Media | Articles

Car Design Fundamentals: The C-pillar

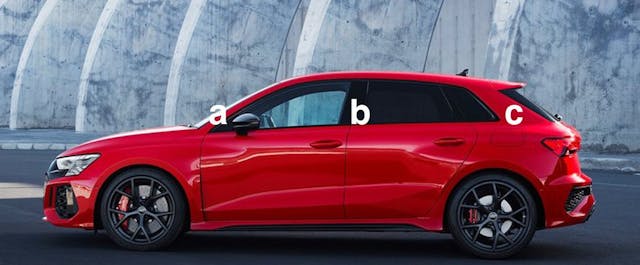

Welcome back to Car Design Fundamentals, your go-to reference series for auto studio lingo. We’ve already looked at how the A-pillar helps to describe the shape of a front of a car, and how its position affects dash to axle ratio. But the C-pillar is the key when it comes to describing the shape of a vehicle’s posterior. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the C-pillar is one of the most critical areas to get right.

The C-pillar is the structural upright visible from the side, and its also part of the frame around the rear window. That definition applies to many vehicles, including sedans, coupes, and hatchbacks. Wagons, CUVs, and SUVs have an extended daylight opening (commonly referred to as the side windows) over the rear wheels and consequently implement another set of pillars called, unsurprisingly, D-pillars.

Why should you care about the C-pillar? This body part is a complicated, structural stamping that determines the volume and position of the passenger cabin, the shape of the daylight opening (DLO), and it anchors the car over the rear wheel.

Much like how the A-pillar is the starting point of the passenger cabin (and the separation between hood and windshield), the angle and position of the C-pillar does the same at the rear. The base of the C-pillar should ideally sit over the rear wheels, and have a sympathetic visual relationship with the A and B-pillars and the DLO. Hatches usually have a steeper C-pillar rake than a sedan, but over the last twenty years or so the lines have become blurred.

To further muddy the issue, three-door SUVs may consider the rear pillar either C- or D-, depending on the manufacturer’s need for simplified lingo to match interchangeable parts between three- and five-door variants. Furthermore, most modern hatches have glazing or some kind of trim trickery happening behind the door glass. Whether this is considered a C- or a D-pillar depends on how much visual separation there is.

For example, the Tesla Model 3 looks like it should be a hatchback but it, bafflingly, has a trunk. The 2020 Skoda Superb has a three-box profile (just), but is actually a hatchback, demonstrating a most rational commitment to usability. Pulling the C-pillar forwards gives you a larger trunk opening on saloons (aka sedans), but will intrude on rear headroom unless you make it more upright. Pushing it backwards gives rear occupants more room, but go too far and the car looks tail heavy. On hatchbacks, the C-pillar tends to be thicker because it provides extra structural rigidity for its larger opening relative to a conventional trunk (and for modern-day roof crush tests).

Coupes traditionally have a much more steeply-raked C-pillar but the base will always be positioned over the rear wheel arch. It has implications for rear-seat passenger headroom, in the case of my Audi TT’s warning message regarding rear occupants’ heads when closing the hatch. (This must be the famed German sense of humor at work, because no one is sitting in the rear seats of a TT.)

The 1990 E36 BMW 3 Series was one of the first sedans to really start pushing the cabin volume backwards, resulting in a stubbier trunk with a smaller opening. BMW cleverly got around this by giving the trunk lid fancy (and no doubt expensive) cantilevered hinges, which swung the lid right up, and out of the way. Today’s Jaguar XE takes this idea to the extreme to the extent it has hardly any trunk at all; the appearance of a docked tail is the result.

What of that modern oxymoron, the “four-door coupe”? The idea is not that modern at all, because way back in 1962, Rover introduced a version of the P5 with narrower pillars and 2.5 inches chopped out of the roof line. It was called the Coupe but—nomenclature notwithstanding—it was just a slinkier three-box design.

The P5 Coupe shares that trait with the Mercedes CLS, as the big Merc is essentially an E-Class with the C-pillar nudged rearwards, and the roofline lowered.

The 2010 Saab 9-5 is an example of what happens when you push the C-pillar too far back and keep a large trunk volume; the large expanse of sheet metal makes it look visually very heavy at the back, not helped by its large rear overhang.

Another one done badly, albeit for a different reason: A recent fashion is to give the rear of the DLO a reverse rake. It’s tricky to get it right, and the Lexus CT200h is just a visual disaster. The backwards rake of the DLO impinges on the space for the rear side glass to drop into the door, and none of the shapes have any relationship with the others.

Thankfully we are beginning to see the end of this particular trend. The current fashion is towards pinched or “flying” C-pillars, which look much cleaner and more sophisticated. But of course, the effect is reduced when everyone is doing the same thing.

In conclusion, this and the previous article discussed the importance of the position of A/C-pillars, especially their relationship with the wheels. So that’s where we’ll be focusing next: wheelbase and overhangs.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence