Media | Articles

At RWM & Co., Mechanical Sympathy Comes with the Job

The broad, flat floodplains near Delta, British Columbia, don’t resemble England much, at least not with snow-capped mountains sitting on the horizon. Today, however, the weather is British, a constant drizzle falling in sheets and drumming on gently rusting steel awaiting its future life.

All the best workshops have a few interesting automotive carcasses scattered around back, and the nondescript building that houses RWM & Co. is no exception. It’s just that the metal’s not what you’d expect. Perched atop a shipping container is the body of a Honda S600, one of the pint-sized, 11,000-rpm screamers that were sold in Canada when the U.S. only knew Honda for its motorcycles. An Alfa Romeo Giulia Sprint GT retains its faded glory, despite a lack of motive power. And, in the corner, a chubby little Ford Thames Freighter appears to dream of greater things.

“That’ll be a race-transporter someday,” says Robert Maynard, founder and owner of RWM. Inside the building, an ear-splitting racket erupts, the telltale sound of a power-hammer bending metal to new purpose.

Maynard is, himself, a U.K. import. A graduate in mechanical engineering, he moved to Canada from England along with all his tools, including a very heavy cast-iron English wheel (to the English, this is simply a “wheel”). He founded his restoration company in 2013, and it has been growing steadily since. Currently, RWM has seventeen employees and two locations, one of which largely handles mechanical assembly and vehicle service. This building is where the manufacturing happens.

At the wheel of the hammer is Robert’s son Will, carefully smoothing and shaping the inner liner of a wheel arch. Will and his younger brother Charlie, each in their early twenties, are both taller than their father, but they listen carefully as he passes on the knowledge learned from a lifetime spent building things.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Modern workshops can be antiseptic in feel—open, brightly lit places built around impressing visiting clients. RWM’s main shop is spotless, and it branches off into various specialist work areas and supply storage. It has the feel of the a place that might exist anywhere from the Midlands to Manchester. It’s the sort of happy rabbit warren where you come around the corner to find the likes of a friendly Volkswagen Type 3 Syncro pickup truck, receiving a little rehab to the back sheetmetal after a rear-end shunt.

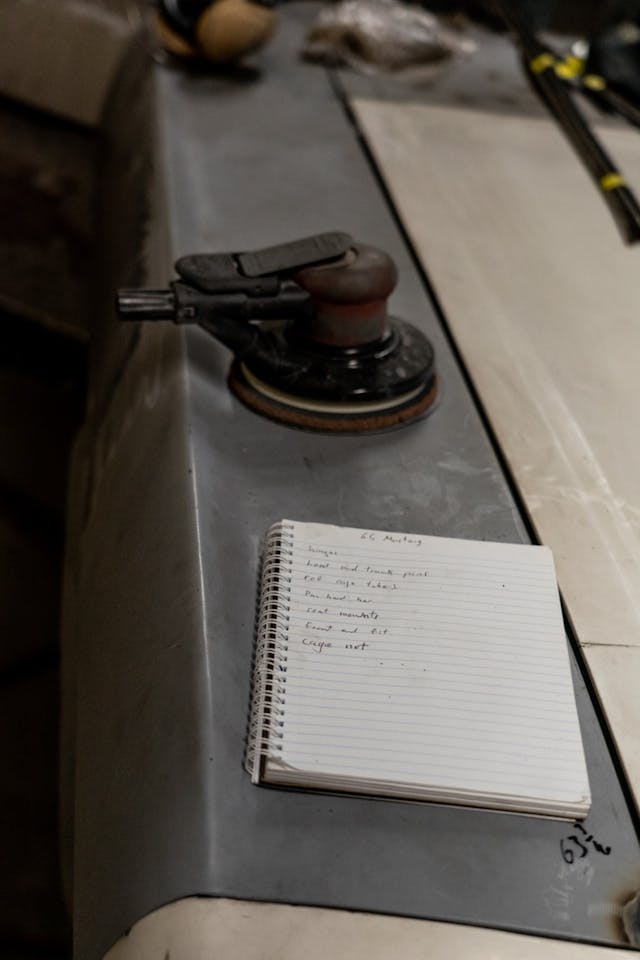

The VW is the most modern car in the shop, as RWM’s stock in trade more usually extends to classic Jaguars, Austin-Healeys, and Triumphs, and there are plenty of these here in various states of completion. And not just British fare: On this day a grinder unleashes a shower of sparks from a Datsun 260Z, while in another part of the shop a 1960s Mustang sits nose to nose with a BMW, all three receiving bracing and roll cages for the upcoming racing season.

“We don’t usually have so many race cars in the shop,” Maynard says, almost half-apologetically. “I was at Mission Raceway when someone had a crash, and I sort of jokingly said, ‘Do you need someone to straighten that?’ So we did, and then the word got out . . .”

Word of mouth is what makes or breaks a successful restoration shop, and after a decade in business, RWM has a roster of satisfied clients. Yet you also get the sense that Robert actually would rather be working on something than talking up past accomplishments. After pointing out a few highlights of his current project, a fascinating ground-up build, he’s off again, touching base with the young apprentices working throughout the shop.

That there are young faces working here is a heartening thing for anyone interested in the future preservation of automotive history. Modern automotive education produces technicians more than it creates mechanics. Diagnose, remove unit, replace. True mechanical sympathy takes patience and requires passion. Maynard talks about one of his apprentices, Tarek Baratta, finding that spark.

“His work experience wasn’t really working out,” Maynard says. “But on his last day here, we got a Ferrari in. I saw the way he was looking over it, and before he left, I told him if he wanted to come back, maybe that door was open.” Today, Baratta’s skills are excelling.

There are plenty of experienced hands at RWM as well. A few came over after longtime Vancouver Porsche replica-builder Intermeccanica closed down in 2022, and Maynard was happy to snap up skilled local talent. But others have come to the flock in what seems like an old-fashioned way. One senior craftsman, Colin Bailey, had been a panel-beater at a Rolls-Royce specialist in Ontario before moving west. He simply walked through RWM’s doors one day, looking for work.

“It’s more about what you can do,” Maynard says, “I care more about that than any piece of paper. It’s got to be a passion, not just a job.”

This motto of sorts extends beyond his work. At the annual Hagerty Spring Thaw Classic, a budget-friendly classic car tour through B.C.’s spectacular rural roads, you can often find Maynard in the sweep car, helping stricken participants limp to the next stop. Late at night, when others have retired to bed, he’ll be out there with his tools, getting some recalcitrant MGB or similar to behave.

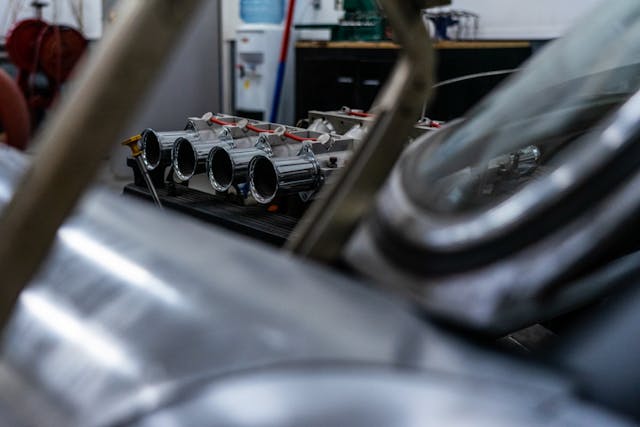

And then there’s Maynard’s current passion project, which is so far dubbed, the “Daytona.” A tube-frame construction with hand-shaped bodywork, it’ll be powered by a tuned 3.5-liter Rover V-8 paired with Alfa Romeo running gear; Maynard has long had an affinity for all things Alfa. It’s not a restoration or a recreation, but something entirely unique, built from a sketch to a clay model and now taking form in the metal.

Along with the layout of the workshops, the mix of craftsmen and apprentices, and the focus on quiet competence rather than showing away, this last adds a very English flavor to RWM. Any student of automotive history can reel off a list of exceptional machines built by Englishmen in sheds. At 12,000 square feet of workspace, RWM is more than just a shed, of course; it’s a bustling place with more than a dozen cars being worked on simultaneously, and constant turnover of projects of all varieties.

Yet, here on the wet west coast of British Columbia is a little slice of old-school English craftsmanship. The kind of workshop built on valuing skill and passion. A place where steel, rubber, and glass will come to life once again.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Seems like they cover a wide variety of classics. Love the blue on the 260Z!

The Synchro is not a Type 3, it’s a “T3”. The original Transporters were all originally “Type 2s”, and the generations were later denoted with T1 (Transporter 1), T2, T3, etc.

Beetles and Karmann Ghias were Type 1s, Transporters Type 2s, Squareback and Fastback were Type 3s (along with the Notchback and Type 3 Karmann Ghia, neither of which were sold in the U.S.) and there were later Type 4s in body styles similar to Type 3s, but mechanically much, much different and of unibody construction.

It gets more complex than that, especially with specific model types, but that’s the gist of it.

If I were a younger man and unmarried I’d consider an apprenticeship at this place. It’s exactly what I’d like to be doing now. I love that there are still places like this and young people doing the work. It’s a glimmer of hope in our otherwise sanitized, digital world we’re building for ourselves.

Front end of the Daytona looks like Mazda Miata, midships looks like Porsche 944 nad tail end looks like Corvette. 🙂

Great to see places and people doing what they love and turning out beautiful masterpieces. There’s hope after all.