Media | Articles

A brief history of missing clutch pedals and almost-automatics

Since the dawn of the automobile, automakers have sought to make driving easier and more approachable. Oftentimes that has meant engineering ways around our beloved clutch pedal and gear lever. Early motorized vehicles were a jumble of confusing sliders, levers, buttons, and dials that would confuse any modern driver. The quest to simplify these controls took several twists and turns, achieving varying degrees of success.

The first commercial version of what we would today recognize as a true automatic transmission didn’t appear on the market until 1939, when Oldsmobile debuted the fluid-driven Hydra-Matic. In doing so, General Motors made driving much more accessible to legions of newcomers. Both before, during, and after that period, however, car companies continued to chase down the quixotic dream of shifting a manual gearbox without having to use the clutch.

These sometimes roundabout solutions were born from various origins. Some designs devised a path around the pre-torque-converter reality of daily driving, while others attempted to further sharpen the sports car experience without taking any control away from the driver. Then, naturally, came efforts that were simply a boon to anyone too lazy to engage their left foot while out and about.

Pre-select for driving pleasure

Manual transmissions got infinitely easier to use following the invention of synchronizers, or synchros, which operate much like an internal clutch to match the speed of the input and output shaft of a transmission and perfectly align gear teeth before they are selected. This obviates the tedious double-clutch footwork required to put the transmission in neutral in between moving from one ratio to the next in a fully-meshed gearbox, while also cutting down on gear grind.

Before synchromesh became commonplace, transmission designers tried all manner of methods to avoid putting drivers through the footwell two-step. Of these, one of the most fascinating and successful was the preselector, which appeared first in the 1930s and lasted well into the 1960s (with military vehicles being the last to eschew them). A preselector system allows a driver to choose which gear they think they will need far in advance of it actually being grabbed by the transmission itself. The gear was usually preselected using a button or lever mounted on the dashboard, with the gear change itself only occurring once the driver pushed a floor-mounted pedal.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

How did this innovation work, exactly? Although there were various preselector designs in use, the most common models used permanently meshed epicyclic gears that relied on an internal braking system to distribute torque from one forward ratio to the next. The popular Wilson model, for example, strung together each successive gear to modulate the amount of reduction they provided, with the top gear (usually fourth) locking all previous cogs together and operating as a single continuous unit at a 1:1 ratio. The kick pedal on the floor was used to lower a bus bar that engaged the gear.

Although there were similarities between later automatic and early preselector transmissions, the latter was still firmly manual in terms of its operation. Drivers had to choose their next gear each and every time and could even select a gear and never use it by simply not engaging the change pedal. There was no need row gears sequentially; all gears were available at all times, which meant one had to be cognizant of the lack of reverse-gear lockout.

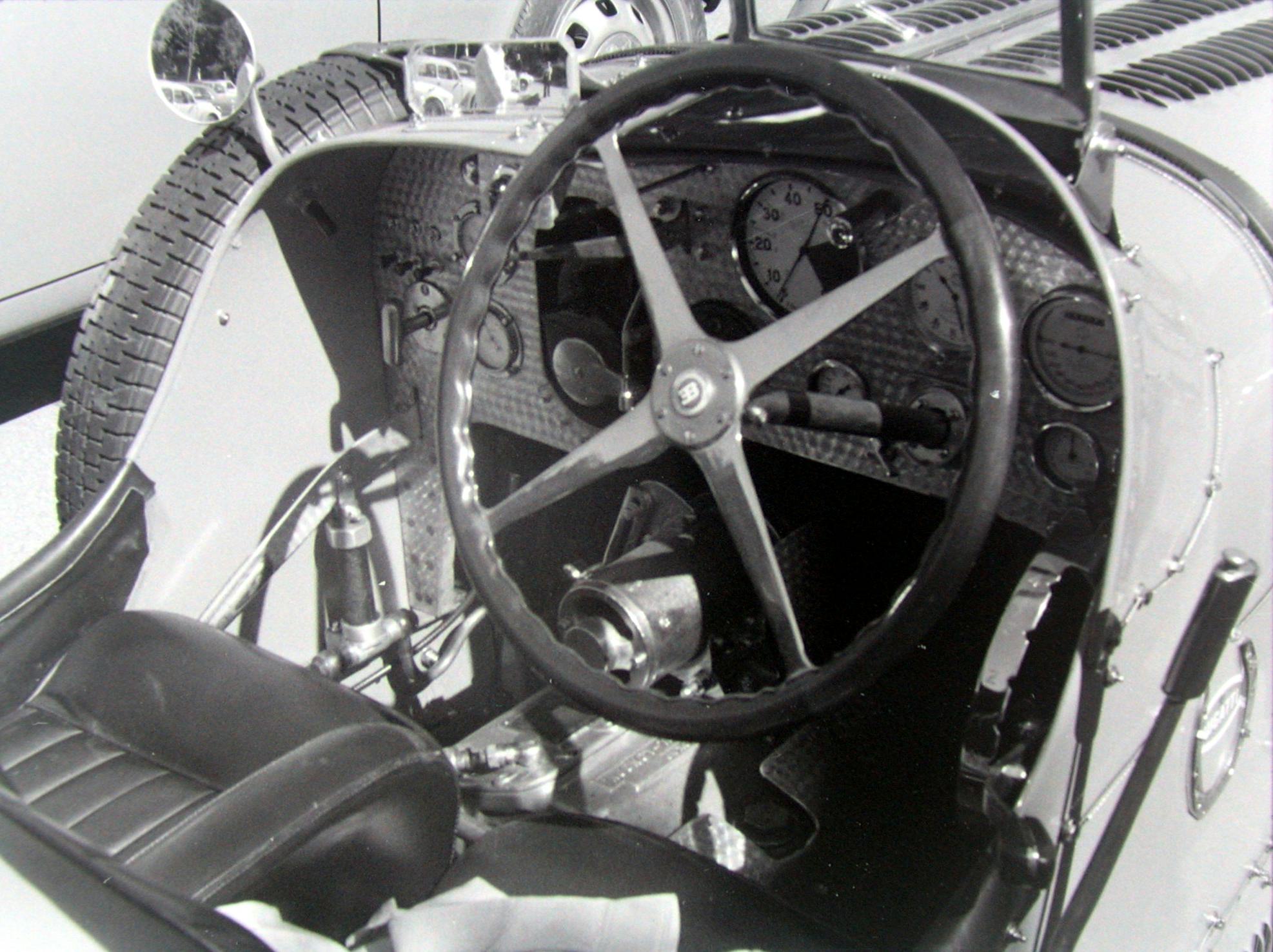

Not all examples of the preselector, however, did entirely without a clutch pedal. While some cars, such as those built by Daimler or BAS, used a fluid-type flywheel to handle engine output with the handbrake or footbrake holding the car at a stop, other cars relied on a centrifugal clutch (similar to what’s found on a riding lawnmower) or even a manual clutch that added yet another pedal to the floor. Race cars, which quickly adopted preselector technology, used no clutch at all, as an abrupt start made no difference to open-wheel drivers who appreciated the ability to choose their next post-corner gear from the relative serenity of the preceding straightaway.

Almost automatic, except where it counted

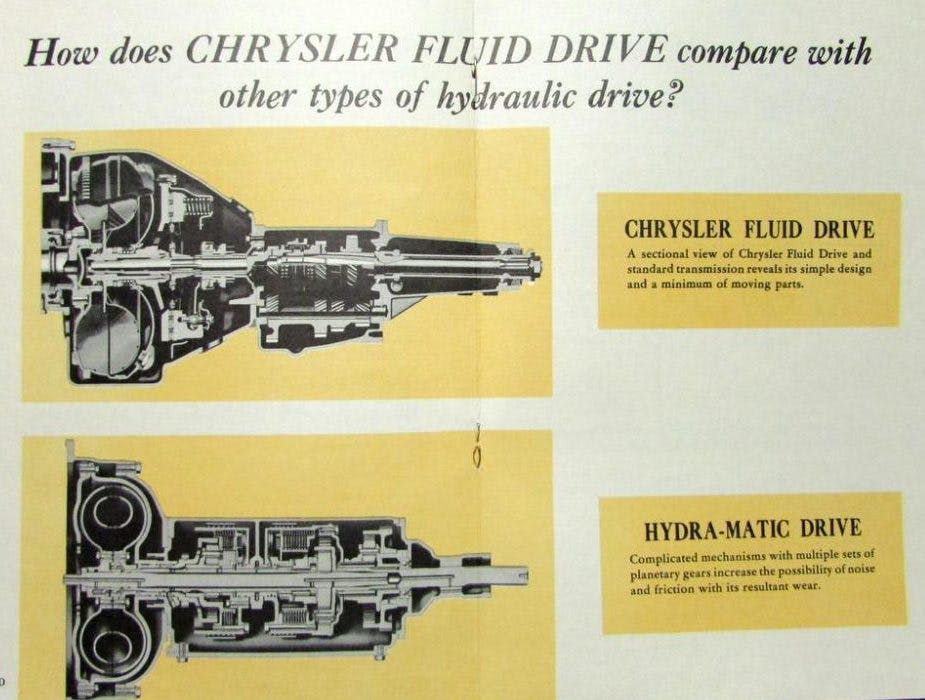

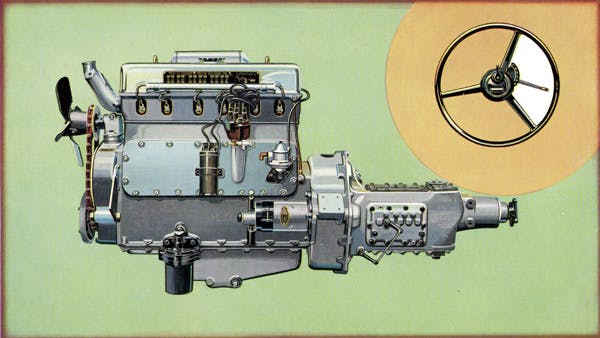

Chrysler took a swing at a clutchless manual gearbox starting in the late 1930s, with production continuing well into the ’50s. Labeled “Fluid Drive,” or “HyDrive,” depending on which sub-brand in which it was installed, the system employed a conventional three-speed manual gearbox but swapped out the flywheel for a fluid coupling similar to that of a modern torque converter, only without torque-multiplication capability.

This precursor to the modern automatic still required a clutch pedal to move from one gear to the next, but outside of that it was seldom, if ever needed. It was possible to hold a Fluid Drive car stationary while in gear without using the clutch at all, and hill starts could be accomplished by simply transitioning from the brake to the accelerator. Chrysler recommended leaving the car in second gear at lower speeds, but it could pull away from a stop in any of its three gears thanks to the fluid coupling’s power transfer.

An even less involved version of the transmission, the M6 Presto-Matic, was also available from Chrysler. While it required the use of a clutch to initially select offering the choice between High and Low settings, once away in normal driving the clutch never again entered the picture. The transmission was then capable of shifting itself in and out of two gear sets within the scope of the original selection (High/High Overdrive, Low/Low Overdrive), after lifting the throttle at speeds roughly above 15 mph (upshift) or below 11 mph (downshift), with slight variations depending on whether you started out in Low or High.

If that sounds clunky, you’re not wrong. Sometimes called Gyro-Matic, or Tip-Toe Shift, the setup was far from a true automatic in terms of smoothness or power delivery, and it didn’t deliver the same degree of control as a traditional manual. Still, it was reliable, and it served Mopar fans from 1946–53 before true autoboxes became commonplace.

Sensonic, but not sensible

Our final entry into the clutch-free manual pantheon hails from Sweden. In the early 1990s, Saab decided that there existed a customer who was engaged enough to want a manual transmission in their car, but not quite willing to go through the effort of actually using a clutch pedal to make the magic happen. Enter “Sensonic,” perhaps the most unusual attempt in modern memory to remove a clutch from the manual-transmission equation.

What’s important to understand about Sensonic is that it had nothing in common with existing sequential manuals or the automated single and dual-clutch transmissions that followed. It was, for all intents and purposes, a traditional manual gearbox just like any other five-speed you could buy in the Swedish brand’s portfolio. The only difference was that instead of relying on the driver’s left foot, Sensonic activated the clutch completely electronically, with no intervention from the pilot whatsoever.

Designed by automotive supplier Fichtel & Sachs (later absorbed by what is today ZF), the system composed sensors that detected the movement of the shift lever as well as the amount of pressure being applied to the accelerator. It was programmed to electronically activate the clutch within very specific parameters, based on the motion of the shifter. Flooring the gas locked out gear selection, but if you backed off the go-pedal the vehicle’s clutch electronically activated to facilitate the change.

Sensonic was inexpensive for Saab to implement but weird to use in practice and not exactly reliable over an extended period of time. Available exclusively in turbocharged versions of the 900, very few buyers ticked the Sensonic box between 1993 and 1998. In hindsight that’s not surprising; who exactly was the target market for a laissez-fair manual that wouldn’t simply prefer a full-service automatic? Fichtel & Sachs partnered with a few boutique automakers, such as RUF, while developing the technology, but outside of a handful of sports cars it was an outlier.

Tech takes over

Today, the dual-clutch automated manual is the dominant player in the alternative automatic-transmission game, as demonstrated most successfully by Volkswagen Group in everything from the Porsche 911’s PDK to the GTI’s DSG. Such gearboxes are capable of lightning-quick shifts and are designed for less power slip than with a torque converter, thereby increasing fuel efficiency.

The dual-clutch is an elegant solution to what was once, many years ago, a pressing problem for marketers seeking to get everyday folks off the sidewalk and into the driver’s seat. The complex machinery and engineering advancements that go into each of these gearboxes would have been unimaginable a century ago. If anything, the path from pre-select to dual-clutch demonstrates all of the wild avenues that needed to be explored in the search for a better-shifting transmission.

With all that said, modern traditional torque-converter automatics are more efficient, more refined, and more reliable than ever before. Even in high-performance applications, traditional automatics with eight and ten speeds are becoming more and more prevalent. Anyone who’s driven the quick-shifting 10-speed from the Camaro ZL1 and Shelby GT500 would be hard-pressed to find any slush in that so-called slushbox.