Media | Articles

The EMC “Wolf” G-Wagen is a bucket of restomod fun

Though the G-Wagen was also first developed for the armed forces, in West Germany and elsewhere, the tech-laden G-Class of today is a gentrified caricature of these roots. It may still have the capability to ford rivers and climb hellish grades, but the truth is that it’s a Kardashian-esque luxury item made for Kardashian-esque people—a designer handbag you can drive. The classic G-Wagen experience is still out there for those brave enough to buy a survivor, but these are challenging vehicles to own and maintain. Fortunately there is another option available: Expedition Motor Company. EMC sources, strips down, restores, and modifies 1990–93 250 GDs—exclusively the so-called “Wolf” convertibles with their folding windshields. These are arguably the coolest G-Wagens ever made for civilians, and they benefit from more than a decade of refinement from the 1979 original—not to mention one of the most bulletproof diesel engines known to history. On the battlefield they are durable, reliable, and capable. On public roads they look like what Arnold Schwarzenegger would use to humiliate a Fiat Jolly.

EMC’s handiwork makes these rigs more creature-comfortable, not to mention weapons-grade Instagrammable. Where there was once thin upholstery and monochrome hard plastic there is now marine-grade vinyl, rich-looking two-tone stitched leather, and grained wood detailing, Vintage Air A/C, plus a modest digital screen for the backup camera sits in front of the dogleg five-speed manual transmission. No olive drab paint here either—how about pale blue, eye-searing orange, or moody gunmetal gray, or any other single-stage color for which you can find the code?

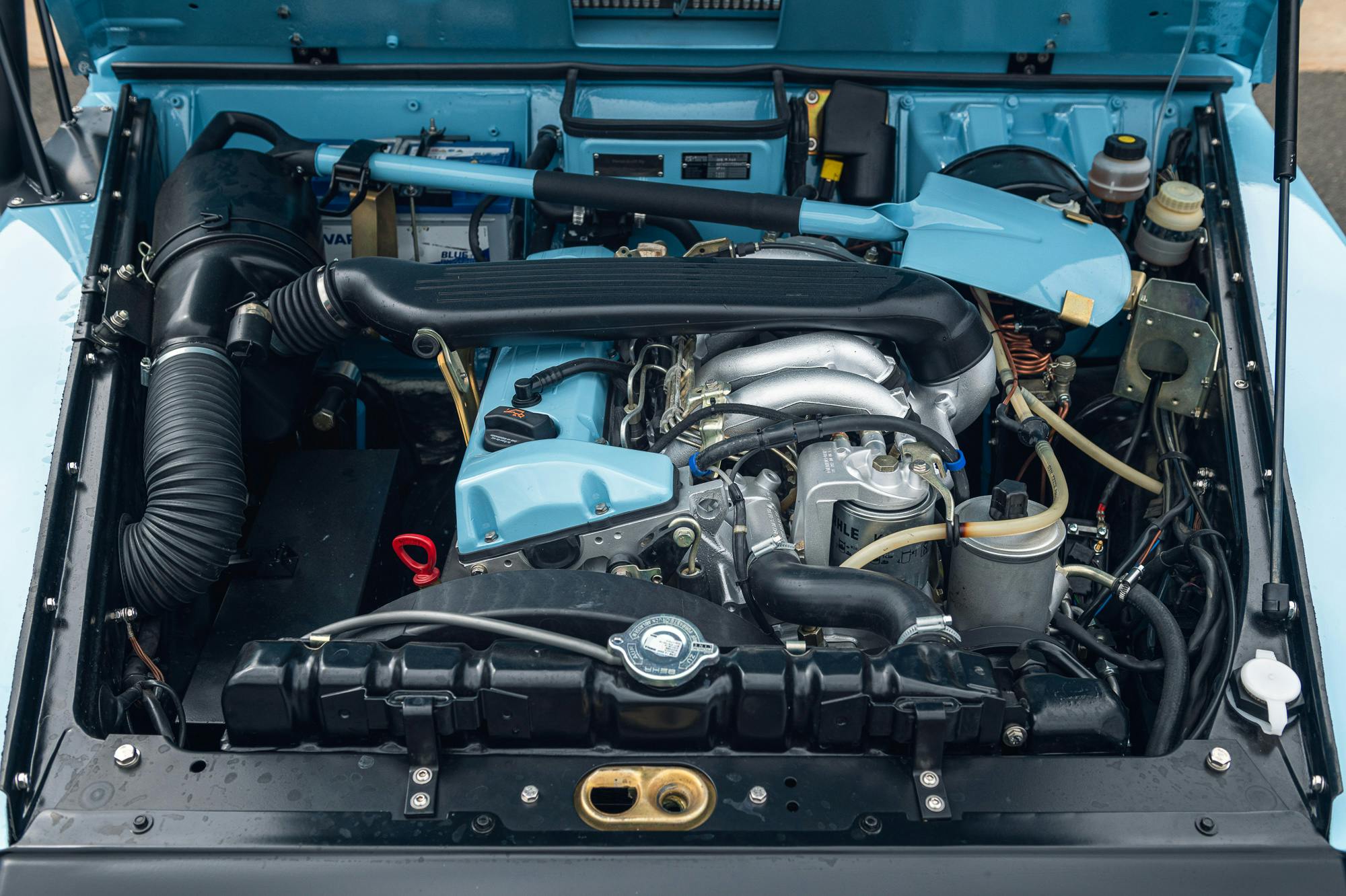

These $120,000 playthings might look like fashionable restomods now, but all of EMC’s builds start with ex-military vehicles—usually from German NATO forces and old enough to be eligible for U.S. import—that EMC buys after their lifespan is up. From there, about 95 percent of the restoration work is performed at the company’s 16-person facility in Bialystock, Poland. The process involves taking the Wolfs entirely apart, down to every last nut and bolt, and putting it back together (almost) exactly as the factory designed it. That means stripping the entire body to bare metal so it can be blasted, sanded, plated, primed, and painted. Next comes tearing down and inspecting the OM602 inline five-cylinder diesel engine, five-speed manual transmission, and transfer case, replacing worn components where necessary. The braking system, fuel system, and suspension get full overhauls, with the latter receiving polyurethane bushings with eccentrics to compensate for the 1.6-inch lift.

“We go as far as fastening everything together with stainless steel hardware, rather than zinc-coated, so we can be sure everything is built to last,” says Bill Thomas, technical advisor and product development lead for EMC since the company’s founding in early 2017. “We think of this as a legacy lifetime vehicle. With the way these vehicles are painted, for example, it could last 50 to 60 years.”

Thomas is a veteran of the auto industry, having worked as a technician at Nissan and Infiniti before moving to Ferrari North America as a technical and business manager. He’s no stranger to vintage metal either, as he runs his own British car restoration outfit that specializes in Triumphs. “I am a real off-road geek though, too,” he explains, “whether it’s old Land Rovers, Nissan Patrols, or whatever else. But these G-Wagens are remarkable and just so overbuilt.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

His partner, EMC founder Alex Levin, also has a deep affection for the classic Mercedes truck. His father’s G-Wagen was the first car he ever steered, at the ripe age of 2, not long before his family moved from Belarus to the United States. Levin joins me for my test drive in the roads surrounding EMC’s garage in Frenchtown, New Jersey. It’s a dim, thick-aired day in late summer, with the occasional drizzle threatening heavier rain, but we commit to driving with the Wolf fully open so I can get the full experience.

The full experience, it must be said, is hysterically, wonderfully slow. Remember—restored though it is, we’re still dealing with a 2.5-liter, 93-hp diesel inline-five with a single overhead cam, lugging around a pile of seriously robust off-road hardware. And all of it is wrapped in thick steel. I find myself driving it like my old Beetle, flooring the gas pedal often and—because there is no tachometer—letting my ear decide when it’s time to shift. Terminal velocity is 75 mph, at which point any driver with mechanical sympathy or even the most remote sense of chill is going to back off and just accept that the destination will eventually arrive.

Why worry about it, anyway? Driving a classic G-Wagen is a downright good time. EMC’s suspension setup is firm but not as brutal as in default military spec, and Eibach springs with Bilstein dampers provide a relatively streetable ride. It even steers and stops better than we expected, though our test truck was on General Grabber AT2 rubber rather than the ever-popular BFGoodrich KO2s, which are hard to come by given the current supply chain struggles. Thomas daily drives his Wolf, though he and Levin recognize that the truck is a special-use vehicle for the majority of EMC customers, and very few will actually use it for demanding off-roading.

Whether it’s for weekend fishermen, hunters, or beach community residents who don’t need to use the freeway, a Wolf is a compelling excuse to unplug for a while, rest one hand on the big two-spoke steering wheel, and drive along with the wind in your face. The few concessions to modern life—the four-speaker sound system with either Clarion or Pioneer head unit, custom cupholders, soft-touch door-cards, and custom floor mats—do not sully the novelty of driving a military G-Wagen as much as they let you focus on the pleasant parts. The back-row bucket seats are surprisingly roomy, especially with nothing but open sky overhead. The ammo box between the two captain’s chairs is pretty sweet, too.

“The Wolfs are what they are, and they’re not what they’re not,” clarifies Levin, half-shouting to me from the passenger. “Nobody should expect to be taking conference calls from here, and if they do, they’re missing the whole point.”

First gear is straight ahead, with reverse up and to the left and the low-range crawler gear positioned down and to the left. It’s easy to figure out, and because this is a basically a tractor with four wheels and three fully locking differentials, the transmission is very forgiving. Clutch takeup is a bit high in the pedal travel, a bit like in most BMWs, and feathering requires a surprising amount of throttle. You really have to keep this motor on the boil, shifting often and well in advance of hills to maintain smoothness. With the additional shift lever to engage four-high or four-low it’s an engaging full-body dance to keep the G-Wagen trundling down the road. It’s this same conclave of man and machine that made Jeeps so delightful to WWII GIs they wanted to drive them all over the U.S. once they came home.

Levin is committed to preserving that sense of engaging simplicity, and part of that is limiting the options list. He’s against engine swaps, though he did do a few gas-powered or turbocharged builds early on. “We’re not selling a custom spaceship. There are not a lot of options, because I f***ing hate options, and they are not a profit center for us. As long as it doesn’t dramatically alter the build process we are happy to meet the customer’s needs.”

The order process usually begins with EMC’s online configurator. Once you’ve selected your paint color, interior color scheme, black or beige weatherproof roof (full soft-top and front-row bikini top are both included) and and choice of clear or amber light indicator lenses, there are precious few cost-added options to consider. The major ones are EMC’s custom bumper and winch ($2000), bull bar ($1000), and factory-design snorkel kit ($750).

Only until recently did Levin relent and start offering an automatic transmission option, for an additional $7500. The demand was simply too high, and the automatic now accounts for about 30 percent of orders. (Another factor was that some of EMC’s prospective customers could not physically drive stick, and Levin did not want to turn them away.) The torque-converter unit is a five-speed affair plucked from the 2009–12 S-Class, selected for its size, durability, fitment, and compatibility. EMC does its own Transmission Control Unit tuning to make the transmission work smoothly, and it can be customized for the buyer’s intended usage, but the automatic we drove did not feel totally sorted. Gear changes often came much later than expected, not to mention harsh enough when they did that the truck lurched a bit forward with each upshift. Levin assured me that kinks in this particular car were still being ironed out, and he showed me how he is able to alter shift mapping, shift feel, and other attributes directly on the fly via a small piece of hardware in the glovebox, but this predicament strikes us as just one more reason to stick with the manual.

Keeping the orders straightforward allows EMC to sweat more important details and fulfill orders with delivery within six months. These resto-modded Wolfs have been sent to France, Italy, and Japan, among other countries, and U.S. buyers hail from Florida, the Hamptons, Texas, Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Chicago, and Boston. A few Mercedes executives are even among EMC’s customers. Since the company finished its first build in 2019 it has overhauled nearly 80 Wolfs, and there are 80-100 unrestored and in reserve—enough for about 5 years of operations. “Every dollar that comes into this business has gone back into purchasing more unrestored inventory, so that this is a 10-year business rather than a 2-year business,” Levin explains. “We are structured to do this very precise thing, efficiently and quickly.”

Yes, a hundred-and-thirty grand is an objectively exorbitant sum, but buying a rusty Wolf for $30,000 and then spending just as much on parts gets you only about half way there before the restoration shop even prices out its labor costs. A no-expense-spared restoration of a military-grade G-Wagen is about as niche as it gets, but the appeal is real. You’d have to be flooring it in top gear, downhill, and benefiting from a tailwind just to pass a modern G-Class doing 80 mph of cruise-controlled smooth sailing on the highway, but it’ll be a whole lot more fun.