Media | Articles

Where Hollywood’s movie car people get their inspiration

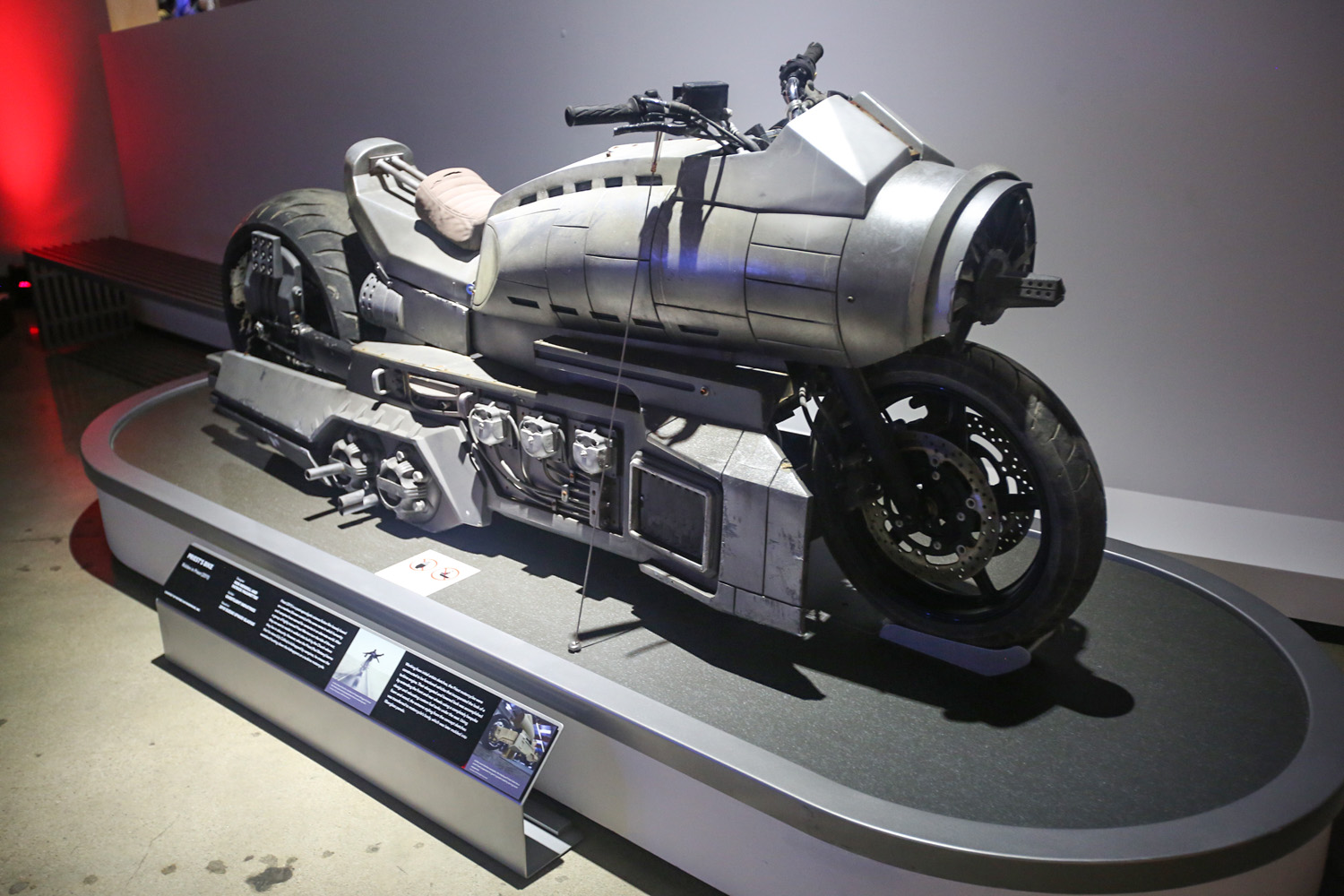

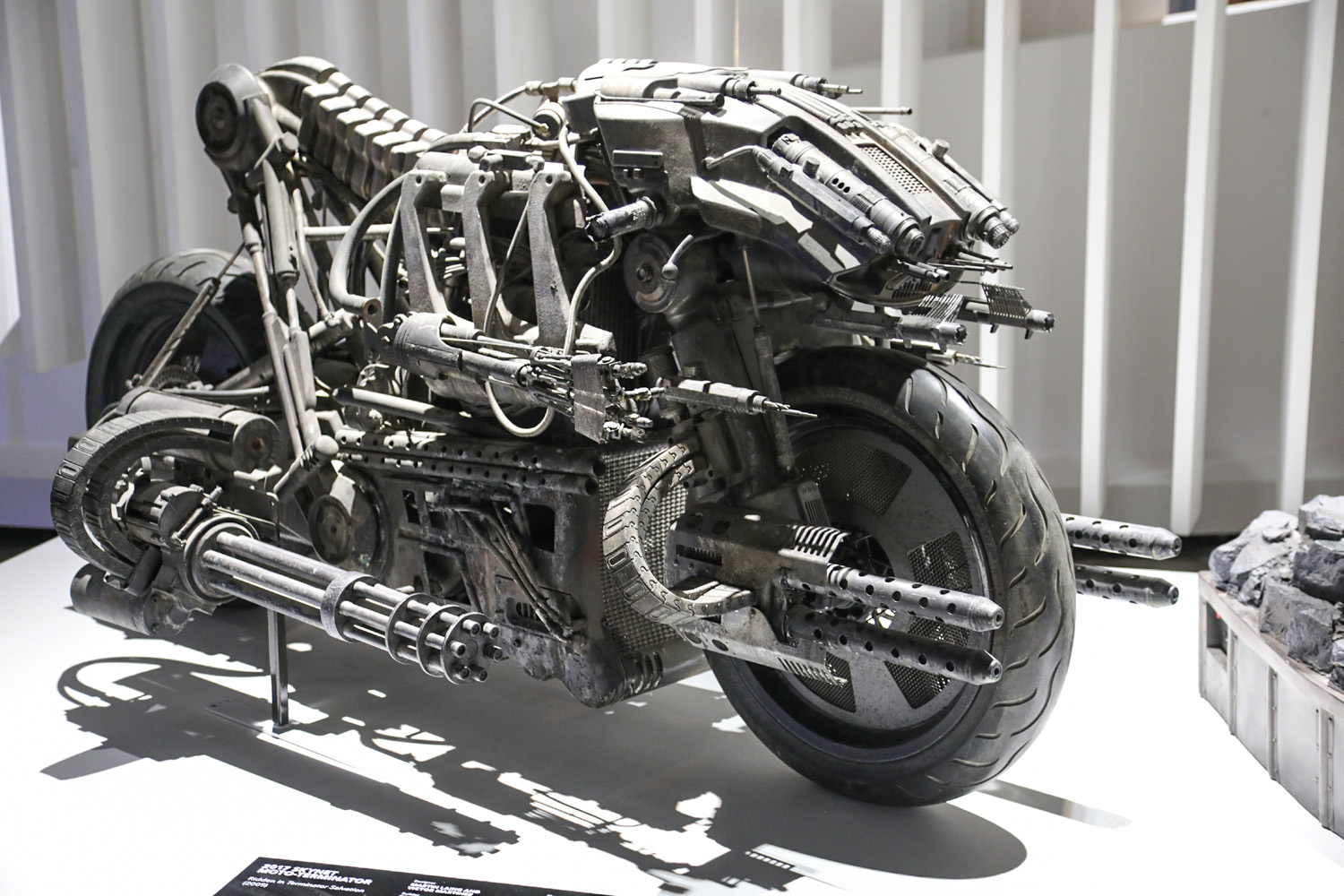

There are movie cars, and then there are the creative minds behind the movie cars. To showcase its new exhibit, “Hollywood Dream Machines: Vehicles of Science Fiction and Fantasy,” Petersen Automotive Museum brought some of those people together to share their influences, automotive creations, and opinions about where the movie industry is headed.

The illustrious panel, moderated by film critic Scott Mantz, included art director and production designer Michael Scheffe (Back to the Future, Knight Rider), entertainment automotive expert and host Josh Hancock (Casino, The Rainmaker, the Austin Powers franchise, John Wick: Chapter 3, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood), picture car coordinator Dennis McCarthy (Batman Begins, Captain Marvel, Black Panther, Avengers: Endgame, The Fast and the Furious franchise), automotive designer Harald Belker (Batman and Robin, Minority Report, Tron: Legacy), concept artist and designer George Hull (Constantine, the Matrix sequels, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, and Blade Runner 2049), and award-winning screenwriter, director, producer Bob Gale (co-creator of Back to the Future).

Here are the highlights from the discussion.

Inspirations

Scott Mantz asked the panelists about their favorite movie vehicles, which evolved into a discussion about the cars that inspired them to pursue their careers. They shared a disbelief—not just that they’d attained their dream job of working on movie cars, but that these jobs exist at all.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The first car that excited Michael Scheffe was the AMT Piranha from The Man From U.N.C.L.E. But it was when he saw George Barris’ Batmobile that it finally occurred to him, “Oh, someone had to build that for this show; that’s a pretty good job, right?”

I never dreamed when I grew up, more or less, that I would ever have a hand in any of that stuff…” said Scheffe. “The impression that that stuff leaves on you when you’re young and you have an open mind and you’re not so cool that you’re not impressed… it leaves a big mark, right? It really, really does.”

Harald Belker also alluded to the Batmobile as one of his influences. After studying automotive design at Art Center like Scheffe, Belker had an opportunity to get into film. “My world just exploded with the possibilities you have in film—unlike automotive design, which was very limited, very corporate, and sort of never looked back,” said Belker. “And then you’re just a 10-year old dreaming every day and coming up with the coolest things.”

For Dennis McCarthy, it was The Dukes of Hazzard. “Just seeing that Charger flying through the air was one of the coolest things ever,” said McCarthy. “It’s just that I’ve always been drawn to movie cars, and I never really thought that I would end up in this business, and I really did by chance. I feel really lucky today to get to play with all this stuff. We build cars, we go out, we test them, we push them ‘til they break, and hopefully show up on set with the perfect product. It’s one of the greatest jobs ever if you like movie cars.”

George Hull shared his love for Blade Runner, which came full circle when he was hired to work on Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049. When Hull saw Ridley Scott’s film for the first time, he said, “My brain exploded. The spinners, the flying cars, Harrison Ford in this dystopian world. The environments, the cars, the invention, all that coming together just completely changed my world.”

Hull wondered, “How do I get to do this? I grew up in Ohio, completely away from Hollywood, and I saw that these were industrial designers that did this for work, so I went to a state school. I was working on vacuum cleaners and really boring stuff, and I thought that’s never going to be a reality.” When Hull got the call to work on Blade Runner 2049, he was on his lunch break—sketching spinners on a napkin.

Josh Hancock said the Munsters’ car did it for him. “It was like I would die to see that car,” said Hancock. “And then Grandpa had a coffin that he drove, and the Beverly Hillbillies drove around in that car. But I was also fascinated with cars so young that when Chrysler introduced new cars, Mr. Drysdale [of The Beverly Hillbillies] would drive up in a 300 convertible. I was like, ‘That’s a new 300 convertible!’ And my father would go, ‘OK, nice, great, wanna play football?’”

Finally, Bob Gale pointed out a surprising omission from everyone’s list of influential cars: “James Bond’s Aston Martin [from Goldfinger]. I had a model kit. Every kid wanted to have that car.”

Commitment to character and story

What unites each car designer is their absolute commitment to story, ensuring that each vehicle fits the film’s universe and reflects the character who drives it. Scheffe, who built KITT, explained, “We were really careful to try to keep the feeling of the design [of the Trans Am]. These guys have talked about how important it is for a car, any vehicle, any prop, it plays a role in telling the story, and in Knight Rider it is a character itself. It talks. So how does it help tell that story?”

There are vastly different considerations in designing a vehicle like the DeLorean in Back to the Future, which needed to look like a “crazy guy built it in his garage,” versus a car like KITT, where money was no object. As for the choice to cast a Trans Am as KITT, Scheffe thought the decision was smart because, “that car was on the cover of every car magazine before it came out because no one could wait to see what it was, and everyone’s got their hopes pinned on it. Maybe here’s an American car that will really perform well, and it’s gorgeous and it’s fast and it’s wonderful.”

McCarthy also stressed the relationship between cars and characters: “I always try to tie the cars into the characters—Acura was the car that came to mind for Mia [in The Fast and the Furious series] this time.” Considering the Charger is Dominic Toretto’s favored car, Dodge has “always been a huge supporter of the franchise, and it’s very organic.” He added that it is “really the key to product placement—it has to be organic. You don’t want to place the wrong car with the wrong person just because there’s money behind it, and granted it depends on the project; sometimes you’re forced to do that. But The Fast and the Furious, being that it is a car-driven franchise, we never do that… My goal at the end—if you see the car onscreen the fans of the franchise will know, that’s gotta be Tej’s car, or Roman’s car. You have an idea before the door opens and the character gets out, you know whose car it is, so that’s what I strive for.”

How product placement has changed

A member of the audience asked about product placement, wondering specifically about Avengers: Endgame, and whether anyone had a sense of how much Audi ultimately paid. Hancock explained, “It’s less than you’d think in terms of raw cash. They ask now [for] companies to pay for premieres; they ask them for print and ad money. There’s a lot of barter that goes back and forth.” The cash deals just don’t happen as often as they used to. Now they “provide different things in the movie, they help costs, and then it’s about a cold marketing campaign. It’s a very different thing that’s product integration, and a cold marketing campaign costs millions of dollars because they’re going to tie it into advertising and that’s what the studio is looking for. Production is looking for saving money on the production, which means, yes, pay for our premiere. It’s little things, but it adds up.”

Belker added that, although it may not be much, “it’s also enough that people like me don’t get hired.” Belker worked on the first Iron Man designing a car that Tony Stark had built himself, which complemented his suit. Belker worked on it for four months—until Audi arrived. “I get the call to the big office and they go, ‘So how much is that going to cost?’” Ultimately, it was too much. “The next day they told me that Audi moved in and gave them a certain amount of money and left me walking away.”

When product placement goes bad

Hancock recounted a couple of the worst examples of product placement: “When they brought Knight Rider back and they put him in a Mustang. They were great cars, but it was a different show.” Belker interjected, “I got to design that one, by the way.” To which Hancock quickly replied, “I did love the Mustang. It was great. It was beefier…” (Someone called out, “Good save!”)

Bad product placement likely killed the Knight Rider comeback, and it nearly sabotaged Back to the Future. While they were working on the film, Gale received an offer—a guarantee of $75,000 for the company, which in 1984 was a day-and-a-half’s worth of shooting. Gale asked, “What’s the deal?” They told him, “If you change the DeLorean to a Mustang, Ford Motor Company will write you a check.” Gale said, “I just looked at them and said, ‘Hey, Doc Brown doesn’t drive a friggin’ Mustang.’” If it hadn’t been for Gale making the right call for the film and its characters, the time machine may have been a much less memorable vehicle.

Hancock also brought up a sequence in the first Thor, which contained an outrageous number of Acuras: “There’s a scene in Thor with all these Acuras and everyone’s like, ‘What are these Acuras doing here, is there a sale? Did we break and go to commercial in the middle of the film?’” The product placement made no sense. Acura was “hungry to get into Hollywood,” and it had prepared “to do this big promotion with the dealers,” Hancock said. “Of course, it didn’t work because it wasn’t organic.”

Updating the classics

When asked how it feels to work on iconic vehicles like the Batmobile or Blade Runner’s spinners, the panelists talked about how designers collaborate with filmmakers, how to advance, evolve, and update vehicles, and what was sacred about them that they needed to preserve versus what they could play with. Belker explained that it’s not always up to designers to come up with something on their own, because they have to meet the needs of the director and production designer. “At some point they’ll trust you,” Belker said. “They’ll let you go, but it’s their vision originally and then you put your take on it.” Barbara Ling wanted Belker to design a Batmobile for Batman & Robin that had big fenders, a glossy single-seater. This Batmobile was also 28 feet long and had fins, and Belker admitted, “I wasn’t crazy about the fins in the back, so I kind of dismissed them, but [director] Joel Schumacher “made the call—‘I love fins’—and so fins it was. It just evolved.”

Hull countered that filmmakers often give their designers creative freedom. When he worked on Blade Runner 2049, he studied the work that his predecessors had created for the original Blade Runner, but he considered the new universe that Denis Villeneuve had created. “These [vehicles] are built to live in a dystopian world, and in 2049 it was even more apocalyptic.”

Blade Runner 2049 is set 30 years after Blade Runner, and there’s snow, extreme pollution, and in the time between the first and second film, Deckard set off an EMP bomb. Said Hull, “In movie design you’re always trying to look for the story—how to design with the story; form follows function. The director had keywords like ‘brutalism’ and ‘paramilitary,’ and you make this big stew, and you try drawing sketches of one that’s more crazy and more like a car and more paramilitary, and then you just try to figure out which recipe is gonna work the best.”