Media | Articles

Wandering the hallowed, abandoned halls of the Bugatti EB110

For all his life, Enrico Pavesi has lived next to the field where Bugatti’s Italian factory took root, so he knows the story better than most. Since Bugatti’s plant sprung up on the side of a busy freeway near Modena, Italy, in 1990, Pavesi’s family has diligently looked after it. His family is intertwined with its history, arguably doing more to keep Bugatti’s obscure Italian heritage alive than anyone else.

“We still get mail from people who don’t know the factory closed. They send us their resume, or sketches that they’ve drawn, and ask if we can give them a job,” Pavesi tells me as we walk into the abandoned glass-walled building in which the Bugatti EB110 once came to life.

Pavesi’s father, Ezio, was hired as a groundskeeper in 1990. He brings the backdrop to life as he weaves through the rise and fall of Bugatti’s infamous Blue Factory in Campogalliano.

From flammkuchen to pizza

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Locals still speak the name of industrialist Romano Artioli with near-superstitious awe. He is the man who purchased the rights to the long-dormant Bugatti brand in 1987 and commissioned the factory the following year. Although Bugatti was founded in Alsace, France, he chose to base the born-again automaker in a small, quiet town on the outskirts of Modena, in the area where several other companies were already peddling exotics. You might have heard of them.

From behind his desk, he could nearly hear a Ferrari F40’s mighty turbochargers whirring away as it sped out of the company’s headquarters. Lamborghini manufactured the scissor-doored, V-12-powered Countach a little bit farther away, and it tested each example on the cypress-lined roads Artioli might have driven on to take his family out to gelato. His goal wasn’t to play follow the leader, though. He wanted to tap into the Italian Motor Valley’s vast talent pool and benefit from its latticework of suppliers well-versed in making parts for high-end cars. Alsace has great wine, and the flammkuchen in Strasbourg is at least as good as the pizza in Bologna, but Bugatti’s traditional home region offered none of the advantages of Italy’s Emilia-Romagna.

Working closely with architect Giampaolo Benedini, Artioli envisioned a state-of-the-art industrial complex designed around the people working in it, not around the product it built. Glass walls let natural light in, and air conditioning—a rare luxury in Italy at the time—kept the temperature in check. Never an elitist, Artioli ran Bugatti from a small, modestly-appointed office, and normally ate in the same cafeteria as assembly line workers, even if he was hosting guests like Michael Schumacher.

Artioli accomplished a lot with a little. He successfully launched production of the EB110, an often-forgotten supercar that pelted Bugatti into the modern era and laid the foundations the Veyron and the Chiron stand on. He planned several follow-up cars, including a super-sedan tentatively called EB112, a United States-bound model aptly called America, and he also purchased Lotus from General Motors. The Elise is notably named after his granddaughter Elisa.

His empire wasn’t future-proofed, and it crumbled in the middle of the 1990s. Some say he bit off more than he could chew with Lotus, while others argue the economic downturn that swept across Europe and the United States drove the final nails into Bugatti’s coffin. To an extent, both arguments are valid. What’s certain is that Bugatti filed for bankruptcy in 1995 after making 128 examples of the EB110. Germany-based Dauer purchased the remaining stock of parts and made four additional cars.

Italy’s shrine to a forgotten supercar

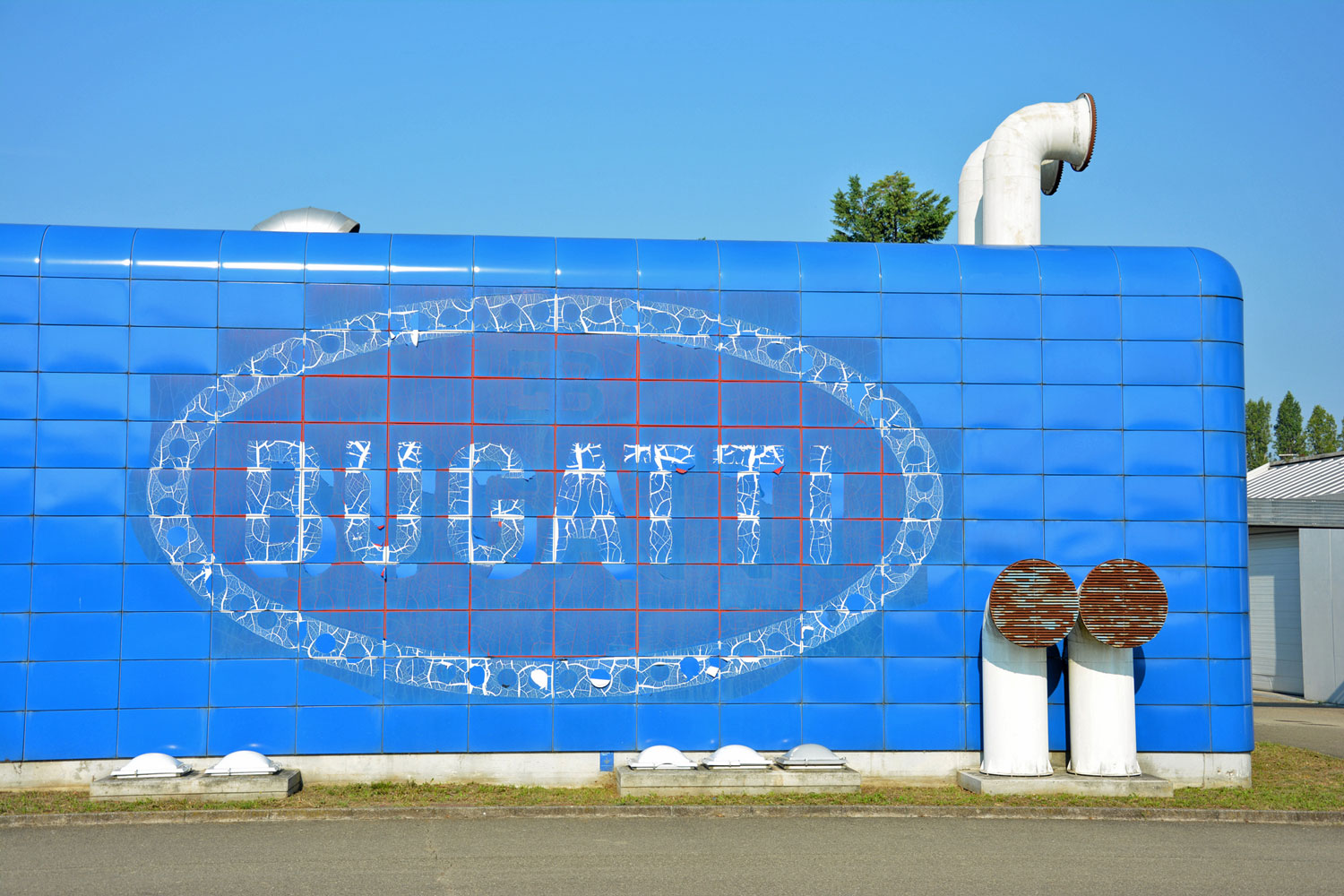

The Blue Factory hasn’t changed much since it produced the last EB110. Artioli’s old bicycle is still in the lobby, which I found out when I innocently borrowed it, not knowing that. Anyone driving past the factory can see what’s left of the huge Bugatti logo. It was covered up with blue stickers after Volkswagen bought the rights to the brand in 1998, but it’s slowly emerging as it bakes like a tomato under Emilia-Romagna’s scorching sun.

Photos showing the factory during better days line the walls in nearly every building. They help visitors listening to Pavesi’s captivating tales put together a puzzle that would otherwise be left entirely to their imagination. The factory is almost empty, so it’s difficult to picture a V-12-powered, 560-horsepower supercar coming to life there.

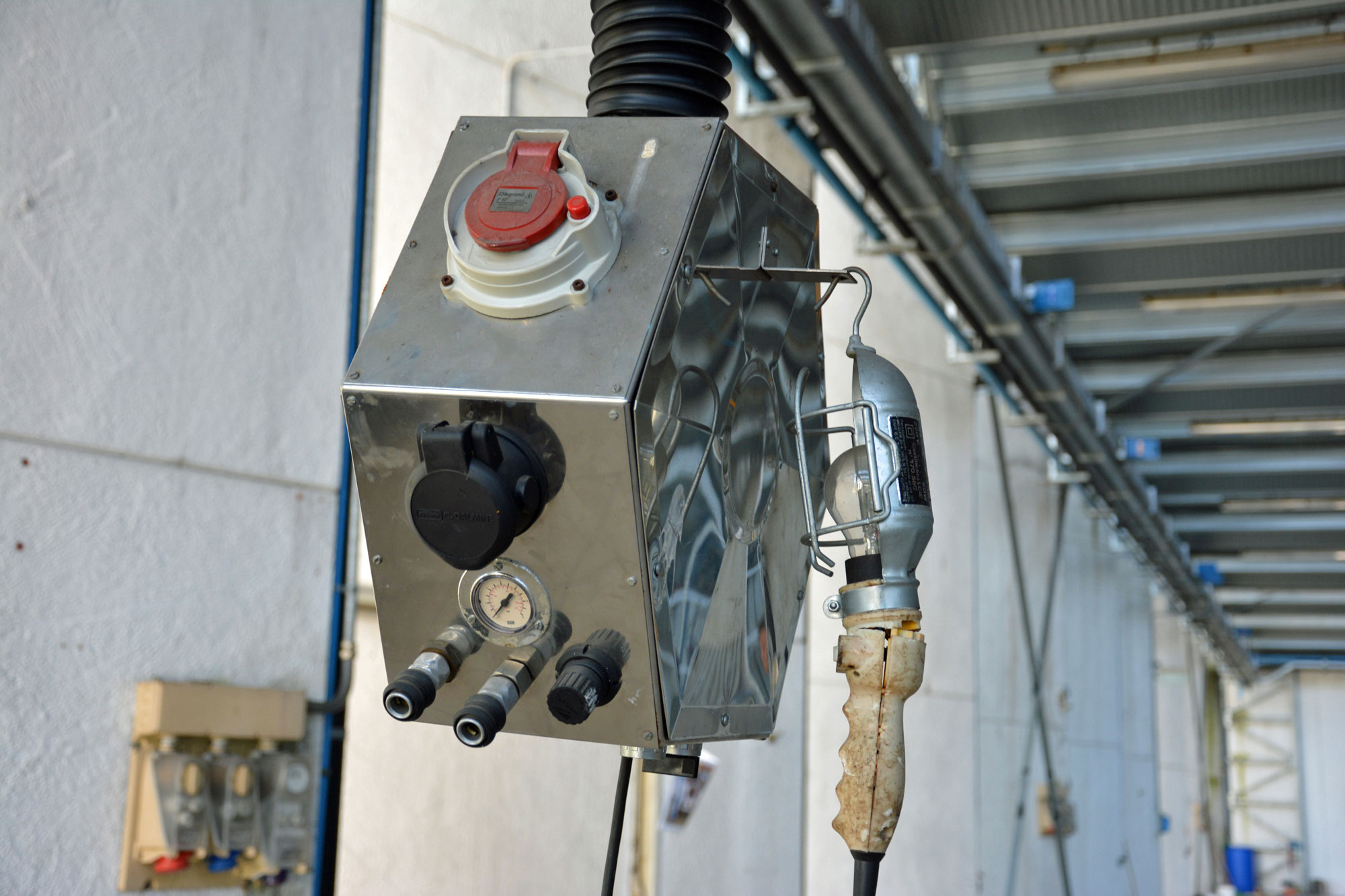

In the main hall, Pavesi points to where the quad-turbocharged engine was meticulously assembled, to where the EB110’s body was carefully put together, and to the point where they became one unit. The sound-proof box that every car was tested in before flexing its muscles on asphalt stands proud as a reminder of the effort Artioli put into making the facility a comfortable place to work in, even for blue-collar employees.

Time froze in the design center. Calendars from 1995 pile up. IBM computers made when half of Germany still buzzed around in Trabants gather dust, while buckets used to collect rainwater until Pavesi repaired leaks in the roof are stacked in the middle of the room. Here again, photos show the round, glass-walled design center in its heyday.

In true Italian fashion, the facility’s soul was, perhaps, the cafeteria. Bugatti was small in the 1990s, smaller than it is today under VW Group’s corporate patronage, so the entire workforce convened as a team—or, by some accounts, as a family—and ate together. Photos of concept cars still line the wall; they’re glued on by humidity and can’t be removed.

Some of the more mobile bits and pieces of the Campogalliano factory outlived Bugatti’s second coming. Pavesi told me that tractor manufacturer Goldoni purchased several assembly line machines and used them until 2017. Many of the local companies that bought the cafeteria tables still use them in their offices as of 2019. And, someone presumably still has the statue of Ettore Bugatti’s head that was stolen from Artoli’s former office many years ago. Thieves used to wander into the factory on a regular basis, but the break-ins have stopped. By now, word has spread that there’s nothing left worth stealing.

What’s next?

For better or worse, the factory has almost been saved several times since it built the last EB110 in 1995. Liquidators sold the property to a furniture manufacturer who filed for bankruptcy before moving in. Pavesi told me there was a serious attempt to turn Campogalliano into a mall in the early 2010s. Interestingly, developers would have needed to keep all of the buildings intact, which would have made for a unique shopping center. The project fell through in 2011 when money ran out—I’ll pause here so you can recover from the shock of this news.

The Pavesi family still hopes someone will purchase the factory and build something there while honoring its heritage. Enrico admits, however there are no ongoing talks as this moment. What’s certain is that its next owner won’t be Bugatti. “We are ultimately guests here, too,” a Bugatti spokesperson reminded me. “Our home is in Molsheim. Buying Campogalliano isn’t even a consideration.”