally, and the Mille Miglia, and the following year it won the RAC Rally and was first in its class (and fifth overall) at the 24 hours of Le Mans.

Behind the wheel of the BMW 328

We finally catch Mitchell and I take the wheel. My well-padded post-war frame makes it a struggle to get in, but once ensconced behind the big black wheel it’s quite comfortable and the addition of a couple of hip supports fitted for classic Le Mans hold you firmly. The gearbox slots through a conventional H pattern and is surprisingly free of temperament and it’s the same with the light and direct clutch, so with a snarl of the exhaust, we’re off.

On the move the ride is a revelation. Even on racing suspension the old car rides beautifully, coping with the occasional pothole without the body shimmying much. In fact, the frame feels as taut as a racing dinghy and the overall impression is of sailing this lovely car along a ribbon of pavement. The steering is deceptively direct, but you don’t so much steer as think the nose round corners, there’s such a connection between driver and car that it’s hard not to put your foot down and exploit it.

When you do, the engine’s rasping wail is valiant and true, and while the gearbox could do with an extra ratio, it feels quick even by modern standards. I’m not absolutely sure how far north of 5500 rpm I’m supposed to be exploring, but I hang on to third up a long hill and the old BMW races up the ascent as though it’s flying into the stars. At the top, we’re going so fast I need a bit of a confidence lift to negotiate the next turn. While the top speed isn’t much above 100 mph, it’s the way you can maintain speed in this car which is so charming.

“These were massively advanced machines,especially when you compare them to pre-WWII rivals,” says my friend Peter Haynes, a journalist and PR man who drove and raced his father’s famous 328. “The brakes work, the steering is light and precise, and it goes well too. In fact, it feels like a post-war car, and I’d go so far as to say it’s better than some post-war cars.”

A million-dollar charmer

Of the 464 built, only about 200 of the 328s are known to exist, although another turns up from time to time. And the car’s influence spread far and wide. As well as the Bristol and Frazer Nash connection, the body style is recognizable in cars such as the Jaguar XK120, Pinifarina’s Alfa Romeo 6C2500 SS, and perhaps even the Austin Healey 100. The engine was used in Tojeiro and Neumaier specials and the Cooper Bristol Formula 2 car, which provided a fair bit of the tuning expertise found in today’s engines. It was also used in AC cars, the Ace and Aceca, and after WWII the 1949 Veritas claimed to be the true heir to the 328—although this was fiercely contested by the Aldington brothers of Frazer Nash.

Even today a decent 328 will cost in the region of a $1 million, more if it has special history. Watch out for the Sbarro-designed replicas done in the 1970s, which are lovely in their own right but not the same thing at all.

And despite approaching this car in the most skeptical frame of mind, I have to admit it’s a bit of a charmer. As Mitchell says, “You could go a long way in a day in this car.” After an all-too short drive in this 328, perhaps the highest praise is to say I’d like to give that claim a try.

I bought my 328 in Frankfurt in June 1952 drove to LeMans, then NY to SF prior to discharge. I raced in the early 50s and found a Weinberger bodied Cabrio to use while prepping my “racer”. I never paid more tha $1250 for a328 ! James Smith ended up with the Cabrio and another “bitsa” I had bought for its drilled wheels. Great memories