Media | Articles

Executive decision: Audi 80 vs. BMW 3 Series vs. Mercedes 190E

If you wanted to identify a point in time where BMW and Mercedes well and truly squared up to one another and set out to build the world’s greatest affordable executive sedan, you would probably end up at the start of the 1980s.

Editor’s note: This feature originally appeared on Hagerty UK, which should explain the steering wheels on the right-hand side of these cars. We’ve edited the story slightly for spelling and clarity, given the primary audience here in North America. Enjoy!

It was an upwardly mobile era, one when drivers desired more than a GLX or Ghia version of their company Cavalier or Sierra. BMW and Mercedes sensed as much. By 1982 the new E30, the second-generation 3 Series, and W201, Mercedes’ first compact sedan, were launched to shake up a lucrative part of the car market. Not long after, Audi would respond with the B3 version of its 80.

Since then we’ve witnessed four decades of progress built on many more decades of honing and shaping of image and ethos, imbuing each car’s steel, aluminum, and plastics with cast-iron appeal. But to understand what has changed and how, there was only one thing for it: bring all three cars together again.

Each carmaker has refined its vehicle down to a fine art, for a start. All are incredibly capable in any way you’d care to mention, but you could probably write a believable group test verdict without stepping foot in the latest variant, such is their familiarity. The BMW will be the driver’s choice, the Mercedes bristling with S-Class hand-me-downs, and the Audi dynamically colorless but still pleasant to live with thanks to its impregnable build.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Stifle another yawn as you realize that, like particles floating in the vacuum of space, all three are drawn steadily closer to homogeneity with each generation. Mercedes and Audi attempt to match BMW for driver appeal, Audi and BMW seek Mercedes’ levels of technology and comfort, and Munich and Stuttgart both home in on Audi’s quality control. An Audi is a BMW is a Mercedes? Pick a badge and go.

And if you think that sounds difficult to separate, just wait until they’re all electric too.

The revelation from driving around in a 1988 Mercedes-Benz 190E 2.0, 1989 BMW 318i and a 1991 Audi 80 2.0E was how wildly different in character and ability each car turned out to be. Cars of similar size, competing in a similar segment and priced at a similar level (the 190E was a touch more expensive in its day, but we’ll get to that), yet diverse in approach, execution and feel.

Upwardly mobile

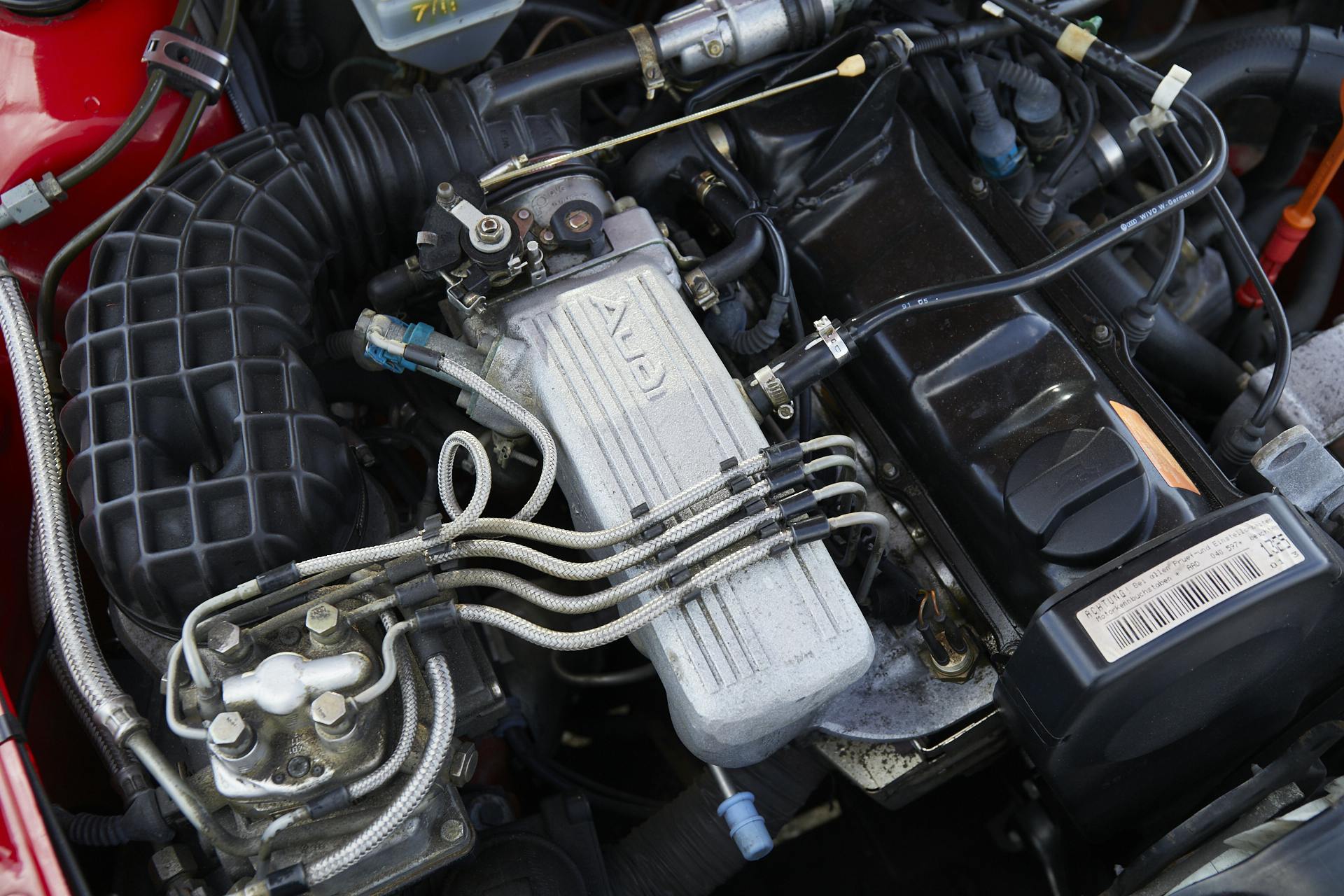

80 first, an escapee from Audi UK’s extensive fleet of heritage vehicles, specified originally in SE trim and then fitted with the dealer Sport pack. The latter stops short of the proper Sport model’s more enveloping seats and firmer suspension, but got a set of six-spoke alloy wheels pretending to be split-rims, and a rear spoiler that does indeed spoil the 80’s smooth lines but looks appropriate against the wheels and bright red paintwork.

It’s the newest car here, and the freshest form having debuted in 1986, but the detailing appears a decade ahead of the E30 and 190E, despite each arriving only four years prior. The 80’s shape is bar-of-soap slick, with smooth window seals and door handles that sit completely flush with the body, while lights, grilles and bumpers also cosy up to adjacent panels. It’s not hard to see how the shape, only lightly facelifted in 1992 to become the B4 generation, endured until 1996 in drop-top form.

The interior is more of-its-time, but that’s not meant to be disparaging. It’s just fairly plain, fronted by a shallow dash, relatively upright windshield and a modern-feeling high shoulder line, the latter contrasted with details like the Blaupunkt cassette player and airbag-less steering wheel that place it squarely back in the pre-digital age. As does the tweed trim, soft and yielding despite a curious lump in the seat back (must be one of those Vorsprings I keep hearing about). After around 67,000 miles though, it’s as solid as the stereotypical superlative.

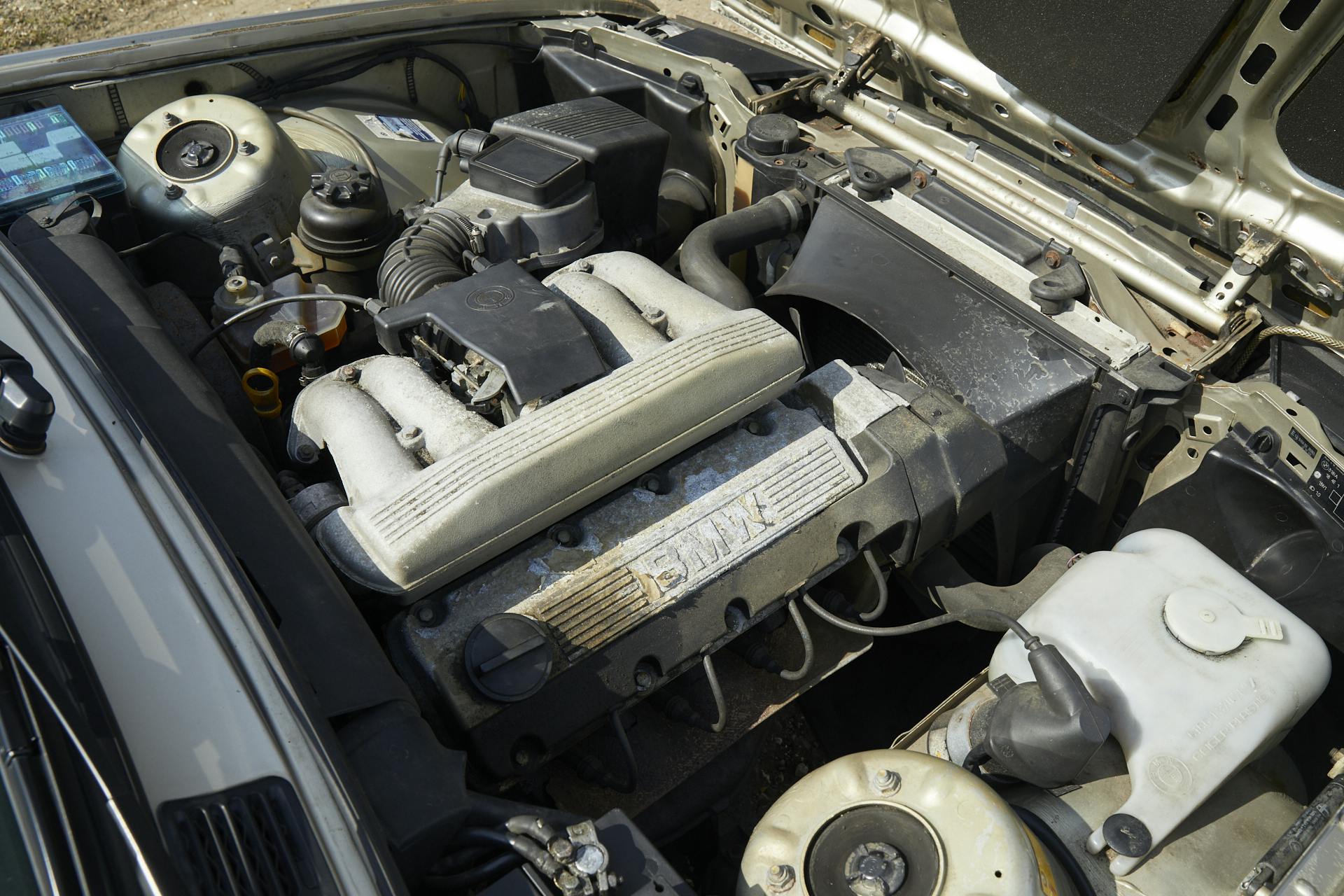

The BMW isn’t much worse for wear, on similar miles in this case—around 72,000—and stickered as ever to one of the strut towers under the bonnet is the name of its sparkling hue, Bronzitbeig Metallic. It’s the only two-door here, rides on period-correct 14-inch “bottlecap” alloy wheels, and is otherwise unadorned; the previous keeper even removed its 318i badge from the trunklid.

One reason for its survival isn’t just that nine-year owner Martin Ryles has treated it like a member of the family, but also that the raised center console houses the telltale T-handle of BMW’s 1980s automatic gear selector. This is apparently kryptonite to those who’d drift around neighborhood roundabouts every Saturday night, “slam” it on eBay springs, or tastelessly black-out its kidney grilles and window surrounds. The result is a car maintained in its pure and original form.

Pure and original, but not perfect—Ryles points out a few rust spots and dings, and uneven pattern panels from prior rust repairs, evidence the car isn’t a garage queen. The interior though is basically unmarked. With brown velour trim and doorcards like big chocolate bars it’s so Eighties I could almost feel the red braces starting to curl over my shoulders. While its owner remarks on an offset driving position, the space regained from only having two pedals means ankles remain untwisted. You sink lower into the seats than in the others, and no current BMW designer should be allowed anywhere near a computer without first studying the clarity of those dials or slimness of its steering wheel.

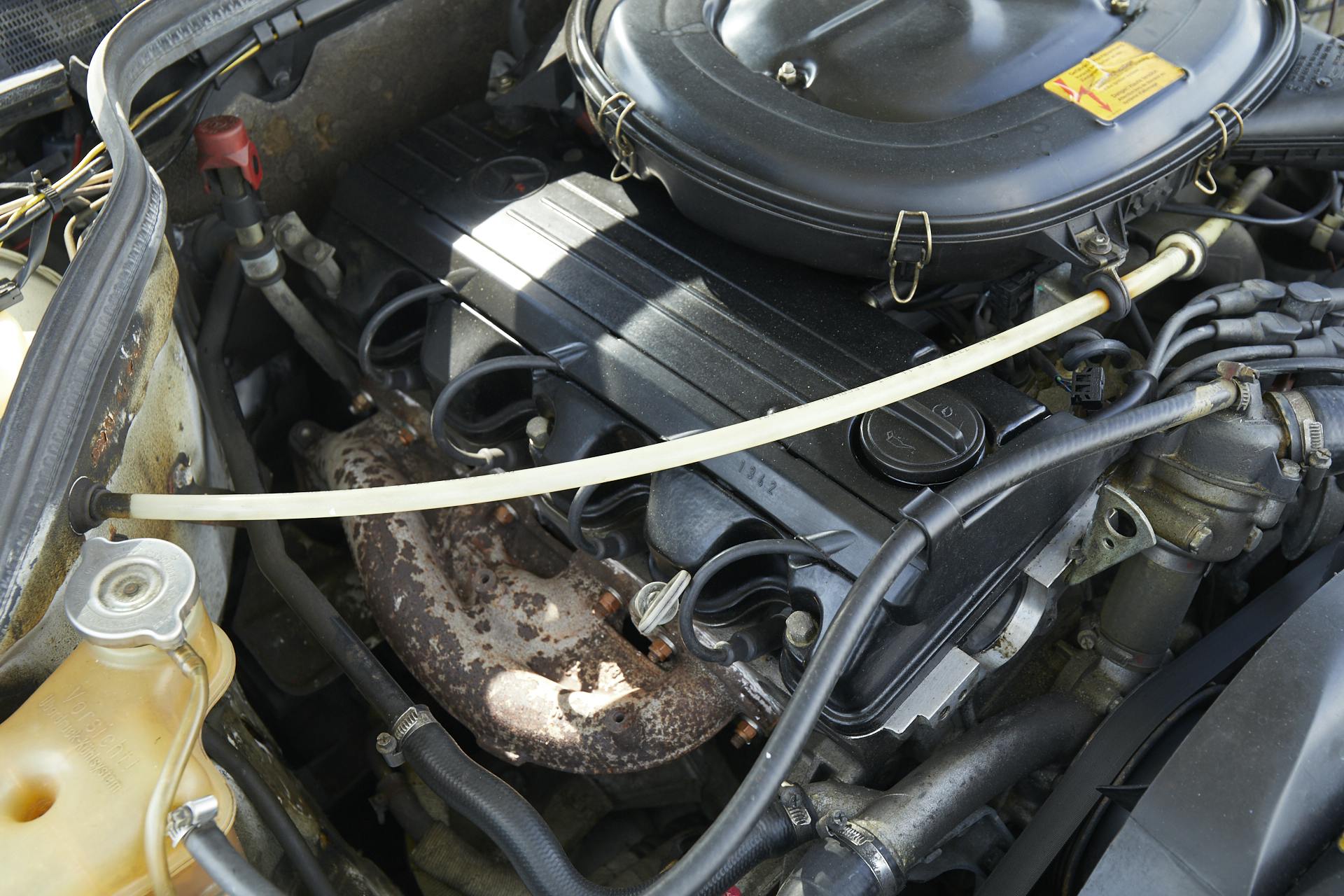

If there’s clarity in the BMW’s instruments it’s to be found virtually everywhere in the 190E. Its four-door shape lacks the modernity of the Audi or the BMW’s taut form, but Bruno Sacco got its near-perfect proportions and absence of superfluous details right on the first go. Mercedes got the engineering right too, from its standard-setting multilink rear suspension right down to the smallest details, like the way its four jacking points are capped by hardy rubber bungs to stop you curling up the sills.

190E owner Oliver Hagger can’t be with us today so Hagerty UK editor James Mills arrives in the car instead. As close to perfect as you’re likely to find (the 190E, not Mills), with barely a third the mileage of the others (still talking about the Merc), there are no obvious flaws in the crisp white paintwork or charmingly basic unpainted bumpers. Mercedes wasn’t overly generous with equipment back in the day, perhaps a way of recouping profit from cars engineered with a money-no-object approach. Evidence of this: Mills and Ryles both raise an eyebrow when I’m unable to find the switch to raise the driver’s side window. There’s not an app for that, but there is a hand crank.

The door unlatches with a precision click and shuts with a mechanical thunk that betrays modern soft-close doors as mere gimmickry. The seats are sprung like a Victorian mattress and apparently haven’t been kind to the editor’s back on the journey up. I’ve fallen hopelessly for the graph-paper fabric though and don’t even mind the use of I Can’t Believe It’s Not Burr around the snaking gear selector and Eighties-obligatory cassette holders.

It’s funny how some details have persisted. Mercedes had already adopted its combined lights ‘n’ wipers stalk by this point, though it’s on the right here like old British and Japanese cars and liable to initially confuse anyone used to anything else. The ignition slot, meanwhile, is on the left, also where you don’t expect it. The steering wheel is big enough to steer the Ever Given out of trouble, while the instruments nearly match those of the Audi and BMW for clarity but exceed them for quantity; you get six needles plus an inset clock, to the BMW’s five and the Audi’s four.

Driven to succeed

Since the Audi was dropped off at my doorstep, I get familiar with it before even stepping foot in the others. It’s a mark of either the car’s forward-thinking design or the Volkswagen Group’s fastidious policy of evolutionary improvements that you could pluck someone from a modern, manual-‘box A4 (or indeed a Golf, or an Octavia, or virtually anything else) into the 80 and it’d still feel familiar to them.

The only “huh…” moment comes when I attempt to find the headlight switch, which has been a rotary control by the doorcard for decades but in the 80 is a small, separate stalk in front of the indicators. The well-defined but slightly obstructive gearshift evokes the group’s modern offerings too, even if the engine it’s attached to dates things more. From the moment it fires up (quickly and cleanly like all the injected cars here) it sends a resonance through the whole car and on the move needs stoking beyond around 3000 rpm before it begins to feel all of its 2.0-liter capacity.

The sportiness though I wasn’t expecting. Hang onto the revs and an induction snort permeates through the dashboard, and the 80 then parps enthusiastically to its 6400-ish-rpm red line. BMW owner Ryles even reports evidence of what an Audi press release would today call an “emotional” exhaust note, audible every time I exit a junction. This activity results in the steering wheel fidgeting this way and that, a reminder that even front-wheel drive cars with modest outputs used to torque steer, and the 80’s relatively unsophisticated rear beam axle occasionally serves as a further reminder, over harsher bumps, why independent suspension is now considered preferable.

The Mercedes quickly justifies both its multilink rear and the extra money it cost when new. To pick a neutral year when all three were on sale, 1990, an Audi 80E 2.0 came in at £13,375, a BMW 318i two-door (with a manual) £100 less than that, but the 190E 2.0, again with a manual, a full £18,000. Crikey. To spend the same on the Audi or BMW you’d have needed a five-cylinder Audi 90 or the six-cylinder 325i. In 2021 money, it works out around £42,000 ($58,300).

But again, easy for the Mercedes to justify. The cabin we’ve covered, but the 190E also starts and idles smoother than the Audi and while there’s no manual gearshift to play with, the Merc’s automatic selector has the mechanical and audible tactility of the levers in a signal box rather than a transmission. The floor-hinged accelerator pedal needs a bit of a prod to elicit motion but the torque converter takes up drive as smoothly as an electric motor.

Progress is … stately. The 2.0-liter isn’t keen to rush things and there’s a good “are you sure?” pause before the gearbox kicks down when you ask for more. While the captain’s wheel is light in small motions it weights up as you heave-ho through even fairly gentle turns, but the ride is like being on a millpond. The nautical references continue with the crow’s nest driving position over a low belt line, but appropriately it gives you a sense of command over your vessel—guided, naturally, by that gunsight on top of the radiator grille.

The BMW doesn’t instantly feel more enthusiastic, but it does grow on you. The whole driving environment is more focused of course, despite the brown’s best efforts to put you into a cruising frame of mind. The auto gate isn’t as well defined as that of the 190—finding the right direction is a case of looking, rather than feeling—but the BMW still steps off the mark more smartly than the Mercedes.

From there its dearth in capacity begins to show, the 190E inching ahead on each straight, the sportier Audi with its driver stirring their own gears long gone. A manual would no doubt even the balance, but the relaxed progress does allow you to appreciate the syrupy flow to the 318i’s ride and the similarly light touch to the steering. While slower, there’s more of a sense of mechanical things happening beneath you in the BMW too, compared to the Mercedes at least; gearchanges are a little snappier and the throttle response sharper.

Where the natural order of things gets muddled is when you tackle more sinuous roads. Here the BMW dominates, the Mercedes rolls, and the Audi understeers, right?

Not quite. The Audi, on its balloon-like sidewalls, seems to hunker down and get stuck in. The steering is quicker than the others and the extra agency over its gearbox means you drive it like a big hot hatch. Not a particularly sharp hot hatch, it has to be said—maybe the slightly flabby Mk3 Golf GTI that shared its eight-valve engine—but with the raspiest soundtrack and most confidence-inspiring handling you end up driving it more like a modern car.

After a brief go in the 318i, editor Mills is smitten with the BMW way of thinking, but for me the Mercedes’ chassis is more of a surprise. That initial limo-like slop seems to bleed away when you up the pace. It’s a more confident (and confidence-inspiring) car as the roll stabilizes and the chassis wakes up.

Perhaps it’s that clever rear axle, or the steering going from sailboat to speedboat when you lean harder on the front end. It’s better still if you knock the gear selector down a ratio or two to bring some balance to proceedings. Even the brakes feel good, with reassuring weight behind the pedal and plenty of bite. The car’s demeanor doesn’t exactly encourage it—you could go a lifetime happily wafting about using a tenth of its abilities—but it’s no surprise the Cosworth-engined models have a following as the 190E was clearly engineered for much more.

The BMW’s relaxed steering ratio and less sophisticated trailing-arm rear actually endow it with the least incisive feel of the bunch, despite the reputation of the badge on the bonnet and its own more potent siblings. No doubt it’d feel fizzier with a manual ‘box and the contemporary M Technic bits (or as the more powerful 318is of the era, which BMW pitched as a Golf GTI rival), but this one’s resolutely a cruiser, not imparting quite as much information back to its driver.

Surprised? A little, but there are some things it undoubtedly does better than the others, signs of that BMW attention to detail filtering through. It corners flatter than the Mercedes but without the Audi’s beam axle thump, the steering weights up more naturally than either, and the driving position is the easiest to get used to, despite the slight twist. You really do feel perched in the Mercedes, while the Audi’s low-slung feel is compromised by a high-set throttle pedal that needs a second ankle mid-shin to operate comfortably.

The BMW still gets along with modern traffic and its four-speed auto trades sprint gearing for longer-distance schleps—which, really, is what it was designed for. Trading up from a Sierra or a Cavalier it probably felt like a go-kart, but today, like the Mercedes, it’s at its best at a gentler pace, and demonstrates that BMW’s remit went far beyond homologated DTM cars.

Premium contentment

This isn’t a test with winners or losers, but I do feel compelled to point out a few things. Having spent the most time in the Audi, it was the relaxed and wonderfully preserved Mercedes that I found most charming. BMW owner Ryles too went away wondering if he should swap his 3 Series for a 190E, while Mills, who had the most seat-time in the Merc, preferred the drive offered by the BMW. So the Audi comes last then? Not really; as presented, it’s the most capable on both the straights and the corners, the only one to make B-roads a destination rather than a means of connecting the dots, and feels most suited to all-weather, round-the-clock use.

It is also the most affordable of the trio. Hagerty insured it for around £3000 ($4200) for our test, the BMW for about £5000 ($7000) and the (admittedly low mileage and absolutely immaculate) Mercedes for £8500 ($11,800). On the open market, you’ll still find the Audi cheapest to buy, followed by most examples of the Mercedes, while the desirable manual E30s that haven’t been driven to destruction are now knocking on the door of five figures. Performance variants (S2, Cosworth, M3) are in a different league entirely, though notably the 3 Series is most expensive in that arena too. (Note: All values reflect the current U.K. market. For up-to-date U.S. values, click here)

And in a modern context, all three remain genuinely usable. Ryles drove from North Yorkshire down to Bedfordshire and back in a day in the BMW, the Mercedes did a round trip from Kent, and the Audi felt good … well, for a day trip to the Black Forest, frankly, with some flat-out Autobahn thrown in for good measure.

As alluded to further up, the real talking point here is that these cars of similar size, market position and purpose are just so different both to own and to drive. Contemporary buyers could choose each on distinct merits that spoke to them, rather than on the strength of badge alone.

That distinction would have applied equally had we introduced any other vehicle you might have considered a rival at the time too, from the Alfa Romeo 75 to Saab’s 900. If we pulled together their modern equivalents, I’m not sure you could say the same.