Media | Articles

Love Smokey and the Bandit? Hooper is a must-see

A bar fight with Terry Bradshaw, a chariot race, backwards driving down the highway, a helicopter stunt without a parachute, a beer-drinking horse, and an impossible jump across a 325-foot gorge. This is Hooper, Hal Needham’s second film in a six-movie run with Burt Reynolds—semi-autobiographical, a tribute to stuntmen by stuntmen.

Reynolds plays Sonny Hooper, the Greatest Stuntman Alive, who’s currently working on Roger Deal’s The Spy Who Laughed At Danger as its stunt coordinator and Adam West’s stunt double. It’s an aimless, eccentric character study, elevated by its characters’ charm and the sheer pleasure of watching Burt Reynolds raise hell.

Stunt work isn’t just a job, it’s a way of life, but stuntmen are constantly being supplanted by younger, better stuntmen who are not yet afflicted with chronic pain or an awareness of their mortality. Hooper’s already unseated his girlfriend’s father, Jocko Doyle (Brian Keith), and now the new kid in town, Jan-Michael Vincent’s Delmore “Ski” Chinski, threatens to usurp Hooper. Jocko believes the old guys do it for the good times and the “nice memories—what the hell else is there?” But the young guys are another breed entirely; they do it to “prove certain things can be done, that a man can do just about anything he puts his mind to,” according to Ski. Hooper laments that this new generation is younger, stronger, tougher, don’t take pills or drink, and “they use little pocket calculators.” To them, stunt work is a science, not an art.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Hooper is about the fun of making a movie, but it’s also about the toll it takes on stuntmen. Hooper casually says, “I’ve seen my X-rays, they look like a map of L.A.” His life is full of ominous doctor’s appointments, Percocet popping, lidocaine injections, and booze. His doctor tells him, “The odds are against you. If you were a horse, I’d shoot you.” Hooper must decide whether to keep on doing the job that he loves until he’s paralyzed or dead, or to go against his nature—and save his hide—by finally settling down with his girlfriend, Gwen (Sally Field), on their ranch.

Hooper’s decision is complicated by The Spy Who Laughed At Danger’s director, Roger Deal (Robert Klein), a self-important idiot who says things like, “Films are tiny pieces of time… and we captured it,” or when they’re setting up the film’s earthquake scene: “It has a nice grayness, like La Strada.” Deal pressures Hooper and Ski into doing the film’s final stunt, valuing his production above the lives of his stuntmen, because the gorge jump is “the statement [he wants] to make.” No one ever won an Oscar for second best, Deal claims, as if his film could be a contender for that particular honor. Hooper’s solution is a kind of compromise: He’ll do one last hair-singeing stunt for $100,000. And then, he’ll quit.

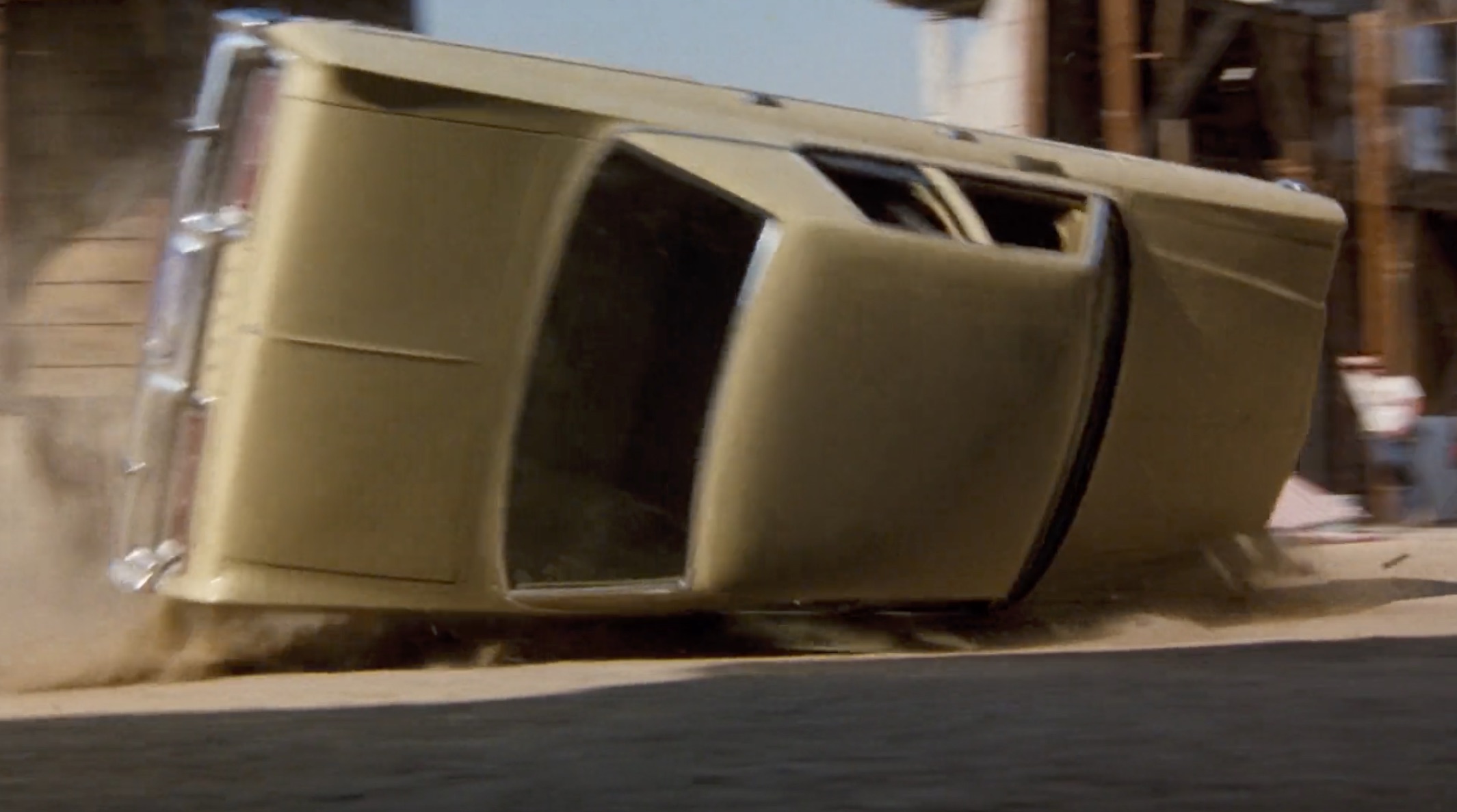

Hooper featured two iconic vehicles, The Spy Who Laughed at Danger’s hero car, a Mayan Red 1978 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am with a rocket booster in lieu of a backseat, and Hooper’s own truck, a red 1978 GMC 4×4 K15 stepside squarebody pickup, modified with KC lights, a chrome roll bar, a bed cover, custom pinstriping, and parts from Dick Cepek. Hooper drives it backwards going 55 mph on the Pacific Coast Highway so Jocko can grab a beer from the people riding alongside them. Hooper gets pulled over for “unsafe backing,” but with the help of his friends, he discreetly hooks the cop’s belt to a wire attached to a utility pole, and the cop flies off his motorcycle as Hooper and company speed away.

The Trans Am is the star of the film’s climax, its most famous scene, one of the greatest stunts of all time: a jump across a 325-foot gorge. Some believe that the stunt was faked, but Needham once told NPR’s Terry Gross that he hated faking stunts. “A guy jumps off a 250-foot dam, and it cuts to the water and he bobs up, like he’s a duck. And you go, ‘Wait a minute. Give me a break. A guy would kill himself doing that. There’s no way he could do it.’ To me, it takes all of the reality out of the show. I just can’t stand it. Even as a director, I never did that stuff. We did it for real.”

Needham himself suffered a broken back (for the second time) jumping a 140-foot canal in a rocket-powered pickup for GMC. But it was Buddy Joe Hooker who made that 325-foot jump for real, setting a record for rocket-assisted stunts. Thankfully, the car that was sacrificed in the jump was a retired drag car, not the Trans Am (though after promoting the film at Chicago and Miami auto shows, the T/A vanished).

Hooper’s and Ski’s rocket-fueled flight over the abyss is the baroque version of the infamous Smokey and the Bandit leap over the Mulberry Bridge that Needham and Reynolds pulled off the year before. Meaningfully, the stunt must be performed by two men—neither Hooper nor Ski can do it alone, and it’ll take the best of both them to succeed. Ski drives as Hooper navigates and monitors their equipment. The town crumbles around them as “the biggest earthquake ever” hits, buildings explode, cars and motorcycles crash, smokestacks collapse. The bridge blows, Ski balks and brakes at the final moment, insisting that they don’t have enough pressure. It’s Hooper who says they have to do it—Ski finally, giddily agrees—and the rocket-powered Trans Am flies across the abyss, and lands more or less intact on the opposite bank.

But the film’s most satisfying stunt might just be its simplest. Once Hooper and Ski wrap up the world’s greatest stunt, the director finally apologizes to Hooper for being a tyrannical egomaniac, and waits for him to accept. Instead, Hooper punches him in the face, takes a bow, and smiles wide at the camera.