Media | Articles

The Twisted Task of Replacing Serpentine Belts and Tensioners

The last two weeks, I wrote about repairing the exhaust in my recently-purchased 2008 Nissan Armada and getting the car inspected. With it legal, its intermittent Check Engine Light (CEL) issue faded into the background, and the punch list of needs became: 1) replacement of the front struts (it banged loudly over uneven terrain), 2) diagnosing and addressing a number of minor leaks, and 3) dealing with a loud metallic rattle from the front of the engine, almost certainly associated with the serpentine belt path. As belts are part of my “Big Seven” things likely to strand a car, I addressed this one next.

The so-called serpentine belt on a modern car is a very different beast than the quaint “fan belt” on a vintage car—that old narrow V-profile belt that spins the alternator, water pump, and the pump’s pulley-mounted fan. Unless you own an air-cooled Volkswagen, where belt tension is changed by removing washers to make the groove in the pulley shallower, V-profile fan belts are manually tightened by pivoting the alternator on a tensioning track. Loosen the bolt that holds the ear of the alternator to the track, pivot the alternator to slide it on the track until the belt is snug, tighten the bolt, done. It takes maybe a minute. If the belt snaps, replacing it is trivial. You just need to pass the new belt around the fan, loosen the alternator’s tensioning bolt, put the new belt on the crank, water pump and alternator pulleys, and tension it. If the radiator has a fan shroud, it’s a little more challenging to get the new belt around the fan, but it’s still an easy roadside repair.

Manually-tensioned V-belts are simple, but they do have issues. Both the alternator and the tension track typically have rubber bushings in them, and with age, heat, and oil, they wear out, causing the alternator to cock forward at an angle, which makes it so the belt will never stay tight. At some point the belt may begin to slip, which can cause the water pump to stop spinning and the coolant temperature to head into the red. In addition, cars that had what were then luxury accessories like power steering and air conditioning typically had separate V-belts for each, whose tension needed to be adjusted individually.

In the 1980s, things swung in the direction of cars having a single, wide, automatically-tensioned, grooved serpentine belt—so called because of the snake-like path it takes through all the pulleys. Serpentine belts don’t require tension adjustment. Instead, a spring-loaded or hydraulic tensioner has a pulley that leans against the belt. In addition to the pulley on the tensioner, there may be another idler pulley that routes the belt. Generally, if a car has a serpentine belt, there’s only one and it runs everything, but there are exceptions—my 2003 BMW E39 530i has two, with the second one running the A/C compressor, and each having its own tensioner.

The big advantage of serpentine belts is that they’re maintenance-free (if by maintenance you mean manually adjusting the tension). And, because the alternator doesn’t need to provide the tension adjustment, it mounts rigidly, so it’s far less likely to cock from worn bushings. But as with most things, there’s no free lunch, and a serpentine belt creates several challenges.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The first is that the serp belt, like any belt, is a normal-wear-and-tear part that needs to be replaced, and as is the case with many things on newer cars, that’s far more difficult than with an old-school V-belt due to the tightly-packed nature of components in modern cars and the torturous path the belt often takes. On rear-wheel drive cars with longitudinally-mounted engines, the tight access makes it difficult to even see the belt, much less remove it, without first removing components like the air box.

On front-wheel-drive cars with a transverse-mounted engine, because there isn’t a belt-driven fan aimed at the radiator, electric radiator fans are used. You’d think that would translate to an advantage that the belt isn’t hidden inside a fan shroud, but on our Honda Fit, the belt is so close to the side of the engine compartment that it’s necessary to remove a wheel and the inner fender liner to access the belt and pulleys.

In addition to the belt itself needing to be periodically replaced, the tensioner pulley (and the idler pulley, if there is one) spins on bearings, and over time, they wear out. The indication often starts as a high-pitched whine, transitions into a marbles-whipping-around-a-metal-bowl sound, then settles into a screechy metallic howl as it nears failure. And the tensioner itself can fail, though that’s less common.

The third issue is that replacing the belt requires relieving the tension by rotating the tensioner in the opposite direction it’s using to tension the belt, and that’s often not easy, both because it’s not clear where or how to grab it (some tensioners have a hex-head bolt you put a socket on, others have an Allen key or a Torx socket, and on some you grab the central nut on the pulley itself), and because accessing it and being able to move a long-handled ratchet wrench far enough to de-tension the belt is difficult. You typically need to search an enthusiast forum to find out which technique your car requires.

Another thing to be aware of is that while V-profile belts always sit in the V-groove of a pulley, one of the things that enables serpentine pulleys to be so, uh, serpentine is their ability to wrap around pulleys in either direction. The crankshaft pulley that supply belt power and things that use power (the alternator, power steering pump, A/C compressor) always have a grooved pulley with the belt’s grooves sitting in it, but the tensioner and idler pulley may be grooved or may have a flat surface that presses against the back of the belt, depending on the belt routing that’s required.

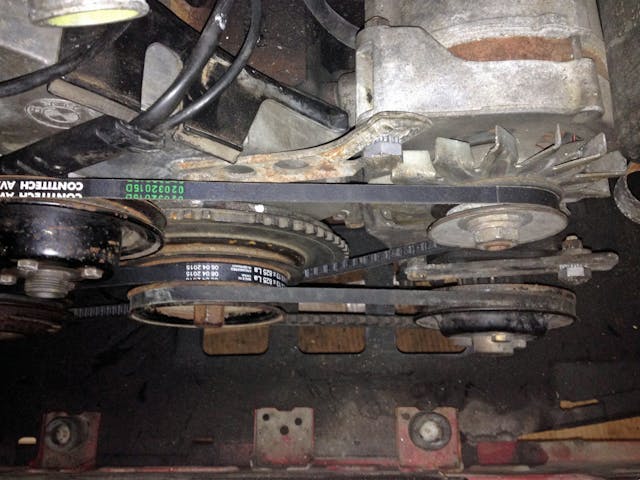

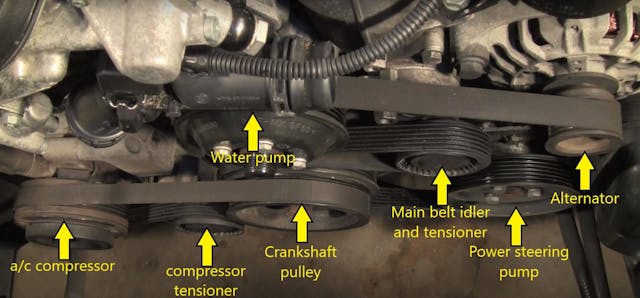

I encountered all these issues on the Armada. Something in the belt train was clearly making noise, particularly on cold start. It wasn’t yet at screechy howl; it was more like a hollow metaling ringing. I used my mechanic’s stethoscope and found that both the tensioner pulley and the power steering pump were loud (the steering also groaned when cold, further implicating the PS pump). However, other things in the belt chain—the alternator, the water pump—can certainly make noise as well.

There’s a technique you can use to isolate the problem, or at least get data that corroborates that of the stethoscope. The trick is to de-tension the belt, carefully lay it to the side of one component at a time so you don’t lose the belt routing, and test each component by spinning its pulley by hand as well as grabbing the pulley and checking it for play. I did that and immediately found that the bearing in the tensioner pulley was worn to the point of noise and obvious looseness. Surprisingly, the power steering pump felt fine.

So, what to do?

When you find a bad tensioner pulley, you have several choices. You can replace only the pulley, or you can buy a new tensioner with a new pulley attached, or you can buy a kit with a new belt, tensioner/pulley, and idler pulley if there is one, and do it all. The Armada’s belt looked absolutely fine with no cracks or dry rot, and the idler pulley was quiet. I usually choose the money-saving route, but because there was a break in the weather where I could do the repair, and Amazon could get me a Gates belt-tensioner-idler kit next day for $115 (whereas the a la carte options had longer shipping times), I opted for that.

The only power steering pump I could get next-day was an unbranded Chinese-made one of questionable quality, so even though it made sense to pull the belt off and do the two repairs together, I separated them and ordered a well-priced, low-mileage OEM Hitachi PS pump from a New England recycler, knowing it would take two days to get here.

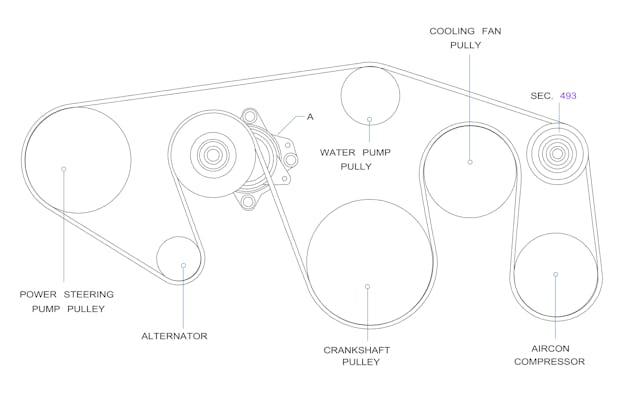

I’d already figured out how to de-tension the belt to do the component test, so removing it was easy. I first downloaded an image of how the belt routed around all the pulleys, then verified that it was correct for my vehicle. I realized that the Armada is a little unusual in that the mechanical cooling fan (and its viscous clutch) doesn’t ride on the front of the water pump but on its own pulley, essentially creating a second idler pulley, so it wasn’t my imagination that the belt path appeared particularly convoluted. Fortunately, the engine compartment in the Armada is big enough that everything was accessible without having to do anything like removing the fan shroud, so replacing the tensioner assembly and the idler pulley was easy.

What was far more challenging than I expected was getting the new belt on. I foolishly thought that, to thread it onto the pulleys, all I needed to do was pass the belt between the fan and the shroud and pull it over the fan. It took me over an hour to fully understand that the only pulley that’s “inside the fan” is the fan pulley itself, and that the fan pulley was smooth, so it needed to run against the back of the belt, not the grooved part. After several attempts, I learned that the trick to putting the belt on was to take a loop of it oriented with the grooves facing outward, pass it over the fan, then put the flat back of the belt on the fan pulley. Everything else could then be placed on its pulley.

Except, of course, the tensioner. New serpentine belts are typically much tighter than old stretched belts, requiring the tensioner to be rotated much further back than was needed to release the old belt. While I was able to release the old belt using a ratchet placed from the top of the engine compartment, getting enough clearance to put an 18-inch pipe on the end of the ratchet handle required me to do it from beneath the car. I also employed the trick of using strong clothespin-style clamps to hold the belt onto pulleys that it kept sliding off during belt routing.

Getting the belt on was enough work that I didn’t look forward to having to do it again when the replacement power steering pump arrived. Although I was certain that I needed to replace it, I gave the pump a look while I was under the car. I noticed that one of the bolts on the pump bracket was loose, so I tightened it. And, although the whole issue of fluid leaks was a separate task, there was an obvious and non-trivial leak of power steering fluid from where one of the rubber PS hoses mated to a metal line. The Armada uses spring-style, constant-tension clamps for all the coolant and power steering connections. While I understand the theory behind their use, I hate these clamps, as in situations like this, there’s no way to tighten them. I used pliers to loosen the clamp, moved it backward on the hose, took a conventional worm-screw-style clamp, opened it up, slid it over the hose, closed it, and tightened it down.

I then started the Armada. Not only was the ringy rattle from the belt tensioner pulley gone, so was the noise from the power steering pump.

No way!

I thought it was a fluke, so I waited until the following 32°-morning and tried it again.

Quiet as a church mouse.

I’m not certain whether the power steering noise I was hearing through the stethoscope was just a rattle from the bolt loose on the bracket, and whether the groaning on cold turning was due to pressure loss from a little fluid leakage, but for now there’s nothing wrong with it. I need to decide whether to spend the shipping to return the $80 used power steering pump, or put it on the shelf in the garage for when the thing really does fail.

So. Armada exhaust? Done, at least for now. Belt-and-related-accessory noise? Done, at least until the power steering pump rears its head. Next week: fluid leaks.

***

Rob’s latest book, The Best Of The Hack Mechanic™: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem is available on Amazon here. His other seven books are available here on Amazon, or you can order personally-inscribed copies from Rob’s website, www.robsiegel.com.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Both belt systems have their good and bad applications.

There are some v belts you can change anyplace anytime. But there are others you have to be under the car to change them and that is not going to happen on I77.

Same for the Serp. Most of the time you can change them pretty easy but then there is that one that pops up like my Supercharger belt on my SSEi that retired the engine mount to be remove. Not hard but not something you are going to do in a parking lot with out a good jack.

Over all I have had best service and reliability with the serp belts. Only ever lost one and most have been easy to replace.

Just make sure you have a diagram or a photo before you remove any belt. It will save you pain later.

Sometimes with serpentine belts it takes getting a leprechaun (can we say that) in there to get the belt going the right way around everything. They do last longer and typically easier, MB 560sl has five v-belts and can be a handful literally.

I’ve tried the stethoscope trick, and that noise resonates through everything. It resonates through some things better than others, and I have replaced an alternator or two only to find the source of the noise was something else. I have two serpentine vehicles with mystery noises I have never been able to chase down. An intermittent chirp in one, and an intermittent high pitched screech in another. I have checked and replaced enough components to be confident the vehicles will not leave me stranded.

Serpentine belts are one of those things that give the first owner trouble free life in that first 100k miles. After that, they become annoying, noisy, pesky little devices that drive folks like us nuts. I had one manual tension serpentine car that was trouble-free well into 200K miles, so I suspect that a lot of the problems are induced by the harmonic undulation of a spring-loaded undampened tensioner.

V belts screech from time to time, but will never leave you stranded unless they are ignored to death

In addition to its inherent efficiency, the advent of the serpentine belt accessory drive system enabled the physical packaging of engines within vehicle engine bays that would not have been possible with multiple (stacked) v-belts. The 1st use of an automatically tensioned single “poly-v” belt (serpentine) accessory drive system was introduced on the 1979 5.0-liter V-8 Mustang. Accessory drive systems are subjected to harsh under hood vehicle exposures & environments.

Both mechanical & hydraulic automatic belt tensioners must have internal dampening. In addition to the transmission of engine firing frequencies at the crankshaft pulley, each driven accessory drive component introduces unique harmonics into the belt system that need to be dampened by the automatic belt tensioner. Usually coulomb (friction) dampening is utilized in mechanical tensioners & viscous dampening in hydraulic tensioners. Automatic accessory drive belt tensioners usually originate as system-unique proprietary designs. Both types are required to be designed by their OEM manufacturers to function “maintenance free” for 100k+ miles. As with most aftermarket/replacement parts, OEM quality, via the original manufacturer(s), as well as lesser quality ‘cloned’ aftermarket-only manufacturers’ accessory drive system parts may be available.

Paul, thanks for that detailed but concise bit of technical information.

I deal with serpentine belts all the time and really like them. Many front wheel drive cars are a real pain but would be worse if v-belts were used. But I cringe when I have to deal with stretch belts when there is no room for the all but useless installation tool and have to use zip ties to hold the belt in place while turning the engine.

Replacing a belt on my Toyota or my old Subaru’s was very easy. Easy access to get in and out.

“The separate fan, power steering, and A/C V-belts on my 1973 BMW 3.0CSi.”

Rob, when did you put an M20 in your CSi? :^)

Jbbush, whoops! Busted! (I have a folder of jpegs labeled “belts,” saw the red paint on the bottom of the nose panel, and assumed it was my E9. I am ashamed…)

Judging by the belt routing on the Armada, and the story describing the PS pump leak, I’m surprised you haven’t had an alternator problem yet. Toyota 1UZ engines have the alternator directly underneath the PS pump. Pump leaks commonly result in alternator failures soon after. 1UZ engine owners are wise to address pump leaks as soon as possible to mitigate the expenses later on down the road. I think some Honda K-series engines have the PS pump up high also. An unfortunate location, depending on whether you’d rather replace a PS pump or alternator, I suppose.

Also, doing a (for example) A/C delete on a car can be more troublesome with one serp belt. Finding the right belt on Rockauto is the easy part as you can simply search for 6PKxxxx, where xxxx is the belt length of interest in millimeters (or 5PKxxxx, if it’s a 5-rib belt). But ensuring that without the compressor the belt doesn’t hit anything else, or have enough wrap on the other accessories, could be a challenge.

Nissan obviously knows what they’re doing, but the water pump in that routing sure doesn’t look like a slip-free set-up. Weird.

I do like the way that in the diagram Nissan have 2 bob each way on the spelling of pully/pulley.

Went through pretty much the same routine with my 200K mile BMW 318ti, except going through 2 crappy, cheap, leaking from new, chinese rebuilt power steering pumps before springing for a decent NAPA rebuild.

If you send the pump back, it will fail within 3 months. If you put it on the shelf it will never fail.

Thanks for another great article, Rob.

I’m reminded of how our wise Teacher, Dick O’Kane, described belts as “a licensed, practicing bitch…”

Changing the belt and tensioner was on my list for the 100k service of the Chrysler Pacifica 3.6, but realized that one of the coolant hoses needs to be disconnected in order to remove the belt. That, in turn, would include a coolant flush and fill, which should be done but I wasn’t prepared for. That will wait til next time, if I don’t trade the car in first.