For this ’88 Countach owner, tinkering under the hood is part of the sensory feast - Hagerty Media

Even as a ranch kid growing up on the Great Plains in eastern Colorado, Victor Holtorf had an engineer’s mind. Insatiably curious about how the world worked and how it was designed, he looked for any excuse to take apart any object if it would allow him to better understand how it functioned. Fortunately for young Victor, life on a ranch gave him ample opportunity to do just that, as there was always something—carburetors, pickups, machinery—in need of repairs. Once he reached driving age, Holtorf’s incurable urge to tinker and tune spread to his cars.

By the time Holtorf finished engineering school and showed up in California’s Silicon Valley in the early 1990s, he was an accomplished automotive mechanic, although his skills and tastes leaned more toward the muscle cars that had filled his youth in Colorado, especially his beloved Buicks. Soon, however, he found himself buying vintage foreign cars—first Lotuses and then Lamborghinis. As he did so, an entirely new world opened itself, one in which the coequal concerns of engineering and design informed every aspect of the car.

“The Italians have a long history of art and beauty that the American manufacturers just didn’t pursue to the same extent,” Holtorf says. “You pop the hood on a Chevelle, there’s a motor. It’s cool, but the valve cover doesn’t intrigue you, whereas these Italian cars are so highly engineered. They’re high tech for their day, and they’re also beautifully built.”

Holtorf found solace in these exotic machines. While his co-workers might head out to the clubs of San Francisco after a hard-charging day at the office, he is more inclined to head down to the warehouse he had rented in an industrial suburb and work on his cars. The hours disappeared as he tore down Italian V-12 engines, marveled at the intricacy of their design, and reassembled them in pursuit of improved performance. These nights in the shop became his refuge from the intensity of dot-com-boom-era Silicon Valley.

“It was almost therapeutic to take [an engine] apart, figure out how they made it, and be fascinated with the engineering that went into even something like a little faster,” Holtorf says.

Holtorf had always wanted a Lamborghini Countach. Like so many kids of his era, he had that legendary Alpine Stereo poster of the Countach on his wall. You know, the one with the big wing and fender flares—the poster that made that Countach the Countach for every kid born after 1975.

Holtorf’s car dreams were also shaped in great measure by the opening scene of Brock Yates’ Cannonball Run.

“I wasn’t sure if I loved the car or the girls more. It was all just amazing to me,” Holtorf says with a laugh. “The girls were great. The car was great. As a young kid, that whole scene was everything.”

And when he could afford a Countach, that’s the car Holtorf wanted. The wing, the flares, the garish 1980s fighter jet styling… all of it. His friends, however, steered him toward the earlier, and more rare, LP400 model.

“Many older collectors told me you want the first one,” Holtorf says. “It’ll be the most valuable. It’s the lightest weight. It’s the purest. It’s the rarest, and you’ll love it. And then you can always buy your flared childhood dream one later.”

He got the LP400 in 1992 (and still has it), and he did indeed love it immediately, but he never gave up his dream of that later Countach. It took Holtorf another decade, but he finally found the perfect bookend to his LP400.

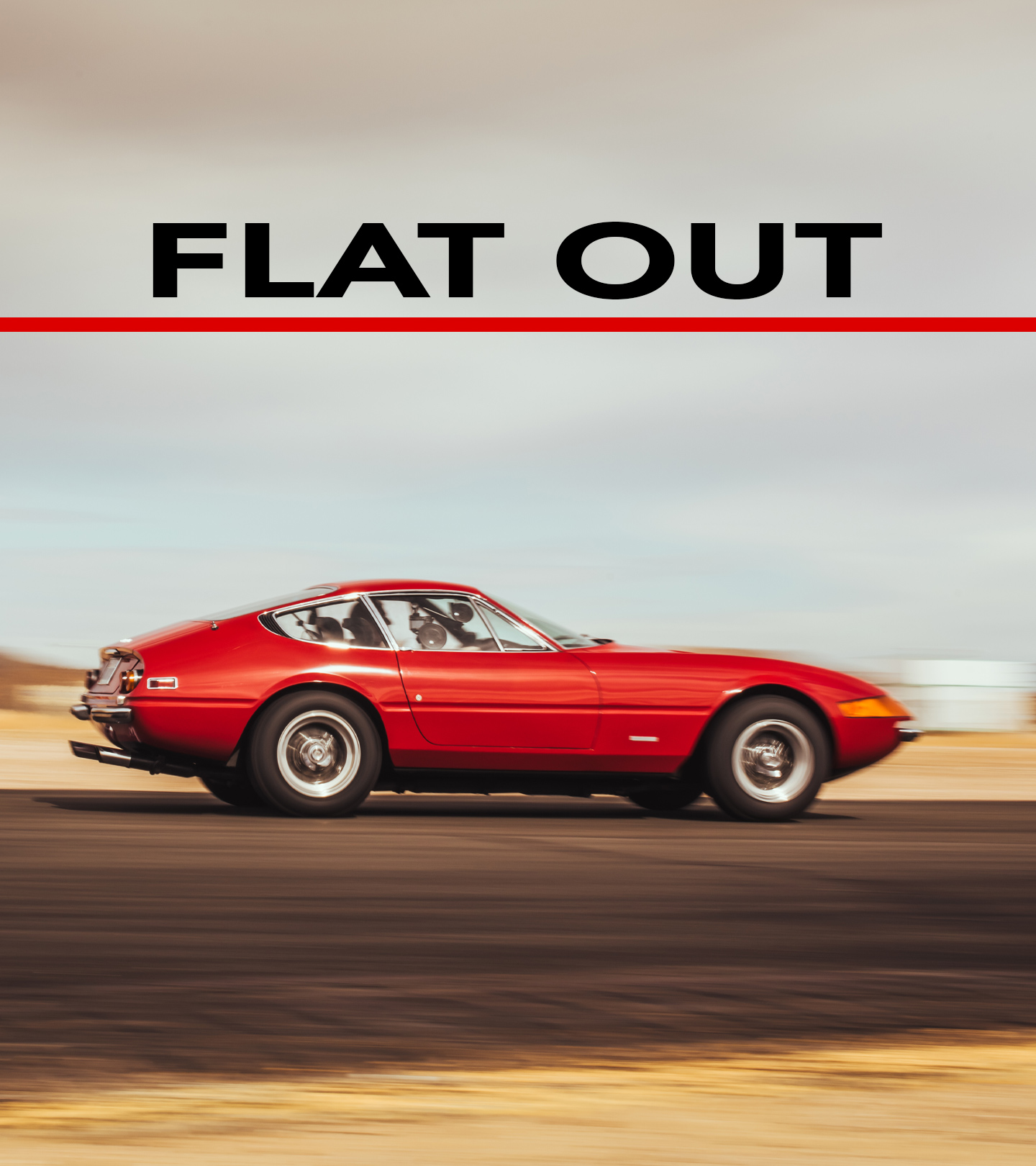

In total, Lamborghini made nine different variants of the Countach. The first one was that LP400, which debuted in 1974. The car featured in this episode of Hagerty’s Why I Drive, a 1988 model, is one of two final variations. Lamborghini produced a fuel-injected model for the U.S., but Holtorf’s car is a carbureted European car, which features six downdraft Webers and four valves per cylinder—all of which yielded the highest-horsepower Countach ever produced and made it, at the time, the fastest production car available.

“I love carburetors,” Holtorf says. “I know fuel injection is better for a lot of reasons, but with a carburetor you have instant throttle response. There’s not even a fraction of a second delay when you push the throttle and something happens. Plus, you can hear [the carburetors], and sometimes you smell the gasoline when you really get on the gas hard and all the pumps are shooting the gas in. It’s a sensory feast.”

Granted, driving this car—as Holtorf frequently does on the Rocky Mountain roads that loom just outside his back door—is equal parts exhilarating and exhausting, but that’s exactly the way he likes it.

“If you look at the engineer’s plans when they were designing these cars, nowhere does it say ‘Mission Statement: Point A to Point B,’” Holtorf says. “Doesn’t say that. It’s about fun. It’s about passion. It’s about sport, about exhilaration. It’s about sensory inputs. It’s about the thrill.”

And yet, as much as he enjoys driving these cars, Holtorf, ever the engineer, continues to return to the joy of working on them. On any given day, he can be found in his shop in Fort Collins, leaning over the engine bay of a Diablo or Countach or Esprit, engrossed in the intricacies of these machines.

In these moments, the world of ranch life and Buicks seems far away, but the same curiosity that kickstarted Holtorf’s automotive adventures continues to fuel him to this day.