Media | Articles

Your handy 1964–67 Sunbeam Tiger buyer’s guide

“Versatile! Drag it! Race it! Swing with it!” read a print advertisement for the 1964 Sunbeam Tiger. That single ad laid out everything attractive about the Tiger, showcasing Stan Peterson’s Autocourse Tiger with slicks and Minilite wheels, Doane Spencer’s #55 road racing Tiger, and a scantily clad model atop the decklid of a Sunbeam Tiger in street trim, with full wheel covers.

The car on which the Tiger is based wasn’t “new” by any stretch of the imagination. The Rootes Group was building the unibody Sunbeam Alpine since Loewy Studios—and specifically Barney Roos—designed the Series I in 1959 on a Hillman Husky chassis. It sported a wishbone front suspension, a solid rear axle, and Girling front disc and rear drum brakes. The Tiger was a beautifully styled car that almost had the appearance of a two-thirds scale 1957 Ford Thunderbird, with its open grille, wide-set, hooded headlamps, and subtle tail fins.

But by the time of Series III production in 1963, the best its 1592-cc inline four-cylinder could muster was 92 hp, good for a tick under 100 mph, but by 1962 you could buy an MGB with similar performance for a lot cheaper. It became evident to executives at Rootes—most specifically, Brian Rootes, son of founder Sir William Rootes—that the Alpine needed more power. The Rootes Group, it must be said, wasn’t exactly an engineering powerhouse despite developing a commercial diesel engine on its own utilizing an innovative all-aluminum overhead cam engine in the Hillman Imp. That said, Rootes wasn’t in the position of developing a high-performance engine for use in a low-production sports car.

According to William Carroll in his book, Tiger, An Exceptional Motorcar, the Rootes Group looked for engine suppliers around the world. The company considered Ferrari to re-engineer its four-cylinder, banking on the good public relations that “powered by Ferrari” would bring, but the negotiations ultimately failed.

In October 1962, along with his teammate Stirling Moss, Formula 1 champ Jack Brabham piloted an Alpine to second place in the production class of the Los Angeles Times Grand Prix at Riverside. According to Carroll’s book, Brabham bent the ear of Rootes’ Competition Manager Norman Garrad, suggesting that a Ford V-8 would be just the ticket to propel the Alpine to international success.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

By 1962, Carroll Shelby already convinced AC Cars to build several AC Aces that could accept a V-8, and shoehorned Ford’s 260-cu-in V-8 in place, thereby cementing that car’s legacy in automotive history. In Sunbeam Alpine and Tiger: The Complete Story, Graham Robson noted that Garrad’s son Ian was the West Coast Sales manager for Rootes and President of International Automobiles Incorporated, the official importer of all Rootes vehicles. Ian Garrad lived close to Shelby American. He met with Shelby, who proposed that with $10,000, the Shelby American could fit a 260-cu-in V-8 in place in about eight weeks. “Well all right, at that price when can we start?” Brian Rootes asked. “But for God’s sake keep it quiet from Dad [Lord Rootes] until you hear from me. I’ll work the $10,000 (£3571) out some way, possibly from the advertising account.”

At the same time, another key player in the Shelby American orbit was involved. Ian Garrad simultaneously contracted with Ken Miles to build a prototype/feasibility study as quickly as possible. According to Robson, Miles got the princely sum of $800, a Series II Alpine, a 260 V-8 and a two-speed automatic transmission, with the instruction to put it all together as quickly as possible. In about a week, his cobbled-together car proved the concept that a V-8 powered Alpine was possible.

At the beginning of April 1963, Shelby began work on what would eventually be a production Alpine. By the end of the month, he had a 260-powered Alpine ready for testing. John Panks, director of Rootes Motors Inc. of North America wrote effusively to Brian Rootes about the prototype, suggesting that it was every bit as exciting as anything Jaguar had put together. “It is quite apparent that we have a most successful experiment that can now be developed into a production car,” he wrote to the bosses whose names were on the building at Rootes.

Shelby’s prototype was initially called Thunderbolt, and unlike Ken Miles’ hustled together car, it sported a four-speed manual transmission, also grafted from a Ford. At just 3.5 inches longer than the Alpine’s four-cylinder, length wasn’t an issue, especially with the Ford’s front-mounted distributor. The issue was width, and the Ford V-8 took all space that was available.

Despite all the work Miles and Shelby put in under the direction of Brian Rootes, Norman and Ian Garrad, and the encouragement about the car’s potential from John Panks, the last word on development was still in Lord Rootes’ wheelhouse. The word at the time: He was not happy about it. Nevertheless, he reluctantly agreed to have a Shelby prototype shipped to England, which he drove himself.

Whatever reservations he had about the project appear to have dissolved on that evaluation drive, because Lord Rootes quickly placed an order for 3000 260-cu-in V-8s, according to John Gunnell’s Standard Catalog of British Cars. William Carroll claims that it was the largest order of engines Ford had ever received outside of a government contract. Lord Rootes not only wanted the car in production, he wanted it ready for the 1964 New York Auto Show in eight months time.

Since American consumers were the target audience for the Tiger, Shelby assumed he’d get the contract for building the cars, just the way he had with AC. Instead, he got an undisclosed percentage of every car built without performing any further work, which must’ve been the greatest outcome Carroll Shelby could have wanted. Rootes had no capacity to build a low-production car, so it farmed out the work to Jensen, which turned out 14 Tiger prototypes using the Alpine Series IV shell by the end of 1963.

Mk I (1964 to August 1965)

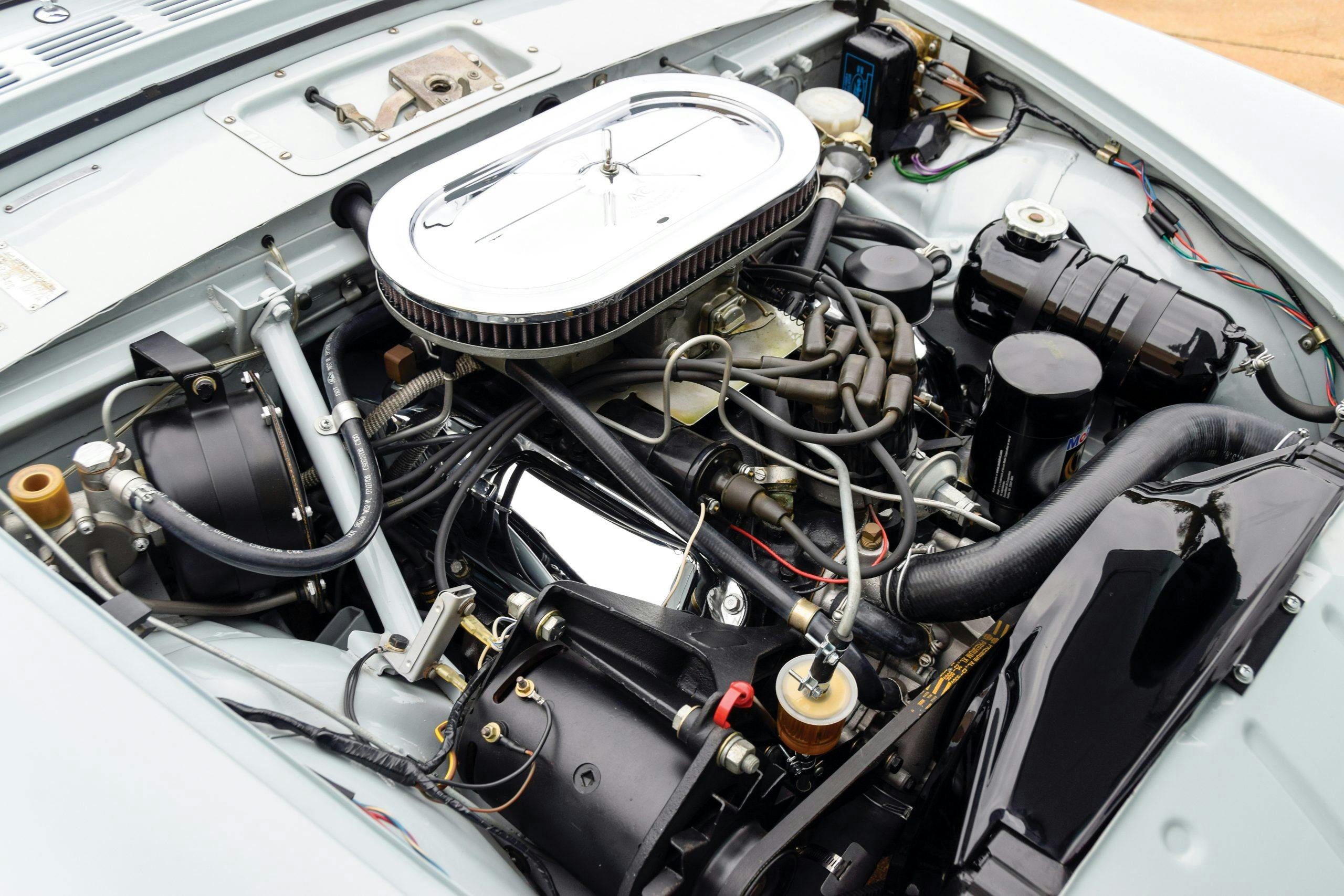

The Sunbeam Tiger went into production in June of 1964 with a few differences from the Alpine Series IV upon which it was based. The VIN starts at B947XXXX, and the bodies came from Pressed Steel in Oxfordshire with the engines and transmissions sourced from Ford. According to R.M. Clarke in Sunbeam Tiger Limited Edition Extra, 1964–1967, the first order of business was to bash the firewall of the newly primed and painted bodies with a sledgehammer to allow the engine to slide into place. The Tiger even had an access hole cut in the driver’s side footwell to allow the #8 spark plug to be changed.

There were other (less violent) modifications as well: The steering went from recirculating ball to a modern rack-and-pinion setup. While Alpine’s battery location was inside the cabin behind an access panel, the Tiger’s battery moved to the trunk. This allowed for an SU electric fuel pump in that location, which subsequently provided room for the dual exhaust. Inside, all Tigers had with a wood dash and wood steering wheel, which justified the Tiger’s elevated price tag. In the trunk, the spare tire on an Alpine stood up, but on the Tiger, it laid flat on the floor. Outside, the only visual cues were the “Tiger” script on the front fenders, the V-8 callout just below it, and dual exhaust outlets. The Mk 1 featured a grille opening with a horizontal bar and a Sunbeam emblem in the middle.

All Mk I Tigers have a 164 hp, 260-cu-in Ford V-8, with modifications to jam it into place under the hood, including a remote oil filter. All of these cars were built with a two-barrel carburetor, but that’s really only part of the story. Most owners placed orders from the “LAT catalog”—for Los Angeles Tigers, a subsidiary of Ian Garrand’s International Automobiles Incorporated—with everything from hotter cams, Edelbrock intake, and a Holley four-barrel carburetor. Those parts would be installed at the port, either in Long Beach, California or Long Island, New York.

The earliest Tigers used a Ford T-10 sideloader four-speed transmission. That quickly gave way to a close ratio T-170 toploader, and all Tigers used a solid rear axle with a Dana 44 differential from the factory.

Online resource Tigers United suggests that Sunbeam built 3763 Mk1 Tigers between April of 1964 and August of 1965. Robson’s book suggests that all but 56 of the cars came to the United States, with an MSRP of $2898.

Mk IA (August 1965 to February 1966)

Mk IA cars have VINs beginning with B382XXXXXX. There’s really no “official” Mk IA Tiger, as the designation unofficially described cars built using the Sunbeam Alpine Series V as a foundation. MK IA Tigers had a vinyl top boot rather than a metal cover, according to Sunbeam Specialties Inc., which also provides an outstanding guide to decoding Tiger chassis numbers.

The most noticeable difference is in the doors: Mk I cars had rounded corners on the door bottoms, where Mk IA’s that arrived in 1966 had a much sharper lower trailing edge corner. That same sharpening of corners is also evident in the hood and the trunk lid. According to Tigers Unlimited, Sunbeam built 2706 Mk IA Tigers between August of 1965 and early February of 1966.

Mk II (December 1966 to June 1967)

The major difference between the Mk IA and Mk II cars was the engine, which upgraded the 260-cu-in V-8 to Ford’s 289-cu-in V-8. The 3000 260s that Rootes purchased allowed the company to continue producing a 260-powered Tiger through early 1966. The Mk II wouldn’t reach production until December of 1966, and only lasted seven months into June of 1967. All units were destined for the United States. The bigger V-8 helped the Mk II’s performance, dropping its 0-to-60 time to 7.5 seconds, and increased top speed to 122 mph.

What eventually killed the Tiger wasn’t sales or performance, it was corporate ownership. By mid-1964, after a devastating strike and the expense of launching the Hillman Imp, Rootes Group was in deep financial trouble. Chrysler came calling, hoping to build a presence in Europe, eventually purchasing a £12 million stake in Rootes Group.

That stake didn’t equal controlling interest in the company, but it put a lot of pressure on the management team, especially when Sunbeam’s halo car featured power from its biggest competitor. Subtle changes in the Mk II’s advertisement and the car itself became evident. Print ads no longer touted “Powered by Ford”, instead the language shifted to “an American V-8 powertrain.” The callouts on the fenders no longer said “260: Powered by Ford,” and never indicated that the engine was Ford’s familiar 289. They instead indicated the more generic “V8”. Below that badge, behind the wheel opening, later Mk IIs had the Chrysler Pentastar emblem.

Other minor changes included the grille and the “Sunbeam” and “Tiger” emblems. In the earlier cars, “SUNBEAM” was spelled out in block capital letters across the hood and decklid. On the Mk II cars, “Sunbeam” became a smaller script, affixed to the left side of the hood, with a “Tiger” script mounted to the right side of the rear decklid, topped with the SUNBEAM brand in a parallelogram emblem just above it.

Tiger Mk IIs have VINs beginning with B382100XXX. In all, Sunbeam Specialties notes that just 536 Mk IIs were produced.

Before You Buy

It’s important to know whether you’re buying a legitimate Tiger, or an Alpine with a V-8 jammed in the engine bay. The Sunbeam Tiger Owner’s Association will authenticate a Tiger unibody. The certificate won’t mention much more than the fact that the unibody itself was originally a Tiger, but it’s some means of understanding the car’s authenticity.

There’s a lot to be gleaned from the chassis number, even if the car hasn’t been authenticated. The chassis number has two groups of suffixes. The first group includes “GT,” indicating a hard top and tonneau with no soft top and an upgraded interior, and “OD” for an overdrive transmission. The second suffix group is comprised of five letters that indicate the car’s intended destination (“H” for “home market,” “R” for “right hand drive export” or “L” for “left hand drive export,”) a second “R” signifies the roadster body style with a soft top, and any special order information (“O” for standard, “X” for non-standard, “P” for “Police specification”). Finally, all Tigers will have chassis numbers that end in the letters “FE” for “Ford Engine.”

It’s difficult to find a Tiger that hasn’t been modified from factory specification in at least some degree. Almost all units had their two-barrel carb and intake removed in favor of the Edelbrock/Holley induction kit offered by the LAT catalog, for example. Traction bars—both offered by the LAT catalog and the aftermarket—are nearly universal, in order to prevent the axle hop that was endemic to a 260-cu.in. V-8 powering a leaf-sprung rear axle.

The LAT catalog offered traction bars from Traction Masters, which are still sold today. Traction Masters suggests that the Sunbeam Tiger was “factory equipped” with these bars, but that depends on one’s definition of the word “factory.” It’s true that most Sunbeam Tigers are equipped with those bars when they hit the ports in L.A. and New York, but not all of them. A beautiful 1967 came up on BaT in February of 2021 wasn’t equipped with traction bars, for example.

This is a British unibody vehicle, so all the concerns about rust apply: Rockers, floors, and trunk floors are the structure of the car, and they will rust to pieces. Look for rust in the common areas like lower fenders, lower doors and floor supports. Outfits like Classic Sunbeam offer replacements and repair panels, but get the car on a lift to see what’s precisely going on underneath: You can quickly get into reconstruction that would overshoot the cost of a better car.

On the plus side, the 260 and 289-cu.in. V-8s are backyard-mechanic simple, with parts available everywhere. There are some differences between a Tiger V-8 and a Mustang. Tigers had remote oil filters and electric fuel pumps, but all the internals are identical to Ford vehicles. Transmissions are similarly common. The early toploaders and later sideloaders are plentiful and easily rebuilt anywhere in the United States. The Saisbury-sourced Dana 44 differential is also about as stout as you’re likely to find in a British sports car.

Loads of Tigers have improved suspensions, including Koni adjustable shocks, better springs, thicker roll bars and panhard rods in the rear. Wheels are also so universally swapped that it’s a bit of a shock to see a car with its original steel wheels and full wheel covers. Having stock wheels versus Minilites doesn’t seem to harm the value a bit.

All Tigers were negative ground, while the Series IV Alpines were often still positive ground. The Tigers featured alternators and were generally better off electrically. That said, no 55-year-old wiring system is going to last forever. Wiring harnesses are available for cars with alternators. If your Sunbeam has a generator, you’ll need to do an alternator conversion at the same time.

Sunbeam Tiger Values

Sunbeam Tigers aren’t cheap by any means, but if you’re into the Ford/British Car/Carroll Shelby/Ken Miles connection, they’re a lot cheaper than a Cobra. According to the Hagerty Valuation Team, Tiger values shot up considerably around 2013, more or less coinciding with the passing of Carroll Shelby. Values then leveled off in 2016, and trended downward afterward. Median #2 values went up 161 percent between May of 2012 and May of 2016, but since then, the values have dropped 26 percent.

The most expensive Tiger sale on BaT occurred in October of 2020, which had significant racing history, and had participated in vintage racing events at the Goodwood Revival and Sonoma Historic Motorsports Festival. It sold for $160,000. Road-going Tigers generally sell for a lot less. Project cars sell in the $7000 to $15,000 range. Solid #3 cars are anywhere from $40,000 to $50,000. The sweet spot for cars between #2- and #3-condition seems to be between $60,000 and $70,000 over the last few years. The Hagerty Valuation Team pegs the value of a #2 car at $74,000 for a Mk I, $83,200 for a Mk IA, and a big jump to $137,000 for the rare Mk II. Add about $5000 for a hardtop in any generation.

The median quoted value is $61,800, which is only up one percent over the past five years. The number of quotes is down five percent over the past 5 years. Baby boomers who fantasized over the opening credits of TV’s Get Smart quote 69 percent of Tigers, while making up 37 percent of the market overall. Gen-Xers quote 16 percent of Tigers and make up 32 percent of the market overall. Pre-boomers quote 12 percent of Tigers and make up 6 percent of the market overall. Millennials quote 3 percent of Tigers, making up 19 percent of the market overall.

Tigers purchased prior to 2012 were a smoking deal. That period ended once the values spiked, but it appears there’s a huge generation gap in interest, which should keep the prices flat for a while, if not put some downward pressure as more shake loose from older collectors. Regardless, the Tiger is a significant part of Anglo-American performance history, one that doesn’t command the insane prices of other cars that experienced exactly the same mid-1960s trajectory. If you want one, you deserve it to yourself to get one.

Probably said many times before to you. No one bashed the transmission tunnel of the car with a sledge hammer. The Alpine tunnel was never fitted since the Tiger bodyshell was unique. A new pressing was installed by Jensen. If ever you ever seek to refresh this page I’d be happy to help. I’ve written about the Tiger for 25 years. Thanks Sunbeam Tiger Club (UK) – Editor. Former trustee of the Rootes Heritage Centre in Banbury, England.

Hi Graham, I wanted to introduce myself. I purchased the GP 3 car from the Gruys estate. I have developed a friendship with Gordon England on the restoration process of this car. Much debate on the Nor Cal side and a lot of assistance from Gordon and Hollie Orifino (Chris Gruys wife) in the restoration process. I have been in contact with Chip Fudge (Monster) for a reunion hopefully in Monterey in 2024. I joined your club at the advisement of Gordon and would appreciate any input you may have. Thank you and take care.

My cousin had one of these, not sure of the series, but it was a thrill as a kid to ride in, all wind and engine noise. Being so low, and topless, apparently it was hard to see in traffic, he got hit so many times that we called it, “the runover car”. He eventually sold it for something safer. HIs taste in cool cars lived on, with his last sports car purchase (new from the dealer), a final year air cooled Porsche widebody.