Media | Articles

Why the new Corvette doesn’t offer a manual transmission

After taking six decades to move the Corvette to mid-engine, Chevy ventured beyond clutch pedals without hesitation.

Corvette executive chief engineer Tadge Juechter tells those who bemoan the lack of a manual transmission in the new mid-engine C8 that requests for a dual-clutch automatic (DCA) began years ago. The stick-shift take rate, by the way, fell from more than 50 percent at C7’s 2014 launch to less than 20 percent this year. Add to that the DCA’s ability to upshift without interrupting power delivery, a feat no manual gearbox can accomplish.

Juechter also informs skeptics that a clutch pedal would cramp the C8 driver’s-side footwell, and that routing shift linkage through Corvette’s tubular aluminum spine would compromise its structural integrity. Instead of following tradition, his engineering team sought out and implemented functional improvements whenever possible. From our vantage, the new eight-speed DCA is progress every bit as significant as shifting the Corvette’s engine to the middle while keeping its base price below $60,000.

Blending the best manual and automatic traits

20191106200650)

Like stick-shift transmissions, DCAs consist of an electronically-controlled box of shafts and helical gears. One clutch remains engaged while the second clutch takes up slack during an upshift, a trait that mimics torque-converter automatics. While the entire shift process takes approximately 100 milliseconds, comparing that time to a quick shift in a manual transmission is fruitless because, unlike sticks, DCAs don’t interrupt torque delivery during gear changes.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Decades of dual-clutch engineering

20191106200656)

Efforts to contrive an automatic transmission with two clutches energizing a jumble of helical gears began in the early 1930s when Citroën tried to perfect such a design for its Traction Avant. After that attempt failed, the idea laid dormant until Hungarian Imre Szodfridt earned a patent for one in 1969. Porsche’s brilliant Ferdinand Piëch took notice, authorizing construction of a prototype gearbox logged as project 919 in Zuffenhausen’s scheme of things. Colleague Helmut Flegl recognized two potential DCA advantages: improved fuel economy, a pressing need following the 1973 energy crisis, and a means of maintaining boost during upshifts in Porsche’s turbocharged race cars since lifting off the throttle is unnecessary with DCAs.

After three years of testing and untold frustration, Porsche finally won a race using its PDK (Porsche Doppellkuplungsgetriebe) in a 962C at Monza in 1986. Seven years later, PDK was the exclusive transmission for 911 Turbo models and today it’s the most popular gearbox throughout Porsche’s entire range.

The American company BorgWarner also played a key role promoting DCAs. After BW demonstrated what it called DualTronic to European car makers in the early 1980s, Porsche teamed with gearbox maker ZF to develop PDKs for road use. In 1998, convinced that stick shifts would soon die out, BW sold rights to the husky T56 six-speed manual transmission it developed for the 1992 Dodge Viper to Mexican manufacturer Tremec. That firm promptly thrived as the go-to source for T56s for Camaros, Corvettes, Mustangs, and Vipers.

Corvette’s turn to revolutionize its transmission

20191106143340)

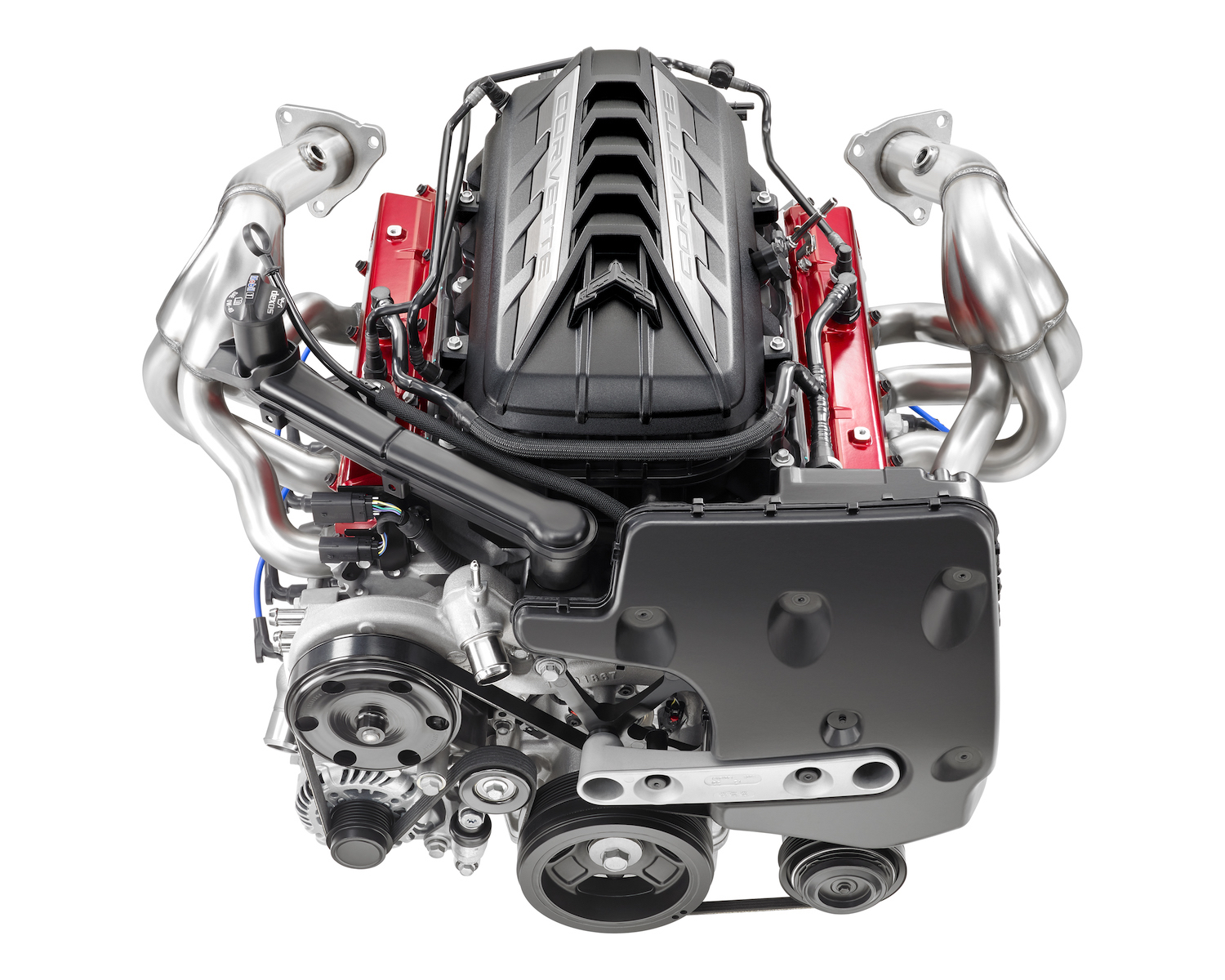

When GM emerged from bankruptcy a decade ago, Corvette engineers resumed work on their mid-engine design originally intended for C7. Searching for suitable transaxles, engineers found none with the right combination of torque capacity and affordability. Instead Tremec was encouraged to stretch its expertise beyond stick shifts into the emerging realm of DCAs. In 2012, Tremec bought Hoerbiger Drivetrain Mechatronics, located in Belgium, to add electronically-controlled actuators to its portfolio. Hoerbiger had exactly the expertise Tremec needed after supplying DCA components to European supercar makers AMG, Ferrari, and McLaren.

The Tremec TR 9080 eight-speed DCA collaboratively engineered for the C8 Corvette has two concentric clutches driving a pair of concentric input shafts. The outer clutch powers even-numbered gears located at the front of the transaxle while the inner one drives odd-numbered gears. A countershaft located above the input shafts carries mating gears in mesh and delivers torque to the final-drive differential via a transfer gear set, shaft, and spiral bevel ring and pinion. This layout—input at the bottom, output at the top—was chosen to facilitate mounting the Corvette’s LT2 V-8 an inch lower in the chassis than was possible with the LT1-powered C7. TR 9080’s dense design saves room for flowing exhaust pipes, catalytic converters, coolant tubes, and the rear luggage compartment.

20191106143346)

Eight forward speeds provide plenty of torque multiplication for aggressive launches, a super-tall gear for quiet cruising, and six gears between those extremes to keep the engine spinning at fruitful rpm during acceleration. No gears are missed accelerating to the 0.33:1 eighth gear but intermediate ratios can be skipped during an aggressive downshift. While the TR 9080 has a maximum torque capacity of 590 lb-ft and is limited to 7500 input rpm, Tremec acknowledges that DCAs with additional capability are under development.

Unprecedented control modes

20191106143318)

Corvette engineers compensated for the supposed loss of driver involvement with control knobs and buttons beyond the usual shift paddles. The Driver Mode knob on the console adjusts 12 performance variables to suit six traction options displayed in the instrument panel screen and in the (optional) head up monitor: Tour, Sport, Track, Weather, My Mode, and Z-Mode. The latter two choices provide additional flexibility in configuring the engine, transmission, and display setting to the driver’s liking. A discreet Z (for Zora) button on the left steering wheel spoke allows the driver to instantly engage pet preferences. Two taps of a toggle ahead of the Driver Mode knob shuts down all traction and stability assistance, confirming that the driver wants every bit of performance the new Corvette has to offer.

Those interested in experiencing the Corvette’s burst of enthusiasm from rest to the speed of their choice should first warm the rear tires in the aptly titled burnout mode: engage Drive, hit the brake, pull back both shift paddles, floor the accelerator, then release the brakes and the shift paddles to smoke the tires to your heart’s content. That should be promptly followed by launch control which works in both D and M shift modes: left foot on the brake, right foot deep into the throttle, then lift off the brake while flooring the throttle as soon as the tach registers 3500 rpm to break the 3.0-second barrier on your rush to 60 mph. According to Chevy, a C8 with the optional Z51 Performance Package does that deed in 2.9 seconds versus 3.0 for a base edition. Quarter-mile ETs are the same for both at an astonishing 11.2 seconds. The trap speed king is the lower drag base model at 123 mph versus ‘only’ 121 mph for the spoiler adorned Z51.

Manual trans withdrawal syndrome

20191106145624)

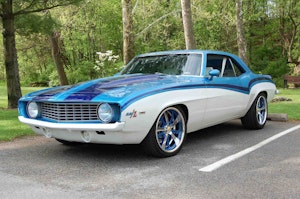

Of course there will be Corvette fans convinced they can’t exist without a classic clutch pedal and H-pattern shifter. Their salvation might be purchasing one of the thousands of leftover C7s Chevrolet dealers have in inventory now that C8 is poised for production beginning next February. Based on past experience, the holdouts will join the DCA throng once their peers acknowledge that life indeed goes on without clutch pedals.

20191106200624)

20191106200629)

20191106200634)

20191106200638)

20191106200643)

Girly man car.