Media | Articles

Jerry Wiegert and the saga of the star-crossed Vector supercar

Weeks before I meet Jerry Wiegert, creator of the spectacular but star-crossed Vector W8 Twin-Turbo, we communicate via emails, snail mail, texts, phone messages, and prolonged phone conversations. So even before we get together, Wiegert has informed me that he invented the modern supercar (along with the personal watercraft, minivan, and four-wheel ATV), was put out of business by Indonesian gangsters who’d bribed members of his board of directors, packaged the deal that wrested Lamborghini away from Chrysler, and inspired the twin-turbo motor in the Ferrari F40 and the roadster version of the Lamborghini Diablo.

[This article originally ran in Hagerty magazine, the exclusive publication of the Hagerty Drivers Club. For the full, in-the-flesh experience of our world-class magazine—as well other great benefits like roadside assistance and automotive discounts—join HDC today.]

So I’m not sure what to expect when I arrive at Wiegert’s sprawling house in San Pedro, California, which overlooks the calm waters of the Pacific. I park behind a black Chevy Tahoe with a vanity license plate reading VEXTOR and wonder: Am I going to find a misunderstood genius who’s gone unappreciated in his own land? Or does Wiegert have more in common with another polarizing visionary, Steve Jobs, who was said to have operated in a reality distortion field that allowed him to convince himself—and others—that just about anything was true?

Wiegert opens the front door and greets me with a broad smile and a firm, meaty handshake. He’s a large, barrel-chested man, and it’s easy to imagine him as the high-school quarterback he once was. The suits and cowboy boots I’d seen in period photographs have given way to loafers, jeans, and a form-fitting athletic shirt, but he’s remarkably well-preserved for a man in his mid-70s. He exudes energy and enthusiasm. “I’ve still got a lot of miles left on the chassis,” he says with a laugh.

He leads me to a sunken living room next to an open kitchen full of upscale appliances. Strewn amid the high-end, mid-century-modern furniture and Wiegert’s own accomplished paintings and sculptures are Vector paraphernalia—models, magazine covers, license plates, photos, renderings. “Vector was the world’s first supercar,” he says, daring me to disagree. “Everything else was a sports car or an exotic sports car, not a supercar. They weren’t high tech or state of the art. I designed the whole car—the body, the chassis, the instrumentation, even the paint. Nobody else did that. They all had a bunch of guys who had a hand in their cars. There’s nothing wrong with that, but I wanted to be the architect—for the skyscraper, the yacht, whatever—without having a lot of interference.”

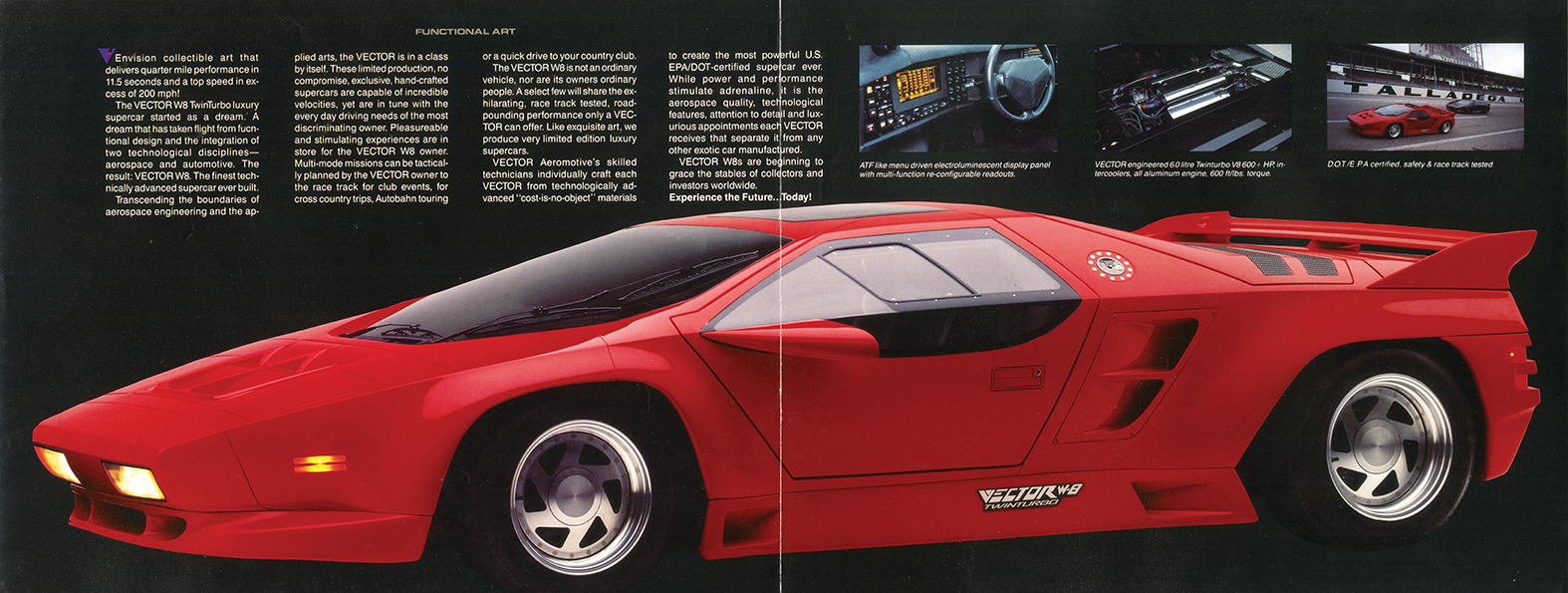

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The epic tale of the Vector is essentially the life story of Gerald A. Wiegert, a dazzling and protean designer who has displayed Herculean tenacity in the face of unrelenting calamity. The first Vector concept appeared in 1972, and it took nearly a decade for Wiegert to raise enough money to build a running prototype, and another decade before he amassed enough capital to put the car into production. Designed and built entirely in the United States, the nearly $300,000 W8 ticked every box on the high-performance checklist: a semimonocoque chassis, a mid-engine architecture, scissors doors, and a top speed claimed to be north of 200 mph. But it defied convention with its 625-hp, twin-turbo pushrod V-8 and three-speed automatic, both mounted transversely, as well as uniquely sinister-looking Kevlar-and-carbon-fiber bodywork that bore a not-coincidental resemblance to an F-117 stealth fighter on billet wheels.

“There was no compromise,” Wiegert says. “Everything was the best. There was no cheating. Ferraris and Lamborghinis had cheap seats. Vectors had the best seats—all electronic, inflatable lumbar, power backs, heaters. Vectors had mil-spec wiring and tactical military aircraft switches. They had Bosch sound systems, which were beyond anything ever put in a car before. We didn’t have to crash-test three or four cars. One car passed every single crash test at the highest levels—rollover tests, side-impact tests, all of that. It was considered the safest car that had ever been tested. I had this attitude that the Vector was going to be superior to Ferrari, Lamborghini, and Porsche. And it was. Fact.”

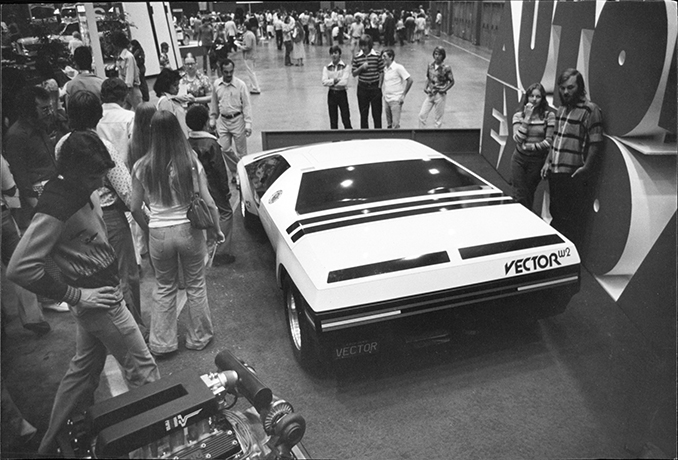

The cover of the April 1972 issue of Motor Trend featured an otherworldly, origami-like sports car that looked like fallout from the “wedge wars” that had been raging in Europe since the late 1960s with concept doorstops such as the Alfa Romeo Carabo, the Ferrari Modulo, the Lamborghini Countach, the Mercedes C111, and the Lancia Stratos HF Zero. This one, however, exuded its own Yankee muscularity. “Vector: U.S. Challenge to Italian Styling,” read the caption. There wasn’t much about the car inside the magazine because the car was little more than a fiberglass shell over a derelict Porsche chassis. No engine, no drivetrain, no interior. But the styling was breathtaking, from the gigantic windshield and deeply sculpted intake ducts to the exquisite olive-green paint. The Vector immediately transformed the young, unknown Wiegert into a name in the burgeoning exotic-car industry.

Born in the shadow of Ford’s headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan, to a machinist who could build just about anything, Wiegert inherited his father’s mechanical aptitude and love of vehicles for land, air, and water. While he was in 10th grade, he gathered his first carbuilding team and transformed a humdrum 1954 Chevy into a wicked-fast B/gasser. He then attended the Center for Creative Studies in Detroit, did an internship at the General Motors Tech Center, and graduated from ArtCenter College of Design, then in L.A. He spurned an offer to return to GM “because, frankly, I didn’t want to be a yes man.”

Wiegert remained in Southern California and worked on the design of everything from toilets to Grand Prix motorcycles, rocket belts to personal watercraft. He helped set up Toyota’s Calty Design Research studio in California and even served as a consultant on the 1983 James Bond flick Never Say Never Again. Aerospace was his passion; the greatest disappointment of his life was that his poor eyesight prevented him from becoming a fighter pilot. Cars were where he figured he could make his biggest mark, and that’s because he had a big idea—namely, leverage leading-edge aerospace technology to create an all-American supercar that would eviscerate the Ferraris and Lamborghinis of the day.

In 1971, Wiegert fashioned a one-fifth-scale foam model of what would soon become the original Vector. He then persuaded Lee Brown, owner of Precision Auto Body in Hollywood and panel beater to the stars, to partner with him on building a full-size car. Brown agreed to provide a Porsche chassis to serve as the foundation of the prototype. Brown also had a flat-six motor that was supposed to be mounted amidships. However, during the thrash to ready the car for Auto Expo 72, an influential L.A. show devoted to specialty cars, there was no time to install the drivetrain. Before the car was finished, Wiegert had a falling-out with Brown—a theme I would hear repeated several times during our conversations—and Wiegert lost possession of the car after its star turn at Auto Expo. The episode taught the would-be entrepreneur two lessons. The first, Wiegert says, was “that I was never going to have another partner. If I wasn’t in charge of my own destiny, I wasn’t going to do it.” The second was that designing and building cars was the easy part. The real challenge was finding the money to get projects off the ground.

Soft-spoken, voluble, and so discursive that even his tangents have tangents, Wiegert wasn’t a stereotypical promoter with a hard sell for every occasion. But he was so passionate and confident that he would pitch anybody and everybody in his search for funding. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that he’d amassed enough seed money to form a company, Vector Car, and build a running prototype. Named the W2, for “Wiegert twin turbo,” the car was on the cover of Car and Driver in December 1980, accompanied by a sexy model (who would later marry Wiegert).

The story, by staffer Larry Griffin, was an over-the-top paean to Wiegert’s creation. “What he wants to do is execute a flag-waving triple Immelmann and rocket-run right through the ranks of Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati, Aston Martin, and BMW. Shoot the suckers down, and you can plant the Stars and Stripes atop the smoldering heap,” Griffin wrote. “Our own Patrick Bedard describes the Porsche 928 as the triple distillation of evil, but compared with the Vector, a 928 is a Pacer in drag.”

Nearly four decades later, it’s hard to appreciate the impact the Vector had on enthusiasts suffering through one of the dullest eras in automotive history. Wil Wengert, a Beverly Hills entrepreneur who would later own two Vectors, remembers walking into a nondescript bar in a small city in China and seeing a poster of the W8 on the wall. These days, the notion of a fighter jet for the street seems like a cliché. But when the Vector was being developed, even the most exotic sports cars still featured welded steel frames, steel or aluminum bodies, engines that generated less than 400 horsepower, and analog everything. Vector pioneered the use of aerospace technology in a road car, including switchgear from an F/A-18 fighter, electroluminescent gauges, aviation circuit breakers, a honeycomb aluminum floorpan, and aircraft-quality fittings. Even today, Wiegert has no respect for the cars that were the Vector’s rivals. He dismisses the F40 as “a 308 with IMSA fender flares and twin turbos.” The Countach? “It’s a garage queen. You don’t want to drive it. The ergonomics are horrible. It always looked like a kit car to me.” As for the Porsche 959: “It didn’t impress me. The 912 I drove across the United States in 1968 looked almost like a 959.”

Besides putting Vector on the map, the Car and Driver story inspired a young engineer to visit the Vector shop, then in seaside Venice, California. Almost as soon as David Kostka met Wiegert, he went to work for him, first on a moonlighting basis, then clocking 100-hour weeks as chief engineer, production manager, and, ultimately, vice president of engineering. “This was a chance to make automotive history,” Kostka says. “It wouldn’t have happened without Jerry. The guy is so driven. There were so many times when anybody else would have given up. But he kept going and going and going. And I hung with him.”

Wiegert spent most of the 1980s seeking investors who were gun-shy about automotive startups after Bricklin and DeLorean crashed and burned. He put nearly 200,000 miles on the single W2. “Jerry was relentless about going to car shows,” Kostka recalls, “and we were too poor to trailer it there.” The Vector generated oodles of publicity, and Wiegert made the most of it, partying with Jerry Buss and Donald Sterling, owners of L.A.’s two NBA teams, lunching with Raquel Welch in the back seat of a Rolls-Royce, spending a night cruising around L.A. with a manic Robin Williams. He advertised, he promoted, he generated elaborate business plans, he distributed a brochure describing the Vector as “the world’s fastest investment.” Several deals came together only to fall apart at the 11th hour. With funding mostly from individual investors and a hefty settlement with Goodyear, which he sued for dubbing its new tire Vector, he raised millions of dollars, but there was never quite enough to go into production.

Magazines were full of glowing references to the Vector, but among the enthusiast press, the car’s long gestation period led to skepticism. In March 1987, AutoWeek ran a cover story under the devastating headline “The Great Vector Myth: At age 15, this would-be American supercar is still a long way from production,” in which writer Dutch Mandel likened the Vector factory to Neverland in Peter Pan and Wiegert to showman P.T. Barnum. The story remains an open wound, and Wiegert can’t talk about “that asshole article” without getting worked up. He filed a libel suit, but it fizzled. Adding injury to insult, financial setbacks forced Wiegert to dissolve Vector Car.

But like the creature in a Saturday afternoon horror movie, Wiegert refused to die. The next year, against all odds, he put together a public offering that grossed $6 million. The terms allowed Wiegert’s new venture, Vector Aeromotive Corporation, to issue warrants that garnered an additional $8.2 million. Eventually, Wiegert had 150 employees in 80,000 square feet of facilities in Wilmington, an industrial port city south of Los Angeles. And at the tail end of 1990, Vector proudly unveiled its first production vehicle, now known as the W8 Twin-Turbo.

The new car was more than a pretty face. Underneath the dramatic wedge-shaped body was a 6.0-liter aluminum Rodeck V-8 block, or the basis of a slightly shrunken fuelie drag motor, capped by two-valve Air Flow Research heads. Shaver Specialties, a top sprint-car motor builder, assembled the engines using a laundry list of contemporary racer parts, including forged TRW pistons, a forged crank, Carrillo stainless steel rods, roller rocker arms, and a dry-sump oiling system.

Augmented by a pair of Garrett AiResearch turbos, the engine dynoed at 625 horsepower on pump gas, or 730 horses after twisting the cockpit-mounted boost knob. (At night, drivers could see the turbos glowing red in their rearview mirrors.) The seats were from Recaro, the four-piston brakes from Alcon, the massive hub carriers from NASCAR.

Naysayers carped about the ancient GM Turbo-Hydramatic 425 three-speed slushbox, originally developed for the 1960s front-drive Oldsmobile Toronado and Buick Riviera. As in those cars, the transmission sat alongside the engine, motorcycle and Lamborghini Miura style, so there was no center console. But only the Hydramatic case was original; every other piece was custom-made and beefed up to handle the greater power. Plus, the transmission was fitted with a slick ratcheting mechanism that allowed clutchless shifting—standard practice in modern supercars.

The rich and famous lined up to buy the Vector. The first two W8s went to sheikhs in the royal family of Saudi Arabia. Other buyers included megadealer and exotic-car maven Ron Tonkin and Fredy Lienhard, a noteworthy sports car racer who owned the high-end Lista workshop storage system company. Publishing tycoon Malcolm Forbes flew to L.A. in his private 727, with “Capitalist Tool” emblazoned on the tail section, to spend a day with Wiegert and place an order for the last W8. But Andre Agassi, the long-haired tennis sensation, was the most famous—and infamous—buyer. Agassi wrote a $400,000 check for a W8 even before it was certified. After a test drive near his Las Vegas home, he returned the car and demanded a refund because the exhaust heat had melted the trunk carpet, his brother Phillip telling a reporter the car was “basically a death trap.”

On the other hand, John Paul DeJoria—cofounder of the Paul Mitchell hair products empire and the Patrón Spirits Company and current sponsor of the Tequila Patrón racing program—liked his car so much that he still owns it. “I bought a Vector because it was the coolest- looking car of the day,” he says. “The W8 should be remembered as one of the greatest cars ever made.”

One of the biggest selling points of the Vector was a top speed variously reported as 218 or 242 mph at a time when the 200-mph barrier had yet to be breached by a production car. The fastest speed was a self-reported 193 mph at Riverside International Raceway. As for the more outlandish claims, former Car and Driver editor-in-chief Csaba Csere says, “The only way it could have gone 241 mph was if you’d dropped it out of a 747 at high altitude.”

Although a lot of stories were written based on brief road drives of the W8, Car and Driver and Road & Track were the only magazines permitted to conduct instrumented tests. Despite various hiccups and less-than-ideal conditions, the numbers were legitimately show stopping for the day and easily dusted the competition: 0 to 60 mph in 3.8 seconds and the quarter-mile in 12.0 seconds at 118 mph in Car and Driver; 4.2 seconds and 12.0 seconds at 124 mph in Road & Track. R&T also saw 0.97 g in its skidpad test, the highest figure the magazine had ever recorded for a street car.

Doug Kott, who wrote the Road & Track feature story, recalls meeting Wiegert in Wilmington. “He sat me down with a video of the Vector and the stealth fighter,” he says. “Then he walked me through the shop. He loved to pick up a piece out of a bin and say, ‘You can see the mil-spec coding on the side.’ ” His most vivid memory of Kott’s stint behind the wheel was the unrivaled grunt of the twin-turbo motor. “It had a lot of lag, and it took a while to make boost,” he says, “and then, suddenly, it felt as if you’d hit hyperspace.”

Car and Driver gave the car mixed reviews after attempts to test the W8 devolved into a fiasco. The transmission failed after one car finished making passes for a photographer, and the engine in another overheated not once, not twice, but four times during abortive test runs. Kostka pulled an all-nighter so Csere could drag himself out of a hotel bed in a last-ditch effort to get some hard numbers. Csere managed a few decent passes at three in the morning on a deserted boulevard near LAX, but even then, the transmission was acting up. Looking back on the experience, Csere consigns the Vector to the purgatory reserved for ultra-high-performance, ultra-low-production cars that aren’t quite ready for prime time.

“Wiegert was a gifted stylist, but he had no production experience,” Csere says. “He wasn’t an engineer. He wasn’t a mechanic. He wasn’t a former race car driver. He seemed to think a car was a collection of premium components, and everywhere you looked were premium components. But he didn’t understand how to integrate and develop them. Wiegert told me I could drive the car across the country when I couldn’t even drive it across Los Angeles.”

To be fair, Csere tested the pre-production prototypes, and build quality improved once cars started being delivered to customers. Wil Wengert has owned two W8s, and he was about to buy a third when it was sold out from under him. “I drove them a lot,” he recalls. “The Vector was a perfect blend of muscle car and exotic car. It was built to be bulletproof. I drove the cars around Beverly Hills and all over Southern California and ran the hell out of them. If I’d tried doing that with my Lamborghini, I would have been looking at a $6000 clutch job after every weekend.”

Thanks to Kostka’s efforts, build time for the W8 dropped from 5500 worker-hours to 3500. Even so, by 1992, the base price had risen to $450,000, yet the company continued to hemorrhage money. In Italy, Bugatti reportedly burned through hundreds of millions of dollars to develop the EB110. Closer to home, it cost Dodge $70 million to bring the Viper to market, and as Kostka points out, “They were able to raid the Chrysler parts bin for things like door handles and switches.” Wiegert’s all-in expenditures were less than $35 million to create a factory and production infrastructure and then build 23 cars from scratch. “We were always undercapitalized,” Wiegert says. “I was able to do it because I knew how to get $10 worth of value out of a dollar spent.”

Wiegert began exploring new options to enhance the bottom line. He structured a deal to buy Lamborghini from Chrysler. He also decided to end production of the W8 and focus on an updated model with a more rounded body. Dubbed the Avtech WX3, the car featured a four- cam, four-valve Hans Hermann–designed turbocharged V-8 that developed 1200 horsepower (when the troublesome timing belt wasn’t slipping, causing a catastrophic meeting of valves and pistons). A coupe and a roadster wowed the crowd at the Geneva auto show in 1993.

But getting the Avtech into production was going to take money, and money was the one asset Wiegert didn’t have. When a group of Indonesian investors wined and dined him while promising to provide the capital he needed to put Vector in the black, Wiegert allowed them to buy into the company. He now concedes this was his biggest mistake. The problem wasn’t the investors’ resources; it was the investors themselves.

I have to confess that, by the time Wiegert gets to the Indonesians, the Vector story is starting to sound like one of those Netflix original series with lots of unbelievable drama and no ending. But truth, it turns out, is stranger than fiction. One of the principal investors was an American-educated businessman who also happened to be among Asia’s premier metal guitarists. The other was Hutomo Mandala Putra, better known as Tommy Suharto, the favorite son of Indonesia’s notoriously ruthless and corrupt dictator. An internationally renowned playboy, Suharto was enmeshed in numerous dealings of dubious legality. His extensive Wikipedia page has entries for “Business and nepotism,” “Bali land scandal,” “Explosives and bombings,” and “Rolls-Royce bribery case,” among other improprieties. He would eventually be convicted of murdering the judge who’d found him guilty of a multimillion-dollar real estate scam.

Wiegert is convinced the Indonesians plotted from the start to grab control of Vector. Through a front company called Megatech, they pumped a few million dollars into Vector to increase production. After commitments were made, the spigot dried up, and Wiegert was forced to lay off employees and default on payments to suppliers. Along the way, the Indonesians snaked the Lamborghini deal away from him. By March 1993, the situation was so dire that members of Vector’s board of directors voted to fire Wiegert. (He claimed two of them had been bribed by the Indonesians.) When the board fired him, Wiegert hired armed guards, changed the locks of the factory, and barricaded himself inside, prompting comparisons with David Koresh and the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas.

Dueling lawsuits were filed. Wiegert lost, at least initially, and what remained of the company moved to Florida, where a new car, the Vector M12, was designed and built. Despite the name, Wiegert and Kostka agree there was no Vector in the M12, which rejected the all-American, aerospace-inspired ethos of the W8 and was instead based on the Lamborghini Diablo. In a cruel and crowning irony, the car was powered by a longitudinal Lamborghini V-12, which was like allowing Aaron Burr to deliver the eulogy at Alexander Hamilton’s funeral.

Despite plans to build almost 100 cars the first year, only 14 production M12s emerged before the plug was pulled. Wiegert had the last laugh in 1999 when a court judgment returned control of the Vector name and the company’s remaining assets to him. But it was a Pyrrhic victory. Wiegert shut down the firm because, as he puts it, “it was radioactive, and I figured it was better to let it go and start a new company.” He then spent several years working to get a personal watercraft called the Aquajet Jetbike into production. He recently revived his plans to build a next-generation Vector, and he’s once again furiously working the phone and beating the bushes in his never-ending quest for investors.

Wiegert describes his hypercar-to-be as the 3-3-3 concept—3000 horsepower, 300 miles per hour, and a $3 million price. He’s coy about details, and I’m less interested in what the new car will be than in why he’s so determined to build it. He’s devoted most of his adult life to the Vector. The prospects for an automotive start-up are, if anything, even bleaker today than they were a generation ago. Wiegert has been out of the loop for nearly two decades. Ultra-sophisticated hybrid systems and chassis controls have become mandatory equipment. The Vector seems like ancient history. But Wiegert is implacably optimistic. “I’m in the wealthiest country in the world, and there are tens of thousands of guys who could put the Vector on the map,” he says, then flashes a disarming smile. “Everybody deserves a second chance,” he adds. “I haven’t had mine yet.”

Later, Wiegert is driving briskly up the Harbor Freeway in Los Angeles in his Mercedes-AMG CLS63 on his way to show me two Vectors owned by a Scandinavian collector. One, sans engine and instrument panel, sits in the shop in Harbor City where Kostka stores his vintage motorcycles. The other, attached to a trickle charger, lives in a warehouse across the street. Wiegert pulls off the cover to reveal the last of the production W8s, painted a show-stopping shade of iridescent green. “This was Malcolm Forbes’ car,” he says. “Most of the cars were graphite gray because that was the military look I wanted. But he wanted green, so I designed the color. I’ve never seen a green like this before.”

Like the color, the car is stunning—low, chiseled, mean, and purposeful. The wide rear end, with its horizontal row of taillights and twin-element rear wing, emphasizes the bulk and power of the transverse-mounted V-8. Seven distinct shapes conjoin to form the panoramic windshield. The high nose and the sharp creases, tracing an unbroken line that cuts through the side windows, represent aerodynamic thinking from an era before front splitters and rear diffusers. Despite the dated touches, the car manages to look modern. “It’s a unique, exciting shape with a bit of aircraft influence,” says Stewart Reed, chair of the transportation design department at ArtCenter, who saw sketches of the original Vector when he and Wiegert were students there. “The solid fuselage with side windows as perforations is a form that’s always going to look exotic.”

Wiegert swings open the door so I can see the digital instrument panel and luxurious cockpit. Then he insists I slither underneath the car to get a look at the impeccably finished de Dion rear end. The engine bay, housing a massive motor, twin turbos, and an aluminum intercooler, bristles with polished metal and anodized fittings. “It was built to last,” he says, “easy to service and maintain. It’s more sophisticated than the McLaren F1, with those kid seats on the side, which is just stupid. And it had the potential to go 230, 240, 250 miles per hour. It could have done 150 in the quarter-mile with a bit of tuner activity.”

Wiegert breaks away to take a call on his cell phone from somebody who might be able to deliver an investor willing to help finance an all-new Vector built around an engine milled out of billet aluminum. Wiegert patches another potential player into the conversation. The call goes on for 10, 15, 20 minutes. I’m running late for an appointment and eager to get going. But when Wiegert gets off the phone, he wants me to hear the engine running. I’m antsy, but he insists. After several delays, he’s finally seated in the cockpit. He cranks the ignition. Nothing happens.

It seems that if Wiegert didn’t have bad luck, he wouldn’t have any luck at all. “He deserves better than what the world has given him,” says former Road & Track editor John Dinkel, who has observed the arc of Wiegert’s career. Despite setbacks that would have crushed a lesser man, Wiegert carries on, scaling obstacles like a tireless and indomitable mountain climber. If he’s to be judged, it ought to be on his accomplishments, not his failures. History will show that he created the world’s first true supercar. From the ground up. Based on a singularly personal vision and largely thanks to his own heroic efforts.

Today, Wiegert is starting at ground zero as he embarks on what seems like an impossible quest to raise money for a new-and-improved Vector. I can’t help wondering if he has any regrets. He could have undertaken a less ambitious project, or allied himself with a large corporation that could have properly financed development and production. He could have cut his losses and bailed long ago. Knowing then what he knows now, would he have done things differently? He repeatedly sidesteps the question, and when he finally answers it, his reply is oblique.

“I would like this story to be a lesson about how difficult it is to achieve our dreams,” he says. “I would like it to express the difficulties of staying on course and tackling roadblocks that would have caused most people to divert course or give up. I never felt like I just wanted to say, ‘F*ck it.’ Never. I just did it.”