Media | Articles

The genius of Bugatti, the madness of Bugatti

Across the digital world, most published content is designed for quick consumption. Still, deeper stories have a place—to share the breadth of an experience, explore a corner of history, or ponder a question that truly engages the goopy mass between your ears.

Pour your beverage of choice and join us now for a story from our Great Reads project. Let us know what you think in the comments or by email: tips@hagerty.com

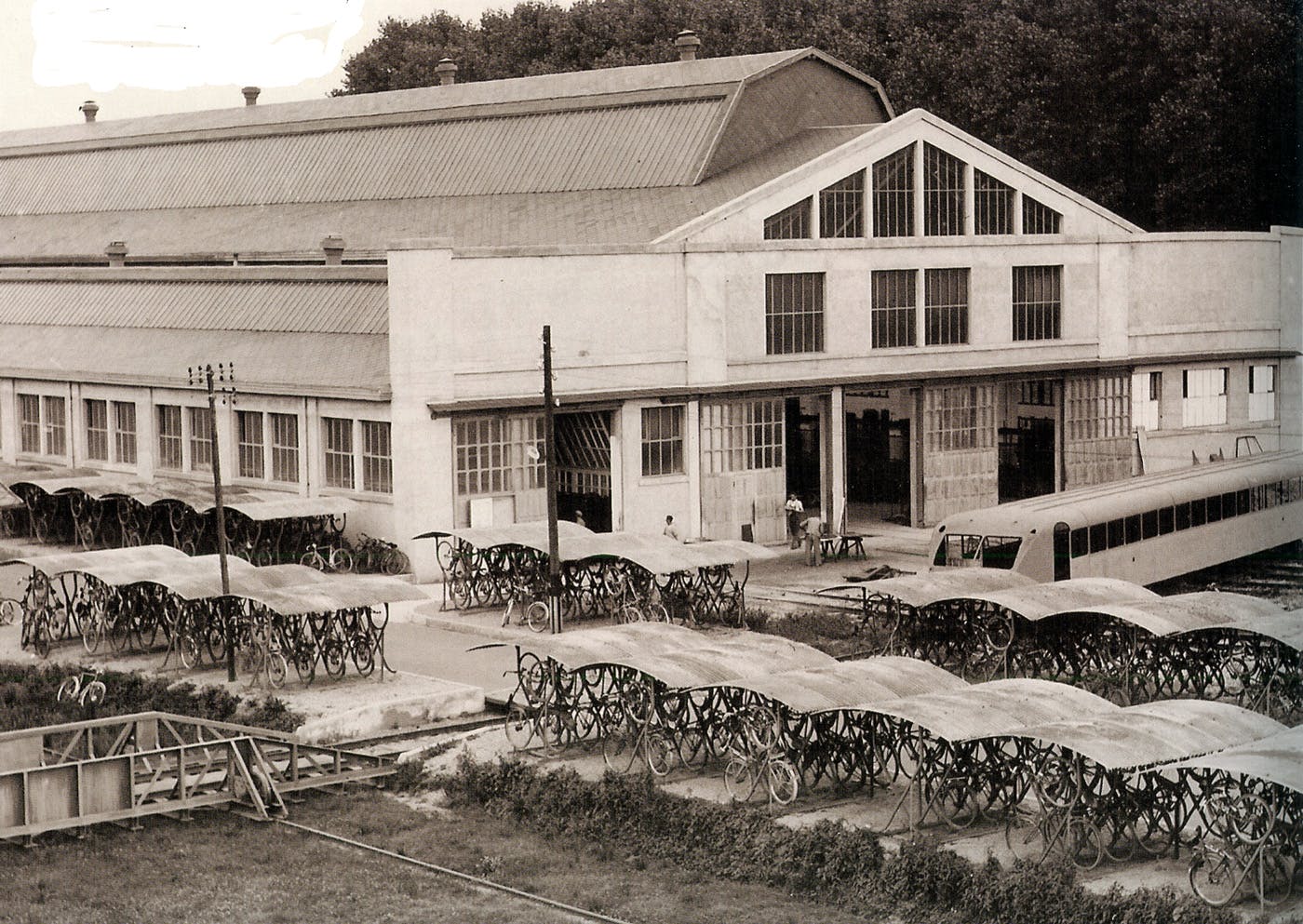

The man came from Italy but loved French culture. He lived in France, he identified as French, and many of his race cars were French blue, the national racing color. In the 1920s and 1930s, he built those cars in the town of Molsheim, near Strasbourg, in the region of Alsace-Lorraine.

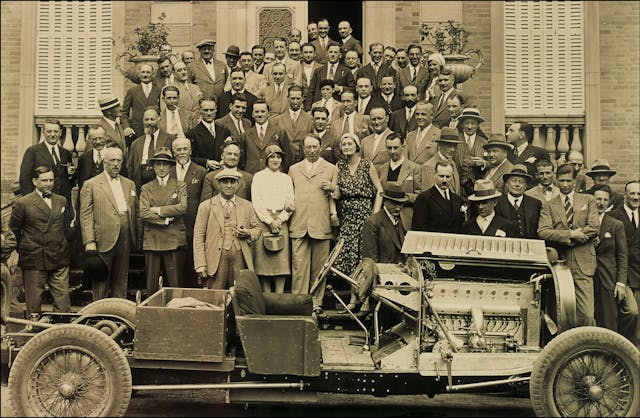

That factory sat sat very close to a mansion, what the French call a château. The man used it to house clients. Alsace-Lorraine, for its part, had not always been French; the area was seized by Germany in 1871 and only returned to France in the wake of World War I.

A century after that return, the Italian Frenchman’s mansion is owned by a German car company born in the wake of that war. That firm continues to build fast cars a few steps from the house and under the old name, but the new machines are nothing like the old. Even though they are, in a certain sense, remarkably similar.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

This is Ettore Bugatti. You discuss the man, things get complicated.

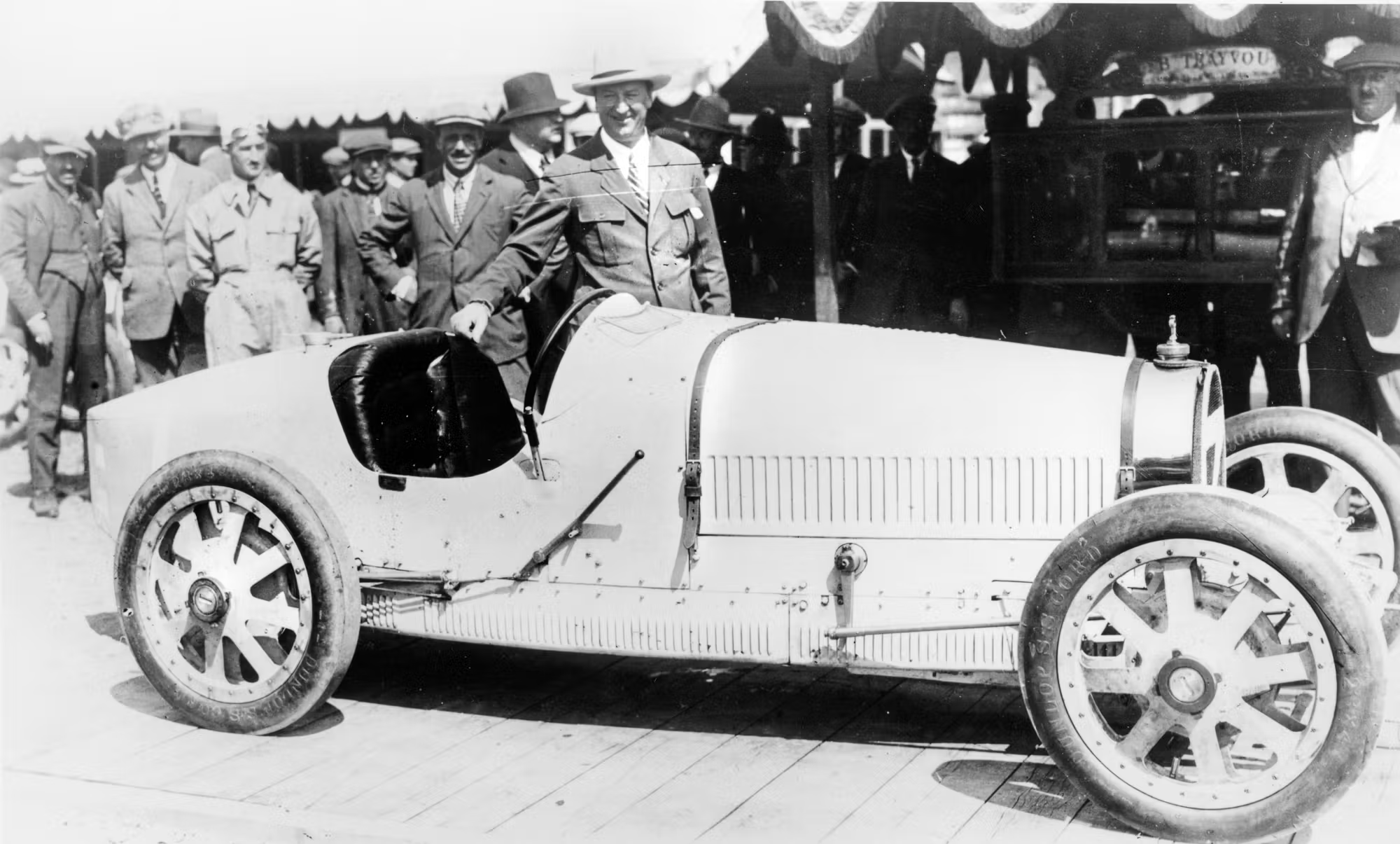

Ettore Isodoro Arco Bugatti was born in Milan, in 1881, into a family of artists. When he was young, he raced motorized tricycles; by 19, he had designed and built his first car. He was honored for that work, albeit not universally, at the period equivalent of an international auto show. Not yet in his twenties, this erudite, well-dressed individual was already known for being haughty and divisive.

Years later, followers would call him Le Patron: the patron. A supporter of art.

Bugatti had always built things, but he gained real fame in the 1920s, when his efforts had enough funding and momentum to go big. Sometimes literally. One of his largest efforts was the 1927 – 1933 Bugatti Royale, a 21-foot, 12.7-liter, 7000-pound, straight-eight luxury car aimed at royalty. Its engine held 24 quarts of lubricating oil and required 11 gallons of oil as coolant.

Only seven Royales were made, largely because the model was launched smack into a worldwide depression. On the other end of the scale was Bugatti’s work in grand-prix racing, where his cars were, for a few short years, kings.

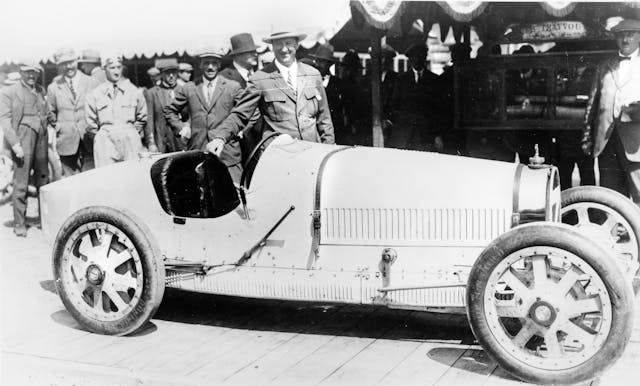

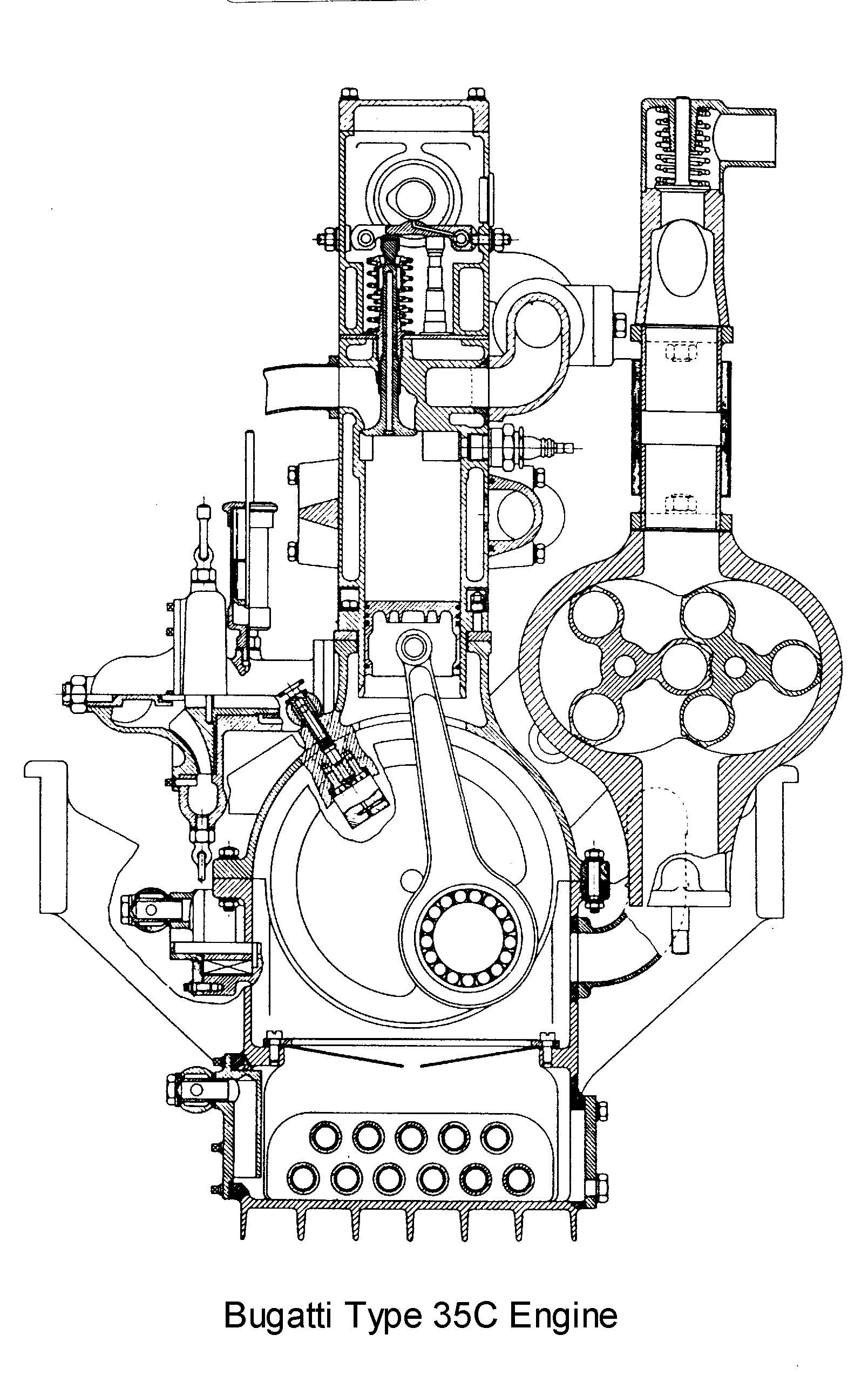

Grand-prix racing was the precursor to Formula 1. In 1920, many machines in the sport resembled large beetles. Like the road cars of the era, they were tall and bulky. By 1925, those racing cars had grown slimmer and more hunkered, shrunken into tapered darts. Into that competition Bugatti released the Type 35, a waspish, boattailed weapon designed with fierce fitness for purpose.

This was, remember, an era where new cars wore such little thought for safety that minor crashes often turned drivers to chunky marinara. Motorsport was more than art than science. Race engines were often absurdly powerful—four or five times above a period road car of similar displacement—but chassis, tire, and brake technology had not kept up. Most racing cars had weak spots, jobs they didn’t do well.

The T35 was fast and balanced, almost absurdly well-rounded. It began winning early. Then it won even more. Bugatti figured out how to productionize the car, and then he figured out how to make the wealthy public want it. His small factory built more than 300 Type 35s in an age when “mass production” of a world-beating race car might mean five or ten examples.

Between 1924 and 1930, Bugatti says, T35s won more than 2000 races around the world. English motorsport historian Laurence Pomeroy believed more than 1000 of those wins happened in ’24 and ’25 alone. The car won the Targa Florio five times in a row. It was so utterly dominant that it became, for a time, the only answer to a certain question.

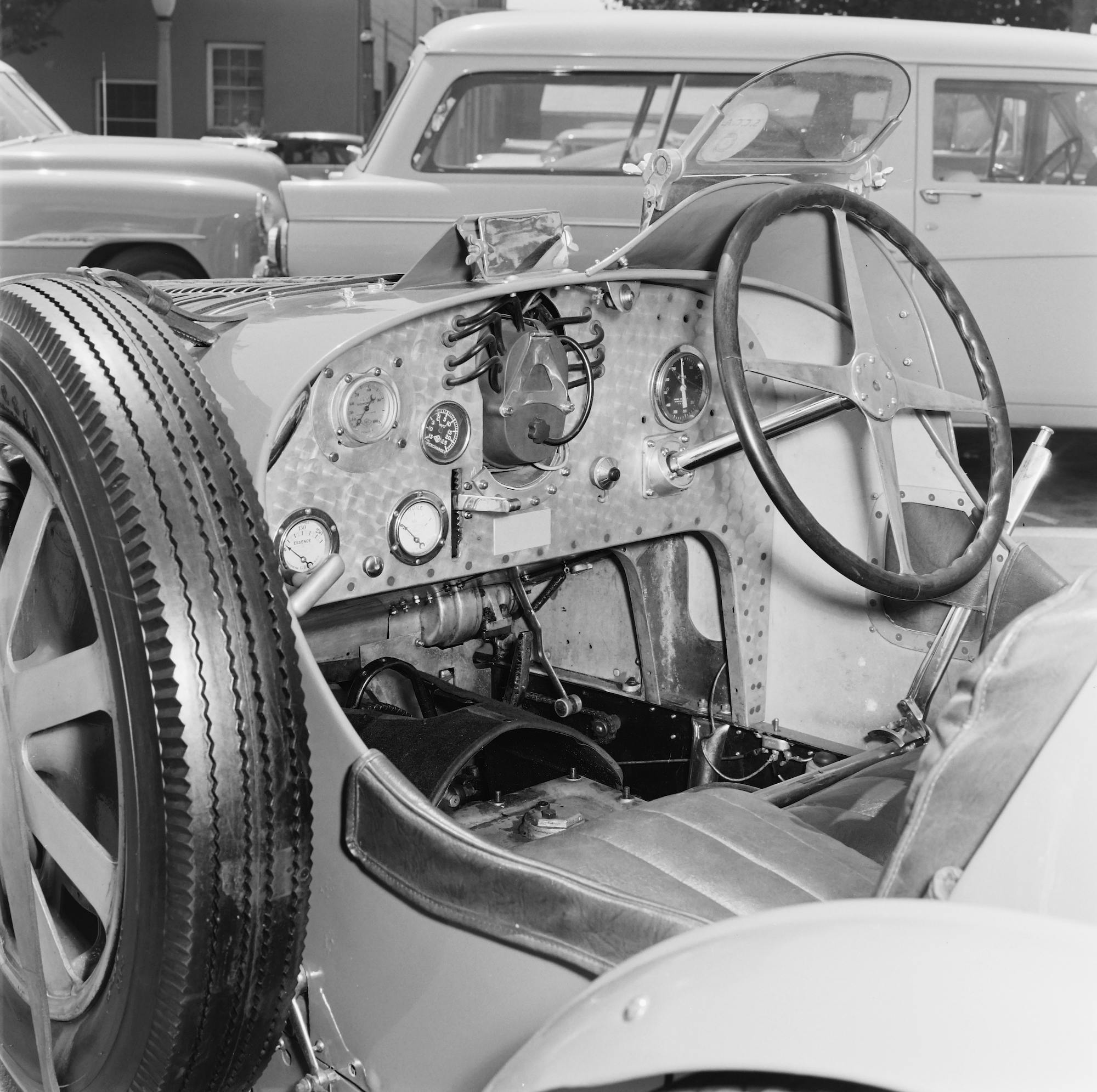

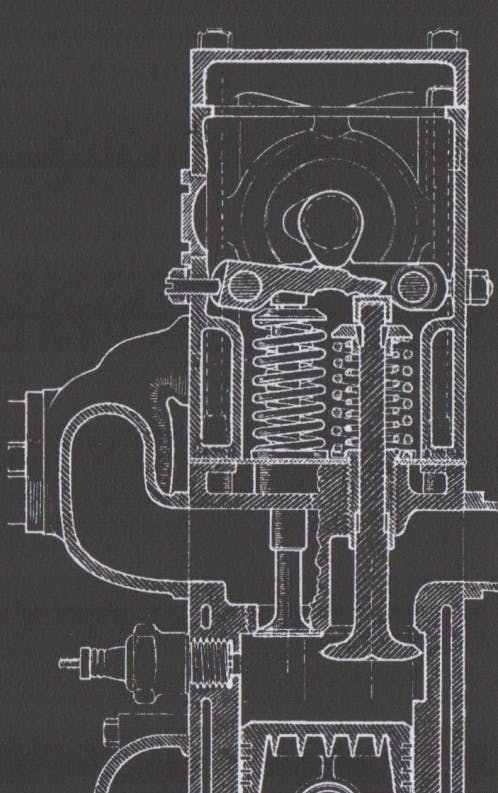

This was a 1600-pound device. The engine, a 2.0-liter, single-cam straight-eight, was designed and built in-house. Its simple and blocky exterior was engine-turned, machined with interlocking circles, like the movement of a fine watch. The bits inside gave around 100 hp at 5000 rpm, though they could see 6000 without damage. Top speed was around 130 mph. To that Ettore gave four cable-operated drum brakes.

At the bottom of that engine was a crankshaft running in roller bearings. If you don’t know what that means, don’t worry—we’ll get there in a moment. For now, know that a Bugatti roller crank is gorgeous but purposeful, delicate but relatively durable, simple in some ways and complex in others. It is also more demanding of attention than you might guess, and in ways you might not expect.

Those words, by the way, could describe almost anything Bugatti.

A few weeks ago, I went to Laguna Seca for a vintage race. In the paddock, I met California’s David Wallace, one of the world’s few experts on the rebuilding of prewar Bugattis. Wallace was at Laguna as support for American vintage racer Charles McCabe (“I’m his machinist,” he told me), but he spent decades working for renowned Bay Area prewar specialist Phil Reilly & Company.

Why did I ask Wallace about spendy-pretty roller cranks built a hundred years ago by France’s greatest speed prince? No one was there to stop me. He was friendly. I am never without questions. Pick a reason. Regardless, we were standing not far from two Bugatti Type 51s (basically a twin-cam Type 35) and my head went all artsy and loud.

“Nothing is too beautiful,” Bugatti is supposed to have said. “Nothing is too expensive.”

“The analogy,” Wallace once told the San Francisco Chronicle, “is great art. If you really like Picasso and you have the money, you buy a Picasso.”

Except: Imagine if that painting went 130 mph. If you could climb into that Picasso and fire the whole thing into a corner just as fast as it would go, slipping and sliding while high on French-Italian romance blat with a bunch of eight-cylinder wind up your honker?

You would do that, with your million-dollar piece of art, right?

***

David Wallace: So … the story is, a Bugatti crankshaft will go 5000 miles.

Sam Smith: [Laughs] Before what? The owner runs out of money?

DW: That’s the lifespan of a roller crank! Or what the factory used to say, at least. Five thousand, or whatever the kilometer equivalent is. And so, part of the way you take care of them is multiple oil changes. You have to change the oil all the time.

SS: I’m guessing there’s more to it.

DW: You can run a modern filter, inside the old canister, that filters better than what they had then. But … when you warm the car up, the oil is cold. What happens with roller cranks is, the rollers [in the bearings] skid on the cold oil, they don’t roll. And if they get a flat spot on them [from that skidding], they’ll always end up on that flat.

SS: And keep wearing on that flat, making the wear worse.

DW: So the trick is, when you warm them up, it’s not a bunch of revving. You start it up, it’s a constant rpm—wahhhhhhh, you know. And then there’s a slow throb of the throttle—waAAHHHwah, waAAHHHwah. No blipping.

SS: Patience.

DW: If you’re patient with the warmup procedure, that’s half of the wear right there. That’s when it starts.

***

A Brief Aside on the Nature of Crankshafts and Bearings

Don’t care about engines? Don’t leave. This is fun. Plus, he said, without an ounce of sarcasm, we get to talk about the basics of reciprocation!

Picture the engine of a modern car. It is essentially a big metal box. Pistons live in that box—four for a four-cylinder, eight for an eight, and so on. At the bottom of each piston is a rod. That rod is attached to the piston bottom, hung from a bearing surface in a manner that allows it to pendulum back and forth in a single axis.

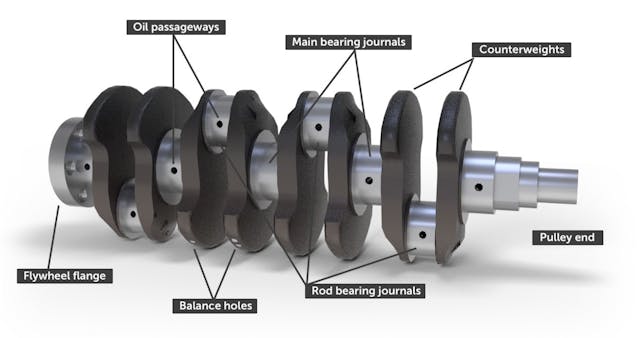

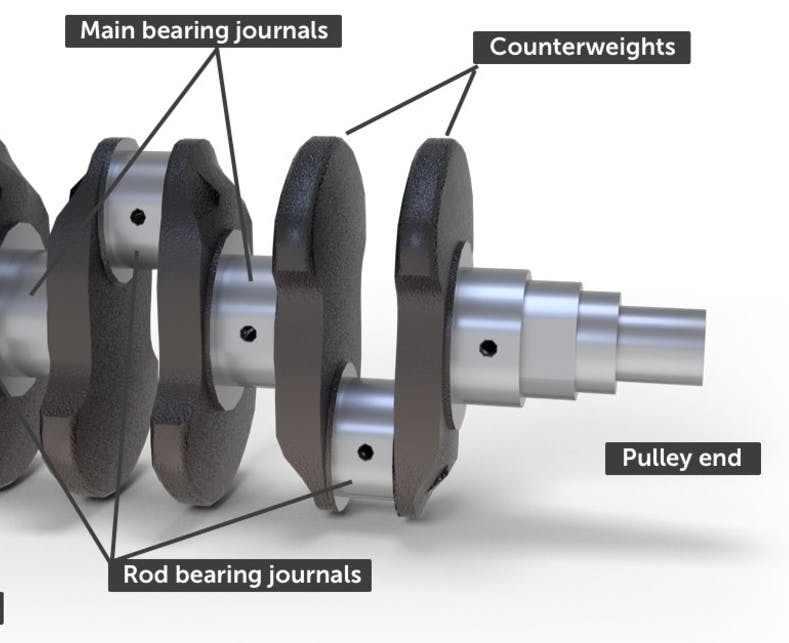

The bottom of each rod sits lower in the engine’s “box.” Each bottom is connected, by a bearing, to a single large shaft.

Viewed in profile, this shaft resembles a series of waves. It has peaks and troughs. The rods connect at those points.

Do you have a helpful gif, you ask? Why, yes we do!

As the shaft turns, the peaks and troughs trace an orbit. The rods and pistons move with them, pushed up and pulled down. Above each piston, at the right time, fuel and air are drawn in and burned. That burning produces gases that expand, and that expansion creates pressure. That pressure drives the pistons down, turning the shaft.

And there you have the basic geometry of a reciprocating internal-combustion engine.

That shaft is called a crankshaft. The timing of its push and pull is critical. Arranged one way, it can allow an engine to produce even, usable torque. Change the geometry even slightly, that same engine will refuse to start. The difference can be invisible to the human eye.

Simple, right?

Modern crankshafts are forged or cast from hard metal, their geometry fixed. They are engineered to last hundreds of thousands of miles. Modern cranks also spin in what is known as a “plain” bearing. This is essentially a tubelike metal surface, often plated or coated, that is fed a thin film of high-pressure oil. The bearing takes the load of the crank’s forces, but the crank actually rides and spins on the oil itself.

In the 1920s, high-performance engine oil was relatively young. Same for bearings. Crankshaft bearings were often poured in place using melted metal. (The modern version of that idea is a simple, replaceable shell bearing insert, which is designed to simply pop in and out.)

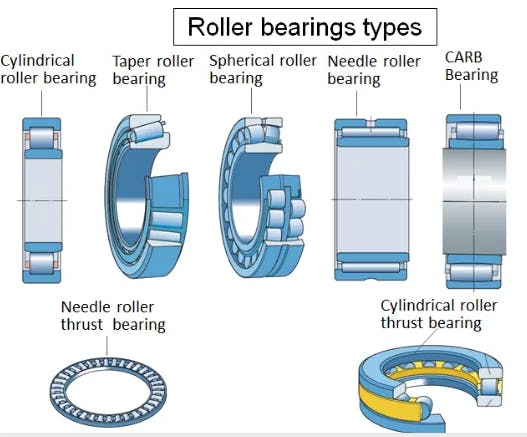

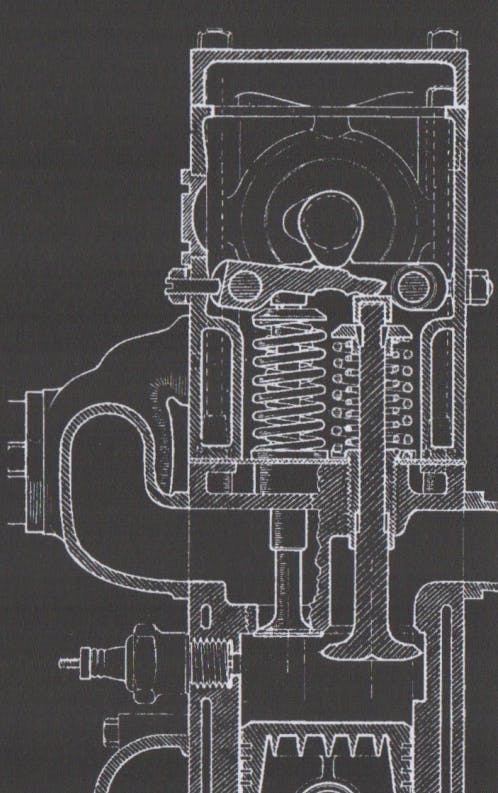

Whether poured in place or a modern shell, plain bearing “tubes” are commonly assembled from two halves. Each half resembles a metal potato chip. Roller bearings look like tiny barrels—the rollers—running in a circular track.

Rollers need lubrication, but nothing like that of a plain bearing—because rollers carry load differently, the oil must do a different kind of work. This generally requires significantly less oil pressure. A properly engineered roller application can thus get by with “splash” feed—oil simply tossed in the bearing’s direction by other moving engine parts.

Some vintage engines have components designed solely to throw oil around. Those parts are called “slingers.” Fun fact: In the years when oil seals were made of things like rope and prayer, slingers were also used to throw oil away from seals. The practice was equal parts physics and hope.

If all this sounds crazy, it’s not. It’s just old.

So: Bugatti crankshafts, and connecting rods, ran in rollers. This practice was relatively common. Especially with racing engines, and especially between the wars, when many mechanical failures were caused by oil or bearing issues. Plain bearings given suboptimal oil pressure would often seize. Large chunks of metal would then continue trying to rotate and break apart, scattering inside or through the engine’s walls, freed from the tyranny of useful geometric path.

Modern engine or vintage, the result is usually Bad. In the days before plain bearings really grew up, Bugatti decided that a roller crank was simply the most reliable choice.

Recall how plain bearings often come in halves. This is to facilitate installation around items like crankshafts. Roller bearings suitable for crank and rod use are manufactured as complete units, unable to be split. Assembling those units onto or into anything almost always means pressing them into place.

The image below shows a generic modern crank. Look at the bearing journals—see how they’re “trapped” between those big lumps of metal? (The lumps are counterweights; their mass lets the shaft rotate in balance.)

Picture how you slide a ring onto a finger. Putting a roller bearing on a crankshaft, anywhere but at the shaft’s ends, means taking the shaft apart. The complication lies in designing the part to allow that.

Roller cranks are not unique to early racing cars; they have appeared in, among other places, two-strokes, Hondas, and certain air-cooled Porsches. Most of those cranks were designed to be pressed together around their bearings, a practice pioneered by a Stuttgarter named Hirth.

In the case of Bugatti racing straight-eights, however—and Mr. Wallace will explain this in a moment—certain elements of crank geometry are essentially adjustable. Assembly takes hours and fat skill.

The result looks like this:

An elegant and reliable ingredient in a larger but equally elegant weapon. One small part of more than a thousand wins in just two years. And part of how you make a family name so powerful that it is twice later resurrected for new supercars and, in the second rebirth, applied to what is likely the last true moonshot of the internal-combustion era.

Plus, it just looks cool.

Back to Mr. Wallace.

***

SS: This engine design is basically 100 years old. Is there anything about it, or its assembly, that modern technology has helped?

DW: As far as performance, there’s not much more power [than in period]. We’re running more compression ratio than they used to, because the fuel’s better …

SS: How much then, versus now?

DW: They were probably around 7:1, with supercharging. It’s up to like 8:1 now. Of course, the more power you get out of an engine, the harder it’s working. But I don’t think [that added work is] a big factor in wear.

SS: And the cranks are still basically assembled as they were.

DW: Well, the crankshaft itself is a very complex assembly. It has taper pins, and the taper pins are what time the journals to each other . . . you have to [set that timing when you assemble the crank], grinding the taper to get the angle right.

SS: The first time I saw a drawing of that part, my head went vapor lock. Those pins literally set how and when the pistons move.

DW: And we’re talking thousandths. It has to run true within a thousandth [of an inch] or so. So it’s a very fussy job. It’s one of those things where you tighten it, and it runs true, and then you cinch the nut down and it’s off again. It’s so hard to get it tight and true, you know.

***

A Few Brief Notes on the Man Himself

A series of illustrative facts and potentially tall tales regarding one E.I.A. Bugatti, 1881 – 1947.

For all the man’s pioneering work, he was often wary of new technology. As the rest of the world adopted hydraulically operated brakes, Bugatti famously stuck with his trusted cable-and-rod setup. (I like to picture the man harrumphing: “Pipes full of liquid! To stop a car! Nonsense!”) He was, similarly, a late adopter to supercharging. In a time when it was not uncommon for half a racing grid to DNF from mechanical failure, Bugatti simply prioritized ideas that finished.

No king bought a Royale new, though one tried. King Zog I of Albania inquired about a purchase. Bugatti refused to sell him a car. The man, he said, had table manners “beyond belief.”

There are many stories like that. Most seem exaggerated caricature. Complicating matters, printed Bugatti histories often disagree on the veracity of familiar tales. Regardless, many of those tales fit an image. For example: When a customer complained about his car’s braking performance, Bugatti is said to have answered, “I build my cars to go, not to stop.”

One customer supposedly returned several times, in short order, for repair. Are you the man who has brought his car in so many times, Ettore asked? Yes, the customer said, sheepish. Bugatti’s response, according to lore: “Do not let it happen again.”

Bugatti’s fabricators, line employees, and race drivers occasionally went weeks or months without pay. Like many high-end carmakers, the marque had cycles of boom and bust. Employees stuck around out of loyalty, viewing their jobs as privilege.

Bugatti factory driver and 1930 Monaco Grand Prix winner René Dreyfus once told a story about how he dealt with this issue when needing funds. You did not ask about missing pay, Dreyfus said; that might get you dismissed. “If one were not paid,” he said, “it meant only one thing: there wasn’t any money.”

So Dreyfus would go see M’sieur Pracht, Bugatti’s treasurer, and have what he called “a bright little conversation.” Pracht would then allow him to take a new chassis or two to Paris, to sell to a local dealer and collect the purchase price. Money that Pracht had told Dreyfus to keep, quietly, as back pay.

In short, Bugatti made good on his debts. But those debts were not something one would be so crass as to discuss.

The Molsheim château grounds included: stables; a riding hall; kennels with more than 30 fox terriers; dovecots, a museum of sculpture created by Ettore’s brother, Rembrandt; a museum of historic horse-drawn carriages; a distillery; and a power plant. Some clients were allowed to stay in Bugatti’s on-site hotel without pay; others were required to settle their bills. Some of those bills were higher than others.

“In Molsheim,” Dreyfus said, “one did not, if one were a driver, need money in order to live well.”

Factory hand tools were stamped or cast with his monogram: EB, with the E backward. Those tools are said to have rarely left the property. It is fun to imagine why. Or rather, to imagine what the man might do, if one’s workstation were missing, say, a wrench.

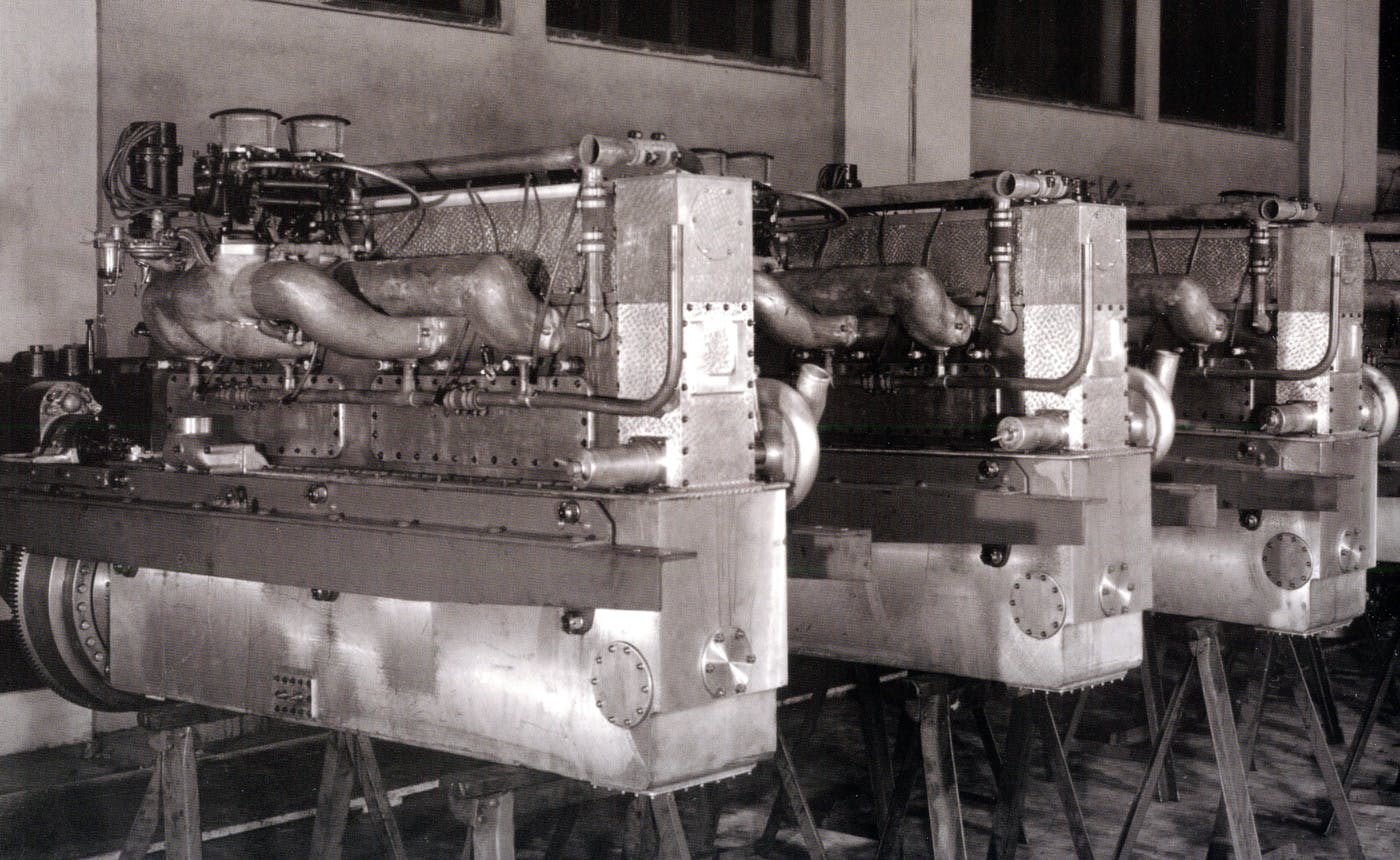

When the Royale did not sell as planned, Bugatti designed and built a rail car to take its engine. A self-powered, high-speed train. These cars, known as Wagons Rapide, eventually entered production. They were used on the government-owned French État rail system. Many models were driven by two Royale engines apiece; some used four. Development took less than a year.

The WR, an automotrice, was in service from 1935 to 1958. In early testing, one example was logged at more than 100 mph; some sources say the cars were still pulling at 120. The president of France traveled in one. The Royale itself did not make money, but the WR made the project—and more important, its expensive engine tooling—profitable.

When the first [WR] was finished, it was evident that Le Patron had, as it were, made an oversight. The railway station was a mile distant, and there was no track. Indeed, M. Bugatti had not even had the automotrice built on track. It had been built on the floor. And it would by no means go through the gate in the wall that solidly surrounded the factory.

Bugatti was not disturbed. He spoke to one of his supervisors. “Knock down the wall, if you please,” he said, “and ask 800 or 900 of the men if they would be good enough to push the car down to the station for me tomorrow night.”

—Ken Purdy, Ken Purdy’s Book of Automobiles

Oh, and: The rail cars used cable brakes.

***

SS: These are old machines made from old castings, but they’re also racing engines. Which means they are built to tight tolerance and regularly see high stress.

Race cars are good at wearing things out. And yet a 1920s Bugatti roller crank isn’t straightforward or easy to make.

DW: There are definitely craftsmen. It used to be that Brenetton, in England, would just sell you a new crankshaft. I think they still will. They definitely had all the tooling to make them. So it can be done. The metallurgy’s better now, more controlled. They were pretty good at it, though.

When things get old, it’s not so much time, it’s cycles. How many cycles? This is a vibrating part. It’s like, How many times can it do that flex before it breaks?

With crankshafts, it’s usually not cycles. It’s a matter of the rollers wearing out. The old fix was, you would grind the journal and put a bigger roller in. Well, you can only do that so many times. Some shops, like Ivan Dutton in England, have developed a needle roller for their [connecting] rods. Using tiny rollers, and that does work.

SS: It’s just a caged needle bearing?

DW: Yeah. The rollers are much smaller. The stock roller on a Bugatti, I think, is 11-millimeter diameter. And the needles are, you know, needles, four millimeter in diameter. So they’re not as sensitive to acceleration, deceleration. They’re so light, they don’t skid.

And then the Pur Sang Bugattis . . .

SS: The “toolroom copy” new ones? Those engines were reengineered for plain bearings, right?

DW: Yeah. So they avoided the whole problem.

SS: Has anything changed with time, as far as making an engine like this live at high rpm? Upgrades, things you can or can’t get, knowledge or skills that have gone away?

DW: Well, definitely, the fuel-air-mixture technology—it’s much better now. They were looking at the color of spark plugs or listening to the engine [to get fuel mix right], you know. With [modern] air-fuel sensors, you can just dial the thing right in.

What’s funny about that, though, is that there aren’t enough adjustments to really get it even across the whole band. Modern cars have infinite adjustment. To get one of these old carburetors—really only a main jet, and an idle jet, and an air-mixture screw—to come up with an across-the-band answer, it’s pretty hard to do. So we try to look for the power band, and the rest of it, you just run it rich [for safety].

That’s a technology that’s come a long way. And the fuel is definitely better than it was. We don’t run electronic ignitions or anything—people have tried it, but the magnetos are just fine.

Note: Magnetos are neat and reliable pieces that essentially package an entire ignition system, minus spark plugs, in one small mechanical component. They’re mostly found in vintage cars, tractors, and light aircraft. Here’s a primer. —SS

***

A Random Type 35 Fact Loved By Your Narrator

The 35’s 28-inch, eight-spoke aluminum wheels arrived at a time when the entire world believed wire wheels were as good as it got. Each wheel was cast with an integral brake drum, the drum lining pressed in after. The entire assembly weighed four pounds less than the average racing wire wheel.

The same individual who brained up this technology also patented or invented countless other items: bicycle frames. Fishing rods. Doors. Lighting fixtures, surgical instruments, window blinds, even security locks.

“The design of these engines is entirely characteristic of Ettore Bugatti, being unconventional in nearly every aspect, demanding the utmost in skilled workmanship and fitting, and yet, at the same time, reflecting a severe, almost brutally practical outlook.”

—Racing historian Laurence Pomeroy

(Hat tip on the quote to the legendary Dennis Simanaitis!)

***

SS: Prewar grand prix cars are all so different from each other, so varied in design and durability. Is there even such a thing as an average time between overhauls? A TBO?

DW: Oh, I go by events. And it’s hard to estimate. Probably . . . ten to 20 events?

At first you think, Okay, it should go at least, like, four race weekends before there’s gonna be a problem. But you do routine checks. Leakdown, valve adjustment, compression tests . . . if it keeps passing those tests and it’s not burning oil, I have no problem running it until it shows a problem.

(The interview went off-topic here for a moment while I asked about another prewar nerdism, the preselector gearbox. The following line regards preselectors but made me smile, so I’m leaving it —SS )

DW: It’s not like, is it timed out, like a modern car? It’s more about disassembly and inspection. Measurement and crack tests. If it passes all those things, back in it goes.

SS: There’s something about the Bugatti story that means so many of the cars find owners who understand how and why they were built. Nobody buys one out of fashion, like with a new Ferrari.

You’ve been around old Bugs for decades—has anything changed in how the owners see them?

DW: I can’t say if it’s different. I do worry that some of them are getting too precious to come to the race track, or to go on events.

Some of the reproduction cars are showing up at events because people don’t want to race their authentic car. Because, you know, it’s expensive. But there’s still a pretty good core of people that want to race and drive the real car. The American Bugatti Club has a thousand members. They can pull together 50 cars for an event—that’s a lot.

We just did the Bugatti Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, and we only had 16 cars in the race. I’ve run the Bugatti race at Goodwood where we had twice that, you know? But I think they’re always going to be cherished items, I think they appeal to the gearhead in all of us.

SS: [Says polite thank-you words, then goes and sits on a Northern California hill to watch a great many old machines make a great many noises at high speed, happier than a pig in . . . well, you know.]

***

Postscript: No Bugatti discussion would be complete without mentioning how your narrator is a nerd for René Dreyfus, the grand-prix driver mentioned above. Dreyfus was one of the best at the top of the sport, winning often. Interviews paint him as a funny, kind, and deeply mannered gentleman.

In later years, Dreyfus moved to America and opened a French restaurant in New York with his brother. He wrote a book on that life with a former editor of Automobile Quarterly. The restaurant was called Le Chanteclair. Around 30 years ago, Road & Track sold reproductions of the restaurant’s ashtrays.

Those repops occasionally pop up on eBay for twenty or thirty bucks. One lives on my desk. I can’t afford a Bugatti. Even the Dreyfus book is now expensive. But the little bits and the stories—they belong to everyone.

***

Want more stories from our Great Reads project? Click here.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

What has always amazed me about Bugatti was how his drive for perfection in style and engineering is what made him so special and often cause him may issues.

Bugatti lasted as long as the old man did and after he was gone that was it. Yes we have a car today that is a bit over over the top engineering like the original but it is too well built to German standards and just is not the same.

These are cars that did influence much in the industry and left a mark even though they are cars today many have never seen in person.

Even the plane EB designed finally was reproduced and flown. It did fly but it had its difficulties too and we lost the builder.

I always take notice a lost car is found. It feels like most of these cars are still out there in hiding and with each one found it makes for a thrill to see it in color in present day vs some black and white photo.

I got to know Rene Dreyfus back in the mid-1960s, when the magazine I worked for was located near Le Chanteclair. I ate there often and chatted with him every time I visited. I was so honored that he soon came to recognize me and welcomed me into his large circle of regulars. What a fabulous man.

Loved your article, by the way. A delight to read, unlike so much–nearly all–automotive commentary these days.

I appreciate that—it means a lot, coming from you. And I cannot imagine knowing the man. That is . . . remarkable.

For the record, I very much enjoyed Gold-Plated Porsche, but also your work in Flying and C/D. I also find myself reading a small set of your words every year or so, in a foreword, every time I settle into a chair on a dark night in winter and burn through Bax Seat again. (The book of columns, not the column itself.)

“Wouldn’t recognize class east of Natchez if it were an international-orange rudder lock” always made me chuckle.

Thanks, Stephan. And thank you for reading!

Dreyfus to Wilkinson to Smith–something like the Papal Succession. I now benefit from what the masters have passed down.

In spite of having gotten a B in ninth grade “Shop” class, I struggled through much of the engineering detail. Looking back, I wish I could have had an article like this when I was 30 and still had the time to move past the simple pleasures of speed and gear shifting and on to the deeper joys of The Oiling of the Bearings and the The Turning of the Screws. Thank you, Grand Sam. (And a belated thank you to Mr. Wilkinson for the “rudder lock” trope. Wow!)

Hise, you are, as always, too kind. Thank you.

(Related: I suspect you’d like the Gordon Baxter book. “Bax Seat: Log of a Pasture Pilot.” Out of print but still available cheap. Try to get the first print with the illo of Bax and the Stearman on the cover, just because it’s pretty. The man at his best.)

Hello, Stephan Wilkinson. Hope all is well with you. I have an “Obsidian-Plated Porsche.” I tell folks I will sell it only when I become so infirm that ingress and egress require assistance.

Great work, Sam; a very good and enlightening read.

Great read Sam! I, like you am a total geek for ’30s era Grand Prix racing and the details. Regarding Rene Dreyfuss, I’m sure you’ve seen or read Neil Bascomb’s recent book entitled “Faster” which offers a wonderful look at his life and his connection with Lucy Schell and the 1938 Pau Grand Prix.

Interestingly, he drove for almost every top racing manufacturer of his time including Bugatti, Delahaye, Alfa-Romeo, Maserati and ultimately Ferrari in his last shot at LeMans after the war, with the exception of course of the German manufacturers for obvious reasons.

A true gentleman who had some interesting thoughts on and experiences while driving for Bugatti. If I’m not mistaken, the T-35 continues to hold the mark for the most victories, could be wrong.

Fascinating article, appreciated.

I love the mechanic with the filthy overalls over a shirt-and-tie at Monaco!

Your picture of the cable brakes on the front wheel also shows another Bugatti piece of art. Note that the spring passes through the axle. Not under, not over, but through.

A friend had a Tyoe 40 Bugatti, the entry level Bugatti! I helped him a lot with the car. It was both fascinating and infuriating, but never dull.

i suspect that Sam knew that when he wrote the caption, “clever forged front axle.”

Very cool story. I loved the technical bits on the engineering done.

More such articles please.

Sam,

I assume you’ve met George Davidson in Louisville (your hometown)? He has two T35’s; one in Louisville that he drives to Cars and Coffee and another in “jolly old England” that he tours the Continent with. He’s one of the most low key guys you could hope to meet, with amazing knowledge of the mark! Great guy!!

Excellent article…you are a gift to we readers. Thank you!

Oh, man! If George is who I’m thinking of, I remember seeing his T35 at car shows in the 1990s? Or at least, I remember seeing a guy running down River Road in a French Blue 35 and thinking, “Oh?”

Thank you for the kind words, and for reading!

Agree on all of the comments above. I LOVE this vintage racing stuff!

Certainly, at least in my estimation, the finest article ever printed in the bulletin. Many thanks to the Hagerty media staff, and to Hagerty Insurance, the best insurance company out there.

There were those experienced with both in the day and since who preferred Alfa Romeos, others decried Bugattis’ “porous castings” and other maladies. But the cars were stoic artistry.

Well done, expansive, balanced article, Sam. Thank you and Hagerty.

Thank you for the excellent article. I consider Hagerty magazine to be what R&T once was.

This story brought back memories of being at Laguna Seca in 1986 during the historic races with a now deceased friend. We were walking around the pits when four or five Type 35s fired up and left the pits. It was magic! My friend Doug recorded this for posterity. I also recall walking past three 250 LMs side by side in the pits. One was just firing up when I noticed antifreeze running out from under it and I motioned for the owner to kill the engine. Doug drove a 1985 Mustang GT and as we left that day we followed a 1950s Ferrari (340 America I believe) puffing smoke with each upshift. What a day!

I’m fully familiar with ICE internals but “the tyranny of useful geometric path” gave me a new perspective on failures!

And magnetos are still on every small engine.

I think chance encounters or appearances at low-key events will become vanishingly rare, unfortunately. There used to be a couple of Bugattis (I think at T35 and a T37) at the Mount Equinox Hill Climb in Arlington, VT, a delightfully egalitarian event where everyone was happy to talk to you. No longer — I heard that the prices for them in Europe got so out of hand that nobody could justify having a tatty functional example.