Media | Articles

The Nash-Healey was a car ahead of its time

Some things are undoubtedly ahead of their time. When it comes to consumer products like automobiles, that usually means commercial failure, even if the general concept was sound, as proven by success when applied later.

Let’s look at a few concepts that proved to be sound. Carroll Shelby took the idea of putting American power in a British sports car and came up with the Cobra, continuation models of which are still being produced as you read this. Speaking of sports cars, the Corvette, a two-seater introduced by an American automaker in 1953, is also still in production today. Zora Duntov took that first C1 Corvette, a boulevard cruiser, turned it into a true sports car, and then it was taken to Le Mans with success.

Those were good ideas, and they were all implemented before the Cobra and Corvette by Donald Healey and George Mason with the 1951–54 Nash Healey. Some consider it the first American sports car, though Anglo-American would be more accurate.

Most people know about Donald Healey because his surname was appended to sports cars he developed, which were marketed by Austin and Jensen, but Healey had a long, successful, and varied career in the automotive world long before the first Austin Healey was made.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

He was born in 1898, which made him 16 years old at the start of World War I, when he volunteered for the Royal Flying Corps, having served as an apprentice at the Sopwith Aviation Company while studying engineering. Healey flew combat missions and survived a number of crashes, including being shot down by friendly fire. After the war he studied automotive engineering via a correspondence course, allowing him to open up a garage and car rental shop. That led to an interest in motorsports and rallying. Healey proved to be at least as good behind the wheel as he was with a wrench, competing in nine consecutive Monte Carlo rallies with an overall victory in 1931.

The following year he was hired by the Riley car company (later part of BMC and British Leyland), and he then moved to Triumph as head of experimental engineering in 1933, eventually becoming technical director. He must have been talented, because he was soon recruited by Joseph Lucas Ltd. in 1937, Triumph lured him back with a seat on the board of directors, quickly appointing him managing director.

That turned out to not be much of a reward. In 1939, Triumph went into receivership and the company that bought the assets closed one of the firm’s two factories and leased the other, so Healey was out of a job. He found work at Humber, a Rootes subsidiary, working on armored cars during World War II.

Despite the fact that much of Triumph’s tooling in Coventry had been destroyed by German bombs, Healey and some of his coworkers at Humber—stylist Benjamin Bowden, whose swoopy Spacelander bicycle was a flop in the 1950s but is highly collectible today, and engineer A.C. “Sammy” Sampietro, who later served as chief engineer at Willys Jeep—starting planning a clean-sheet Triumph that they hoped to build after the war. Unfortunately, when the trio approached the owners of the Triumph brand, they were rebuffed, perhaps because of a deal already being negotiated with the Standard Motor Company, the maker of postwar Triumphs like the TR-4 and Spitfire.

The fact that Triumph’s tooling had been destroyed turned out to be fortuitous for Healey and his compatriots, as their all-new design owed nothing to intellectual property belonging to the Triumph brand. Raising financing from friends and family, Healey negotiated a deal with Riley Motors for drivetrains and other components that couldn’t be made in-house, and in 1945 he started Donald Healey Motor Company Ltd. A roadster and a sedan went into production the following year.

The cars were low-slung and sleek, with lightweight aluminum skins stretched over wood frames mounted to a steel frame, and a trailing arm independent front suspension designed by Sampietro. At only 2500 pounds, with the 104-horsepower Riley inline-four, they could easily exceed 100 mph and were among the fastest cars available in postwar Britain. Healey cars won class victories in the ’48 Targo Florio and ’49 Mille Miglia. They were also rather costly, with the roadster running about $6300—the equivalent of about $68,000 today—so fewer than 400 complete cars and rolling chassis were sold.

The next Healey was a true sports car named after England’s most famous race track, Silverstone. Again using a drivetrain sourced from Riley, the chassis was redesigned to put the engine farther back for better weight distribution and the wood framing was dropped from the body, lowering weight. The lever action dampers on the earlier Healeys were replaced with modern telescoping shocks, with coil springs all around. Sampietro’s front suspension, a live rear axle (controlled by a torque tube), radius arms, and a Panhard rod made it corner. The body was racy, with cycle fenders, a windshield that folded, and cut-down doors.

One of the first American buyers of the Silverstone was Briggs Cunningham, who promptly pulled the Riley four, replacing it with Cadillac’s brand new overhead-valve, high-compression V-8, and swapping out the weaker Riley gearbox with something out of an American Ford. After learning of the engine swap, Healey and his son, Geoff, an engineer, managed to procure a similar engine. Testing revealed that while it weighed no more than the ancient Riley four-cylinder, it had 56 more horsepower, twice as much torque, and even helped with weight distribution.

Not only did an American engine make Healey’s cars perform much better, he understood that the U.S. market was vital to his company’s success. America was experiencing a postwar economic boom while Europe was still rebuilding from the war. Also, Donald Healey Motor Company was nearly £50,000 in debt and needed the business. Perhaps an American drivetrain that could be serviced by American dealers would make Healey’s cars more attractive on the other side of the pond.

Healey scheduled a meeting in Detroit with Ed Cole, chief engineer at Cadillac, and boarded the Queen Elizabeth, bound for New York. While crossing the Atlantic, Healey noticed a very fat man using a 3D camera on deck. The late 1940s saw stereo photography gain popularity with the introduction of the Stereo Realist 35mm 3D camera and related slide viewers. Healey was a photography buff and approached the gentlemen to ask about the camera. It turned out that both men ran car companies. The rotund photographer was George W. Mason, president of Nash-Kelvinator, and he invited Healey to join him at dinner.

Healey told Mason of his scheduled meeting with Cole and his plan to buy Cadillac V-8s for his next project. Mason wasn’t optimistic, telling Healey that it was likely a courtesy meeting and that Cadillac needed every engine it could build for its own car production. He did think the concept was sound, however, and told the Brit that if things didn’t work out in the Motor City, he should visit him in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where Nash was headquartered.

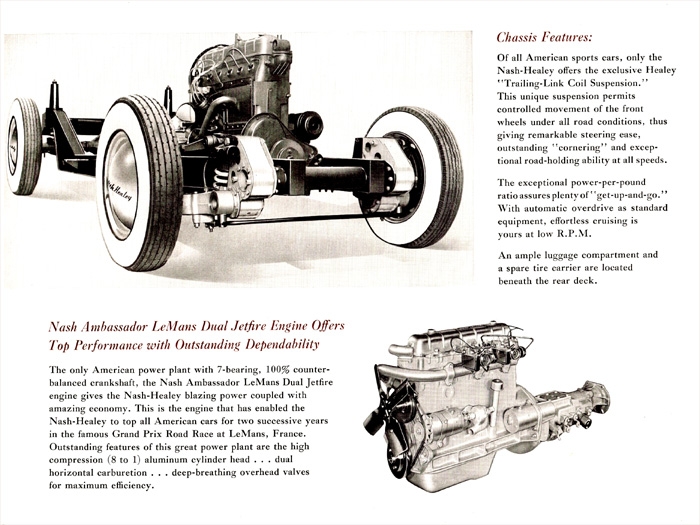

That’s exactly what happened. While Healey must have been disappointed about not being able to source the 160-horsepower Cadillac V-8, he went back to England with a deal that was probably better than he could have struck with General Motors. As with many of the independent automakers in the immediate postwar era, Nash hadn’t yet developed its own modern V-8 engine. It did, however, have a 235-cubic-inch straight-six that put out 115 hp, still more than the Riley motor.

Mason agreed to supply not just engines, but transmissions, overdrives, and rear axles—and ended up supplying headlights, bumpers, hubcaps, and torque tube as well. Even better, Nash would distribute the new sports car in North America through its own dealer network.

One possible drawback was that the Nash six weighed more than the Riley four, but it was reliable, very torquey, and—perhaps most important to a man whose company was in the red—available on very favorable credit terms.

The weight of the engine was reduced with a high-compression aluminum cylinder head that was fed with dual SU carburetors. A more aggressive camshaft completed the modifications, which yielded an increase of power to 125 hp, about 20 percent more than the Riley mill, with 210 lb-ft of torque. Bendix brakes from the much heavier Nash Ambassador were specified to provide adequate stopping power.

Healey entered the prototype in the 1950 race at Le Mans, finishing third in class, fourth overall, behind two Talbot-Lagos and Sydney Allard’s Cadillac-powered J2 but ahead of Aston Martins, Jaguars, and Cunningham’s own Cadillac-powered specials.

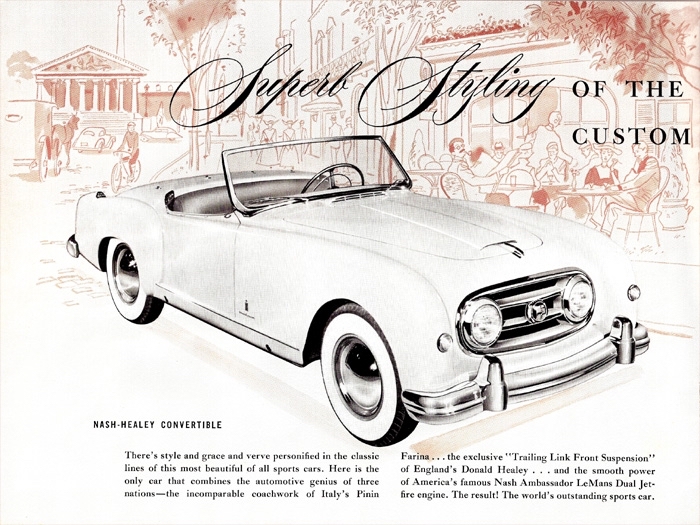

The Paris Motor Show in October 1950 was the scene of the introduction of the production car, now called the Nash-Healey. It had an attractive new aluminum body made by Birmingham’s Panelcraft Sheetmetal that eschewed the Silverstone’s cycle fenders with an envelope design penned by Len Hodges and Healey. For brand identification purposes, Mason insisted that Nash flagship Ambassador’s grille be used, much to Healey’s chagrin. He felt it was too large, saying that it reminded him of comedian Joe E. Brown, known for his enormous, elastic mouth. Healey made the grille of the Healey Sports Convertible, essentially the same car but with an Alvis engine for the European market, a bit smaller.

Had Healey known what Nash was going to do with the second-generation car, he might not have complained.

Production began in England in late 1950, with the U.S. introduction at the 1951 Chicago Auto Show. The Nash-Healey was available in either maroon or ivory paint, with leather upholstery and white sidewall tires that came standard. The car weighed 2600 pounds. Contemporary reviews said it had decent handling, tending to understeer due to that heavy six, and a comfortable ride, although the 10-inch drum brakes from the Ambassador were apparently not adequate enough for fast driving.

Nash dealers liked having a halo vehicle, but with an MSRP of $3767, it was about two-thirds more expensive than any other Nash. Just 104 were made for the 1951 model year. Only 20 are known to exist today, which makes them more rare than a Tucker.

While the Nash-Healey lost money for Nash, it helped get the Healey organization back into the black, providing funds for the development of what would become the Austin-Healey 100.

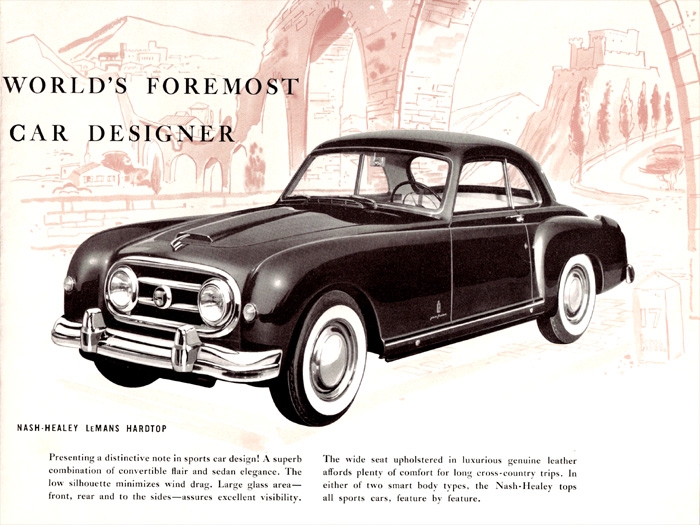

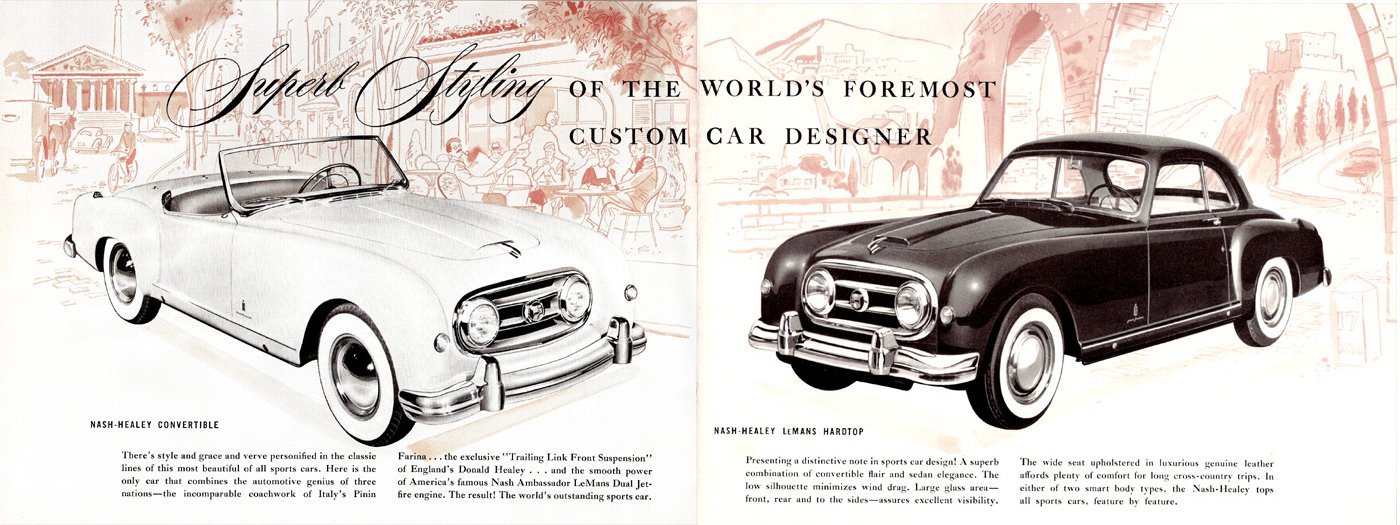

George Mason liked traveling to Europe for auto shows, since it allowed him to keep up with the latest from the continental coachbuilders. Healey was particularly impressed with Battista “Pinin” Farina of Turin, Italy. After returning to Wisconsin, Mason had George Romney, his protégé, hire Farina to consult on styling. For most Nash vehicles, the Italian stylist’s contribution extended to the Pininfarina badge on the fender, but he was apparently responsible for the second-generation Nash-Healey, introduced as a 1952 model.

The car, now a true convertible with roll-up windows, not a roadster, got a new front end with headlights inset into the grille, a motif that would appear on the 1955 Ambassador. Pininfarina designed some beautiful cars, but the second-generation Nash-Healey was not an improvement over the original. Because of how few 1951 models have survived, most people associate the name Nash-Healey, if they know it at all, with the later version.

The ’52 also got a one-piece windshield, some side contouring, and rear fender flares that kicked up into short tailfins. While engine power was increased, the bodies were now made of steel in Italy, not aluminum in England, which didn’t exactly help performance.

The 1953 model year brought a coupe version, but by then the Nash-Healey cost $5908 ($57,000 today), compared to $3513 ($34,000) for the new Chevrolet Corvette. Sales dropped almost in half, to just 90 units. Over the four model years, only 506 Nash-Healeys were produced, along with another dozen or so prototypes and race cars. The best year was 1953, when 160 were sold.

It wasn’t necessarily low sales, however, that likely doomed the project; after all, the Corvette only sold 300 units in its first year. Some estimates have had Nash losing more money on each Nash-Healey than either Ford or General Motors each lost on the Continental Mark II and Eldorado Biarritz, which means thousands of dollars. Ford and GM could write that off as the cost of prestige. A struggling independent could not.

The fact that its patron, George Mason, died suddenly in the fall of 1954 may have also been a factor in the car’s demise.

Still, as the Cobra and Corvette would prove, the Nash-Healey was a good idea, just one that was ahead of its time.