Media | Articles

The other lasting legacy of the Chevrolet Corvair

General Motors is a favorite punching bag for futurists and stockholders alike. Both parties share disappointment in what’s perceived as a lack of motivation for bringing innovative automotive technologies to the market. While the past few years may have shaken off much of that accumulated baggage—witness the Bolt, the Volt, and a magnetic suspension system so good it’s been licensed by Ferrari—it’s true that the General hasn’t always been willing to bridge the gap between the lab and the street.

This wasn’t always the case, of course. For much of its early existence, GM pushed forward as hard as it could towards the automotive horizon, innovating on a near-constant basis in a bid to outperform the competition. The fact that in the early 1960s, one of its most forward-looking vehicles—the Chevrolet Corvair—also led to one of its most crushing defeats, both on the market and in the minds of buyers, played no small role in stamping down the desire to take risks for much of the next quarter-century.

Had the Corvair not become synonymous with safety-crusader Ralph Nader’s campaign to fix what was an admittedly broken industry at the time, it could have pointed towards a very different future for General Motors. What might that untold story look like had the tide of public opinion flowed in the other direction?

Yes, it was dangerous

It’s best to get the inconvenient truth of the Corvair out of the way as quickly as possible: yes, the rear suspension design on the 1960–63 versions was not well-matched to the task of carrying the weight of the engine that was located just behind it. The swing-axle design required front tire pressures to be kept at nearly half the psi of the rears in order to avoid snap oversteer—something Chevrolet communicated poorly to its salespeople and customers. That low tire pressure—15 psi cold—would also often cause the rubber to break from the wheel bead and spontaneously deflate. Add those two serious flaws, plus the lack of a front swaybar to control body roll in corners, and you have a recipe for well over 100 accident lawsuits in a very short time period (and a full chapter of Ralph Nader’s iconic Unsafe at Any Speed being devoted to the car).

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Chevrolet would install a much better four-link setup (and make a front swaybar available) when the car was redesigned for 1965, but the damage had already been done in the court of public opinion. These much safer models never got a fair shake, and Corvair sales fell by an astonishing 96 percent by the end of the decade, when the model was finally discontinued.

That the Corvair would suffer such an ignominious end is a legitimate tragedy, because it undoubtedly changed the trajectory of GM’s product development towards the risk-averse culture that would dominate throughout the 1970s and ’80s. Much of the promise held by Chevy’s unique offering was wiped off the board in one fell swoop, depriving domestic car fans of a number of promising developments that they would have to wait (and wait… and wait) to see again.

Innovation in the trunk

The genesis of the Corvair was a simple one. Imports were just starting to attract the attention of curious and economy-minded drivers in the late 1950s, with the Volkswagen Beetle the most conspicuous member of this cheap-to-own, cheap-to-drive brigade. Whereas many of America’s automakers were content to simply chop their intermediate platforms by 20 percent and offer a six-cylinder engine, General Motors saw an opportunity to not just introduce a fresh small car platform but also experiment with a number of high tech ideas in the process.

To wit: Chevrolet took the Beetle at nearly face value and decided that if Germany could build an affordable, rear-engine, air-cooled automobile, then so could Detroit. To this point, only VW, Porsche, Fiat, and Citroën and Tatra had mass-produced air-cooled anything, so GM was going out on a limb in trusting American buyers would be comfortable not only with a breeze-based engine, but one that was placed in the trunk.

Just a couple of years after it debuted, Chevrolet pushed things even further forward by way of the turbocharged Corsa engine. Eventually delivering more than double the horsepower of the original, economy-oriented six (180 horses from 164 cubic inches on later Corsa cars, 150 horses for the early Spyders), the design featured a draw-through turbo that placed the carb just ahead of it in the air stream.

This made the Corvair—after the Oldsmobile F85, which appeared just prior—the second turbocharged car offered in America. It was quick, it was reliable, and when it left the line-up in ’66 it was doomed to be the last compact that GM would outfit with forced induction until the 1980s, when the Pontiac Sunbird would once again take up the turbo mantle among entry-level automobiles.

Chevy also had some way-out-there ideas for the flat-six, overhead valve engine offered in the Corvair that would percolate behind the scenes throughout much of its original run. One of the most intriguing was the idea of a modular design that could be deployed in two- to 10-cylinder arrangements (with the latter eventually finding its way into a concept front-wheel drive ’62 Impala, informing the eventual development of the Oldsmobile Toronado).

Although the modular engine idea was viewed as profitable when the Corvair was selling 1.7 million units in its first three years, by the middle of the decade GM realized it had no other rear-engine (or front-wheel drive) vehicles to spread out development and tooling costs for the engine, rendering the concept stillborn. The company’s Tonawanda aluminum foundry—which existed largely to furnish cylinder heads for the Corvair—would be kept online until 1983.

All in the family

Although it would prove problematic—at least until it was replaced with a four-link setup similar to that offered by the Chevrolet Corvette—the Corvair’s suspension was the first fully-independent offering from GM. This ground-breaking achievement for the company was especially notable given that Chevy beat Cadillac to the punch, and did so in one of the cheapest models available in the showroom.

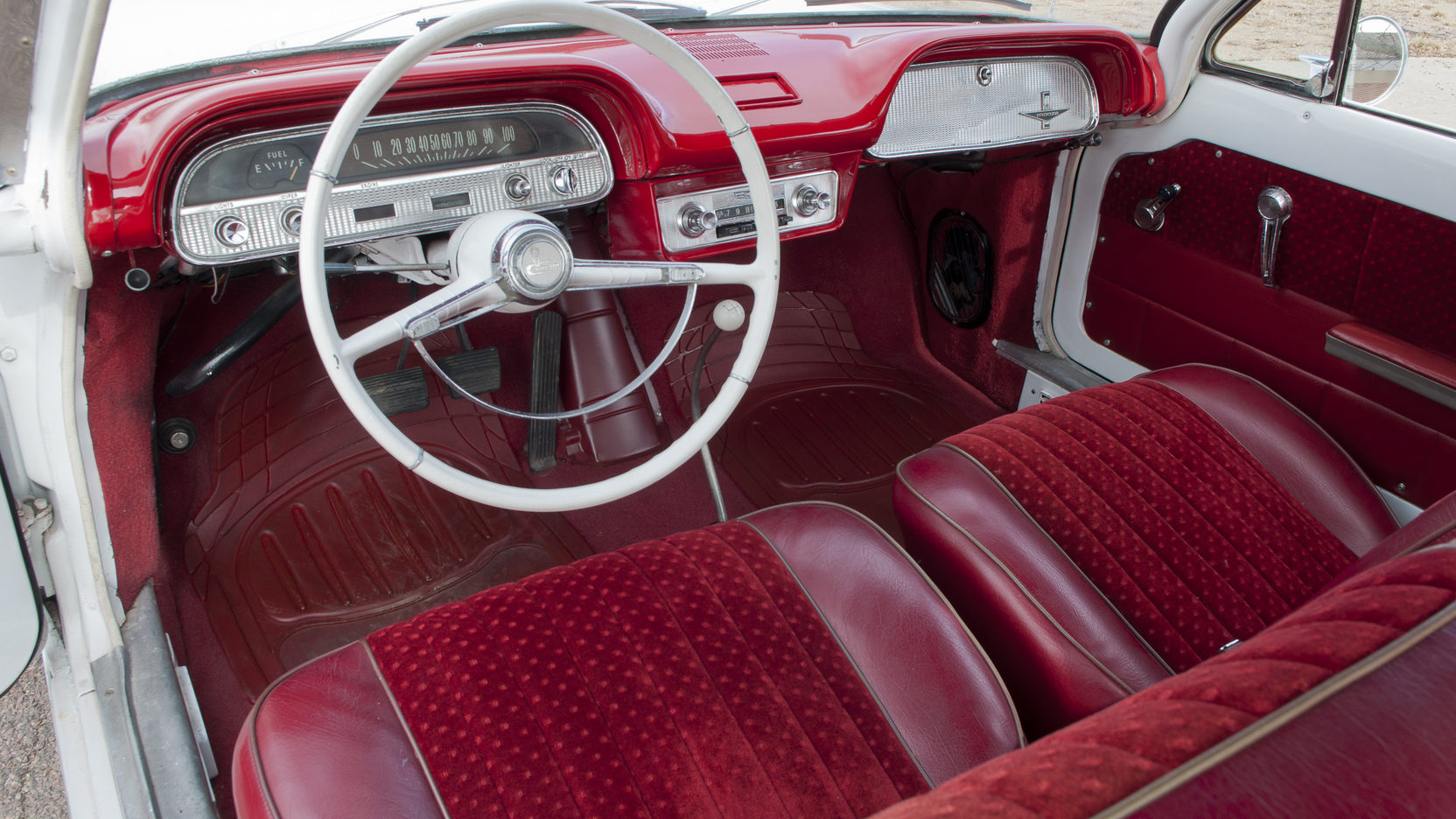

Even more intriguing, however, was Chevrolet’s approach to creating a family of automobiles based on the Corvair’s platform. To be sure, there were coupe, sedan, convertible, and wagon editions of the Corvair, a strategy that could be found across town at Ford with its Falcon, but added to this were oddities like a passenger van and even a cab-forward pickup truck. The latter were sold under the Corvair 95 banner, with a Corvan panel van and Greenbrier pickup and passenger van (with seating up to nine passengers) fleshing out the lineup.

Again, it was a clear case of GM taking cues from Volkswagen, which was scoring big with its small, yet useful rear-engine van (and significantly more rare pickup). Chevrolet would add a quirky Rampside version of the truck featuring a side ramp for cargo loading, as well as the Corphibian, a one-off amphibious pickup. On the commercial side, the versatile Corvair platform would also spin off tiny military tanks (the Corvair DynaTrac) and a training version of the eventual Lunar Rover for NASA.

After the disappearance of the Corvair, it would be several decades before General Motors would attempt to link seemingly disparate body styles under the same name (the Lumina van, sedan, and coupe in 1990), but by then the moment had passed and Chevrolet no longer had the market momentum to make the concept work as anything other than a novelty.

What might have been

Looking back, when a car goes from selling nearly two million models in its first generation to a mere 160,000 spread out over a five-year flameout, it’s easy to understand why a company like General Motors would have been gun-shy about advancing any ideas that had been associated with the Corvair project.

Still, it’s a tragic realization that so many promising—and, as time would illustrate, important—technologies and initiatives were tainted internally by the Corvair’s legacy, reaching the point where GM would sit on the sidelines of change as long as possible before reluctantly giving in to market forces.

With the Corvair platform, Chevrolet possessed an advanced, lightweight, reasonably efficient, and (after its suspension redesign) fun-to-drive compact car that would have perfectly positioned the company to deal with the upcoming energy crisis. Instead, the Corvair was replaced by the popular, but far more conservative engineering of the Camaro. And while the F-body has blossomed into a classic, its me-too product attitude never matched the in-era sales of the Ford Mustang it was trying to imitate. The Camaro was definitely not the answer by the time the mid-’70s rolled around (and neither was the decidedly low-tech Vega), as GM saw its market share erode while imports from Japan established an efficiency-based compact foothold that would kick the American market wide-open by the 1980s.

The Corvair family, had it stuck around, could have provided Chevrolet an efficiency-oriented sub-brand poised to dramatically improved the company’s fortunes during a very difficult time for the auto industry. It’s the closest thing Chevrolet ever had to legitimate in-house division of its own, with a built-in market and a strong development team backing it up. Can you imagine what the ’80s could have been like had a high-tech Corvair descendent displaced the lamentable Chevette as a fuel miser?

Turbocharging represents another missed opportunity for GM to have cemented a leadership role on the tech front. When the Corvair Corsa left showrooms in 1965 it would be another decade before Americans had the chance to sample turbos once again—and it would come in the form of the Porsche 911, a far cry from the attainable Chevrolet. Although the computer controls required to take turbos into the mainstream were just a dream in the ’60s, the Corvair cast a long shadow over forced induction development in small cars at General Motors, one taking decades to dispel.

Corporate cultures take a long time to change, and bad memories often reverberate more than good ones down the hallways at HQ. Is it a stretch to link the Corvair’s failure to GM’s decision in the 1990s to walk away from its EV-1 electric car program, the most disruptive, and advanced product the company had ever attempted to build? I don’t think so—not when comparing how resistant to anything resembling the status quo Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick, et al became once the final Corvair had slunk off the assembly line. Corvair-thinking became persona non grata at GM, and with no more appetite for public shaming, the will for engineers, product managers, and executives to step out of bounds disappeared almost completely.

It’s safe to say that things have changed for the better at post-’90s GM, and that the threat of another Corvair-level development freeze seem unlikely—otherwise, the Pontiac Aztek debacle would have killed the company’s crossover craze right in its tracks. It’s a good thing, too, because at the pace of the current market, turning your back on technology to avoid potential embarrassment is more likely to earn an epitaph, rather than a do-over.