Media | Articles

In the Moment: Greens of summer

Welcome to a new weekly feature we’re calling In the Moment!

This all started in Slack, the messaging software we use for staff communication. Several weeks ago, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into our chat room.

In addition to being a lifelong student of automotive history, Smith drinks a lot of coffee. Each photo he dropped into the conversation was accompanied by a bit of caffeine-fueled explanation.

We liked these drops a lot, so we’re sharing one here each Thursday. Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

**

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Morning, everyone!

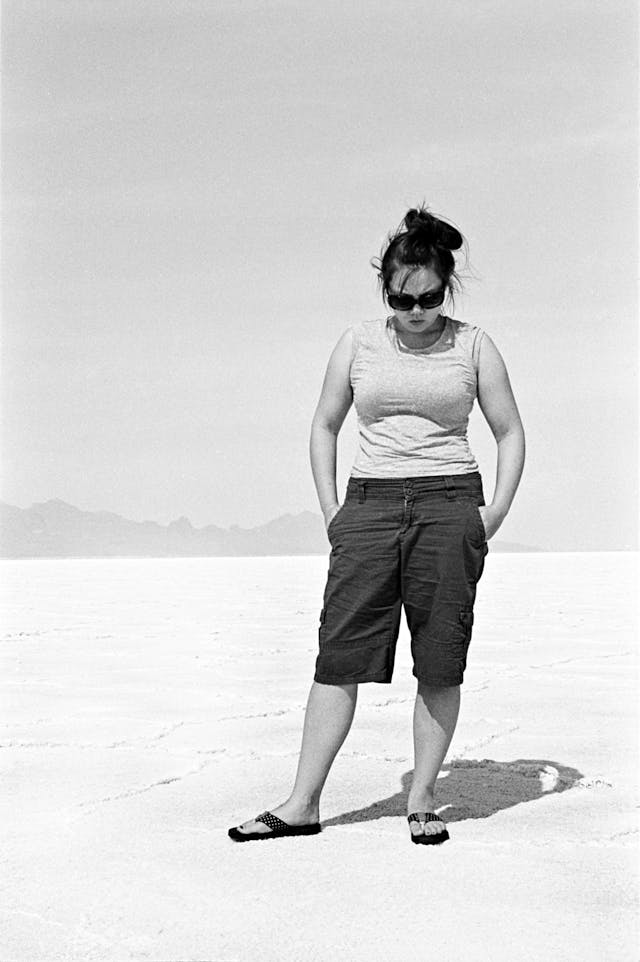

We’re going to change things up this week. Unlike our other images, that top shot isn’t from the Getty archive. It has never been published. This photo is quite personal, so this installment is a bit different.

Fair warning: This post is a long one.

I’m going to share a story. It will begin with cars but not stay there. Regardless, if reading sounds awful right now, I suggest this wonderful piece of mindless entertainment.

Want to stick around? Great! Let’s dive in.

**

Of Audis and Basins and Range(finders)

This is a scan of a 35-millimeter frame of slide film. It was taken with a 1970s Canon Canonet QL17 rangefinder.

The camera and photographer exposed this photograph in Northern California, near the town of Monterey, in a natural bowl in the mountains, in the pits of a track then known as Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca.

The image depicts a moment on the afternoon of Saturday, October 18, 2008. It shows a pit stop by the Audi factory team during an American Le Mans Series race. The car is one of just two Audi R10 TDIs—diesel Le Mans prototypes—campaigned in that race. This particular R10 finished first overall, but there was contact.

Those carbon panels are dirty. See the scrapes on the number board and the Michelin logo, the fraying vinyl wrap?

The team is doing a quick repair on the engine cover. A 29-year-old German driver named Lucas Luhr sits in the cockpit, waiting. His face is obscured by a mirror. His helmet livery contains multiple small Ls.

I happen to know a bit about this photographer. I know he wasn’t happy with this particular image. It’s a compromise, exposed for shadow and sun and spot on for neither.

I also know that, on the day of this photo, the shooter had a tri-tip sandwich for lunch.

Spoiler: The shooter was me.

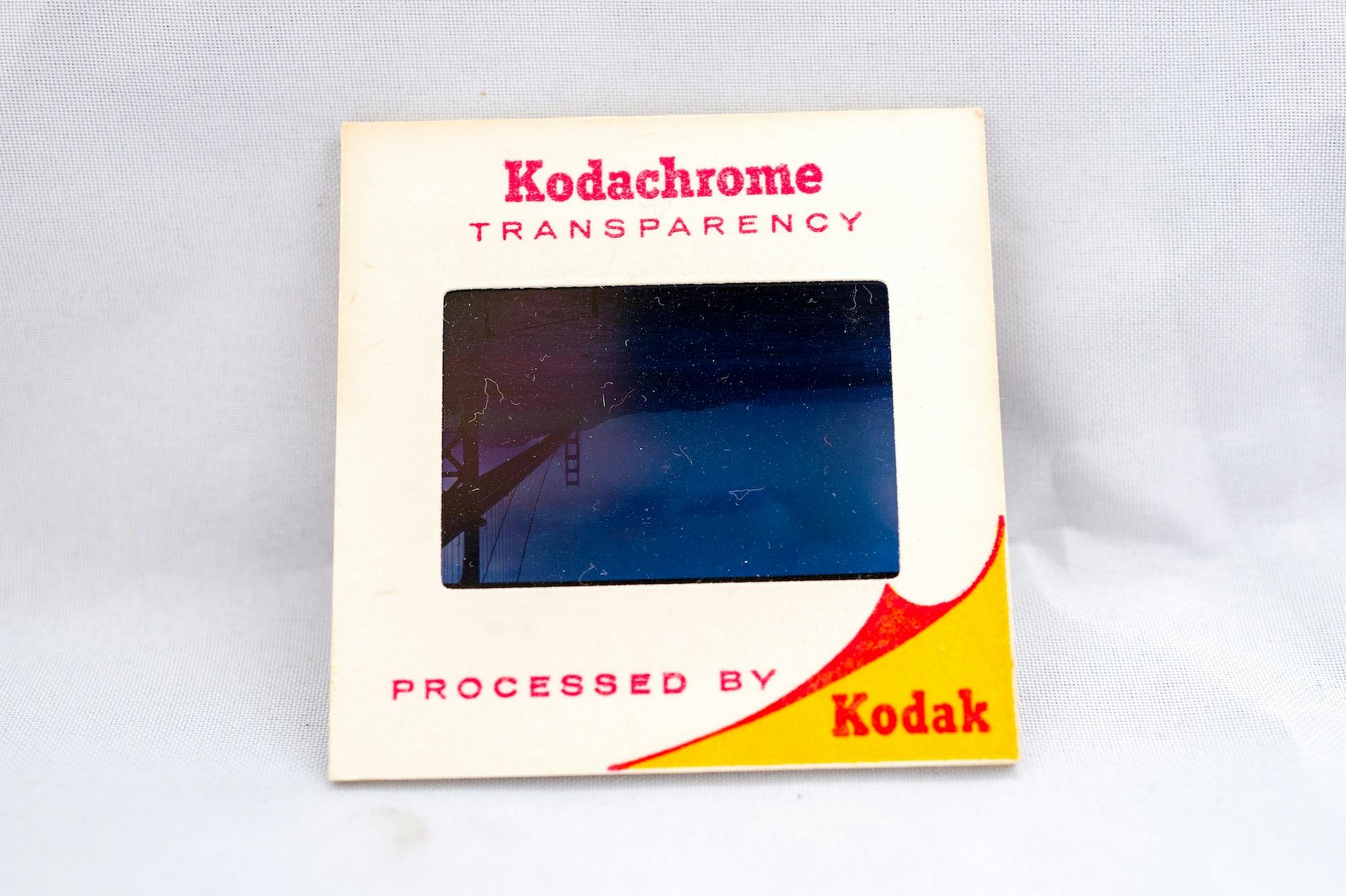

This is Kodachrome. The Paul Simon song! The most famous film in history. Again, I took this in October of 2008. I was living in Michigan but visiting Monterey for work. The slide was, for various reasons, not developed or scanned until 2010. At which point I lived in Northern California.

Those details may seem irrelevant. At the core, however, racing resembles photography: a series of decisions compassed by time and your own previous choices.

I began writing about this image as if it were any other In the Moment. Then I realized it was different.

Let’s back up.

***

Fourteen years can feel longer than it is. Ten years and 48 months ago, in the fall of 2008, my girlfriend and I lived in Michigan, in the college town of Ann Arbor. We had met two years prior while working at a now-defunct car magazine called Automobile. Adrienne was a copy editor. On January 15th, 2006, my first day, I stuck my head into her office and introduced myself. She had a master’s in journalism and a penchant for skirts. I was the newly minted assistant editor, 25 years old, a former Jaguar parts guy and one-time contender for the mantle of world’s slowest professional mechanic. Ten months later, we were dating.

To this day, I have no idea what she saw in me. All I knew was that she was smart and funny and looked great in those skirts. Plus, she laughed at my stupid jokes when I swung by to drop off page proofs. (Her, years later: “They weren’t that stupid. Mostly.”)

Salad days are always on a clock. In late ’08, Adrienne and I loaded a moving truck and left Michigan for the Bay Area. Mostly for me, so I could take another job. I told friends it was simply time for a change, and it was. At the core of that was an older truth—I had wanted to live in Northern California since childhood.

Wanting can seem as a good a reason as any, when you’re young.

Not that the change wasn’t practical. Writing about and testing new cars for a living had me in California half the year anyway. The state is thick with carmakers and race shops and fabricators, not to mention killer roads. If I was purposely minimizing anything, it was how the combined salaries of two journalists without family money would only go so far in the long run. But the long run seemed a long way off, as it always does.

Maybe I just assumed we’d find a way to climb. The copy editor had just landed a remote job with a firm in Chicago; she could live anywhere. My writing was beginning to get noticed and had won a few small awards. We had minimal expenses and zero debt. Optimistic, I went job hunting. After a few months, I accepted an editorial position at a small publishing house half an hour north of the Golden Gate Bridge.

That operation produced a few car magazines, including a fairly prominent Porsche title called Excellence. I was so dead-set on the end result that I took a significant pay cut for all this, having caved immediately when the hiring manager balked at matching my old salary. (Not that stupid. Mostly.)

By Christmas, we were established. A tiny apartment, with an attached and 0.75-car garage, near the city of San Rafael. The copy editor had agreed to marry me. I was a few months from turning 28. I could ride my old Honda CB400F to work on deserted back roads all year, then hike in the redwoods on weekends. The burritos were incredible, the outdoors even better. On top of that, my work-life balance was noticeably improved, job travel basically absent.

I remember when I realized it was all falling apart.

The Canonet, that film camera from the Audi shot, had come from eBay a year before. It cost 60 bucks shipped but arrived cleaned and adjusted, a bargain. A photography blog I enjoyed called the QL17 “the poor man’s Leica,” which is nice but also like calling a Volkswagen Beetle a poor man’s Porsche 911.

Still, people like Beetles. The QL17 was a 1970s rangefinder, this fun little clock of parallax. Rangefinders were obsolete 50 years ago, but their unique focus mechanism allows for neat lens construction. As for film, I shot digital regularly for work but was drawn to chemical photography by the abundance of cheap, high-quality used hardware. (Then as now, everyone wanted digital.) I stayed for the dynamic range and creamy shadows, where silicon had yet to catch up.

You get to pick how you drop your blood pressure. If only we could choose what lifts it.

Stress is insidious. It’s also quiet and patient. My selfish choices for a life in California meant, of course, that our money was tight. But we signed up for that, knew it going in. I had never met anyone as kind and thoughtful as Adrienne, and she was, to her credit, game for anything. The greater hurdle, one I feel uncomfortable sharing even now, is how the copy editor and I were perpetual strangers in a strange land.

It sounds silly and small but was one piece of a puzzle. We had dated for two years before moving to California and moving in together. Neither of us had previously lived with a significant other. We were each stupid and territorial about our space, as kids can be. Our families were thousands of miles away. We had maybe two friends locally, fellow transplants from back east, but they tended to socialize in ways that took money we didn’t have.

Californians don’t like to admit it, but the state’s social language is too often a closed door. We tried and repeatedly failed to meet new people and break out of the box of that apartment. Seasons passed. The firmware of our life shifted. I began to loathe my work and couldn’t explain why. Paradoxically, I also began to worry I wasn’t doing enough at that desk. I started staying late to get more done, though it made other problems worse.

I worked in a small office with four supervisors as my only coworkers. My desk sat solo in a converted lobby. Each morning, I would leave the house, where I felt alone, and go to work, where I felt even more alone.

Wanting to fix things but not knowing how, I aimed for the closest target. I churned more and more, gave longer hours, felt the sanity behind that churn slipping away. When the fighting began at home, I tried for patience and failed. When the arguments grew more regular, I simply made sure the house had enough cheap tequila. And when those fights began arriving twice a day—before work, after work, sometimes a fight about a fight about a fight . . .

Well, I had to decide between giving myself a drinking problem and finding other ways to cope. So I shot more film.

Those fights were asinine and potent, powered by stress. I was an expert at picking molehills to die on. I insisted on wrestling every single issue down to the ground, as if things like who drank all the juice actually mattered. When our cumulative blood pressure reached a peak, fights seven days a week, we discussed axing the wedding.

We were still undecided when, in the early fall of 2009, I lost my job.

The reason is immaterial. I felt better, years later, when my former manager told me he was sorry, that they had been wrong to let me go. Regardless, we were adrift. As a child, my parents drilled into me the importance of looking difficult moments—to say nothing of your own missteps—in the eye. Adrienne and I each took a deep breath, and then we went triage. We hadn’t been in California long enough to save enough to move back east. If we axed health insurance and every discretionary spend over five bucks, we figured, her meager salary would buy us a few months of rent and cheap noodles. A ticking clock while I looked for work.

So that was what we did. I hustled. In the background, a remarkable thing happened. The arguments stopped. We somehow remembered that we liked each other. Stability had gone out the window, but something else had come back in.

It seemed frivolous, but I kept taking pictures.

We could afford it, barely, but that doesn’t mean we could afford it. The months that followed were a heavy squeeze, even as I found work writing. But we did have those two local friends from back east. One was a former coworker at Automobile, Jason Cammisa, who now works for this company. (You may know him from YouTube; he stood up in my wedding.) The other friend, my pal Michael Chaffee, lived across the Golden Gate, in San Francisco.

Each helped whenever they could. Chaf, in particular, was like a brother to me. We had met, years before, through track days and old-BMW ownership, back when things like E30 M3s were cheap. Just as important, he had in his apartment a scanner and the chemicals to develop black-and-white film.

“There’s Ilford HP5 in the freezer,” he said, one day. “Yours if you want.” Because he bought the film in bulk, he passed it to me at cost or free, three bucks a roll at most. After I’d run a few through the Canonet, I’d shove the canisters into my jacket pocket, fire up the Honda, and bop over the bridge to Chaf’s apartment.

I was making something. It helped.

No photographer who has made their living with film will romanticize the hours lost to the medium’s logistics. My friend Regis Lefebure has long shot motorsport professionally. “Sure, get romantic and artsy,” he once told me. “You didn’t have to fight the stuff on the road, praying you got the shot. Just take a RAW file, crank up the grain, you’re close enough.”

I’m not a professional photographer. Nor am I a professional mechanic or musician. And yet I take photographs, I rebuild cars, I play instruments. We all have reasons for doing what we do when we’re not getting paid.

***

That second year in California, I made a choice. I consciously changed how I looked at relationships, my wants, and, most important, other people. I built a freelance career that eventually saw me working regularly for places like Wired, the New York Times, Esquire, and Car and Driver. Adrienne and I got married. We acknowledged that we couldn’t afford to live and raise a family anywhere in California that made sense for my job, and we began to pave a road out.

That freelancing eventually led to a position as executive editor at Road & Track, where the team I helped lead was nominated for a National Magazine Award, a car-magazine first. That job led to this one, at Hagerty. I am now lucky enough to work with some of the smartest and kindest people I’ve known.

Which brings us to now. And Kodachrome.

That name fades in meaning with every passing year. It is a brand but also a patented chemical process and a delicate brickwork of saturated dye layers. It was first sold as a color slide film in 1936. Maybe you know that Simon song?

Nice bright colors, he sings.

Sometimes. It’s apparently easier if you’re Steve McCurry. What the film gave amateurs was in my eyes much better, a more subdued and old-world palette, almost cinematic. Plus the kind of crackly, projectable detail—3.5 centimeters of virtually unbelievable resolution—that was, with slide film, once the reason for the season.

Production lasted 74 years. The formula saw changes, but Kodachrome in 1936 was basically Kodachrome in 2009. By the time that last year rolled around, Kodak had narrowed its offerings to just one speed, ISO 64, and one size, 35-millimeter. There was also in all the world just one lab certified for processing—Dwayne’s Photo, in Parsons, Kansas.

Even by the wacky standards of color-positive film, Kodachrome development is odd. The process was designed to produce a perennially stable image of high clarity, and it succeeded. Most color film fades after a few decades, but evidence suggests Kodachrome can hold fast for at least a century. The tradeoff was a painfully narrow exposure window and a recipe so brutally unforgiving that Dwayne’s famously kept a degreed chemist on staff solely to analyze film solutions.

Get the light and cook right, though? Colors that hit like a warm blanket. Or a Monterey summer.

Kodak stopped making this stuff in 2009. Still, the people at Dwayne’s, those heroes, they knew it was still out there. They vowed to keep going as long as they could, as long as Kodak kept shipping the required chemicals. Over the next year, thousands of rolls arrived in Parsons, from all over the world.

My Laguna shot was in there.

***

In early 2010, a few months after our life in California changed, I found in my desk a few forgotten canisters of K64, exposed but undeveloped. They were unlabeled, no dates or subject notes on the cans.

Kodak had already killed the film. Dwayne’s would continue accepting exposures until the end of the year, but I didn’t know that then. I looked up the processing cost online. Three rolls was roughly equivalent to a nice dinner for two, even before shipping to Kansas.

We were still broke. I had no idea what was on that film and absolutely no business paying for expensive and tiny pictures round-tripped from some Midwest chemistry mecca. I grew determined anyway. A door was about to close, and once it did, whatever was in those film cans would be locked in there forever.

We scrimped further. From the cheap noodles to the nearly free noodles. Weeks later, when I had saved enough, I sent the chromes off. More weeks went by. When the film returned, I rode down to Chaf’s place.

In the end, the Laguna photo was the last to hit the scanner. A decent shot, but nothing special. With that old Kodachrome trick, though: Colors as I remember them, if not as they really were.

In late 2008, I had flown to Northern California for work. I took a weekend off to walk around that idyllic track, shooting the race for fun. A few days after I flew home, we loaded a moving truck and aimed west.

Adrienne and I now live in Tennessee. We have two fun and quirky little girls in elementary school and an old house where the stairs creak at night and I occasionally have to tell those girls to not draw ponies in toothpaste on the bathroom mirror. When we left San Rafael in 2011, it was the responsible choice, heading east to stay with relatives for a bit, to recover financially. In the nine years after, we lived in Detroit, Chicago, Ann Arbor again, Seattle, and, finally, Knoxville.

Each of those moves was driven by family and work and nothing like childish want. I could tell you I don’t miss the West Coast, but I’d be lying. Still, that was then and this is now, and we are, to my only occasional surprise, happy.

This image is then, too. It makes me think of the guy behind the camera and what he wanted. A life that was so close to, but also so very far from, the one he came to need.

Have a good day, guys. And thank you, as always, for reading.

—Sam

**

If you have a minute, click on any of the above film photos to view them in our site’s “lightbox” zoom. The depth in the Kodachrome and Ilford shots in particular is fantastic —Ed.

Long story never finished.

I just wanted to comment on the Audi. That was one amazing race car. It had so much torque off the turns it was amazing.

But the car was so quiet. I could hear the air over the wing as it passed. Also if it hit the rumble strips you could hear it over the car. That was one car that had to be seen in person to understand.

Yeah, the diesels were bonkers! P1 cars were spaceships to begin with, but those things were something else. When they came by alone, away from the pack, you could hear everything. Tire scrub, even, just this little shoop-shoop-shoop noise on turn-in. I once heard what sounded an awful lot like brake-pad groan (Turn 5, Road America).

The story made those sounds carry a different weight. You hear similar stuff in Formula E, but it’s from the whole field and doesn’t seem special. It’s also drowned out by bodywork clatter.

Audi’s domination eventually grew tiresome, but early on? Just so great to watch.

“Colors as I remember them, if not what they really were.”

That’s life in a nutshell right there, isn’t it?

Older I get, Pete, the more I realize how grateful I am for the memory filter. So many sunny days that weren’t. I think I like them better this way.

Might need a cigarette after that one. Thanks, as always. Top notch stuff.

I grew up shooting film but I think we just called it “photography” because that’s what is was, a process. In high school my parents just watched as I converted our spare bathroom to darkroom. Tool of choice in the late 70’s was a Nikon FM, and the corner drug store in our small town had had a spread 35mm stock from Kodak, Ilford and maybe a few oddballs. Always aspired to shooting 120 roll film with a Hasselblad but those cameras with a lens were the price of a new car… I too shared an eBay moment decades later but before the recent film resurgence. A Hasselblad ripe for the picking at less than the cost of family room sofa, with two fungus free lens! As the selfie world turns, it’s the best decompression ever to calculate an exposure, look at the world backwards and then rolling those negatives through the scanner.

This article is a gem in so many ways, made my day.

I have a ziploc bag of undeveloped 35mm film rolls. Some are mine, some belonged to strangers. I remain hesitant to develop them. To see a frozen moment from long ago, to know that nothing has changed but me, might not be a comfort. I think I will keep them in their current state – memories not forgotten, just ignored. All memories belong to the past. Some are best left there. I know I was there for the ones I shot, and that is enough for me. Thanks, Sam.

Awesome Sam!!

I consider Sam Smith a friend as he has personally spent time in my home and working on my 2002 in my garage when he lived in St.Louis while attending SLU. I enjoyed him then and I enjoy reading his work still. I regret when the article ends, but truly regret that Sam and I have drifted apart through the past 20 years. I still have the ’02 he tuned the fuel injection on in a dark unlight cold garage! Great guy, great writer, even better driver, and now sounds like a great father and husband!

Aw, Terry! You’re so kind! Been way too long. I’m so glad you still have the car! I remember that cold garage like it was yesterday…

What a fabulous piece. I’ve only been reading you for a few years, but it’s been a real pleasure to follow along as your capabilities and range expand. This piece was not funny and wasn’t at all about cars, and was great

This is a wonderful article, so forthright Sam Smith, warts and all. There are aspects which probably parallel parts of my own life in small ways – likely a lot of other readers too. My first serious 35 mm camera was a Ricoh SureShot 2.4, through which countless rolls of Tri-X passed, all developed and printed my me starting when I was about 15. I still shoot B&W film on a 40-year old Nikon FE and used to shoot a lot of GAF 400 slide film as I could process it myself. I really liked the colour saturation, and certainly the film speed, better than Kodachrome, although the attraction was that I could process it myself. The relationship of those Kodachrome images to the Audi racing cars was well worth the wait; history always permits a better understanding.

Please keep writing more Mr. Smith. I’ve read your stuff for many years and always look for it and enjoy it.

Meanwhile, what (I think) was missing from the story was how and from whom you borrowed a Leica M3 with a 35 mm f2 Summicron to make some of those images; even in 2009, M3’s, (the cameras as well as the cars), weren’t exactly the sort of device that one handed over to a friend with a casual admonition to “Take care of it.”

First off, thank you! And thanks to everyone else, as well—all of you have said such kind things. It’s humbling to read. I’m so glad this resonated in any way. It took a lot to write; it took a train, as the line goes, to hit save and line it up for publishing.

Leica loan: That’s Chaffee again. The M3 from most of those shots was his, an early double-stroke. (As I said, he’s like a brother to me.) I also borrowed another, later one from a relative in Detroit. They’re such marvelous cameras. Just every bit what they’re supposed to be. Was a privilege to gun it for a bit.

Sam- I’ll say wow, just wow.

Thanks

Amazing story Mr. Smith and kudos for opening up about your life a bit. I was barely born when that R15 TDI pic was taken and I think that single pic has made me fall in love with that car. These are the kind of automotive stories that you can literally make a movie about.

Great writing, Sam! Though your article is not about your mother, her picture brought back many fond memories. My best friend.

Thank you, Jackie! We all miss her so much, and I think about her every day. I’m still learning how large of a dent she made in the lives of so many. So much I wish I’d known, while she was still around, so much I wish we could have talked about that’s happened since…

I find it interesting that you have the same observation of the state’s social language as I did. I remember sitting around discussing it with co-workers, All of them non-native Californians. Still, given that winning lottery ticket, I’d be back there in a minute.

Sam-

As one of those guys who kept R&T + C&D alive with 50 years worth of subscriptions, I have always enjoyed your work. Next time you are banging around Northern California you can stick your head under the hood of my kid’s 2002tii. He would love to show it off to you. I suckered him into by having an 02 when I married his mother.