Media | Articles

Suminoe Flying Feather: The Postwar People’s Car Japan Never Got

Call it a cyclecar or a microcar, the Suminoe Engineering Works Flying Feather was the right car at the right time for war-ravaged Japan of the 1940s. The driving force behind the car was Yutaka Katayama, now known as the father of the Datsun 240Z and the man who brought Nissan to the United States. However, his imaginative design met with a quick demise after only 200 examples were ever produced. The Flying Feather has become a forgotten car that should be held to much loftier status.

“Mr. K” was a Nissan man. Since 1935, he had worked for the auto manufacturer doing advertising and promotional work. After Nissan restarted production following WWII with its prewar Austin 7 DA and DB variants, plans were afoot to dive deeper into the Austin portfolio to bring more up-market sedans to Japan. Nissan was eyeing Austin’s A40 and A50, both larger cars than the ancient Austin 7.

But in 1947, Japan was struggling with ramping up production of even the most basic products. Raw materials, supply chain issues, a collapsed economy, and generally dismal working and living conditions didn’t translate to eager buyers of large English sedans. Katayama knew this, and felt that a bare-bones economy car was the way to kick off not only the rebirth of Nissan but also that of Japan. It was the same rationale that produced Germany’s Beetle and France’s 2CV. Both vehicles would begin production in 1947, the same year in which Katayama began envisioning their Japanese counterpart.

Nissan designer Ryuichi Tomiya was of a like mind with Katayama. Well-known throughout Japan for his various automotive and industrial designs, the future director of the Tomiya Research Institute would go on to design several important cars including the Fuji Cabin three-wheeler. Back in the 1940s, he was not up for rehashing Austins even though Nissan was dead set on going upmarket with the larger Austin A40 sedan.

Tomiya and Katayama hatched a plan to break from Nissan and start their own automobile company, focusing on affordable but sprightly commuter cars. They settled on a design they called the Flying Feather: An extremely simple, lightweight, two-seater with the presence of a peculiar yet sporting coupe. Yes, it would run motorcycle wheels and tires. And, yes, power would come from a puny one-cylinder air-cooled Nissan engine, located in the rear of the car, no less. But since the vehicle would not be much more than two motorcycles stitched together, it would be simple to repair, easy to build, and peppy enough to satisfy those who needed basic transportation.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

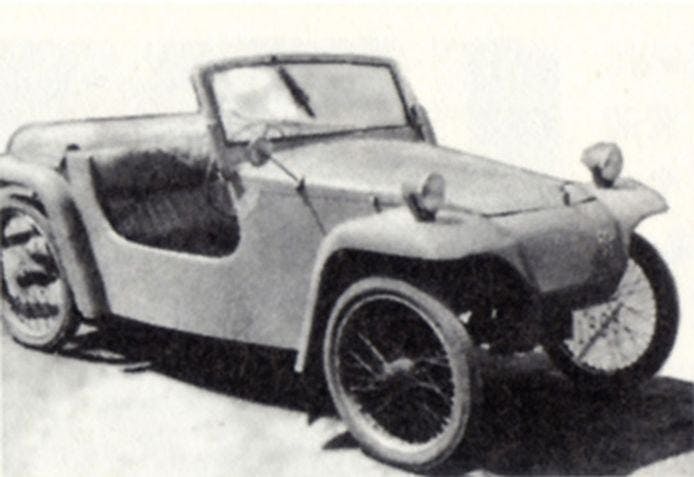

By 1950 Katayama was able to produce his first prototype, a doorless convertible somewhat like a stylized Jeep on motorcycle wheels. His first problem was getting the prototype out of the second-story shop it was built in, but once Nissan saw the elegant little doorless convertible, executives were impressed, and they agreed to produce the Flying Feather. Nissan was ready to produce its own version of Austin’s A40, and the Flying Feather would broaden the company’s portfolio by providing a smaller, cheaper option.

What appeared to be a solid production plan quickly fell apart after Katayama brought food to workers who were striking at a Nissan assembly plant to protest poor working conditions and constant interruptions for lack of materials. Nissan quickly parted ways with Mr. K—and his Flying Feather.

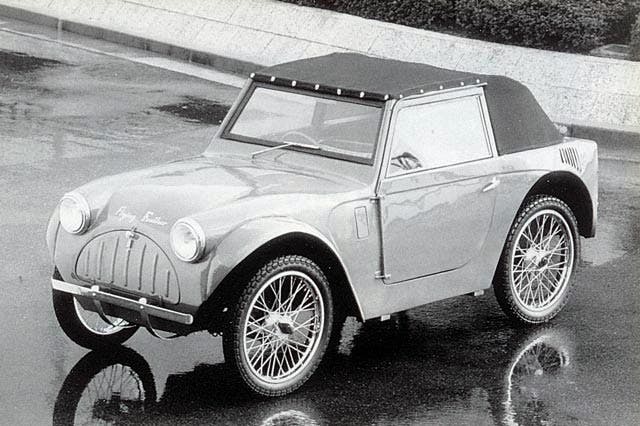

Undeterred, Katayama and Tomiya struck out on their own. A second, more stylish prototype would be the basis for the production-spec Flying Feather. Bug-eye headlights blended nicely into the hood, or frunk. A tapering body incorporated flares covering the front tires, with the body moving out as it flowed to the rear. The design ended with tall air vents chopped off at an angle. With large wheel openings for those big motorcycle wheels, it presented impressive overall proportions, adding to its diminutive though sporting look.

The refined prototype now had doors, independent front and rear suspension, and an air-cooled 350cc V-twin engine offering 12.5 hp. In this final form, the Flying Feather weighed 935 pounds. It was light as a proverbial feather, with better performance than the first design.

The windows swung up on hinges, rather than rolling up and down, and no radio or heater was offered. There were friction shocks to suppress jounce, and brakes only at the rear. The interior was spartan: The frames of the seats were exposed—from the side, you can see the springs—and covered with a fabric pad that served as upholstery.

After shopping the car around to suppliers, Katayama landed at Suminoe Engineering Works. It produced interiors and small bits to Nissan and agreed to produce the Flying Feather. Adding additional air beneath the wings of Katayama’s project, the Japan Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) agreed to help nurture Japan’s own “people’s car.”

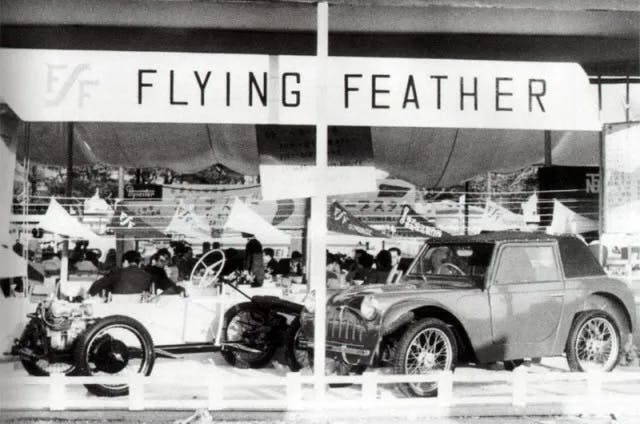

A production version of the Flying Feather—the “smallest, cheapest, and most economical practical car in the world”—was the highlight of the 1954 Tokyo Auto Show. Unfortunately, things quickly fell apart.

The MITI support never materialized. Then, Suminoe lost its contract to supply interiors to Nissan, which bankrupted the supplier and pretty much ended any possibility of producing more Flying Feathers. In the end, only around 200 were made. Very few have survived, and only a handful of restored examples exist today.

Though Katayama’s dream of an affordable car for Japan was gone, he wasn’t done with ambitious projects. He mended fences with Nissan, starting as team manager for Datsun’s two 210 entries in the 1958 Mobilgas trials in Australia. In 1960, Nissan sent him to America to oversee the launch of the Datsun brand. Though strained in these early years, Katayama’s efforts as the first president of Nissan of America laid the foundation for the expansion of the company. The Datsun 510, the 1600 and 2000 sports cars, the successful racing alliance with Peter Brock’s BRE Racing in the late 1960s and 1970s, and the development of the 240Z all happened under the stewardship of Mr. K.

In 2009, at 100 years old, Katayama remained immersed in the machinations of the car industry, offering his take on the impact of the Mazda Miata as the 240Z’s successor. He died at the age of 105, his reputation as a leader in the development of the Japanese and American automotive landscape well established. And while the Flying Feather is but a sidenote of his illustrious career, it really was a milestone in the reemergence of Japan and its burgeoning automotive industry.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

When I read that the builder was a supplier to Nissan I instantly thought “oh-oh”. Yep, I’m unsurprised at the outcome. 🙁

It’s a clever design and indeed does seem perfect for the era.

I did not know about this car. a humble start for Mr K.