Media | Articles

When combustion crimes call for internal investigation

One of the best parts of any project is the investigation into who did what to the hulk that has found its way into your garage. Some folks obsess over and pay a premium for service records that lay out a perfectly airtight timeline of what parts were tickled and when, but I’m not one of them, and I cannot pass up a sub-$1000 running motorcycle. Case in point: a 1998 Honda XR200 that I picked up during a short detour on a long trip.

The bike is for a friend, but he wanted me to go through it before he took possession. That meant tearing the poor thing down pretty far—not to bare frame, but awful close. What we knew: A ticking noise was emanating from the engine. It was also down on compression. Finally, and most disturbingly, at least two different types of silicone sealant were squeezing out from underneath the camshaft cover.

Thus began the investigation.

The cam cover of a ’98 XR200 can only be removed once the engine is out of the frame. I learned this by a failed attempt to remove the cover followed by a (ever-humbling) check of the shop manual. The engine-out service explained the loose chassis hardware we had noticed when we picked up the bike. Interestingly, none of the bolts were stripped: The person who last worked on this bike had a decent understanding of what was going on and access to decent tools. Both good signs.

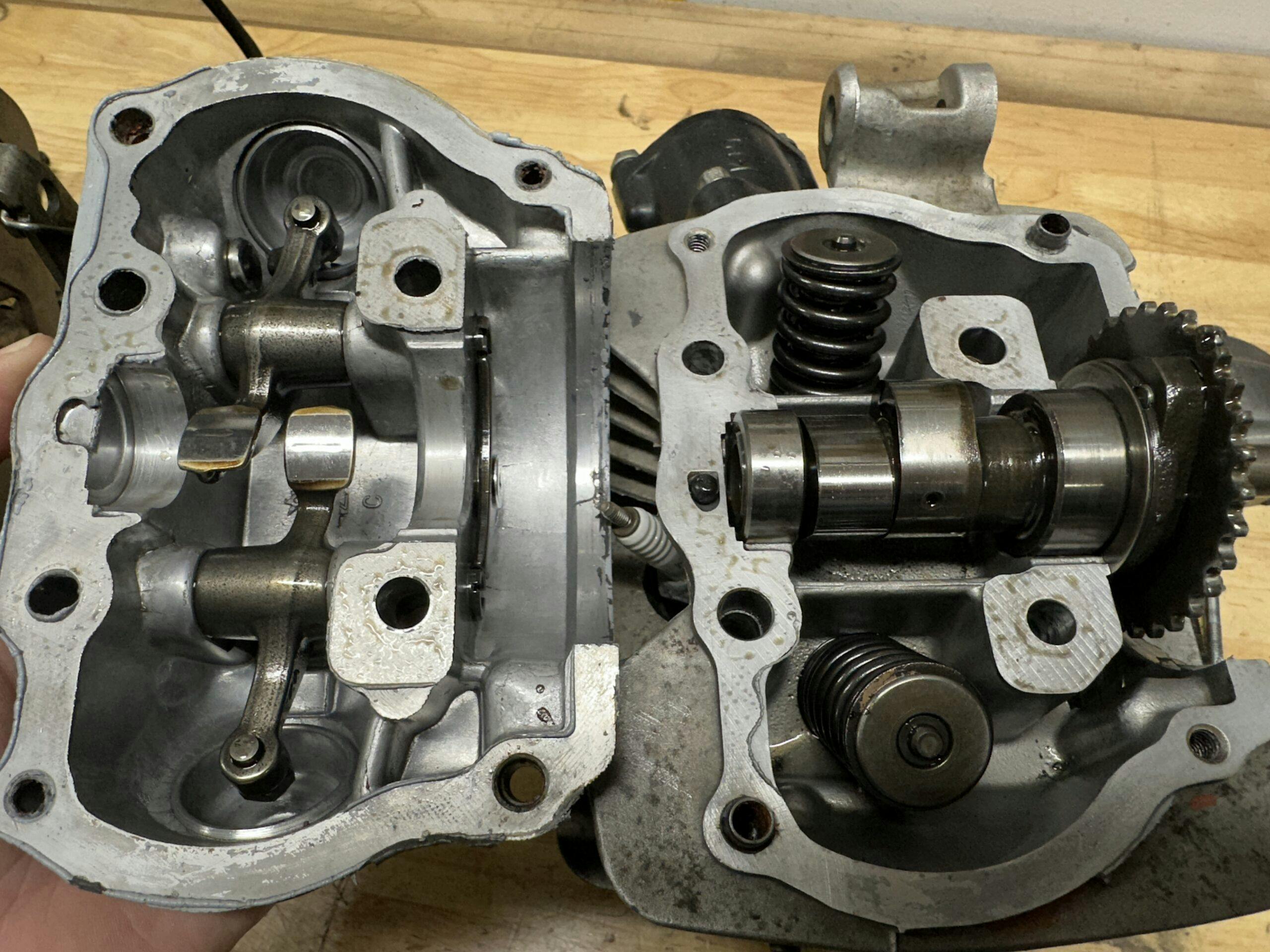

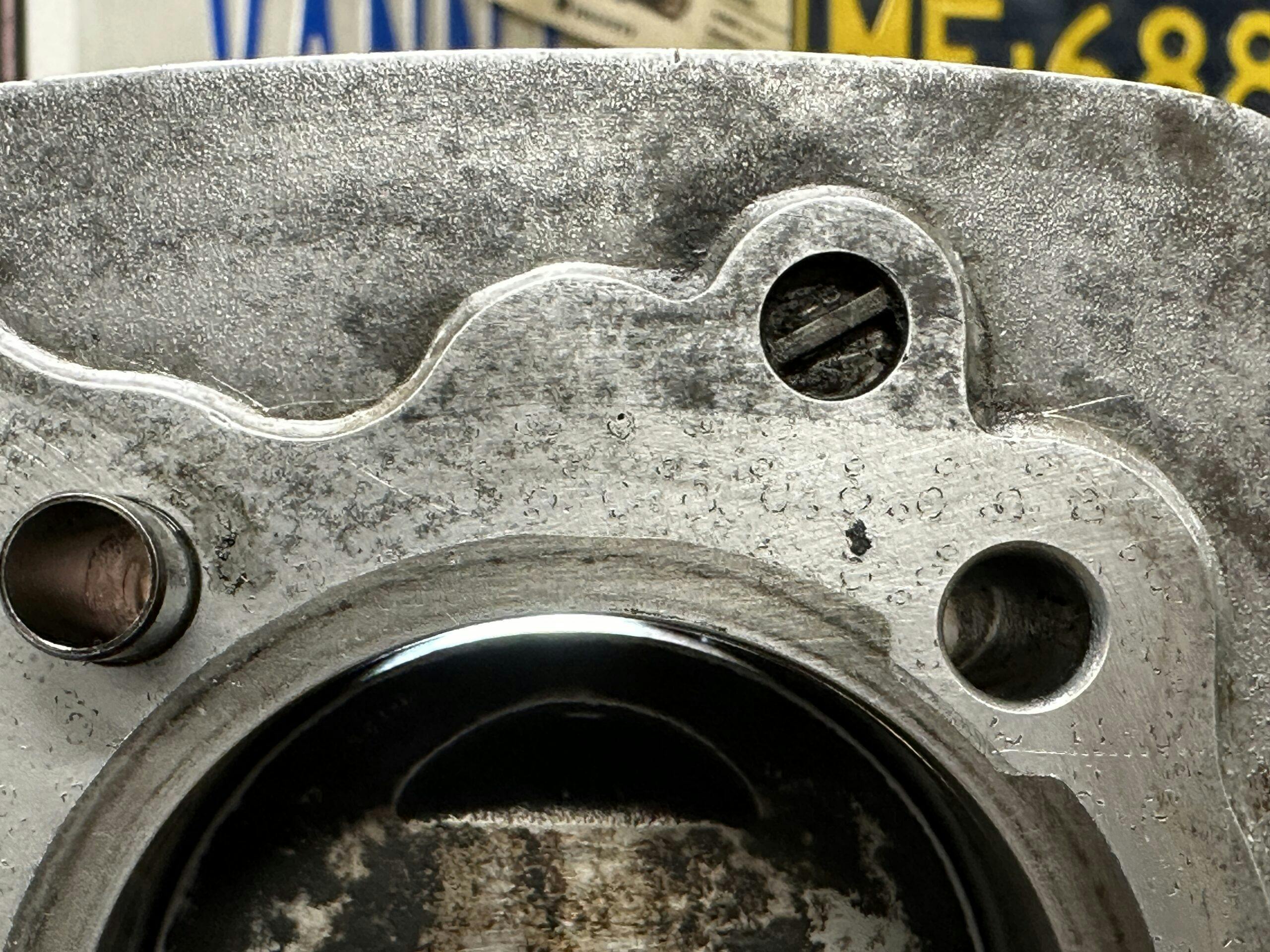

With the motor out of the frame, it was time to dig deeper. The camshaft and rocker arms were in great shape. No signs of valve or valve spring issues. Once the cylinder came off, the bad news came into focus. The cylinder and piston had experienced a type of torrid love affair that left both pieces scarred. The piston was marred, and the cylinder’s cross-section was more of an oval than a circle. That piston knocking around was likely the source of the tick, but I had yet to discover what the last person did or why they gave up. No signs of new gaskets or parts. Did the previous owner open this engine up and decide it wasn’t worth their time? That scenario would be ideal, but unlikely.

While discussing the workings of a rocker system over a cold one with fellow editor Nate Petroelje, a glimmer of shiny metal caught my eye. The automatic decompression shaft looked funny. Close inspection revealed that someone had used a grinder to remove the nub that acts on the rocker arm for the exhaust valve, the part that opens the exhaust valve slightly to make the engine easier to kickstart. The actions of the previous owner became clear: They had removed the engine, pulled the cam cover, ground off that nub thinking it was causing the tick, and reassembled everything only to find the tick was still there. Naturally, they then listed the bike on Marketplace.

The previous owner was sort of correct to suspect the decompression shaft, but the frequency of the noise had thrown them off-scent of the real problem. Having heard the bike run, even if only for 6 or 8 seconds, I knew the tick occurred at crankshaft speed, not camshaft speed. The cam spins at half speed relative to the crank, a difference that makes the process of diagnosing a noise a little easier if you can hone in on its tempo. The agricultural nature of these XR engines means they idle at just 800 rpm or so, which sounds very different than 400 rpm. In the case of this sad bike, that was the difference between 13 knocks a second and six knocks a second. Trouble here was that the piston seemed to be knocking around only during the power stroke, so the tick sounded like it was happening at half-engine speed—the same frequency as a noise in the valvetrain.

The previous owner went after the first thing they saw: the automatic decompression shaft. Was their decision due to lack of understanding, lack of care, or just laziness? We may never know, but what we do know is that this engine will get fixed correctly and will likely live a long and happy existence.

With any project, the goal of an investigation is not only to find out what is wrong with the machine, but also to understand what someone in the past has done to try and fix the problem—or to make it worse. Piecing together the history of what has failed and which parts aided in their own destruction will give you a better understanding of a system and of the life that particular machine lived prior to your ownership. Without knowing the full extent of the previous mechanic’s hackery, installing any new or refurbished parts is just rolling the dice.

The local damage to this Honda is bad, but generally my friend has a solid start on a project bike. We are two parts orders and a handful of evenings from a trail-ready machine. Well, we will also need a new-to-us cylinder and take a trip to the machine shop, but that is all relatively small potatoes for the sort of projects that come across my bench.

Repair and restoration can be as complicated or simple as you want, but if you want trustworthy results that you can be proud of, you must often be decidedly critical of just about every component you come in contact with. Asking questions like, “How did that get damaged?” and “What else would get hurt if that failed?” will soak up time and money, but you will also gain more knowledge and, in the end, success. Plus, who doesn’t love solving a good mystery?

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

As I currently have a 1999 XR200 taken apart on my workbench because of the previous owner’s shoddy rebuild, I can easily sympathize. In my case, the previous owner was unaware of break in oils or how to install a kickstart spring.

And just last night we cracked open the dash of my son’s new to him first truck (a 75 K10) to find the accumlation of nearly 50 years of electrical modifications that contributed to the brake lights blowing a fuse. It’s always a fun time figuring out the story of the machine, which is usually much more honest than the previous owner 🙂

My previous owner story isn’t really along the same lines, but it follows the same general theme. My 65 Impala had one fairly pristine looking rear quarter, and one with rot holes that were beyond repair, so I bought a rear quarter and replaced it. As I was finishing up the welding and buttoning up some patch work in the wheel wells, I found one rust spot in the wheel opening of the good quarter. I touched it with the grinder and got an instant puff of bondo. After a bit more grinding, I had discovered that the previous owner had accurately replicated the rotted away wheel opening detail with about a half inch thick layer of bondo. More investigation found more fine sculpting along the entire lower six inches of the quarter… off it came. That individual was one hell of a sculptor but not much of a body man in my book

Hey, Kyle, just grab some JB Weld and make that piston good as new!

At least it is a relatively easy fix.

Easy on that compression release cam. My KLX250S, was a dog to start cold. Mingled knowledge suggested too low compression at start. I replaced the cam release spring with a solid bike spoke alternate that eliminated the CR. Problem solved! Bike sold. I hope that spoke is hanging in there.