Media | Articles

Piston Slap: Hybrid Engine Wear When Cold?

Bob writes:

The Piston Slap about Sue’s Forester was great! I was going to email this question to you anyway, then found that her issue is very much like mine: I have a 2014 Forester non-turbo that bought new in April 2013. It began using oil after a few years, I had the short block replaced gratis by Subaru yada, yada, yada.

(Unfortunately the second short block went even FEWER miles before oil consumption increased again. Subaru would not replace the block a second time. I added about 1.5 quarts between full-on changes every 4-5k miles. I also have a rather alarming clatter upon startup and it lasts longer than I’m comfortable with. I have about 124k miles on it and will probably trade it soon.)

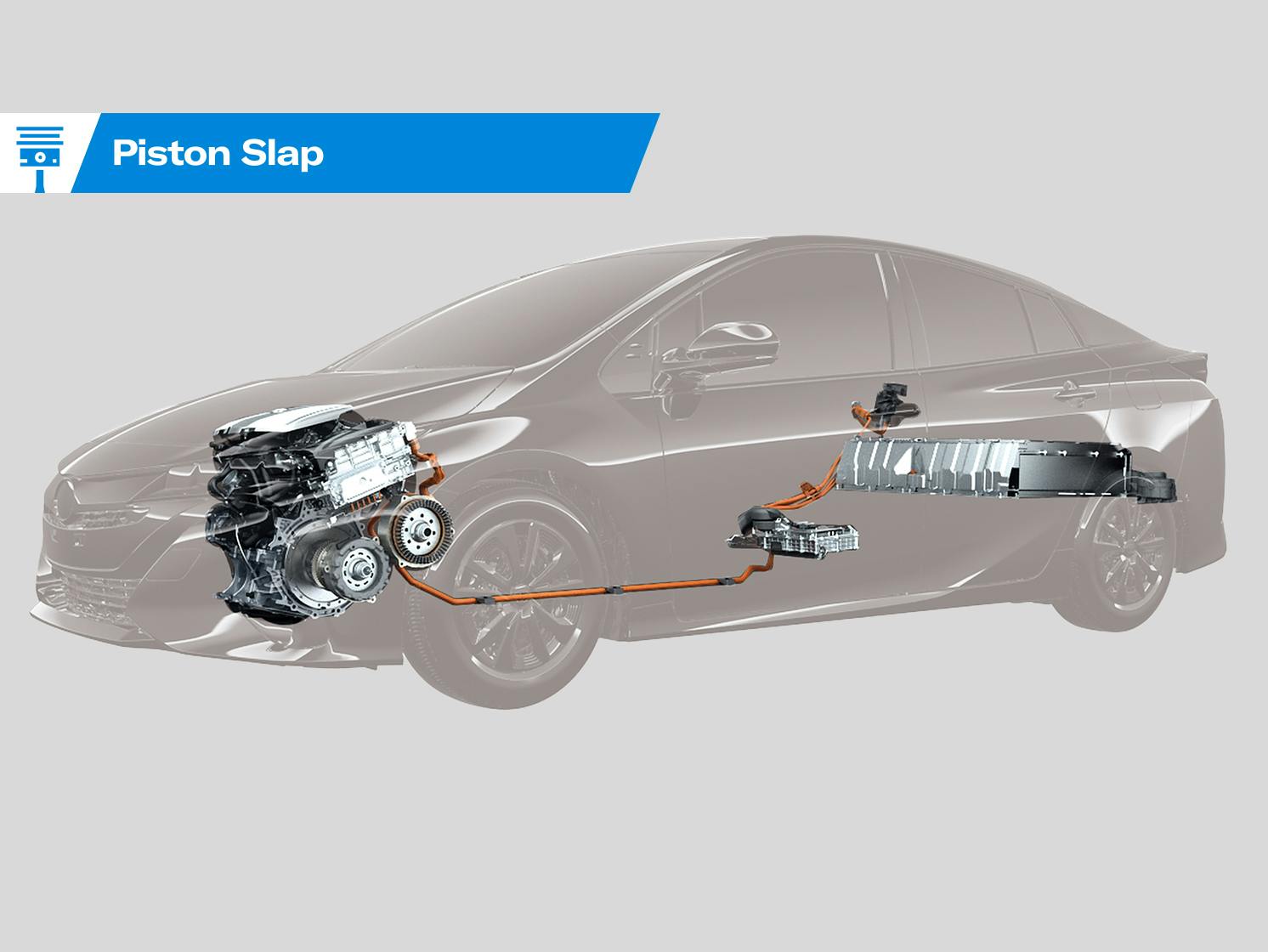

Now my question, and it’s also about engine wear: I have wondered about this scenario for years but never seen it addressed. How can it be OK for a plug-in hybrid to start off in the morning at, say, 10 degrees Fahrenheit (or 70F for that matter), on the battery only, then drive a few miles on battery to the freeway on-ramp, and then suddenly floor it and RAM ON the gasoline engine to get enough power to merge?

Is this not the worst thing that could be done to the poor ICE part of the drivetrain?

And a second, somewhat related question on plug-ins: just how sludgy could your gasoline get if your daily commute is within the battery range and it takes more than six months to use a tank of gas?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Sajeev answers:

Interesting questions! For starters, it absolutely is not okay for a cold engine on a hybrid to drive on the battery only to have the user “suddenly floor it and RAM ON the gasoline engine to get enough power to merge.”

But I have a feeling that drivers have been abusing cold ICE (see what I did there?) engines in this manner since the dawn of the motorcar, so there’s little we as a motoring society can do about it. Modern oils and computer controlled fuel/timing curves likely mitigate cold engine wear to some extent, but let’s look at hybrid powertrains specifically. Exhaust heating systems have been proven to save fuel in hybrid vehicles, and this is employed by Toyota along with several powertrain operation scenarios. These scenarios can be distilled into five stages that I’ll paraphrase:

- Stage 1: The gasoline engine is cold and starts up like a normal car to heat the catalysts/engine oil. (It likely operates in open loop like a regular gas engine.) This happens by default, and the only way to avoid this is to override the system by locking it into EV only mode (if equipped, and if battery capacity allows).

- This “default on” programming solves the issue in your first question, in theory.

- Stage 2: When an engine temperature mandated by the software is reached, the engine turns off as per the need from the driver’s right foot.

- Stage 3A: At the next increase in system temperature, the engine will not turn off. (Presumably because the driver is “giving it the beans” a bit too much?)

- Stage 3B: Full hybrid operation to maximize fuel economy above all else, but done outside of stop and go traffic. This is where the computer decides what’s the best use of gasoline and EV propulsion.

- Stage 4: Full hybrid operation like 3B, but no matter the traffic conditions.

Please note that my paraphrasing is far from gospel, as I’m only showing you how a hybrid powertrain algorithm might work in theory. Put another way, we learned in the same manner back in the 1970s when something called an oxygen sensor first told one of them newfangled computers how to spit out fuel and advance spark timing more efficiently. Knowledge was sparse, but the basics of engine control were available if you got your hands on the right training manuals or technical magazines of the era.

If you asked me a similar question about powertrain programming in 1977, I’d give you vague generalities on concepts like open and closed loop, and how a feedback carburetor works. Heck, we are lucky we have as much Toyota Hybrid information on the Internet as we do!

To your second question: I doubt six-to-12-month-old gas will sludge up enough to cause an issue with a modern fuel system. (Carburetors tend to be more finicky, and direct injection is likely the same.) While I do not recommend it, I once drove on two-year-old gas, as I had wrecked one of my cars on a full tank of fuel. (It took two years to fix the collision damage, and do a glass-out body respray.) Once the restoration was done, the car idled oddly and finally threw a check engine light as I gently burned off that old gas at low throttle inputs. Never again…at least not on purpose.

Gas degradation is real. I definitely go easy on the throttle until I can burn smelly old gas off and/or top it up with fresh gas. Buying a bottle of fuel system cleaner might help if a vehicle is subjected to old gas on a regular basis, or just buy gas with more additives for a Top Tier certification. In general, gas will last longer in temperature-controlled environments, especially if you can lower humidity levels when ethanol blended fuels are in play.

While the Internet is full of websites suggesting that gasoline goes bad after three, six, or 12 months, I suggest you do your own experiments with your unique set of variables to find your specific truth. Maybe keep a bottle of fuel system cleaner and a new fuel filter handy for the six and 12 month mark. You may never use the cleaner/filter, but your fuel injectors might be thankful for their presence.

Have a question you’d like answered on Piston Slap? Send your queries to pistonslap@hagerty.com—give us as much detail as possible so we can help! Keep in mind this is a weekly column, so if you need an expedited answer, please tell me in your email.

Sajeev has lined this out well in a general manner as he said. You need to look at each Hybrid as its own as they all use different systems and tricks. Then you have cars like the Chevy Volt that is totally different.

Most cycle the engine and run on the engine more than battery. It just depends on how it where you drive.

As for gas sludge take time a lot of time. But fuel can degrade and absorb moisture. This will make it run a bit rough in some cases.

But outside a Chevy Volt most Hybrids use enough gas to keep it fresh. The Volt will run all electric and will not use much or any gas. At least in the early models. I recall Keno said his Volt was still on the first tank of fuel a year later.

Just remember Hybrids have all the advantages and disadvantages of an ice and EV so you really need to follow up with each company on how they deal with it. There is often some extra care and service.

Might have the Subaru looked at. It may be just a tensioner or guide on the timing chain. The oil use is not unusual or excessive. It may be a better car than any hybrid you buy. My friend just list his Subaru but it had nearly 300k miles. Many of these hybrids will need a battery before that and not be cost effective at high miles.

My wife and I had a 2012 Volt. The engine would kick on, even with plenty of battery, under at least 3 conditions, if memory serves me correctly (there may have been more): 1 – Extra power needed for HVAC in the cabin, 2 – If the engine had not run in a set number of miles, it would run for 10 minutes, and 3 – If the gas had been in the tank for a year, it would then run the engine until gas was needed. We never experienced the 3rd one, but the other two, yes.

I would use fuel stabilizer or gas drier if I were using a plug-in hybrid like that to keep the gasoline fresh longer.

To add to what Sajeev mentioned based on owning a number of Ford HEVs and PHEVs from every FWD based generation.

For a standard Hybrid when it first starts and heat is requested the engine will start immediately and will not shut off until the engine reaches the “high” min coolant temp. Once that temp is reached the engine may shut down depending on the torque request and battery SOC. If it does shut down due to a light load, the vehicle being stopped for long enough with high heat demand the engine will restart regardless of torque demand or lack there of. This is only really a factor in colder temps with extended elevation loss, or other light loading. Either way the car will do everything possible to keep the coolant temp and inferred catalyst temp and the point where restarts will be efficient and clean, ie closed loop. That is something that holds across virtually all hybrids. The hybrid system as far as the mfg is concerned is an emission control system. So yeah you don’t want to kill all those savings from engine off operation by letting the engine get to cool enough to restart dirty.

In certain era Fords there is an option of an EV+ setting. In that case it learns places where cold soaks regularly occur. When it gets within a 1/2 mile radius of that location it will allow the battery SOC to go lower than normal and allow a higher current drain. This is down to leave as much “room” in the battery as possible so the excess energy generated during that initial warm up cycle has a place to be stored.

PHEVs work similarly, but as hyperV6 noted it does vary from mfg to mfg and in this case the variation is much greater.

All PHEVs, I’m aware of, have some sort of adjustable mode. In the case of the current Ford there are 4 modes.

“Auto” where under many conditions the engine will not start until the EV portion of the battery is depleted. If temps are low the engine may start up with a battery at a high state of charge because using the engine to heat up the cabin (and battery) is more efficient than resistive heating. It can also start the engine when torque demand exceeds what the battery/motor can supply. In either case when the engine starts it will run it very lightly initially and rely mostly on battery power. Once it has warmed up a bit the engine contribution will slowly ramp up while the battery contribution tapers off. Once the engine has started it will also continue to run until it reaches that min “high” temp. The difference is that if the engine start was initiated solely due to meet torque demand it may not restart. Every modern PHEV has this mode, even if it is the only mode it has.

“EV Later” Selecting this mode will maintain the battery SOC around the current SOC. Essentially it shifts the “portion” of the battery used for Hybrid mode. The idea is that you can force the engine to run when you know demand will be high and save the battery for lower load situations, ie once you are off the freeway, on a long down grade. Many PHEVs have a mode like this.

“EV Now” this mode will prevent the engine from starting due to torque demand but again may start the engine due to ambient temps to maximize the EV range, buy taking advantage of that waste heat, including that going out of the tail pipe with Exhaust Heat Recovery. Even fewer PHEVs have this mode.

“Charge Now” Again this will force the engine to run and will often run it in excess of current torque demand and use that to raise the the battery SOC. The reality is that there are limited cases where this isn’t less efficient that other modes and is mostly useful in areas where there are EV only zones. Even fewer PHEVs have this mode.

Much of the time I do run ours in EV Now mode and it give more than enough power to do everyday driving including 60-70 mph on the freeway. This time of year since we typically only charge to 80% IF I know I’ve got a longer trip I’ll put it in Charge Now mode for the first mile or so to force the engine to warm up faster and then switch to Auto or EV Now depending on the trip plan.

As far as the stale fuel thing goes, it less of a problem on modern cars than it used to be since current EVAP regulations require tighter sealing, reducing that amount of oxidation, moisture absorption, and evaporation of the lighter portions that can occur.

Since the computer monitors for fueling events as part of that EVAP check procedure the car is capable of inferring the age of the fuel and will eventually lock out EV mode until the fuel level reaches a minimum level. Again it depends on the exact vehicle but many do have a fuel maintenance mode of some sort, that will run it down until the low fuel light illuminates.

So the net is while it seems like Hybrids of either type have the potential for more engine wear, the computer acts to minimize it and in the long run the fact that the engine runs far less means wear is significantly reduced overall.

I forgot to mention that many hybrids don’t start their engines like a typical engine. With a typical engine when it gets a cam and crank sync it starts spraying fuel and making sparks. In some Hybrids the engine is spun much faster thanks to a starter/generator replacing a typical starter, Once it gets cam/crank sync it starts making spark but doesn’t start spraying fuel until it confirms oil pressure.

I would generally say that the wear on a hybrid should be better than the uneven wear of cylinder deactivation schemes. They should generally be fine as most are at the minimum going to be better lubricated than just stared cold ICE motor. Regardless I would say it’s always best to be gentle till operating temps are at normal.

Our Jeep Wrangler PHEV is happy to loaf around town all day on the battery. The ICE typically doesn’t kick in until you’re asking for more power than the battery alone can provide. As a result, the ICE often turns on when the gas pedal is near the floor. I don’t believe that there is any preheat, so the scenario is nearly full throttle on a completely cold engine. I cringe every time it happens. Are there any protections built into the Jeep’s systems that keep this from being as bad as I think it is?

did ‘bob’ mean “1.5 quarts between full-on changes every 4-5k miles” is excessive? btw, this equates to a little under 2,700 mi/qt.

Surprised no one has mentioned Ethanol-Free gas, which has a much longer storage life than gas blended with Ethanol. Ethanol-Free should last 18-24 months. I wouldn’t run anything else in a car that consumes so little fuel.

I remember a few years ago when a friend of mine took his at the time 1-year old Ford Escape hybrid to the garage in a panic because he thought it had a blown head gasket. His oil change place warned him about all the water that was in his oil. My friends had two hydbrid, a Prius that he used to run to the city (about 1.5 hours away) and the Escape that was 4wd that he would use to drive a mile to the coffee shop then a half mile to the library then a half mile home. Long story short, he rarely drove the Escape to the point where the engine needed to start, even in the winter. The extra quart of fluid that came out during his oil change and made it look like mud was all crankcase condensation that never cooked out like it normally would if the engine were run up to temp regularly.

He got rid of the Escape and kept the Prius, realizing he didn’t need two cars to save the planet.