Media | Articles

Work, Wheels, and Wood: A conversation with Taylor Guitars and Singer Vehicle Design

You’ll be surprised how much acoustic guitars and bespoke Porsches have in common. Fourteen years ago, no one thought the world needed custom Porsche 964 restorations worth well into six figures. Forty-nine years ago, nobody thought the acoustic guitar was in need of reinvention.

In each case, a wildly successful Californian company has since proved the naysayers wrong while teaching us something about the reinvention of old ideas.

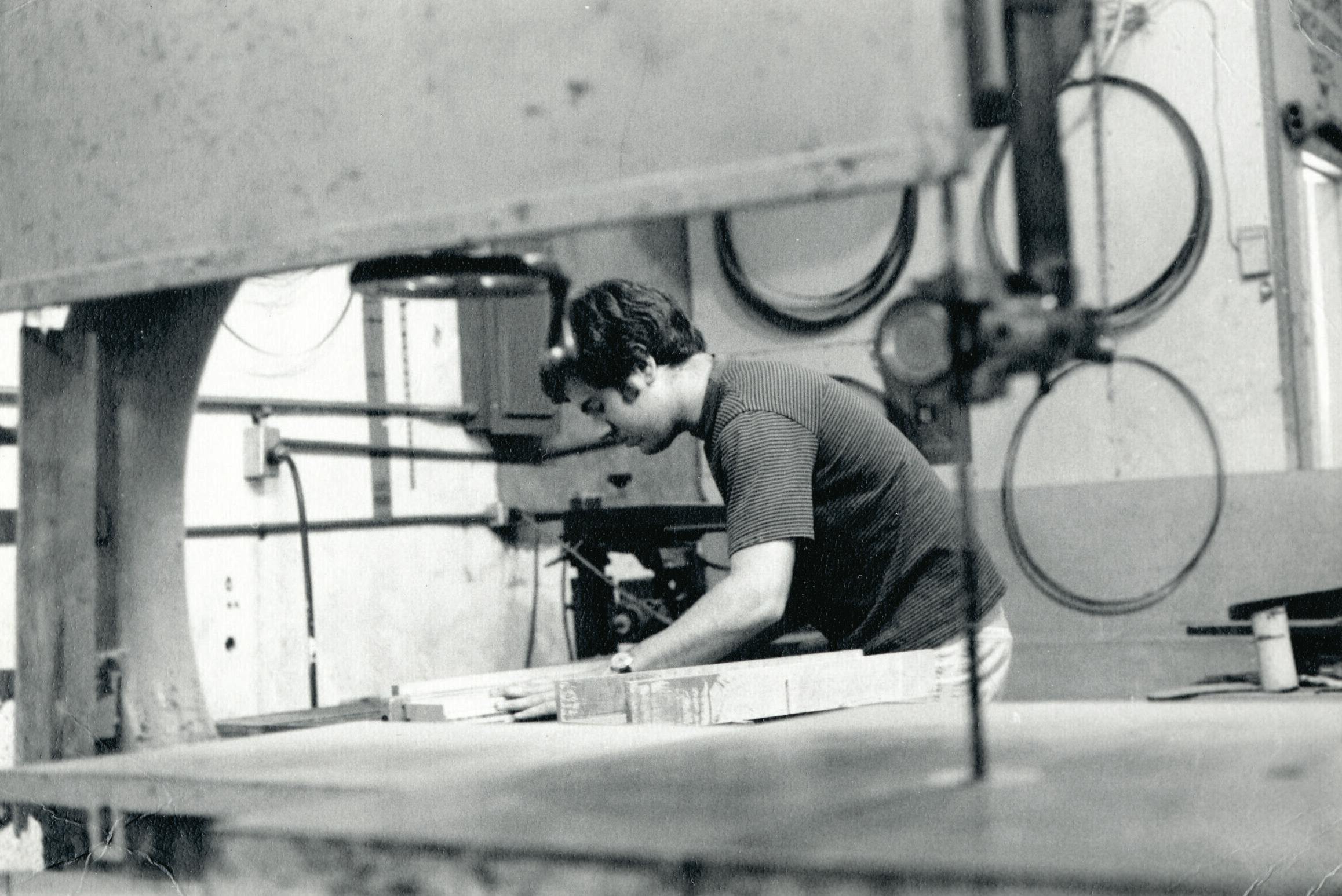

Taylor Guitars was founded in 1974 by Kurt Listug and Bob Taylor. In the decades since, they have brought modern engineering and fresh thinking to an industry dominated by tradition and fuzzy intuition. Through CNC machining and constant innovation, the company has grown into one of the world’s largest builders of acoustic instruments, but also a compass for the guitar industry, influencing even legacy giants like Martin and Gibson.

Singer Vehicle Design is younger. English expat Rob Dickinson found public exposure in the 1990s as the vocalist for shoegaze band Catherine Wheel. In 2009, he started a company to “reimagine” the Porsche 911 through heavily customized, ground-up restorations. Singer’s jewel-like work costs as much as a West Coast house and looks it, but it also launched an industry, birthing countless copycats. Singer reps won’t admit this publicly, but the company’s work is so good, it’s admired even within the executive suites of Porsche itself.

Happily, Dickinson and Listug know and respect each other. The former owns and plays a Taylor, while the latter, a longtime 911 fan, just took delivery of a Singer restoration after a four-year wait.

Mindful of all this, we toured Singer’s new restoration facility in Los Angeles. After that, we visited Taylor’s modern San Diego factory. Finally, we sat down with Dickinson, then Listug, and then Taylor’s new CEO/chief luthier—the architect of its recent renaissance—Andy Powers.

We met these men separately but asked each the same questions—on creativity and inspiration, but also on how you make something new in a hidebound environment. Their answers comprise the virtual roundtable on the following pages.

All three men love machines and music and view both in unique ways. (Powers even drives a vintage pickup to work and wrenches on it himself.) But enough introduction—we’ll let the creators speak for themselves.

Taylor now owns 40 percent of the American acoustic market. Singer has delivered more than 200 customer cars. Growth like that doesn’t happen by accident. And yet you can’t totally plan it, either.

Rob Dickinson: It takes a nutjob, an individual. Just setting out on these goals… cannot be done by a committee. It can only be done by someone who’s got something in their brain that they just can’t shake off. That they’re convinced will be good.

Did you ask Kurt if he imagined Taylor would grow to this? I can probably guess his answer. There was never a destination to my idea. I just knew I was absolutely f***ing convinced it was a good idea. In as much as it would not kill me, or bankrupt me, or bankrupt all the people—my wife’s family—providing the money to get it off the ground. I was just convinced it would be OK.

Kurt, did you and Bob ever think deeply about growth? Or was it just… finding the next cool step?

Kurt Listug: The things that you do are the things that make sense to do. We’re dreaming all the time about things we want that could be great for the business, but it’s a matter of timing and resources. What do you get really amped up about, that you want to work on and pursue?

We grew the business to $150 million a year and basically self-funded. We started with $10,000, we reinvested, grew and grew. Looking back, it seems impossible, but that’s what we did.

You waited four years for one of Rob’s restorations. Why?

Kurt: I’m a 911 guy. I’ve had 11 Porsche 911s. I saw [Singer’s work] in the magazines and thought: Wow, that’s really incredible. The workmanship, the quality of the craftsmanship, the design.

Rob is… being an artist. I hoped [the car] would be as good as I wanted it to be. It really exceeded my expectations.

You told me that ordering one felt like a leap. That a project this complex could be worth the money and time.

Kurt: The car is reimagined, turned into something completely different. I like it when people do that, and really, any industry would just get stale and die without it.

With Andy being so creative, someone who can invent new guitar designs, that’s important to us—that’s who we want to be as a company. We want to make instruments that inspire people to create new music.

The music business and car business each run on an odd balance of tradition and new.

Kurt: With guitar companies, typically, when the founder gets old, they sell. The company is usually bought by financial people. They’re backing sales and marketing, and nobody’s in charge of design anymore.

The same old design becomes a legacy product. It doesn’t really advance, but it has to. You have to keep creating the new world, so to speak.

When I started the business, we couldn’t pay ourselves regularly for the first 12 years. I know with Rob, the company was basically financed early on by customers paying their deposits. He surrounded himself with people who were equally passionate. That’s how new things come into being.

Everyone knows these industries die if they don’t occasionally break out of the box. And yet they both push back on reinvention and call you nuts when you try.

Rob: It was just like, “We’ve got to build this and show our idea.” If you talk about it, people will just roll their eyes and say you’re f***ing bonkers.

That’s why we didn’t have any luck raising any money before we started Singer. We had to do it ourselves. “I don’t really understand. What do you mean, great quality? How are you going to make it look any different, any better?”

You start to get bored with those conversations quite quickly. I think the only way to do it is to build it. It comes through sheer passion or sheer insanity: I can’t stop thinking about this when I go to sleep, and I can’t stop thinking about it when I get up.

I love how artists and engineers, when they start a project, don’t always know where it will end up. They just know where to start.

Kurt: It’s getting an idea, an intuition, of the direction to head in.

Rob: Lots of people have good ideas. But lots of people can [move on, go] do something else. I just was unable to do that. To the extent that I pushed aside a reasonably rubbish rock-and-roll career for the sake of a car I had become obsessed with.

If everyone thinks something is fine as-is, how do you begin thinking about changing it? Is that process rooted in need? Problem-solving?

Andy Powers: All of the above. I have all these things, and none of them satisfy me—why not?

If you’re making something new through deeply considered choices, how do you prioritize that work process, not get overwhelmed by possibility?

Andy: What do I want it to be that it isn’t? That’s incentive No. 1. I don’t have what I want. I have no means to get it unless I build it.

Another part would be, maybe I have the ability to build something that nobody else has. Knowledge or tools or personal initiative. There’s also that simple question: Why not do this? With Southern California… in other places, the expectation is: Don’t do that, that’s not the way it’s done. Here, it’s: Oh, yes, do your thing, man. Hope you don’t get hurt.

Rob: The process isn’t work. I grew up in the Porsche community in England and was deeply within it for 5 to 10 years before I moved to America. Gaining opinions and attitudes, desires for what was best, what was average. The natural library builds up in the head as to what great can be.

So many great bits of new have compassed off California culture. Like how early hot-rodding evolved, couldn’t have grown the same anywhere else.

Andy: It’s the opportunity of a place and ability and desire all stacking together to go: Hey, this should be, and there’s nobody to tell me no. They’re not even paying attention.

Rob: And it is unavoidably entangled in ego. Wanting to express yourself. To be seen as the person who did something that needs to be done.

Ego can be productive.

Rob: If I’m brutally honest, I thought someone would do [what Singer does] before I did, and I wanted to get in there first.

I was thinking last night about where the great music has come from. The best rock-and-roll is audacious. Audacity is a product of ambition and ego, I think. Wanting to make your mark, to go: F*** it, I’ve done it, go tell me I’m wrong. The audacity to do that in a song! The Beatles had it flowing out of every pore.

Does that process look different when you’re rethinking someone else’s creation?

Andy: It does. You feel a great dose of respect, and you don’t want to upset that legacy. You already love what it is. In the case of a Porsche, there is a very emotional connection Porsche drivers have—with the legacy, the fenders, the sound, the feel.

Musicians have an attachment to their instrument that makes it behave almost like a living thing. It’s intimate—used as an expression of emotion, philosophy, aesthetic. You don’t want to do something that is totally irrelevant to that legacy, and yet, within context of it, you can make your changes.

One of the things that was a real departure in the history of acoustic guitars—we started bolting the neck on instead of doing woodworking joinery to glue those parts together. Mostly because [that change] makes it more serviceable. It just does a better job serving the musician over the life of the instrument.

Because guitars change shape over time. Wood moisture shifts, the neck has to be adjusted to play right.

Andy: Instead of a super-invasive and expensive repair job, this takes like 10 minutes. You take it apart, you put a different set of spacers in—it’s no different from, say, changing a car’s alignment.

Kurt: It’s all done with CNC [milling] equipment. Bob designed shims of different thicknesses… you can change, in thousandths of an inch, the angle of the body.

Before, you had to break the guitar apart to do that. It was decades to get to the point where he could do that. I knew he would eventually figure out how.

Andy: We went to great pains to make it look familiar. You want it to look and feel comfortable and respect the tradition of how the thing performs. More recently, we totally changed the internal architecture of an acoustic guitar.

Taylor calls it V-class bracing—this massive shift in how guitars are built.

Kurt: Un-freaking-believable. That’s a problem guitars have had forever: They’ll go out of tune once you go up the neck. Andy figured it out from surfing, looking at wave-forms. Sound is waveforms. He figured out it was really the guitar top fighting itself. He redesigned it. His V-class bracing, they play in tune all the way up the neck. That’s never been done. Ever.

Andy: It was a series of circumstances: Oh, I should take this influence from archtop guitars and mandolins, all these different instrument-building legacies, and I’ll combine those in this funny surfing context—that would give me a better architecture for how an acoustic guitar could work.

I could voice that and steer it in a lot of different directions. But the first course of business was, take this radically new idea that performs better and deliberately voice it so it is familiar to what a Taylor player already loves.

It’s not going to come out of left field—I’m going to hide it. When you play it, you’re going to instantly go: That is the sonic signature of a Taylor guitar. It’s all that I like, there’s just more there.

Why are we so compelled to make new from the old without losing the old?

Rob: [Our cars], in my humble opinion, they’re me thinking to myself: This idea can be even more fantastic than it already is.

I live in the past. I don’t like sci fi. I don’t like computers, really—I’m not very good with them. I live in a rose-tinted world of trips to France with my parents in the 1970s. From 1970 to 1985, we spent six weeks each year driving down to and around the south of France, sometimes into Spain.

You can imagine what I saw on the roads. The glamour and beauty, the birth of the appeal of the automobile to me, as an object of deep, dry-mouth desire. Those cars became my life.

I think it’s the same with music. My songs are very much a product of loving other people’s songs. I think our work on the 911 is very much a product of us loving the 911 and wanting to do our own thing.

That “dry-mouth desire” can be hard to share. Is it ever frustrating, trying to get a customer on board? “I can’t explain it, just trust me?”

Kurt: It’s not frustrating. It’s a challenge. You think about Rob, how he went about making a [964 have the nose of a] long-hood 911? What it takes to rebuild the whole thing to be able to do that? I texted the guys up there about the steering. I wondered what they’d done differently because it felt so good. I got back this answer: We’re using this and that and there was a 993 something-or-other and we designed our own bushing for this and that.

It’s just… they knew no bounds, to make it as good as they could.

A Porsche designer once told me that redesigning the 911 was half privilege, half curse. Everyone wants the car to get better, but no one wants it to change. It ties into this old saw in the car business, how what the customer wants and what they say they want don’t always jibe.

Andy: Ask your favorite band: We need a new single—can you make it different from the last one and make it sound just like the last one?

To me, it feels like a left-brain/right-brain exercise. You’re going to look at this thing as the sum of its parts, and at the same time, you’re going to see it as a cohesive whole: What do I like about it? What feels expressive?

Musicians are not doing their business with dollars and cents. They work with the currency of emotion. They’re trying to make sense of a wider world. That’s the language we need to think about if you’re going to disassemble this thing. Let’s say we want the guitar to have more empathy. What the heck does that turn into? What does it mean when a car has great road feel? What translates through a steering wheel? Technically, that’s a flaw, but why is it so dynamic? It feels like you’re engaging with a living thing. That’s something that needs to be preserved.

Those are all measurable, quantifiable things, but what they really turn into for a musician is: What can I do with this? How expressive can it be? I start disassembling them mentally. I want them to turn into the more subjective experience. Then, when I go back over to my holistic side, I want all of these components to still reflect and affirm each other. In other words, the guitar needs to sound the way it looks and look the way it feels.

That’s all fuzzy, personal stuff, but also real and universal.

Andy: It’s very real. If it looks a certain way, you want it to then feel that way when you pick it up. You want the sound that comes out of it to conjure up the same sensation.

So much of creativity orbits rules—new ones we make, old ones we break. Success can calcify that thinking. You don’t want to risk what you’ve built.

Kurt: I’ll give you an analogy of creativity versus not being creative, wanting to do the same thing over and over.

If you have financial people running, say, a record label, they’ll look at what’s been selling. They’ll say, I want you to sound like so-and-so. They’ll squash [an artist’s] creativity when that person really needs to develop their own voice, their own personality.

I think that’s just the nature of business types, because they’re used to looking at metrics like that. They’re not always able to discover something new, see something in it.

The car business is so similar.

Rob: I’m asked more and more what I think of the industry that perhaps we had a hand in inspiring. I’m going, “Why don’t you try and imagine what Singer might do next, rather than trying to copy what we’re doing now?”

I look at this new [Singer-like] Porsche 928 [restoration] that’s just come out. The entrepreneur behind this company found a car designer that he loved, a good car designer but with no passion for Porsche whatsoever. It’s like, let’s change it as much as possible for the sake of reimagining it. Rather than look at how the guys that were responsible for the 928 [thought], set about reimagining that.

Apparently, though, a lot of people love it. Which is fantastic. Who am I to say what the rules are?

Who are any of us?

Rob: It’s interesting how other people misinterpret why we’re around. Yes, I wanted to start a business. But what I really wanted was to make a name synonymous with doing something particularly, dare I say, unusual in the automotive sphere.

To get under the skin of a subject and understand it. Not just from a design aspect. From an industrial aspect, a social aspect.

The 911 is such a social thing. It’s bought for what it means, how it feels. And yet the business model is so metric-driven. Each new one must be faster, or they’ve failed.

Kurt: You stake 15 more horsepower every time you turn up with a new one. They have to give people a reason to buy it.

Right! As if a Porsche weren’t desirable already. The balance is so funny. If carmakers ask the customer what they want, they want a crash-proof ’69 Camaro with 3000 horsepower and a 5-pound curb weight. Does the music business have more latitude to listen there?

Kurt: The music business is really, really teeny compared to the car business. They don’t have the capability or the resources [to respond] to the public as quickly.

I admire what Porsche does. I think they’ve done a remarkable job with not wrecking the 911. They’re basically all the same animal, but the personalities are all a little bit different.

Does it ever feel limiting to work with only one instrument? One car? Evolving one object for most of your career?

Andy: I break them into categories. There’s always the projects that are going into production in six months. Some things, we can’t make in even 10 years. The players aren’t ready for it. We’re not ready to figure out how to make it.

To me, it’s exciting to work on all of them. Because you’re a product. Whatever a person makes is a snapshot of who they are right then—your experiences, influences, resources, inspiration at the moment. That might be the availability or lack of a certain material. It might be a musician asking for something. It might be a changing aesthetic that you can’t even put into words yet, but you know is there.

I’ll look at something and go, man, we just put everything into it. Now, two years later, how the heck are we going to do that again?

You can’t just double your efforts. You won’t get anything new or fresh out of that.

Rob: I think that Singer has an opportunity, maybe, to become a car manufacturer. Because of whatever we’ve done thus far. I’m slowly starting to put together the idea of what our first [ground-up] car will be.

In the past, I didn’t really scratch that itch, because I didn’t know what it was. I’m starting to get a better idea. I think it’s a journey through the past to get to something brand-new. That no one has ever seen before.

The question is, do we reimagine 911s for the rest of our lives? Or do we do other things with that notoriety that perhaps we’ve gotten? I don’t know.

With creating, what does it feel like when you realize you’ve gone…

Andy: Too far in the wrong direction?

It’s typically coming out of the struggle to bow to some market metric. Let’s say as a company, we want to make a new thing, and we understand that there’s a market and a price point we should look for. And that if we arguably delivered a set of features at that price, mathematically, you would have a certain number of customers.

The reality is, it rarely works that way. As I said, musicians aren’t doing their business with the currency of dollars and cents. Fortunately, we’ve never really gone that far. You tiptoe up to the line and go: Oh, that was the line, back away.

There was a psychologist, I think his name was Mendo. He did a lot of work back in the ’50s and ’60s trying to define creativity. The closest he ever got was saying that his essence of creativity was the formation of a connection between disassociated ideas.

You take two things that aren’t related, and you make some sort of connection between them, you’ve created something new.

What’s scarier—creating on a blank sheet with endless freedom, or inside fences?

Andy: Both are exciting and terrifying. Within an existing box, you don’t want to ruin it. You have a lineage, an expectation. A community of enthusiasts. You can all stand around this thing and agree on what it is.

Don’t disrupt that. That’d be like some kid stomping on your sandcastle. At the same time, [freedom] has its own pitfalls. Something entirely new—I might make one and go, “Well, this was exactly what I wanted,” and nobody else will agree. “You have what you wanted, now get back to making some we all like.”

Rob: A blank sheet is always scarier, but only if you don’t have an idea.

If you got an idea, it’s great. Approaching that blank canvas each morning. Even if you are embracing the traditional mores of popular music, which is built on repetition. If you’re challenging and you’re audacious, maybe your second chorus isn’t the same as the first chorus. Maybe there’s only one chorus. Imagine three verses and one chorus—f*** me!

When any band is trying to find new ways of doing things, these things are always experimented with. And you do find yourself coming back to this very satisfying sense, if something is really lovely, you want to hear it again.

It sounds so easy once you see someone do it. Making something new. Convincing people it’s worth it. And yet.

Kurt: I was the person who did all the sales, called on stores, and drove around the country. People working in guitar stores, or guitar players, they always want to see a new guitar. For ours, it was the [ease of] playability. Bob liked the thinner neck—he didn’t see any reason why we needed to have a [more traditional] bigger neck.

Everything in the business is problem-solving like that, even the creativity with marketing. When I had the money to start doing advertising, I didn’t want ads that looked like everybody else’s. It helped put the company on the map.

Really, anything you approach, you have to look at the problem and come up with a creative solution. Not just do what everyone else has done. Because who wants what everyone else has done? That already exists.

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I like imperfect things, which is why I’ll never own a Taylor guitar. They may sound great, but they have no apparent soul. Maybe that’s what the Singer owners who called to complain were getting at?

Sam, your writing is the best thing I read these days in the automotive sphere, and maybe anywhere. And what a brilliant melding of two of my favorite topics–911s and Taylor guitars. I don’t own a Singer, but I’ve owned five air-cooled 911s, currently an ’85 coupe. And one Taylor guitar, a special edition 814ce bought in 2005, that I’ll never be without. So for obvious reasons this piece, ahem, hit all the right note with me.

Lovely guitars and cars. I can only afford the guitar.

While wandering down the lawn at the Concours show, I stumbled into a conversation with a former owner of a now shuttered Lancia repair shop, still angrily spewing vitriol on all of the former techs she had the pleasure of firing, The techs never realized the honor and importance of their presence in relation to fine works of art. They would have been just as happy on the line at the Hyundai dealer. It resonated with memories of all of the Jazz school techs I never hired. Sure, they could write a Zappa real book, but couldn’t feel their way out of a wet paper bag! This is a passion project. The top 40 gig is at the airport Hilton.