Media | Articles

How Henry Ford advocated for public road building—until he wanted to join a fancy camping club

While it’s easy to think of the explosive growth of the automobile industry in the early 20th century as the natural expansion of an inevitable market, the historical truth is that early auto and truck sales were hampered by the lack of good roads, particularly between cities. Even in urban areas, what we today call pavement was then a relatively new thing. Asphalt paving wasn’t introduced until after the Civil War and costs prevented it from replacing cobblestones or block pavers until the 20th century. The first concrete road in the world was a stretch of Detroit’s Woodward avenue, poured in 1909 a year after the Model T was first built in Henry Ford’s factory on Piquette Avenue, just a few blocks off of Woodward. Between cities, though, there were hardly any decent roads to speak of, and only a fraction of them were “improved”, which typically meant a dirt road that had been graded and those were mostly close to cities and towns. Most of those dirt roads were rutted and bumpy when dry and often impassable when wet. Crushed and steam-rolled gravel roads between cities were rare and asphalt and concrete roads were almost nonexistent outside of cities.

As it happened, the push for good roads did nome come from automakers or motorists, but rather bicyclists. (There is a reason why early bicycles were known as “boneshakers”.) John Dunlop didn’t patent the shock absorbing air-filled pneumatic bicycle tire until 1888. The League of American Wheelmen founded the Good Roads Movement and the Good Roads magazine.

The growing popularity of the automobile helped fill out the constituency of those who wanted better roads. In 1912, an entrepreneur named Carl Fisher had the idea of constructing a graveled transcontinental road that he initially called the Coast to Coast Rock Highway. Fisher said it would cost $10 million to build. He proposed that the money would come from car and automotive accessory companies donating 1 percent of their revenue to pay for materials with communities along the route paying for construction equipment. Lest you think that he was some kind of con artist, Carl Fisher was a rather successful businessman and famous in his day, having built the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, paved it with bricks and started the Indianapolis 500 race. Later, he would invest in some swampland in Florida and turn it into Miami Beach.

Fisher was able to get industrialists Frank Seiberling, who ran Goodyear tires, and Henry Joy, who headed Packard Motor Car Company, to sign on to the project, which was renamed the Lincoln Highway Association after the 16th President. The schedule planned for completion in time for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition, to be held in San Francisco, the western terminus of the Highway, whose other end started in New York City. Unfortunately for the Lincoln Highway Association, the one industrialist whose support would likely have guaranteed its success, Henry Ford, did not believe private funding would be sufficient for the country’s highway needs. Ford instead wanted counties, states, and the federal government to support road building, and he devoted public relations and lobbying efforts toward that end—much as he would later do regarding airports for his Ford Tri-Motor airplanes.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

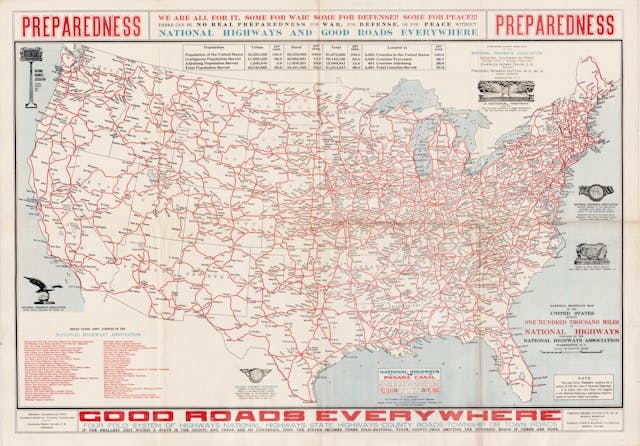

Instead of backing the Lincoln Highway, Ford was a supporter of Charles Henry Davis’ National Highways Association, founded in 1911 with the slogan “Good Roads Everywhere”. One of the NHA’s first projects was publishing a map of its proposed system of National Highways, a 50,000 mile network of roads that Davis characterized as “a broad and comprehensive system of National Highways, built, owned, and maintained by the National Government.” The association cited defense and military purposes to promote its system of national highways, presaging one of the Eisenhower administration’s rationales for starting the Interstate Highway system in the 1950s. An urban legend in the 1960s said that the gentle curves on the Interstates were designed to allow trucks towing long ballistic missiles to travel at high speeds without slowing down. While that may or may not be a legend, but at least one academic paper says that Interstate overpasses were indeed specified high enough to allow trucks carrying missiles underneath them. The Interstate Highway System today has 46,876 miles of roadway, within 10 percent of Charles Davis’ proposed National Highways system. Many of the Interstate Highways follow pretty much the same routes as Davis’.

The Vagabonds, glamping, and “greasing the wheels”

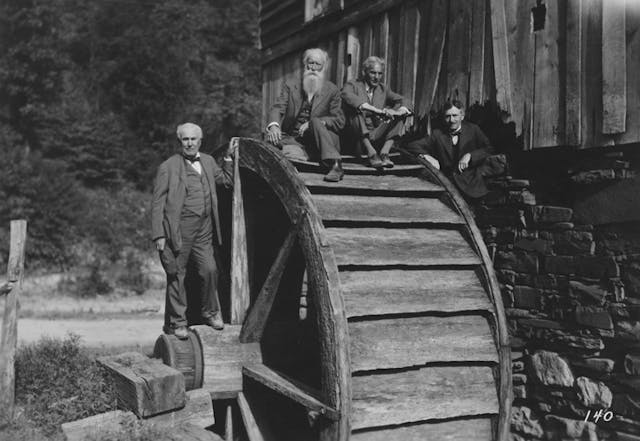

Henry Ford grew up on a farm and had a great love of the outdoors, which he advocating accessing by means of the automobile. By 1914 Ford Motor Company was selling over 200,000 Model Ts a year, and more roads were needed to keep pace. That year, Ford and naturalist John Burroughs decided to join Thomas Edison at the inventor’s winter home in Ft. Myers, Florida. Nearly the entire town of 3000 people turned out to greet them at the train, along with 31 Model T owners. While Ford and Edison are still household names today, it should be pointed out that conservationist Burroughs was one of the best-selling authors in his day, with his books selling millions of copies, and was almost as famous as the other two men. Edison organized a camping trip to the Everglades that was originally going to be men only but Mrs. Edison, Mina, insisted on going. So it became a family outing, with Clara Ford and the Ford’s son Edsel coming along. Henry made sure the campers were refreshed with Poland Spring water he had shipped from Maine, and Edsel, then 21 years old, recorded the trip on his camera. The men enjoyed their developing friendships and time away from the spotlight on their day to day lives.

Burroughs was originally skeptical about the automobile, particularly gasoline-powered cars, and wrote essays about the “befouling incursions of the automobile” into his beloved nature. Henry Ford was a bird watcher and a fan of Burroughs’ books. Dismayed by Burroughs’ essays, in a bit of personal lobbying, Ford sent the writer a Model T as a gift hoping to persuade him that the personal automobile made it possible for people to visit and enjoy nature. The Model T sparked a friendship between the two men. Burroughs found Ford and Edison to be intelligent and entertaining companions.

Then World War I broke out. Industrialists like Ford, Edison, and tire magnate Harvey Firestone became concerned that the war would disrupt the importation of natural rubber. Ford and Firestone were already business associates, Firestone supplying Ford with tires and other rubber components, as well as good friends. Their families were so close that Bill Ford Jr., the chairman of Ford Motor Company, is the great grandson of both Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone. The three men met at the Pan Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco, where Edison was being honored and, on a whim, decided to visit botanist and plant chemist Luther Burbank at his lab in Santa Rosa about 55 miles north of the city. Burbank was famous for finding new, practical uses for plant chemicals. Edison was intrigued at the possibility of finding a domestic plant source for natural rubber. The three men enjoyed the excursion so much that Edison proposed they go camping the following year.

In 1916, Firestone met Edison at the latter’s factory in New Jersey, where the two men proceeded to Burroughs’ summer home in the Catskill Mountains. Firestone and Edison camped in the writer’s apple orchard and though the aging Burroughs initially preferred the comforts of his home, he was persuaded to join the other men by what he described as their “Waldorf Astoria on wheels”-level cuisine. Harvey and Tom weren’t exactly camping out of backpacks. Though Ford was unable to join them, the three men set out on a two week trek to the Adirondack Mountains, roughing it with a staff of a cook and five servants. Burroughs taught the campers about nature and Edison took plant samples, looking for sap-producing plants that might be used to make rubber. Burroughs came home rejuvenated.

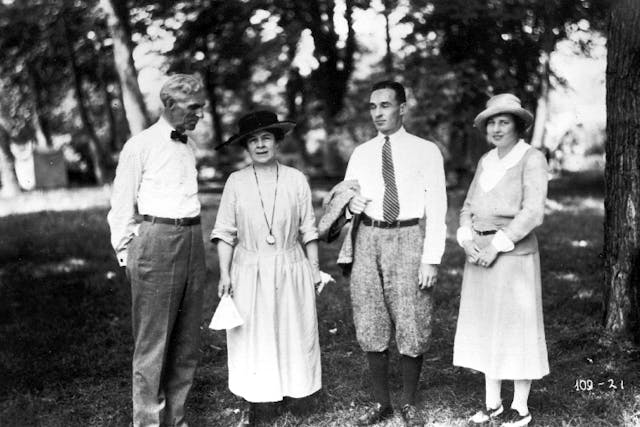

Their next trip was delayed by the war, but in 1918 Ford was able to join them, with an even larger entourage, and the four men started going on annual camping trips to mountains and wilderness areas in the eastern United States. They were frequently joined by family members and a variety of notables like President Warren G. Harding. Though Burroughs died in 1921, these so called “Vagabonds” camping trips would continue until 1924.

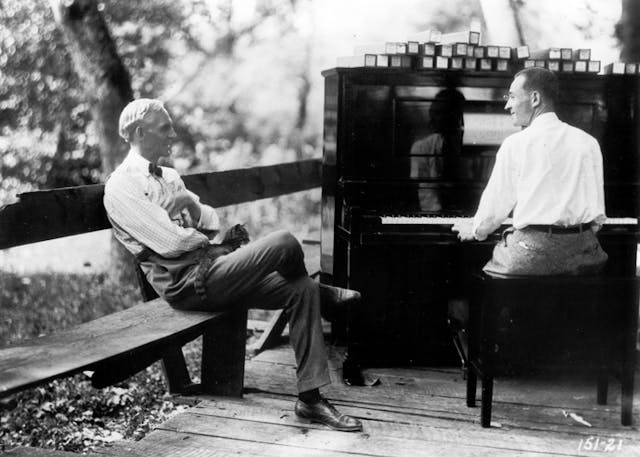

Ford and Lincoln vehicles, as well as heavier trucks, were customized to carry the Vagabonds’ gear. Some say the crew invented “glamping” (read: luxury camping). Ford’s household staff took care of the bushcraft so that the Vagabonds could sit around the campfire enjoying the wilderness. One expedition even included a player piano.

The 1919 trip had a caravan of 50 vehicles, including two said to be customized at Ford’s personal direction, a kitchen car with a stove fired by gasoline and built-in icebox, and a White truck with storage for tents, cots, chairs, and even the electric lights used at the campsites that were powered by a generator that Edison made. At each stop, the staff would set up a large round table, with seating for 20 and a giant, built-in Lazy Susan to pass the food around such a large gathering. Employees would also set up individual ten-foot square canvas tents, with cots and mattresses and personalized with the Vagabonds’ names, and prepare the firewood for the campfires (that Henry Ford didn’t himself chop). According to Burroughs’ account, Ford also served as chief mechanic for the Vagabonds, fixing any machinery that needed repair.

We know that Ford liked to chop wood because, savvy about publicity and eager to shape his public image, he made sure to have teams from the Ford Motion Picture Laboratories and Ford Photographic Department to record the camping trips for posterity and not so incidentally create free content for newspapers and theater operators. There seems to have been some grumbling that the publicity was hampering their privacy, and Edison took to guiding the Vagabonds on back roads when crowds started to gather to watch them drive through towns. All four men, though, understood the value of publicity.

As a matter of fact, regarding the publicity that the Vagabonds received, many transportation historians think that Ford had more on his mind than enjoying fresh air and the great outdoors. Perhaps, say, the Vagabonds’ expeditions were actually an important part of a publicity campaign to promote more government road construction? The publicity the Vagabonds received also helped popularize overland car camping and the decreasing price of the Model T gave birth to what hoteliers ruefully called “tin can travelers,” budget conscious tourists. The increased number of people using their personal automobiles for leisure travel was another group that wanted better roads. Directly or indirectly, the Vagabonds shaped public opinion about many things, including the famous participants’ image as regular folks, the practicality of the automobile for long-distance travel, and the need for better roads.

Automakers, tire companies, and their customers weren’t the only people interested in better roads. Farmers and rural politicians were clamoring for better roads to take crops to market, using the slogan “Get the farmers out of the mud!” Washington listened, and the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 was passed, creating the Federal Aid Highway Program which in 1919 started to fund state highway agencies with matching funds for building roads.

Refusing to take “no” for an answer

Although Henry Ford was a big supporter of government road building, there was one government highway that Henry literally stopped dead in its tracks so he could gain membership to a private club. It’s a clear example of Ford’s relentless obsession with power in all senses of the word, willingness to throw around his weight, and (ultimately) short attention span.

To give you an idea of how much power and influence Henry Ford personally had, Michigan’s Public Service Commission granted Ford, a private individual, the right of eminent domain to seize land adjacent to dam sites in Michigan for his Village Industries project. Eminent domain is a monopoly generally reserved to governments. That the state of Michigan would take the extraordinary step of granting that power to a private person shows the extent of Henry Ford’s political and economic might.

Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company didn’t just own thousands of acres of land in southeastern Michigan. Ford had massive land holdings in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, more than a half million acres of pine and hardwoods he needed to produce the wood used to produce his cars. While we think of cars as being made of metal, it’s estimated that the manufacture of one Model T used about 250 board feet of lumber. Wood was used for body frames, wheel spokes, firewalls, dashboards, component housings, and the crates for all the parts.

In the U.P., Ford had sawmills in Alberta (most recently a lumbering museum operated by Michigan Tech University), and Kingsford, near Iron Mountain, where the mill manager, E.G. Kingsford, developed charcoal briquettes from wood waste. If you think being “sustainable” is a new thing, Ford’s Kingsford facility had a chemical plant that processed wood waste into acetate of lime, methanol, charcoal, tar, creosote, heavy and light lubricating oils, and fuel gas. All of those products were used either in house or sold commercially.

Lest you think that the Kingsford “mill” was a small lumberyard, it was a large industrial operation, including a body shop that assembled Ford “woody” station wagon bodies. During World War II, the factory produced military gliders. The factory also produced almost all of its own furniture, including all of the tables and chairs in the company lunchroom.

Ford also bought the entire town of Pequaming, on Keweenaw Bay, from its founder, Dan Hebard and turned it into a factory town. The transaction included a 14-room lakeside Southern style bungalow Hebard had built as a private lodge to please his wife, a southern belle, along with land adjacent to the nearby Huron Mountain Club. Hebard moved to land on the Pine River, in the Club’s holdings and Henry and Clara Ford began using the bungalow as a vacation home.

Ford believed in vertical integration and was heavily invested in the U.P. He built a large hydroelectric facility on the Menominee River to power the mill in Kingsford (and gardens to beautify the grounds). He also bought the Imperial Mine and opened the Blueberry Mine near Ishpeming to supply his foundries with iron ore. He had the Ford Railroad constructed between the towns of L’Anse and the Cliff River to service his logging operations, including the 300,000 acres Ford bought in 1922.

Henry Ford wasn’t just financially invested in the Upper Peninsula. He seems to have genuinely loved the region. It was in 1917 that Ford first tried to join the Huron Mountain Club, unsuccessfully, even though he was by then wealthy and prominent enough to have run for the U.S. Senate that year. Still somewhat secretive today, the Huron Mountain Club is a private reserve occupying about 20,000 acres of timberland and lakes in the Huron Mountains, a small chain that rises to about 2000 feet on the east side of Keewenaw Bay, part of Lake Superior. Michigan is generally flat but the Hurons have some of the highest elevations between the Rocky Mountains and the eastern mountain chains. The Upper Peninsula is also not very large and it’s surrounded on three sides by Lake Superior, Lake Huron, and Lake Michigan. With even modest elevations, their watersheds mean lots of rivers and waterfalls. There are over 200 named waterfalls in the U.P., which has some of the most spectacular scenery in North America.

When I said that the Huron Mountain Club was private, I meant private, as in gated roads, guard shacks, and year-round security for something that is 600 miles from the nearest major cities, Detroit and Chicago. After over a century, with a few small exceptions, the only people who have been inside the Huron Mountain Club have been members, their guests, and employees of the club. The region of the Hurons is generally regarded as the most rugged wilderness in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, already one of the most rugged areas of the United States. There is still not a single paved road today within the 1000 square mile area. An ideal place for wealthy folks that want to enjoy the scenery in privacy, one would think.

The Club was founded as a “shooting and fishing club” in 1889 by John Longyear, a lumber baron, with wealthy backers in Marquette, Michigan, Detroit, and Chicago. Longyear planned it as a moneymaking operation, hoping to charge people passage to get there on his steam boat, and perhaps even build some kind of resort on the Lake Superior coast similar to the resorts on Mackinaw Island and the northern coast of Lake Huron. The concept of bringing vacationers en masse to the club would prove to be ironic—more on that later. Longyear’s original facilities meant some rough living but by the roaring twenties, the Club had become an exclusive retreat for the very wealthy, with “cabins” larger than many middle class homes. Staff included chefs, waiters, and waitresses, while members brought their chauffeurs, maids, and butlers, to make roughing it as comfortable as possible.

The club limits itself to 50 primary members, who are allowed their own cabins on the site, and 80 associate members, who can hunt and fish there but don’t have cabins. The only way you can become a member is by being voted in by current members after one has resigned or died. It was exclusive then and it’s not cheap to belong today. Those members have to cover a property tax bill that’s close to $2 million these days. It likely costs about as much to be a Huron Mountain Club member as it does to belong to an exclusive country club.

As mentioned, Henry and Clara first tried to join in 1917, but the official history of the club says that Ford’s public image and fame concerned members that his membership might bring unwanted attention and publicity. Also, Henry was exceptionally wealthy and powerful and perhaps members thought he would make a caricature of their own wealth and power. Either way, Henry found a way to leverage his power to gain membership—and it all had to do with public road building.

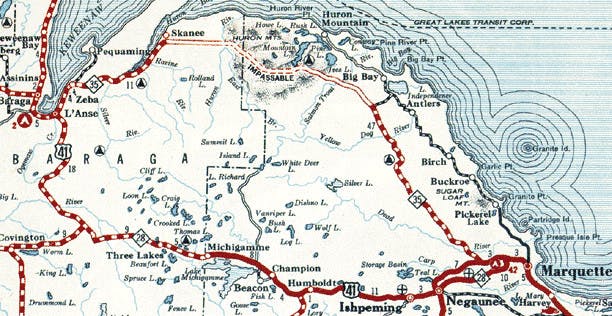

When Michigan’s state trunklines were first laid out and built in the nineteen teens, highway planners deliberately avoided running them along the Great Lakes shorelines, likely for winter driving safety. Later, though, the State Highway Department decided to let motorists enjoy some scenery and started laying out routes for shoreline roads on the coastlines of both Upper and Lower Peninsulas. US-2 along the north shore of Lake Michigan and US-23 on the Lake Huron shore were early examples. In the late teens, the area of the Huron Mountains was still only served by logging roads and unimproved two-tracks. A new trunkline, designated as M-35, was routed from near Negaunee west of Marquette, northwesterly through the Huron Mountains, and then southwesterly along the Keweenaw Bay to L’Anse. The eastern leg was completed in 1926 and the western leg by 1932. A steel bridge crossing the Allegheny River upstream from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was purchased, disassembled, and installed over the Dead River east of Negaunee, but the middle section through the Hurons was still marked on official state maps as “Impassable”.

Three things turned in Henry Ford’s favor regarding the Huron Mountain Club. Along with outdoor enthusiasts, Club members opposed the completion of M-35. A real estate developer from Detroit owned some nearby property in northern Marquette County, not far from the club. Members feared that the new road would expose the wilderness to harm, and maybe they also thought that a resort hotel nearby might make their own holdings less exclusive. (Considering Longyear originally developed the rustic property with an eye towards steamship passengers, there’s a certain irony to this logic.)

Second, in 1926, Dan Hebard, who had personally benefited from Ford’s wealth, was elected the new president of the Huron Mountain Club and one of his first acts as executive was to change the rules for membership. Originally, the membership at large voted on admissions and four “no” votes meant rejection. Hebard changed the rules to put the decision in the hands of club directors and only one “no” was needed to block election.

Finally, the Michigan Attorney General issued an opinion that said that if two-thirds of the property over which a road would pass was owned by people who opposed the road, that would be sufficient to overcome eminent domain and the road would be blocked. Unfortunately for the club members, the road only crossed two 40-acre parcels of their land, not enough to stop the road. Fortunately for Ford, there was some land near Mountain Lake that was available for his purchase and it made up more than two-thirds of the property that the planned route crossed. Ford, ever the savvy operator, bought the land and indicated his opposition to the road—perhaps the only highway construction Henry Ford ever opposed. In 1928, the road was rerouted to skirt the Huron Mountain Club property and in 1929 Henry Ford was voted in as a primary member.

Ford had his favorite architect, Albert Kahn, design a white pine log cabin on club property that cost as much as $100,000 to build in 1929, which works out to more than a million dollars today. The cabin still apparently exists, but because of the very private nature of the Huron Mountain Club you can’t visit it like you can the Ford Bungalow in Pequaming (available for rental by groups up to 16, should you want to sleep where Henry and Clara slept).

For all that work, though, Henry didn’t even get to enjoy his membership in the Huron Mountain Club for very long. Clara is reported as having been “unimpressed” with the cabin—perhaps the bungalow in Pequaming was more to her tastes. The Fords let their membership lapse soon afterwards.

The former M-35, now County Rd 510, still skirts the Huron Mountains, and the still very private and secluded Huron Mountain Club is still only accessible by some of the gnarliest roads in the state. That’s all because a man who helped persuade the federal government and states to start funding highway construction subsequently used his personal power to stop a public road from being built, just so he could join a club that he quit soon afterwards.

A really fascinating, detailed and well written article. I’m learning more about US car dependency and this provided a vital piece of the puzzle- thanks for sharing it with the world.