Media | Articles

Smithology: Systems in flux, afterthought hair, the Blackwing torque faucet

An editorial note to the reader: This is not exactly a CT5-V Blackwing test, but it is also not not exactly a Blackwing test — jb

Hard truths abound these days. Our political discourse is a wreck. Our wealthiest and most powerful people devolve to online pissing matches over just how, exactly, they should let other powerful people take expensive vanity vacations in space. One of the most famous individuals on earth builds a new car whose most well-known beta feature regularly kills people, and if you are so stupid as to point out this fact in a public forum, his fanboys will hatepost you into the stone age.

In the middle of all this, we have the Cadillac CT5-V Blackwing.

“I don’t know if I like it,” the delivery driver announced, after pulling it off the truck.

“Glenn,” I said—for his name was Glenn—“no sir.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“Yeah?”

“I want five of them.”

Glenn looked skeptical. A bright-blue, executive-spec Cadillac thunderbus is, after all, a divisive thing. Even if the car in question has a clutch pedal, which this one did.

Glenn arrived at my shop in a tractor-trailer hauling that blessed-event Cadillac, but also a brand-new Honda kei truck, on its way from a Detroit supplier. We bonded over the kei truck. He found it funny and lightly charming. (Smith’s fatal flaw #9003: I almost immediately trust anyone who expresses even an ounce of faith in a tiny Honda.)

“Why?” he asked, with the Cadillac.

“Kinda hard to explain, Glenn.”

“I guess,” Glenn said, in a manner that suggested he thought I was full of it.

“Shame is, they won’t sell. A handful, maybe.”

“You think?”

I shook my head. “Betcha five bucks. They don’t sell many BMW M5s, right? Or Mercedes E53s?”

“Kind of a hot rod.”

“Yeah. This is more special and more fun but less of a status symbol. It used to be called CTS-V. Almost nobody bought that car. How many people you know who want a 668-hp rear-drive track Caddy, and more important, can actually spend nearly a hundred grand on one?”

Glenn nodded.

I sighed. “Me either.”

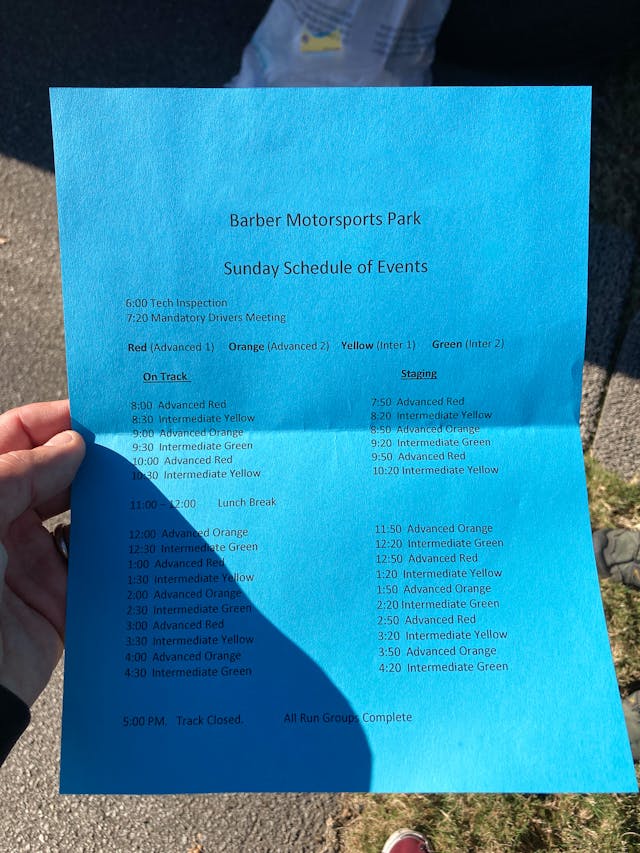

BARBER MOTORSPORTS PARK, LEEDS, ALABAMA

Twenty-four hours later, I was rolling into the brake at Barber. Turn one and a green flag at a track day in an unstoppable Cadillac! Near-zero lock on the differential at turn-in, said the dash display! Tire pressures nominal, it said! The stereo said no actual words but conversed with my phone through wireless CarPlay and various unknowable ones and zeroes, playing a Glenn Gould version of a Beethoven piano concerto as interpreted through a French high-res streaming service. That whole sound-system business took place at maximum volume, as to be heard over lowered windows and the noise of a public track day, while the LT4 up front grumbled and baroomed its way into a downhill left with a fat apex curb in the middle.

The 2.3 miles of asphalt at Alabama’s Barber Motorsports Park is variously off-camber, climbing, falling, or fast; some of it is all that at once. The curbs are tall and generally to be avoided, unless you happen to be driving a device that adores curbs, in which case you climb them like a juiced monkey and slap out throttle like the world is ending.

Beethoven seemed proper. It was either that or the Clash, I thought, as I idled toward the hot pits and tightened my helmet strap. Then I tried the Clash, and it didn’t really fit. Too on-the-nose for a car the color of a rutting Smurf.

How that car turns! It wallops into a corner an instant after (or as, or before) the electronic diff and the electronically controlled magnetorheological shocks confer with multiple chassis load and position sensors. A stack of silicon chews on throttle position/steering position/lateral load/rpm/gear/suspension compression and gives perhaps a think on your tarot readings and the winds of Jupiter. That diff is always whip-cracking open or bleeding into some helpful percentage of lock—the digital dash tells you how much. Only a dork would look at this information while lapping a road course, so I looked at it a lot.

The Blackwing’s chassis firmament changes constantly in small doses, depending on chosen mode and your driving style. Each change takes unknowable milliseconds. A Cadillac engineer who worked on the project once told me to think of all this as a set of software if-thens built to help the car do what the driver seems to want. “Even if you’re not quite sure what that is,” he said. For my part, I smiled and tried to not think sheepish thoughts about the times I have had to work to problem-solve while helping dial the suspension on some club-level race car, with its puny five or eight variables per corner and precisely no software or five-dimensional sorcery-suspension-control-maps whatsoever.

That silicon chassis-sussing process is not unique to this particular Cadillac, or even this particular car company; General Motors simply does a better job of it than most. I would be lying if I said I could fully explain it—there is so much going on, the car’s systems constantly in flux—but I do notice bits of the result. An outside front shock will seem softer than a moment back, or marginally stiffer. Or the car will simply snap into a high-speed and off-throttle pivot in a predictable and friendly fashion that also makes absolutely no sense next to its behavior, ten seconds ago, in a slower corner. Nonlinearity, for the better.

Mostly, you do not think about this stuff. A very large Cadillac simply barrels through a lap like a bank vault would barrel toward the ground when dropped from an airplane. And a man with an alliterative name attacks a piano on AKG-branded speakers while you sit in the optional carbon-backed sport seats that also happen to fit the wide of hip.

“To play a wrong note is insignificant,” Beethoven once said. “To play without passion is inexcusable.”

You ever wonder what kind of car ol’ Ludwig would have built, if he were the car-building type?

Professional writers must often pitch their stories to superiors. We will take a brand-new CT5-V Blackwing to Barber for a public track day, I told the editor of this august publication, and we will have an entire weekend of a great car we would normally only test in small doses.

“Why would you do this?” he asked.

“Because this is the last of a breed,” I said. “The last gas-powered performance track Cadillac, and the last with a clutch pedal. GM says everything after this will be electrically juiced. A big sedan with big pistons, built for a customer and world either dying or dead, depending who you ask.”

“Sure,” this editor allowed.

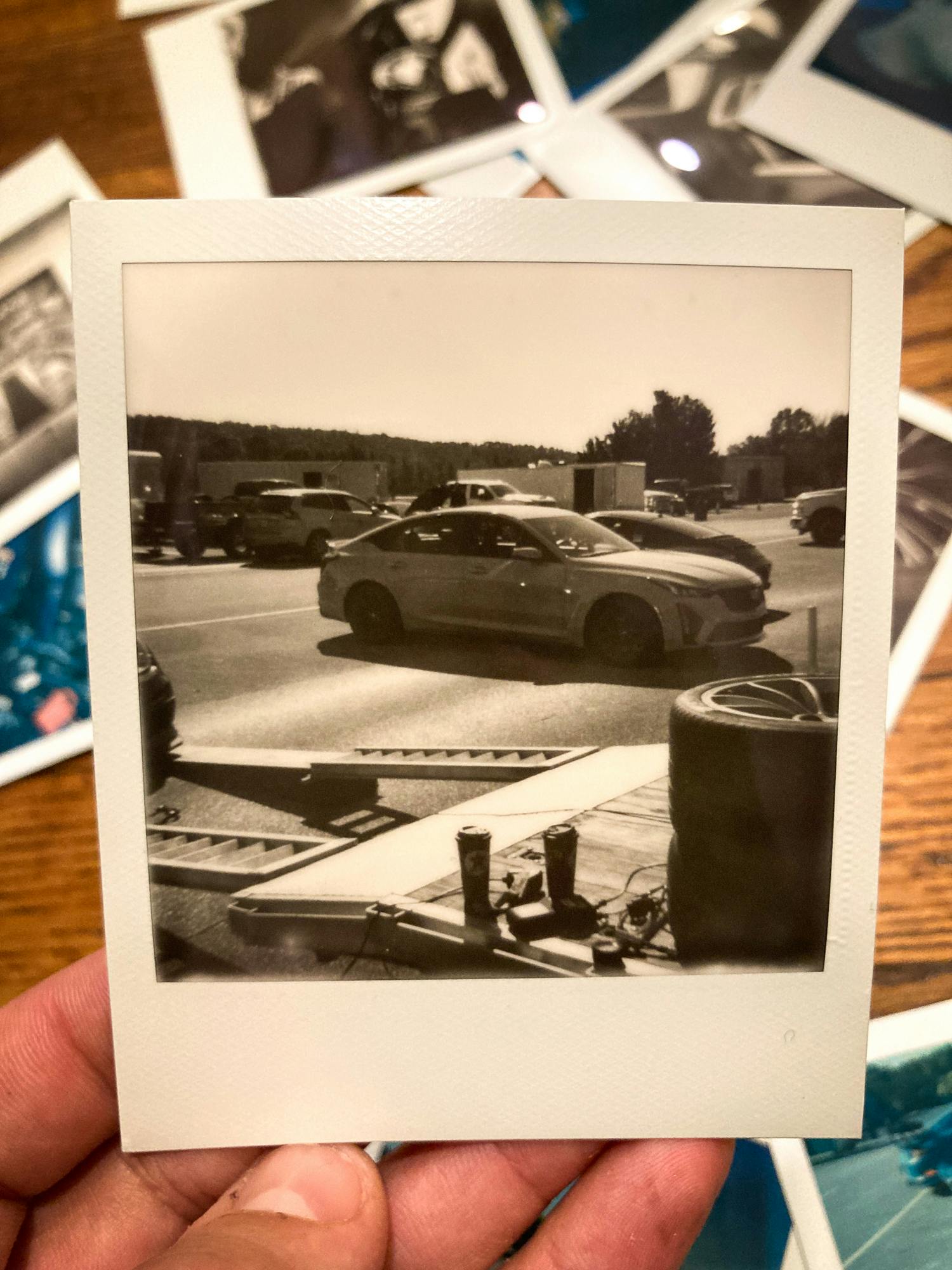

“No more buffalo, like McMurtry said. Also, I want to shoot it with a Polaroid instant camera.”

Silence.

Polaroid stopped making instant cameras years ago. The company went bankrupt in 2001 and again in 2008. During the second bankruptcy, a group from the Netherlands started something called The Impossible Project, to reverse-engineer discontinued Polaroid instant film. Everyone who knew anything about chemistry said the task was—natch—impossible. Twelve years later, those Dutch bought the rights to the Polaroid name. Their website now sells restored vintage cameras and new instant-film packs.

Old instant camera made new. Digitally controlled last-of-a-breed Detroit muscle-sport sedan with a clutch pedal. Two items once seen as the future but now just a piece of the past, zombied back into relevance for the few who like that sort of thing.

“Sure,” the editor offered, when I finished saying all that. Knowing this particular man, there is a very good chance he simply wanted me to stop talking.

Everyone needs a boss who knows them well.

***

The truth is, the sport sedan is dying. The gasoline sport sedan, moreso. Most people don’t want cars like this, and certainly not in the numbers they once did.

Numbers justify everything in the car business, and no company is long for this world if it insists on building what doesn’t sell. The Blackwing is basically a face-lifted and updated version of the 2016–2019 Cadillac CTS-V. Cadillac built just over 5700 CTS-Vs from 2016 to 2019. That machine was arguably the most satisfying executive sport sedan in the world, but that fact is irrelevant; relatively speaking, no one wanted it. Given current automotive fashion, maybe the car would have done better if they had bolted a pickup bed on the back and called it a “safari prerunner.”

Some people in this business have chosen to write off the CT5-V ‘wing as a Camaro ZL1 four-door. The Caddy is essentially that. Its supercharged LT4 V-8 was borrowed, virtually unaltered, from the ZL1. So was the Blackwing’s standard six-speed Tremec. The ZL1 weighs about the same and uses the same digital philosophy to manage its suspension and driveline.

The difference is in how the Cadillac pivots and surprises. These days, who doesn’t expect a Camaro to turn okay? Most of the big sport sedans we have left are numb and jittery bullet trains. Or distant and joyless.

Call this car the golden version of an old ideal, as good as we could have expected back in the Sixties, when Detroit hit its stride with absurd road muscle. Like all those future-loving midcentury magazines where the answer was flying cars and wristwatch televisions, only we didn’t expect that our culture would one day find the wristwatch televisions far more interesting than cars or flying. And far more than mere watches or televisions.

Not too long ago, I wrote a track test that one reader called awfully “technical.” I had to laugh, because I am not an engineer. Couldn’t pass for one if I tried. I just like learning how things work.

There are times where the Blackwing could only work as it does if its differential had snapped out of lock in mind-reading fashion, freeing the car to turn. If a front shock had been gifted a great whack of rebound precisely as the outside tires ramped into load. Sometimes the car seems to see the slide you have put into the nose by accident; it will then offer up a series of responses that could be mistaken for a computer actively trying to coax the front back into grip. Steering feel and shock settings will be monkeyed with in such a way that you are nudged into driving in a manner that cures the problem. Then the front tires grip up and the car’s behavior changes again, and maybe the shocks seem to be carrying the car a little, but who cares, because it feels almost entirely natural.

The Germans and Japanese can’t pull this off with the same sense of fun. The Italians can’t make it feel like a real car.

It is remarkably stable on the brakes, especially while loaded and flying over curbs. Pop the inside front wheel over an eight-inch lump of concrete at the top of third gear under big throttle, the inside shocks blow off their bump stiffness in a heartbeat. Should the car have gone sideways at that point? Yes. Did it? No.

The LT4 is a 6.2-liter torque faucet. Seamless and instant and willing to snap the rear tires to smoke if you ask. That engine can suck down three-quarters of its 17-gallon fuel tank in just 30 minutes of lapping. The steering is nice but occasionally a bit artificial and odd, as if the assist motor on the column overdid feedback torque for an instant, then got stuck.

Too technical? Do we need instead some good old car-writer-impressed-with-himself hyperbole? How about this? Thunderbus megacar luxobabybarge can relentless around Barber at the pace of a well-driven Porsche Cayman GT4! Ollie curbs like Tony Hawk! M5-eater coming to eat your face! Asks Lamburgundys and Furlarlis to step outside!

Then you plop it into Tour mode and those digital talents aim for soft but controlled, like an S-class.

Highways are a delight.

Most portraits of Beethoven show the man in a broad scowl, face barely contained by the storming hair above. I like people who treat hair as afterthought. Several months back, during the press launch of the CT5-V Blackwing, I met some of the engineers who decided that a 4100-pound Cadillac needed to be around 20 percent better on a track than any reasonable person has a right to expect.

None of those individuals looked or acted like 18th-century German romantics, but they all had afterthought hair. One of those life details you maybe focus on less, when your care and passion is aimed elsewhere.

That track day at Barber was in fact two consecutive days. At the end of each afternoon, the track’s west-facing back straight would be bathed in this golden and blinding sunlight, to the point where I was occasionally lifting a hand to my eyes to block the glare while flat out in fourth. I ended up spending the last session of the second day—30 minutes, on a virtually empty track, because almost everyone had gone home—chasing a Cayman GT4. Trading places, lap after lap, as the sun set.

In a fossil-burning Cadillac with three pedals.

God, I love this thing.

***

Any time you write a sap-eyed paean to a new car, somebody in the comments shouts that the whole thing is a long-winded sellout. Unlike some other automotive publications, this media company has a stable business model and is not in a state of perpetual financial gutting. It is blessed with a solid financial case and thus does not concern itself with ad buys or review payoffs from carmakers. All General Motors gave us to facilitate this story was the loan of a test car and some tire tread.

Still, how many will notice? Some people believe that good fast cars no longer matter much. Those who spend enough time in the bowels of L.A. or New York or Chicago can get to thinking that the behavior of a machine in a corner is immaterial, solely there to keep grandpa from driving into the weeds. That a roadgoing automobile should be merely competent enough to keep you safe, emotion unnecessary.

And yet, we are out here! We happy few! We drive them and care about how they behave between the lines! The car is not a status symbol or piece of clothing! We are not all fortunate enough to live in the Malibu canyons, or in the pricey hills outside Portland or Austin. We like purposeful and talkative machines, and they can’t all be vintage or quasi-truck-pod-utility high-riders. We want to buy, or at least dream of, an alternative. We care, and we are more in number than just you and me.

You can’t get rich writing about cars, just like you can’t save a modern car company by building deeply emotional sport sedans for a dwindling audience. You can, however, get happy by doing either of these things, and you can meet others who love what you do. I know. They came up to me in that paddock at Barber and gushed on the car. One even ran up to me in the parking lot of an I-40 Taco Bell.

We aren’t huge in number. For that matter, many of us cannot afford an $84,000 Cadillac. But we are not, as Monty Python said, dead yet. And so help me, this car—this magnificent and wonderful achievement of a car—well, it’s for us.