Media | Articles

22CV: Citroën’s V-8-powered Traction Avant remains a riddle 87 years later

For decades, Citroën’s mechanical ambitions were totally at odds with its budget. And it would be fair to say that the brand’s range-topping sedans never received the engine they deserved. This “curse,” shall we say, stemmed from a car in the early 1930s—a prestigious, V-8-powered version of the innovative Traction Avant, called 22CV. The vehicle never saw the final light that awaits at the end of a production line. Nearly 90 years later, the super-Traction remains the only Citroën ever equipped with a V-8 engine, as well as one of the most mysterious models in the French company’s history.

High society’s Citroën

Released in April 1934, the Traction Avant (“front-wheel drive” in French) was celebrated as model of innovation. Its four-cylinder engine was mounted backwards, between the front wheels and the firewall, while its transmission was located at the very front of the car. The Traction Avant featured unibody construction, and it turned heads with relatively aerodynamic lines. It’s on these sturdy foundations that Citroën tried building what could have become its first true luxury car.

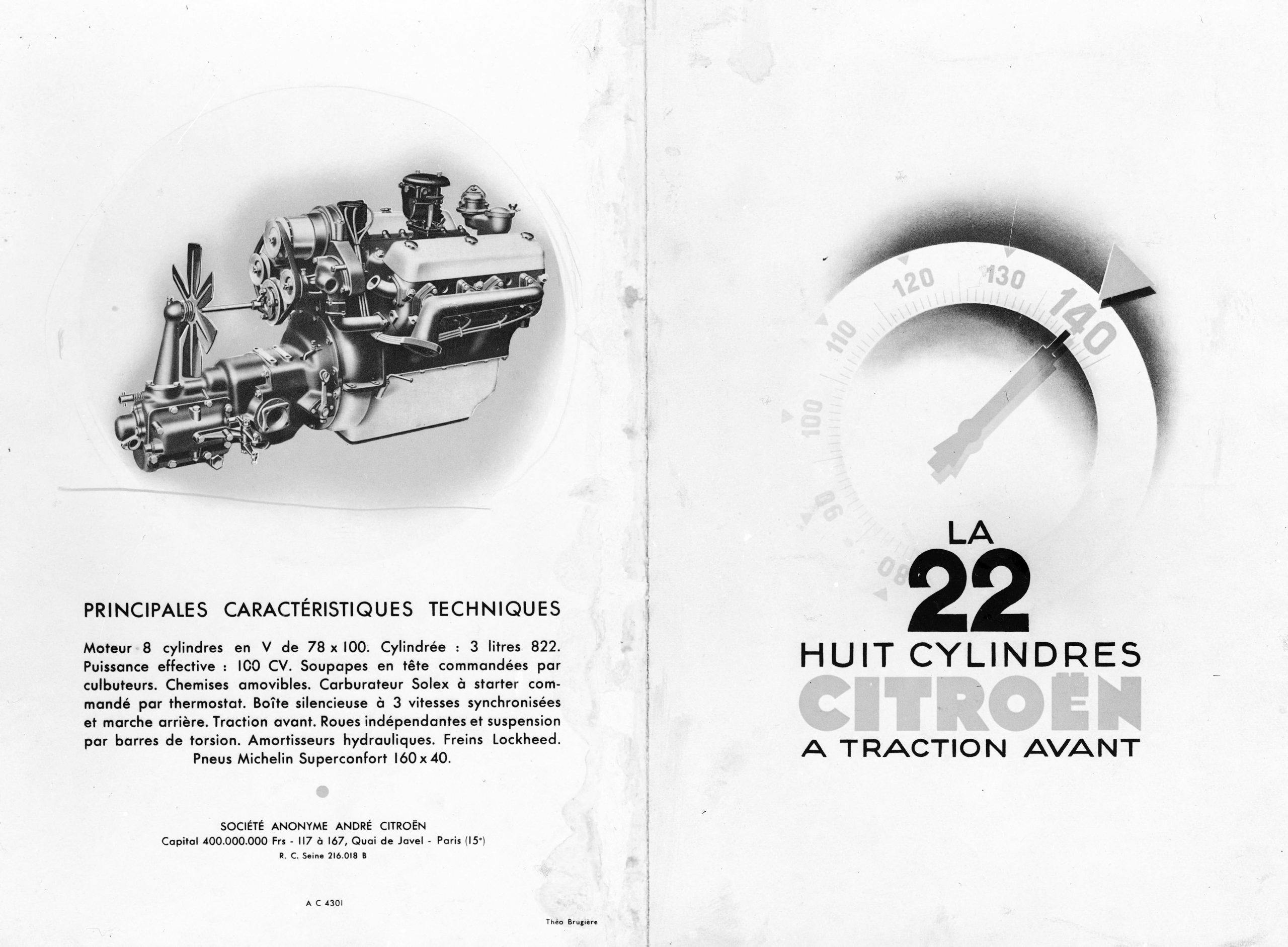

Engineers envisioned the 22CV as a flagship model, allowing Citroën plant a flag in a segment just above the mainstream ones in which it normally operated. In no world was this V-8 Traction Avant intended to keep Bugatti up at night. The name 22CV denoted the taxable horsepower rating, a common practice in France at the time that also accounts for the the 2CV’s name. Power came from a 3820-cc overhead-valve V-8 designed in-house and said to develop at least 100 horsepower. This engine was not in any way related to the 3650-cc flathead V-8 Ford launched in America in 1932.

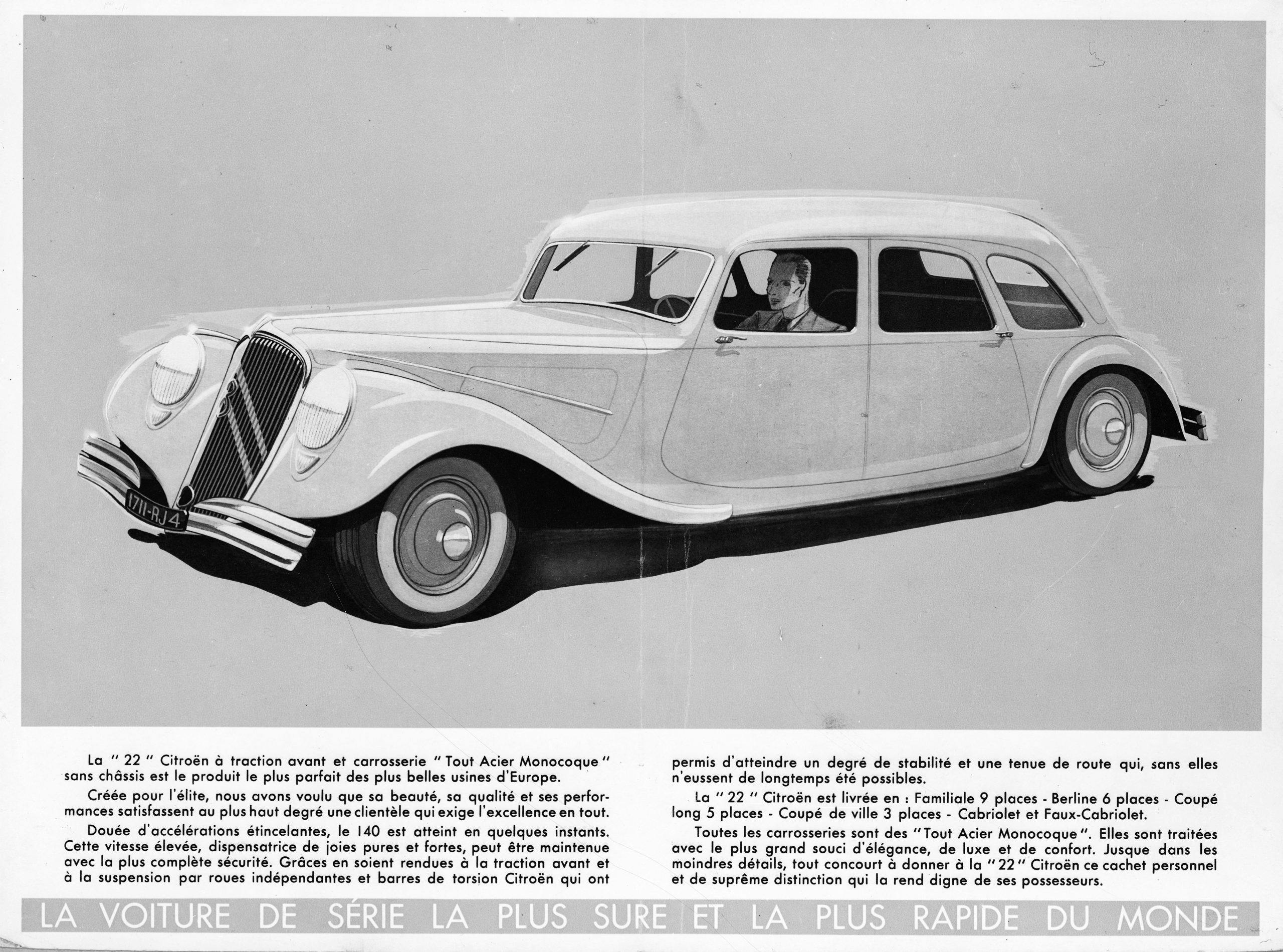

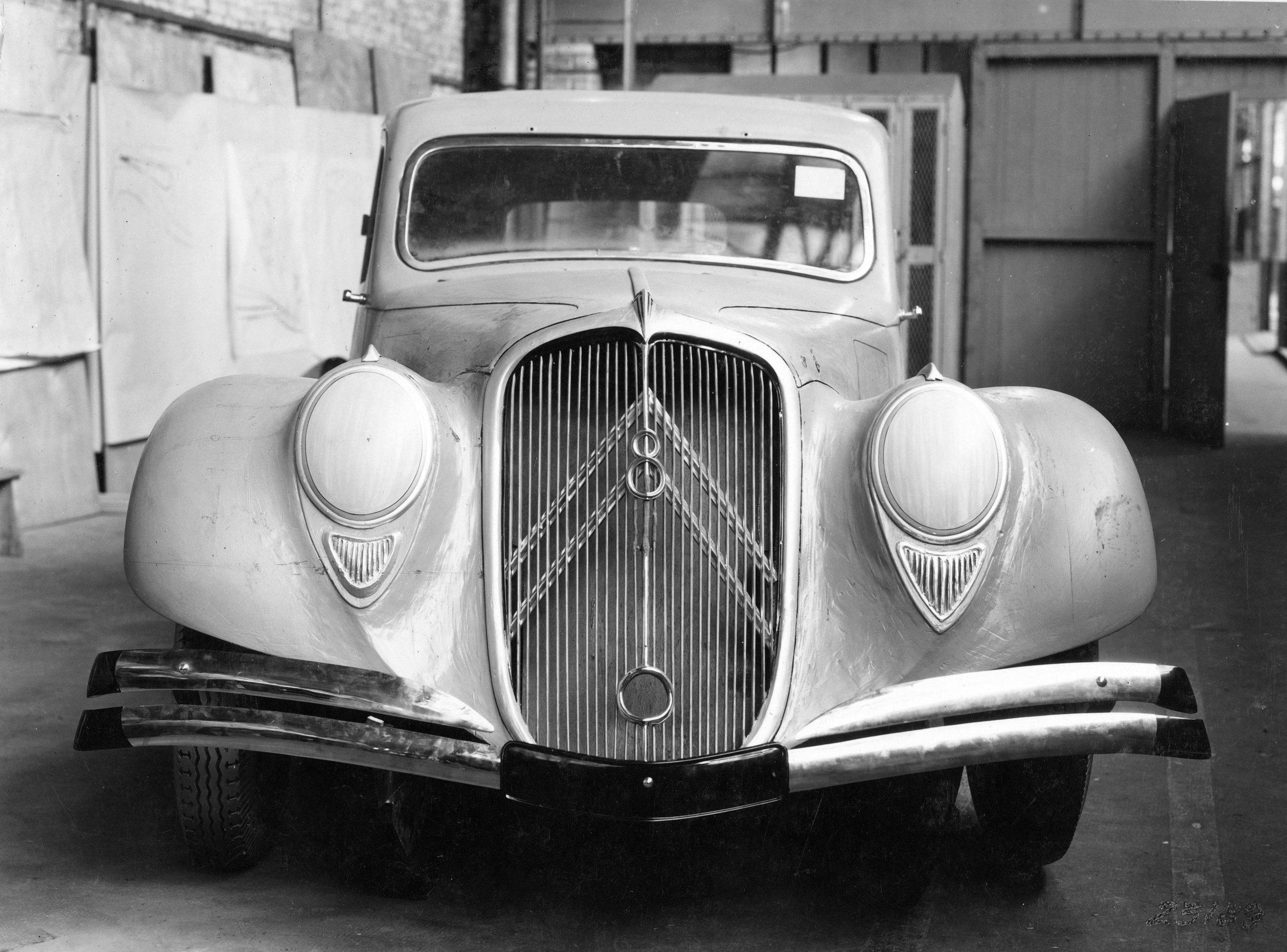

Early tests concluded that the V-8 gave the 22CV a top speed of about 87 mph (around 140 kph), a respectable figure in an era when speed was still a luxury, especially in Europe. Headlights integrated into the front fenders, and an 8-shaped emblem proudly displayed on the grille, were among the design cues that set the 22CV apart from variants with four (and, starting in 1938, six) cylinders, but interior modifications were largely limited to a model-specific speedometer and minor trim-related updates. Citroën intended to unveil the 22CV at the 1934 Paris auto show.

Creating a V-8 from scratch on a shoestring budget, with 1930s technology, was a daunting task. Most historians agree the first 22CV prototypes let loose on public roads were powered by Ford’s flat-head V-8, which might be the source of the rumor that the design was copied in Dearborn and pasted in Paris. This strategy allowed one team of testers to verify the structural reinforcements, as well as the suspension modifications made to the Traction Avant, by logging real-world miles while other testers fine-tuned the engine on a bench in preparation for a 1934 launch.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

On the face of it, Citroën kept its promise to unveil the 22CV in Paris in 1934. It displayed three cars at the Paris show, including a shapely roadster, and it presented its V-8 on a stand for show-goers to ogle. Some high-profile clients were even offered to take a fourth car for a quick spin through Paris. Mission accomplished, right?

Not exactly. Nearly nine decades later, historians still disagree about whether the cars displayed on the show floor were equipped with any engine at all, let alone the aforementioned V-8. One show car (the long-wheelbase model) was displayed with its twin hoods open, so there’s no doubt that a Citroën V-8 was in that engine bay, but the others were closed and locked. But what exactly did the lucky few given a go in the 22CV during the auto show drive? Was it Ford- or Citroën-powered? We still don’t know for sure.

One point that shouldn’t be understated: The 22CV was not merely an science fair-like gizmo cobbled together with whatever parts were available at the time. It was developed, built, and tested with mass production in mind. Citroën had even started printing marketing material, like sales brochures for its dealers. Citroën even took a handful of orders. Period literature (kindly sent to Hagerty by the carmaker’s archives department) sketched the outline of a car “created for the elite.” It was available as a sedan with six or nine seats and as a convertible, among other body styles.

Out of time and resources

Preparing the 22CV for production was more challenging than anyone anticipated, and time was not on Citroën’s side. Engineers ran into issues with the three-speed manual transmission, whose gearing wasn’t well suited to the V-8, and they simultaneously tried to solve the problems while experimenting with automatic and four-speed manual units. Some prototypes overheated, others burned oil, and reports of frightening structural problems were not uncommon.

The 22CV was beginning to look more like a jinxed cash arsonist than a prestigious flagship, and Citroën’s resources were perilously low. The company felt the full gut-punch of the 1929 stock market crash, yet company founder André Citroën (1878-1935) spent a small fortune on the Traction Avant program in the first half of the 1930s. He also overhauled his company’s Quai de Javel factory in Paris. His prediction that the standard, four-cylinder-powered car’s success would justify these investments turned out to be wide of the mark; early cars rushed to production were plagued with problems (including snapping driveshafts) that gave the car a vile reputation.

Faced with mounting debts, Citroën filed for bankruptcy in December 1934. Michelin stepped in to save the firm, preventing it from being nationalized, and ostensibly ousted André Citroën. One look at Citroën’s balance sheet set off a five-alarm panic in the board room. Strict cost-saving measures were announced, including slashing the carmaker’s advertising budget, closing factories, and selling non-essential sub-brands.

Slashing through 87 years of rumors

What happened next largely depends on which well of information you drop your bucket into.

One of many suppositions is that Michelin canned the 22CV project and ordered Citroën to destroy anything related to it, such as parts, documents, and machinery. Another is that Michelin cleaved the budget allocated to the project but allowed it to continue after the take-over. And, some suspect the lessons learned from the 22CV were funneled into the 15-Six that was released in 1938 with a straight-six engine. Regardless, the plug was pulled in the 1930s.

Don’t look for a 22CV in the Citroën collection or at a ritzy car show; none remain. One of the more credible and less contentious claims gravitating around the car is that the 20-or-so prototypes built were rounded up and brought back to the factory, where they were converted into 11 Normale models and—in line with the “profits first” strategy—sold to unsuspecting buyers. However, another hypothesis is that some of the prototypes somehow didn’t get caught in the strainer and went on to live a reasonably normal life. It’s a little far-fetched, and there isn’t sufficient evidence to back up up any one storyline, but keep in mind that Citroën allegedly destroyed all of the M35s, every GS Birotor, and the full batch of pre-series 2CV.

If a 22CV miraculously survived, it hasn’t been discovered, and none of the 22CV sightings reported have been verified. One of the most intriguing morsels of hearsay came from a Citroën dealership in Chartres, France, which handled parts requests from colonies and overseas territories. In 1948, it allegedly received a telegram from Vietnam asking for the parts needed to rebuild a 22CV water pump. The store replied that the parts were not available. That was that. Was the water pump rebuilt using parts the mechanic had laying around, or was the 22CV parked in a Vietnamese courtyard and forgotten about? Is the story even true? Only a long expedition to Vietnam could provide answers. But, if a 22CV prototype was genuinely dispatched to Vietnam, what are the odds that it survived brutal years of war? Likely not good.

In the meantime, the last vestige of the ill-fated 22CV is a weathered headlight bezel discovered in a repair shop in Lyon in 1966. Framed, it was auctioned for 5580 euros (around $6900 at the current conversion rate) in 2019.