Media | Articles

The bike behind the bathing suit: The first Vincent Black Lightning

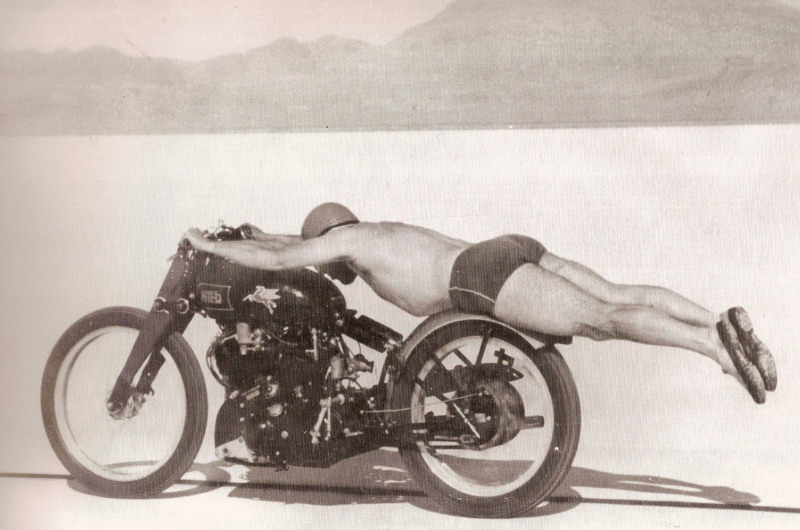

Sometimes, important moments are made truly historic with a single photograph. The sailor kissing a woman in Times Square on V-J Day in 1945. Cassius Clay standing over a downed Sonny Liston in 1965. The U.S. hockey team celebrating victory over Russia in the 1980 Winter Olympics. And, for motorcycling, Rollie Free streaking across the Bonneville Salt Flats aboard a racing Vincent, wearing nothing but a bathing suit, canvas shoes, and a shower cap. It is the defining image of what is now regarded as the quintessential Vincent bike.

The moment was in September 1948, when Free rode John Edgar’s Black Lightning prototype to a record of 150.313 mph. To gain a fraction more speed on the two-way run, he stripped down and laid prone atop the bike to reduce wind resistance. It was a terrifically brave maneuver, considering savage texture of the salt that would have torn Free apart if he fell. Together, the combination of rider daring, the breathtaking speed attained by what was really just a modified streetbike, and the click of a shutter turned this moment in time into forever famous.

The physical record of famous moments like this are fleeting, and surviving seven decades is a challenge for any mechanical device. But the bike Rollie Free rode on that September day is still with us, looking fresh enough for another Bonneville run. It’s on display at the National Motorcycle Museum in Anamosa, Iowa, as part of Streamliner exhibit that runs until spring of 2018.

20171129180504)

With their big 1000cc engines, Vincent V-twins have always been important in motorcycling, especially during the brand’s heyday from about 1948 to 1951. Vincent built 4,836 Rapide streetbikes, 1,727 higher-spec Black Shadows, and 33 race-spec Black Lightnings, including Rollie Free’s record-setting Black Lightning prototype. The base Rapide could go 110 mph, and the Black Shadow, resplendent in its black stove-enameled engine cases, could reach 125. Today, these production bikes are valued near or above six figures.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

But the bike Rollie Free rode that day isn’t just any Black Shadow, it was the very first competition-spec Black Lightning. Commissioned by car-racing sponsor John Edgar specifically for record setting at Bonneville, it featured a highly tuned engine, large open exhausts, and precisely zero extraneous bits. It was built for speed, and on the salt, it delivered.

Just as an aside, I recently tested the latest Honda CBR1000RR superbike at California Speedway. It is a stupendously fast machine, and on the NASCAR oval’s front straight—which is admittedly too short to allow the bike’s peak speed—the speedometer showed 150 mph. That’s exactly the same as Free’s achievement in 1948. While a buck-fifty on a motorcycle is easy enough to “buy into” today, 69 years ago it was nigh-upon impossible to achieve. Regardless, that kind of speed on two wheels remains an incredible life experience, so we can only imagine the exhilaration Free felt during and after his historic runs.

20171129180515)

After the Vincent’s racing days ended, Edgar used the machine on the streets of California before lending it to a racing acquaintance. Thereafter, it was sold to an automotive engineer who subsequently moved to Michigan, where the Vincent stayed for decades, in mostly original condition.

In the 1990s, Texas Vincent collector Herb Harris purchased it. Knowing well that authenticity is a key to value, he painstakingly researched and validated the machine, and in 2011 sold the bike to a collector for an undisclosed record amout. Since then, it has been occasionally seen at events and locations befitting its stature as one of the most famous and important motorcycles ever.

So why does this bike matter? The Bonneville record-setting Vincent didn’t become famous for a movie appearance, for celebrity ownership, or for winning some concours d’elegance. Rather, it is the one and only factory Black Lightning prototype, the actual bike that Rollie Free set his 150-mph record on, and the bike in that iconic photo. Thus, the “Bathing Suit Bike’s” uniqueness and record-setting provenance, along with its undisputed chain of ownership and “that photograph,” are more than just a good story. They’re solid gold—and the gold standard for motorcycle collecting.