Media | Articles

Chevrolet took 52 years to make the Corvette mid-engine

Few ideas are genuinely new in the car industry by the time they reach production. Take Chevrolet’s much vaunted eighth-gen Corvette (C8), which was unveiled just three years ago and arguably created more media frenzy than any other Vette before it. The reason?

After nearly 70 years of front-engine, rear-drive evolution, Chevrolet had installed the car’s V-8 engine aft of the driver. But the idea was not new to Chevrolet; the company’s mid-engine ambitions had been brewing for half a century.

In 1968, Zora Arkus-Duntov, aka Mr. Corvette, wanted to take the model in a completely new direction. His interest in mid-engine configurations had started more than a decade before when, as Chevrolet’s director for high performance, he recognized that the best way to keep drivers cool in endurance races was to mount the engine behind them.

With the C3 Corvette launched in 1967, Arkus-Duntov built two prototypes—named XP-882 (for “experimental project”)—as an early vision of the C4. Radical in every way, the low-slung cars were 8 inches shorter and 5.8 inches wider than the C3, while shaving 700 pounds from the production car’s weight.

Though Arkus-Duntov had floated the mid-engine idea to Chevrolet years before with the CERV and Astro concepts, none of those vehicles flaunted the Corvette’s crossed flags. 1970’s XP concepts changed that. Still recognizable as Corvettes, each prototype’s V-8 engine was mounted transversely between the cockpit and rear axle. If it reached production, the recipe would transform not only the Corvette’s chassis dynamics but also how the car would be perceived by prospective buyers.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Maybe it was too much, too soon. John Z. DeLorean, Chevy’s general manager, rapidly canned the project on grounds of cost and complexity, but then made a remarkable volte-face after Ford announced its new association with De Tomaso and started to sell mid-engine Panteras in its U.S. dealerships. As a result, one Corvette prototype was hastily prepared for the 1970 New York Motor Show, where it received broad acclaim, with Motor Trend noting, “Chevrolet roared out of the sun with the throttle wide open and the wind shrieking, and watched their tracers stitch into the shining sides of the new De Tomaso.”

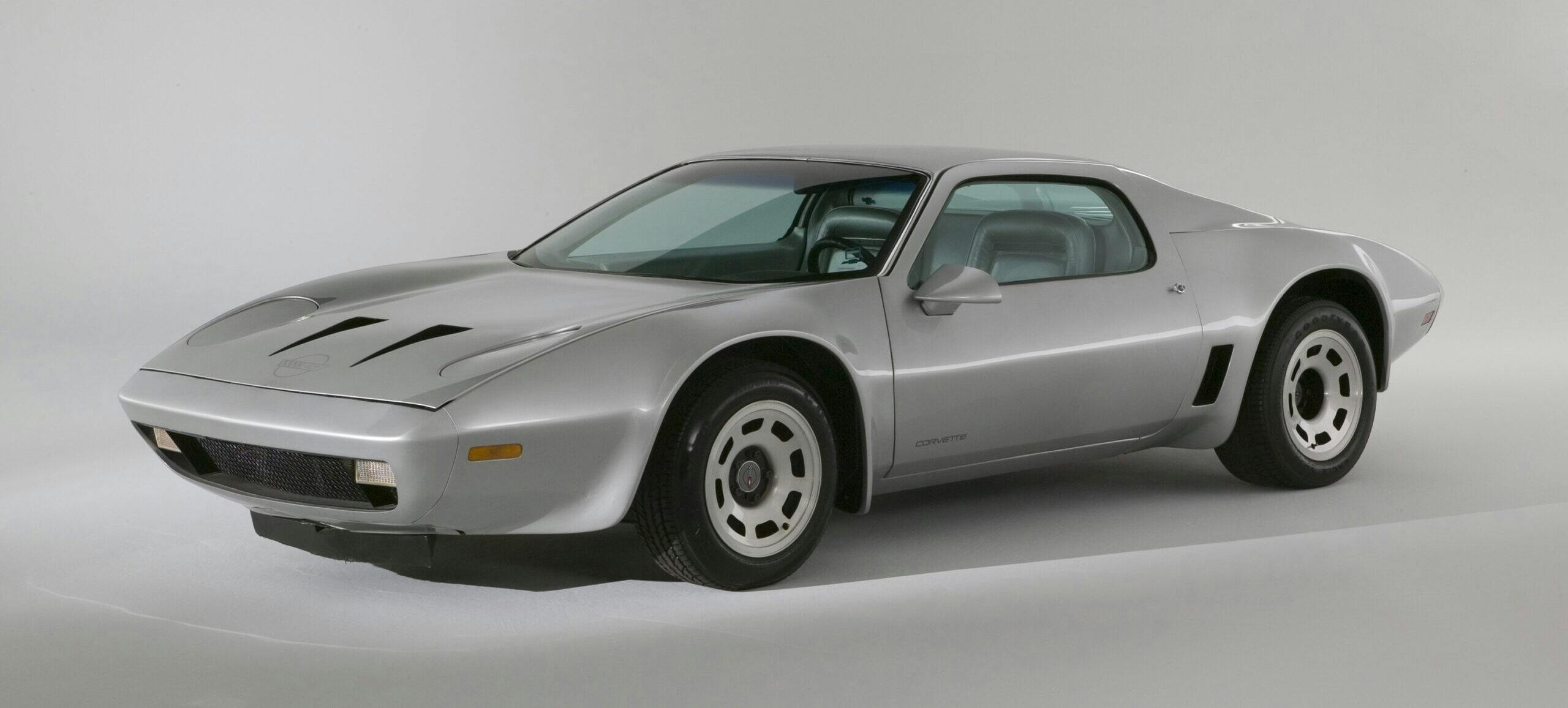

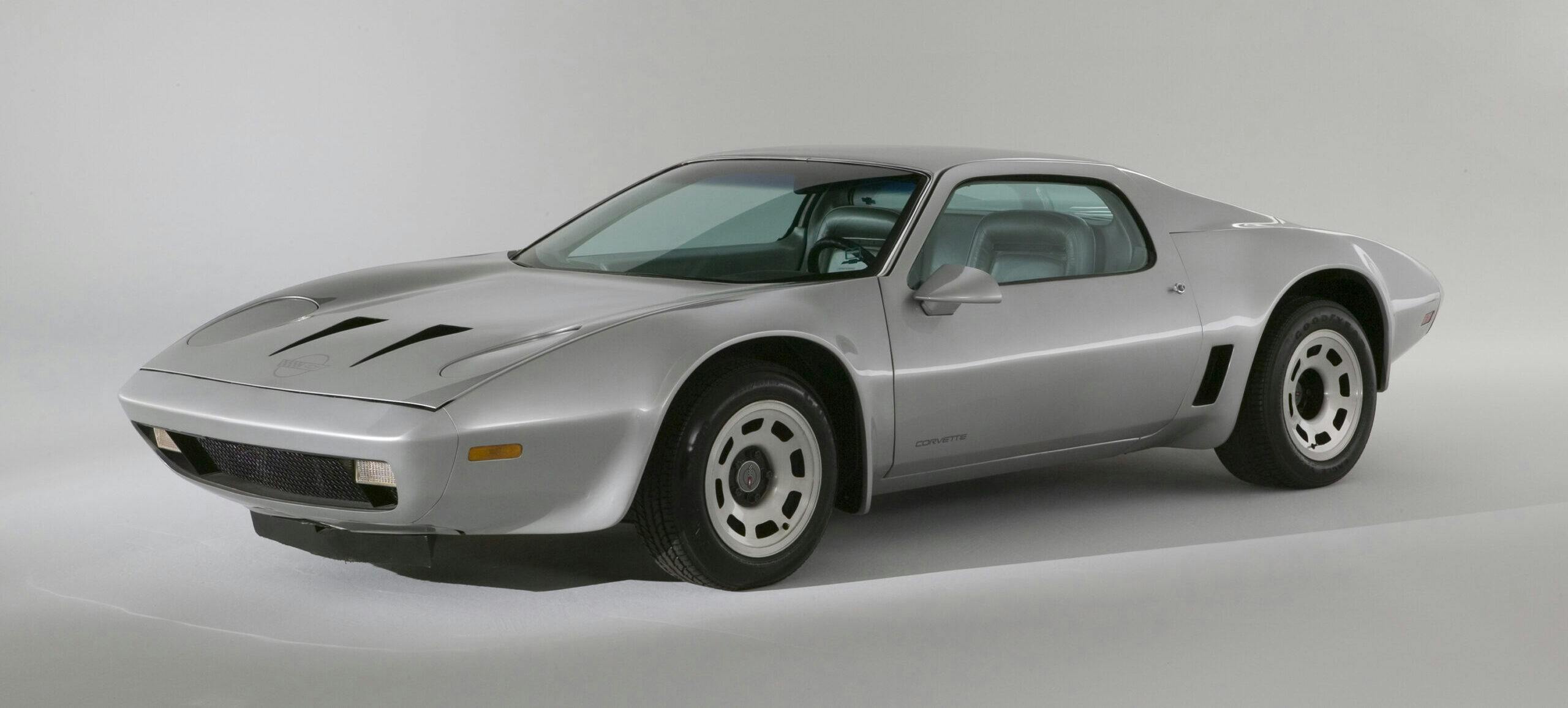

Buoyed by the bonhomie towards a potential mid-engine C4, Chevrolet went a stage further. The company had been busy with a Wankel rotary-engine program, the license for which it had recently paid $50 million. Taking XP-882 as a base platform, Chevrolet grafted together two twin-rotor motors to create a highly advanced, 420-horsepower engine. Renamed XP-895, the prototype now wore more rounded bodywork, flared wheel-arches, and NACA ducts in its bonnet.

Problem was that, being made from steel (versus fiberglass, like a production Corvette’s body), it weighed in at 3500 pounds, so the body was reformed in aluminum, giving a 40 percent weight reduction but adding massively to the would-be production costs.

All this came to naught when a combination of ever-tightening U.S. emissions regulations and an impending global fuel crisis impacted demand for performance cars. It also became clear that the C3’s production life was likely to be extended, despite the fact that it its performance had been well and truly neutered, at its worst delivering a paltry 165 hp from a 350-cubic-inch (5.7-liter) engine.

To top it all, the one man whose mid-engine vision for the Corvette had never waned—Zora Arkus-Duntov—finally threw in the towel, retiring from General Motors in 1975, frustrated that no real progress had been made in producing the concept to which he’d committed so much.

And the story may well have ended there, had it not been for yet another twist to the tale.

Barely a year after Arkus-Duntov left, mid-engine sports cars started to appear everywhere: Ferrari introduced the Dino, 308 GTB, and Boxer; Fiat was making hay with the X1/9; and Lamborghini had a new poster boy with its Countach.

GM’s design chief, Bill Mitchell, previously a mid-engine sceptic, couldn’t avoid the obvious trend and ordered a re-think of XP-895. The emissions-hungry rotary unit was pulled and replaced by a good ’ol 400-cubic-inch (6.6 liter) V-8, and the concept toured the show circuit as the Aerovette, with GM hinting that this could indeed be the new Corvette C4.

But once again fate had other plans. Arkus-Duntov’s replacement as the Corvette’s chief engineer, Dave McLellan, believed that such a major overhaul of the Vette’s basic design principles was a step too far. The cost of re-engineering the platform would have been considerable, and there was genuine concern about alienating traditional Vette buyers, who were becoming older and more focused on comfort. (Geez, they were even ordering automatic gearboxes on the C3!)

Fast forward nearly 40 years, however, and those buyers were dying out. Successive Corvette series (C4–C7) had successfully carried the torch for the brand, but by 2020 a new buyer was in the frame—someone younger and more susceptible to the charms of European sports cars, with their inherent sophistication and mid-engine configurations.

Small wonder that Chevrolet, with its C8, finally bit the bullet and put the cart before the horse.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Via Hagerty UK

The truth is GM and the Chevrolet division were not ready to build a mid engine earlier and had they we would not be celebrating 70 years of the name.

To be honest the Best thing that happened was Bob Lutz pushed back the C8 from being a C7. the extra time and the effort to get the new GM on one page made the new car a much better car as the development reaches back to around 07-08.

That extra time let them sort things out better and have more money to do it right vs just rushing it out and taking short cuts do to budget limitations. Most cars never get to enjoy a little over a decade of development.

GM also has one of the best teams in the Corvette group they have ever had. They are no longer that small group doing a two seater. They are a large staff that are some of the best not only at GM but the industry at suspensions etc. GM really has something to be proud of.

Under the leadership of Tadge I expect he and his team will be well remembered along with Mitchell and Zora. He did what the others Could not do. Also many of these same people are the same ones that made the C5-7 great.

The article does some skipping over the 2-rotor and 4-rotor cars. The Aerovette was the re-engine 4-rotor.

Corvette production ended in 2019;

now it’s just a Spaceley Sprocket;

The concepts were good looking or at the least interesting looking. I like the new car but I do wonder what would we could have today if mid engined happened earlier. Also would that have affected the Camaro positively as it has had to be a similar but held back car so it could not overshadow the Corvettes performance.

XP-895 & XP-882 looked much better vs the cars of the time (Ferrari 308, Pantera, etc.) than the C8 stingray looks vs it’s competitors today. I recently saw a C8 Stingray sitting next to a Ferrari F8 and another sitting next to a 911…it was (embarrassing) cheap-looking and noticeably a lesser car than both the Ferrari & Porsche. I also took noted the bit in the article that cited how they didn’t want to alienate their customers back then…fast forward to today, and the loyal customers that made the first 60-65 yrs possible mean next to nothing to GM/Chevy. And don’t get me started on the amateur-hour Z06 launch, special treatment for youtubers, etc.

Correction above: …I also noted…

Why do all of the past mid-engine Corvette prototypes and show cars look better than the C8?

You make it sound like Duntov quit in 1975. Wrong! GM had a mandatory retirement at age 65.